To Emulate Zohran, Rebuild Left Institutions

Zohran Mamdani’s win in New York has inspired the Left far beyond the city. But in Canada, as elsewhere, trying to replicate his style without rebuilding the institutions and political cadre that made it possible is a dead end.

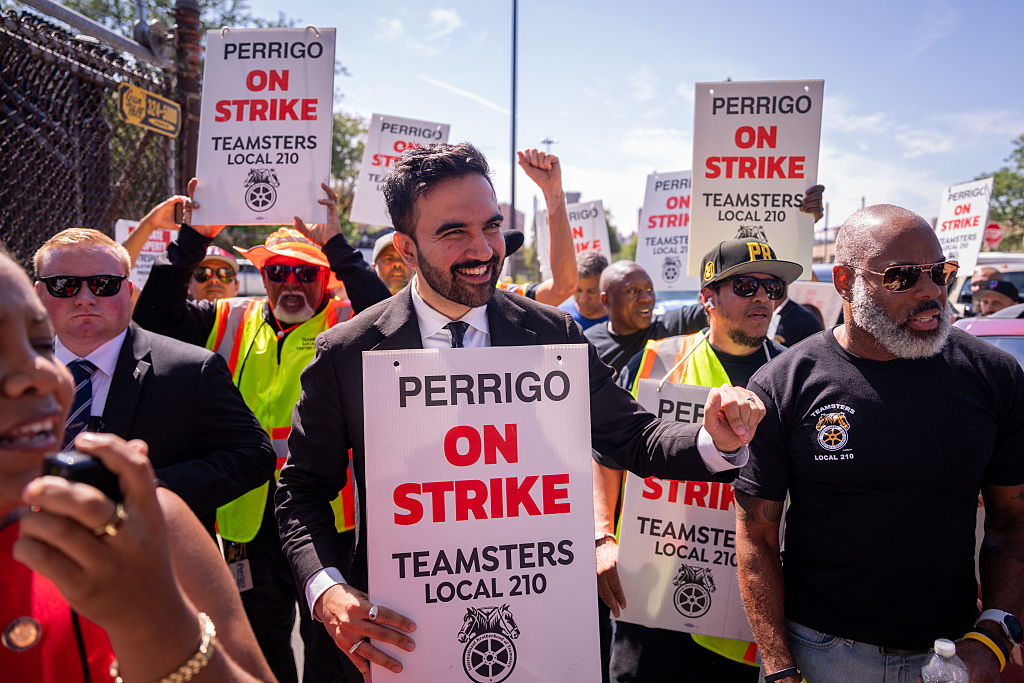

Until Canadian socialists commit to building something of our own, no moment similar to Zohran Mamdani’s in New York City will arrive. (Adam Gray / AFP via Getty Images)

When New York State Assemblyman Zohran Mamdani announced his run for mayor of New York City, few in Canada were likely paying attention. But in the wake of Mamdani’s inspiring win, the Canadian chattering class, from the pundits to political candidates across the political spectrum, have decided that Canada needs a “Mamdani moment.”

Every pundit, Twitter user, and left-wing politician in the country seemed to have a take on how the Canadian left could take advantage of Mamdani’s win. If the Left played its cards right, they argued — if it embraced videos of candidates walking and talking in urban settings, copied his ground game, adopted bold ideas, or, most simplistically, called itself democratic socialist — then maybe, just maybe, Canada could have its own “Mamdani moment.”

Comparison is natural, and failing to learn from Mamdani and the New York City left would be a mistake. But so far, the lessons drawn appear to stop at digital tools and communications strategies featuring stylized text and quick-cut videos of candidates speaking directly to the camera as they stroll through their communities.

It doesn’t work like that.

Canadian socialists can and should study Mamdani’s victory. But not as a template to be copied wholesale. It’s time to start searching for our “moment” at home. That means building a genuinely homegrown, authentic left-wing ecosystem in Canada and fighting for a truly local vision of Canadian socialist politics — a lesson that applies just as much to socialists elsewhere, even if the Left in some of those countries, now also looking to the “Mamdani moment,” is not as sclerotic as in Canada.

EDA Dysfunction

Antonio Gramsci describes a war of position as a long-term effort to create counterhegemonic culture, organic intellectuals, and class consciousness. In many ways, Mamdani’s victory in New York City represents a win in precisely this kind of war of position, one that the Left and New York City Democratic Socialists of America (NYC-DSA) have been waging for more than a decade. By contrast, it is a fight that the Canadian left in Canada has failed to engage in.

Where NYC-DSA and the broader DSA have cultivated a lively internal culture, actively developing social and political cadre through sports leagues, choirs, and a mix of electoral, union, and movement organizing, focusing on establishing durable local institutions, the New Democratic Party (NDP) and the Canadian left have largely abandoned this dimension of politics. One of the key reasons the Canadian left has been unable to win is a lack of robust left-wing institutions.

The principal organizing unit of the NDP, electoral district associations (EDAs) — roughly akin to DSA chapters — are, in many cases, moribund. Beyond fundraising, summer BBQs, and Christmas parties, most EDAs do little outside of election season. Even the largest EDAs have done little to establish themselves as homes for the local left. The Left in Canada is disjointed. By contrast, DSA chapters have become genuine local institutions, places for movement and electoral organizers to mix, collaborate, and learn. Theoretically, NDP EDAs should serve this function; in practice, they are often populated almost exclusively with party functionaries. The NDP and left movement organizing often exist in a tense, if not mutually skeptical, case-by-case alliance.

The problem isn’t that the Canadian left lacks a concrete political home, exactly — the NDP, as a formal political party, provides one. Rather, it’s that this home has become thin, procedural, and almost entirely electoral in character. It does very little to develop cadre, sustain political education, or reproduce a vibrant left culture outside of election cycles.

DSA, meanwhile, has worked to build energy, commitment, and shared political life. This allows for the creation of spaces where members are socialized into politics, develop skills, and come to see themselves as part of a collective project. This is less a matter of organized form than it is function. Where the NDP is capable of offering structure, it often fails to create momentum; where DSA lacks formal party status, it compensates through networks of social and political engagement.

As a result, Canadian socialist politics remains institutionally present but culturally and organizationally underdeveloped. It needs sustained cadre development and a living political ecosystem around the party, otherwise it will remain incapable of waging the kind of war of positions necessary to build counterhegemonic power.

No Branch-Plant Socialism

There is an obvious irony in arguing that Canadian socialists should focus less on American politics in the pages of an American magazine — but, notwithstanding Jacobin’s commitment to internationalism and international coverage, that irony is itself part of the problem. I would hazard a guess that Jacobin is Canada’s most-read socialist publication. Even the most comparable institutions, like Broadbent Institute’s Perspectives Journal, Rabble.ca, and Briarpatch, have significantly less reach. The same is true of Canadian left think tanks, which wield significantly less influence than their American and Canadian conservative counterparts.

A study by Paul Saurette and Shane Gunster found that Conservative think tanks focus heavily on talent development and on redefining symbols of Canadian identity along conservative lines. Barring the work of the Broadbent Institute, Canadian left think tanks tend to focus narrowly on policy development, with limited reach or impact, and show little interest in defining broader cultural attitudes or national identity in left-wing terms.

Canadian socialists love to accuse Canadian conservatives of importing the American right’s playbook. While there is some truth to this charge, it ultimately falls flat. In truth, Conservatives have better understood this war of position in the Canadian context, generating a homegrown conservatism that learns from, and networks with, right-wing movements worldwide. Accounts like Canada Proud on Facebook reach millions of people in Canada every month, mixing far-right and conservative politics with clips of hockey games, wildlife, and Canadiana that resonate widely. The Right has also created venues for debate, policy development, and the cultivation of organic intellectuals through organizations like the Canada Strong and Free Network and a multitude of emerging papers and magazines. In comparison, the Canadian left remains institutionally weak and culturally hollow.

The real lessons to be drawn from Mamdani’s victory lie in the slow work of building organic socialist institutions, developing homegrown intellectuals, and embracing a mass party style of organizing. But these institutions cannot be carbon copies of their American counterparts. Embracing a homegrown socialism means creating institutions that fit into the Canadian ecosystem and respond to the traditions and realities of Canada’s left.

Local Vision

Mamdani is a uniquely New York candidate. His campaign logo evokes the look of an old New York shop sign; he produced a series of videos on New York socialist politicians; and he spoke fluently about local issues, from the transit system to building on Bill de Blasio’s childcare program. By contrast, Canadian socialist candidates are rarely uniquely local in the same sense. Canadian left policy issues should foreground Canadian conditions and priorities, not import debates and the framing of policy issues from the United States.

Canadian socialists should embrace what makes us Canadian as well as socialists. This doesn’t have to mean wrapping ourselves in the flag, but it does require taking our own political culture, institutions, and material realities seriously. It also means generating ideas with Canadian historical and cultural salience rather than reflexively following the lead of the Left in the United States. It is time for Canadian socialists to start shaping Canadian politics on their own terms.

Learning from Mamdani means understanding that emulating him and his campaign is not enough. His victory was not the product of a viral communications strategy, a clever brand, or a sudden ideological shift among voters. It was the result of years of deliberate, organized work to build left-wing institutions capable of producing candidates like him — and getting them across the finish line. Mamdani himself is also a rare, generational political talent. He is an unusually gifted communicator and coalition-builder. But such talents do not emerge in a vacuum. They are only made viable by robust organizational ecosystems. To treat his success as something that can be copied through aesthetics alone is to fundamentally misunderstand how political power is built.

Canadian socialists must engage in the arduous, boring, often invisible work of constructing a left political ecosystem capable of shaping consciousness, coordinating struggle, and embedding socialist politics into everyday life. Moments are made, not waited on. Without that foundation, any apparent breakthrough will be fleeting, shallow, and easily reversed.

This means shifting our focus away from quick electoral fixes and toward building the institutions that make electoral victories meaningful. It means rebuilding political homes where organizers, workers, tenants, students, and activists can encounter one another not only during campaigns but year-round. It means treating local organizations not as administrative shells or fundraising vehicles but as living sites of political education, culture, and collective identity.

But the project cannot succeed without confronting a deeper structural problem: the NDP’s long-standing reliance on the consulting class and what Alex Hochuli calls MANGOs — members of media, academia, arts, and NGOs — a professionalized stratum that has come to dominate NDP activism while disconnected, and sometimes hostile, to working-class life. Reanimating internal culture and cadre development is necessary, but it will fail if that cadre is drawn from the same professional, nonprofit-adjacent milieu that has dominated the party for years.

None of this is to suggest that DSA itself is a working-class organization. It is, in practice, largely a middle-class one, and its limits reflect this fact. The point is not that the DSA-as-model resolves the problem of class composition, but that it has nevertheless functioned as an institutional incubator. It has provided a space that is capable of providing political education, organizational experience, and coordination across movements.

If Canadian socialists cultivated such a space, we could take more seriously the war of position in our national context. Conservatives have understood that power is cultural as much as it is electoral, and they have invested accordingly, developing media ecosystems, intellectual networks, and narratives that speak to Canadian identity. A homegrown socialism must contest these spaces, articulating a vision of Canada that is egalitarian, collective, and rooted in shared material interests rather than abstract ideals.

Canada does not need a “Mamdani moment.” It needs the conditions that make such moments possible. The task ahead is not imitation but construction. And until Canadian socialists commit to building something of our own — durable, rooted, and unapologetically local — no moment, no matter how skillfully borrowed from elsewhere, will arrive here.