When Poor People Vote

Bernie Sanders is right that many of the poor don’t vote. But the Left can’t win without them.

Last week, Bernie Sanders made a seemingly uncontroversial comment about the intersection of class and voting, and the punditocracy exploded with derision and contempt.

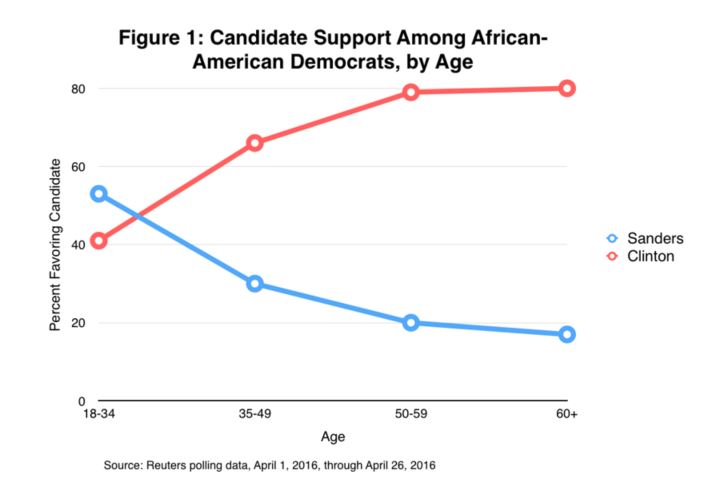

It all started with an NPR post commenting on the seeming oddity of Hillary Clinton, not Sanders, winning most of the states with the highest levels of income inequality. “[T]his doesn’t necessarily mean that Clinton is beating Sanders at appealing to voters on the basis of inequality,” the report acknowledged, noting that Clinton’s dominance in the high-inequality South — driven by her overwhelming support from older African Americans (see Figure 1) — likely explained the correlation.

Several days later, however, NBC’s Chuck Todd confronted Sanders on Meet the Press with NPR’s “interesting numbers” and asked the Vermont senator to speculate about why he was losing high-inequality states.

Sanders was blunt. “Well, because poor people don’t vote,” he replied. “I mean, that’s just a fact. That’s a sad reality of American society. And that’s what we have to transform. We have … one of the lowest voter turnouts of any major country on Earth. We have done a good job bringing young people in. I think we have had some success with lower-income people. But in America today — the last election in 2014, 80 percent of poor people did not vote.”

The commentariat pounced. “It’s not clear that larger turnout among poor voters would have actually helped Sanders against Clinton,” John Wagner and Anne Gearan wrote in the Washington Post. “Sanders has lost Democratic voters with household incomes below $50,000 by 55 percent to 44 percent to Clinton across primaries where network exit polls have been conducted.” Everywhere from the New York Post to New York magazine to the Huffington Post to Reason magazine to Vox echoed the Washington Post.

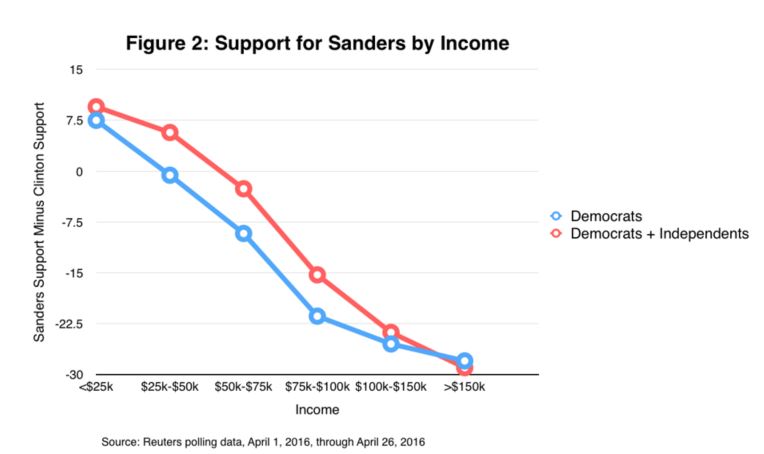

But however widespread, the alleged debunking betrayed a lack of understanding of polling data. By definition, the exit polls used by the Washington Post and others only measure voters. Sanders was talking about non-voters. When both voters and non-voters are included — as Reuters surveys from the past month do (displayed in Figure 2) — Sanders’s understanding of his support is undoubtedly correct. Whether it’s solely Democrats or both Democrats and independents, the lower one’s income, the more inclined he or she is to support Sanders.

Sanders’s margin of support among low-income Americans is all the more striking given Clinton’s strength among African Americans, who are more likely than whites to be poor. (Sanders’s well-documented support among millennials — who are likely to be low-income because of their age and the awful job market they’ve entered — probably accounts for some, though not all, of his edge with poor Americans writ large.)

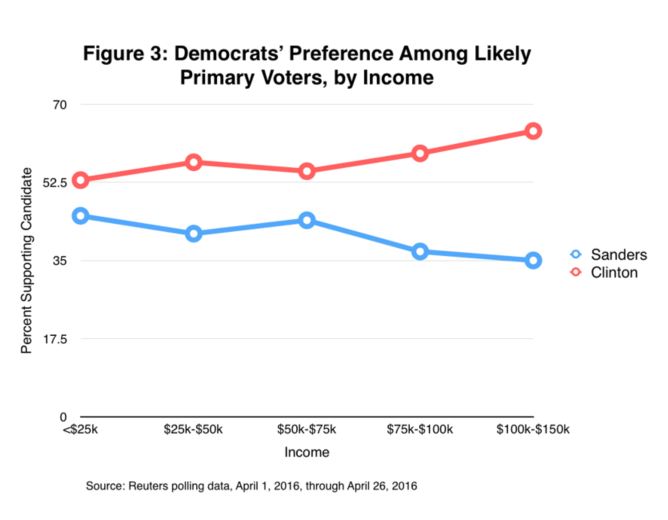

Keeping with Sanders’s assertion about his social base, it’s also clear that poor people casting a ballot in the primary have different opinions from those who aren’t. Among Democrats who plan to vote in the Democratic contest, every income group favors Hillary Clinton (see Figure 3). It’s apparent that, to Sanders’s detriment, the low-income Americans that favor him tend not to vote.

Neither Sanders’s strength among poor Americans nor the divide in candidate preferences between voters and non-voters should come as a surprise. The poor tend to be more supportive than the rich of the type of spending and income redistribution Sanders advocates. Demographically, non-voters are “younger, more racially diverse, [and] more financially strapped” than the electorate, as a recent Pew study put it.

Moreover, as Demos’s Sean McElwee has repeatedly demonstrated, compared to a wide range of voters, non-voters have decidedly more favorable views toward pro-worker policies like paid sick leave, free community college, a financial transactions tax, and aid to the poor.

Without the participation of the low-income non-voters Sanders referenced, the type of social-democratic politics he advocates, let alone something more radical, is doomed. In that sense, Sanders’s conception of a democratic political “revolution” made possible by luring habitual non-voters to the polls with the promise of progressive policy is accurate. His problem has been execution, not vision.

Poor non-voters do support Sanders and his social-democratic platform. Sanders’s campaign just hasn’t been able to sufficiently mobilize non-voters, or reach other portions of the electorate generally sympathetic to his policies, especially African Americans.

What are the issues?

For decades, political scientists insisted that non-voting was a sign of satisfaction with the status quo, the “politics of happiness.” This sanguine view always had one nagging problem, though. As sociologists Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward wrote in Why Americans Still Don’t Vote, “no one has offered an adequate explanation of why this ‘politics of happiness’ is consistently concentrated among the least well-off.” They blamed barriers to voting and the United States’s two-party system for low turnout among the poor.

Piven and Cloward, believing that getting the poor to vote was key to both fending off attempts to cut social spending and pursuing social-democratic goals, threw themselves into organizing around expanding voter access. Their work culminated in the passage of the National Voter Registration Act in 1993 (commonly known as the “Motor Voter Act”).

Yet they knew such reforms wouldn’t prompt low-income people to go to the polls if they saw a growing “gap between the issues Americans say are important and the national legislative agenda.” And that’s exactly what’s happened.

As a bevy of recent research has shown, policymakers listen to the views of upper-income Americans, rather than those of poor or even middle-income people. When non-voters look at American politics, they’re unlikely to see politicians meaningfully addressing their concerns.

In contrast to other democratic countries, where citizens at least have multiple parties to choose from, all that’s on offer in the US is two parties unconcerned with the views of low-income people.

As one recent study found, the poor see few differences between the parties and “are precisely the ones least likely to see the candidates as offering meaningful choices on issues” — especially ones regarding income redistribution. As a result, these non-voters — who are already often too busy or too stressed to make time to vote — become cynical and discouraged.

Lack of organization among the poorest Americans reinforces and augments the power of business, locking in a vicious cycle in which low turnout makes politicians even less attentive to poor people’s concerns — leading to even more apathy toward the ballot box.

The only hope for a viable left politics in the United States is to succeed where Sanders has come up short. The structural obstacles to progressive reform under capitalism are already considerable. But international comparisons demonstrate that low voter turnout, especially among the poor, makes it almost impossible to enact the type of tax and spending programs necessary to curb inequality and end poverty. As the Right tries to make it more difficult to exercise the franchise, one of the Left’s tasks is to make voting easier.

Lowering barriers isn’t enough, however. Discouraged non-voters need to see their economic views reflected in politics. People need a reason to show up to the polls. “[Sanders is] not moving a party to the left,” as one pollster put it. “He’s moving a generation [millennials] to the left.” But unless left-leaning activists can build power inside and outside that party, millennials will become just another group of left-leaning non-voters.

Ultimately, Bernie Sanders was right when he said his campaign suffered because “poor people don’t vote.” One of the best ways to make the revolution he’s called for a reality is to change that.