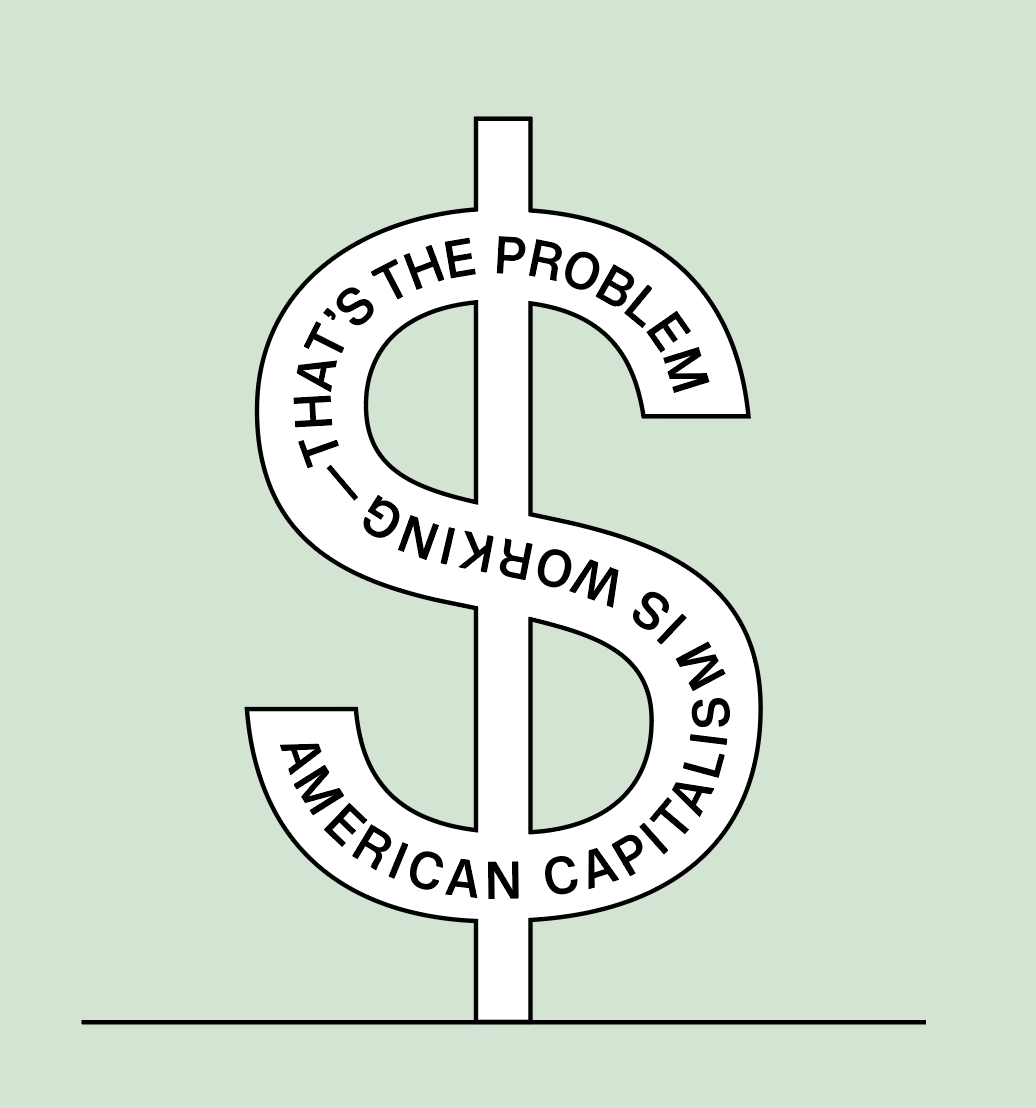

American Capitalism Is Working — That’s the Problem

The United States is not a failed state — just ask any American capitalist. But we desperately need something better for everyone else.

The United States is the richest, most powerful nation in the world. But these days, failure, not success, is the word most associated with it.

Writing in the Atlantic, George Packer said, “Every morning in the endless month of March, Americans woke up to find themselves citizens of a failed state.” Our national response to the coronavirus pandemic, Packer contended, has forced us to ask questions we’ve never before had to ask, such as, “Are we still capable of self-government?”

In an interview with Salon, economist Richard D. Wolff compared America to “a patient who has had a really bad cancer or a heart attack, and is now kept alive with tubes and chemicals and all the rest of it. He is not dead, but is in deep trouble.”

Tom Engelhardt even suggested in the Nation that we might need a new term for the contradiction that is America. The United States may be rich and powerful, he argued, but it “is also afloat in a sea of autocratic, climate-changing, economic, military, and police carnage that should qualify it as distinctly third world as well.” Perhaps “fourth world,” to capture the fact that we are “potentially the most powerful, wealthiest failed state on the planet.”

It certainly feels like we’re failing. What kind of state deploys the National Guard to menace peaceful protesters while elderly people are being decimated by COVID-19 and forest fires are raging? What kind of state forces its nurses and doctors to work without proper protective equipment? Or allows its people to go hungry and get evicted, while handing out trillions to the wealthiest few amid a nationwide crisis?

Americans are right to be furious at the Trump administration’s ineptitude and willingness to dump the costs of the coronavirus pandemic onto working people. But despite its obvious failures, the United States is not a failed state — and why this distinction matters goes beyond semantics. Diagnosis shapes response. If we’re going to get ourselves out of this mess, we need a clearer picture of what is broken and how to begin fixing it.

The Sum of All Failures

Even among the observers cited above, there is broad disagreement on the path that led the United States from capitalist success story to alleged basket case. Wolff thinks America has been a terminally ill patient since the postwar boom ended in the 1970s. Packer thinks America is in the midst of a cyclical “unwinding” punctuated by major crises. Engelhardt blames post–Cold War hubris.

There is remarkable agreement, however, on the end point — America as failed state. This consensus is a bit surprising, given the history of the term.

The term “failed state” came into use after the collapse of Somalia. In 1994, the CIA created the State Failure Task Force to work out the causes of state failure. A few years later, the Clinton administration declared a new foreign policy emphasis that advocated humanitarian, diplomatic, economic, military, and various other flavors of imperialist intervention to purportedly rescue and fix failed states.

Then 9/11 happened, pushing the issue of failed states into the mainstream. Afghanistan, designated a failed state under Taliban leadership, had harbored Al-Qaeda. Policymakers and elected officials warned that failed states were dangerous, that they created lawless playgrounds where terrorists and other ne’er-do-wells thrived. George W. Bush’s 2002 National Security Strategy announced that “America is now threatened less by conquering states than by failing states.” In his 2004 book State-Building, Francis Fukuyama deemed weak and failed states “the single most important problem for the international order.”

When did a state become a failed state? Harvard University’s Robert I. Rotberg offered a list of political goods that successful states provide their residents: security, an independent judiciary and a predictable system for adjudicating disputes, the ability to participate in the political system, medical and health care, schools and educational instruction, good infrastructure (physical, communications, commerce), a sound money and banking system, a free civil society and entrepreneurship opportunities, and environmental protection.

Failed states were states that couldn’t provide these political goods, that had become subsumed by violence, corruption, and dysfunction. Lists of countries, many of them former colonies, were produced (Angola, Burundi, Côte d’Ivoire, East Timor, Haiti, Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Sudan, to name a few) and held up as examples of “classical failed and collapsed states.” Restoring order in these broken states became a matter of national security; indeed, the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan were sold in part as state-building initiatives.

But as the first decade of the twenty-first century drew to a close, the concept lost its luster. It had become painfully obvious, after countless lives were destroyed and trillions of dollars wasted, that the United States wasn’t very good at state-building. Moreover, scholars decided that the term itself yielded little of theoretical value, reflecting, as Charles T. Call noted, “the schoolmarm’s scorecard according to linear index defined by a univocal Weberian endstate.” In his 2006 book Failed States, Noam Chomsky used the term as little more than a throwaway foil to point out that honest observers would have “little difficulty in finding the characteristics of ‘failed states’ right at home” in the United States.

So why is the term being revived today?

No doubt, things are bad in America. Income and wealth inequality have widened considerably over the past four decades, and many indicators show a deteriorating quality of life for poor and working-class people. The United States has dropped to the twenty-eighth position on the global Social Progress Index (down from nineteenth in 2011), and a Pew Research Center poll of how people in thirteen countries view America shows global regard for the stars and stripes at an all-time low. Much of the country’s infrastructure needs upgrading; housing and food insecurity is persistent; millions lack access to high-quality, affordable medical care; education has become more segregated and expensive; and police violence is a major problem. On top of all this, the country is being ravaged by a viral pandemic and its accompanying economic, social, and political fallout.

Nonetheless, the United States doesn’t fit the definition of a failed state as the term has traditionally been used. The dollar hasn’t become worthless paper, and the economy hasn’t collapsed. The country hasn’t split into clashing states ruled by warlords or been torn asunder by civil strife. Rule of law and the judiciary remain robust, and government institutions aren’t hobbled by corruption. Hospitals and schools function, for the most part. Planes fly, the lights turn on, the mail gets delivered, and highways are easily traversable.

Is the current popularity of the term simply a shorthand, used to underscore the ineptitude and inadequacy of the US government’s response to the coronavirus? Is it just an evocative label to signify the depths of our disgust for how low President Trump has brought us, to capture the taste of our collective despair as we try to imagine what the next four years hold?

Perhaps. But we should be cautious about throwing it around. Referring to America as a failed state can obscure both the nature of the crisis at hand and the demands democratic socialists should be making to get someplace better.

Great Success

Part of the confusion lies in how the role of the state is imagined in popular accounts. Rotberg, in delineating the rubric for a failed state, relied on a widely shared belief that “the responsibility of a nation-state [is] to maximize the well-being and personal prosperity of all of its citizens.” This isn’t wrong. States must ensure order and welfare, broadly speaking, in order to retain legitimacy. But in capitalism, a greater determination of legitimacy is how well the state protects and nurtures capital accumulation.

And in its role facilitating capital accumulation, the US state is a great success. Over the past half-century, it has proven itself quite nimble at creating the conditions for American corporations to thrive, both at home and abroad. Trade agreements, taxpayer-funded research, deregulation, sweetheart tax deals, and a wholesale attack on the social safety net and organized labor have revived the conditions for profit-making again and again.

At the same time, the US state and its elected officials have been willing and able partners for elites seeking to protect their interests. Like corporations, America’s millionaires and billionaires have enjoyed an open door to power, achieving tax breaks and many other benefits through legislation tailored precisely to the needs of the ruling class.

Even during the coronavirus pandemic, the US state has shown its mettle in protecting the interests of capital. The government made little effort to supply its health care workers with protective equipment, to establish a nationwide testing program, or to ensure access to health care, food, and housing for Americans impacted by the outbreak — but the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department deftly maneuvered to calm the markets, pumping trillions of dollars into Wall Street through bailouts, grants, and bond purchases, as well as promises to keep interest rates low indefinitely.

A Financial Times story illuminates the results of this maneuvering. Trading volumes in the spring were six times higher than normal, as global elites took advantage of surging stock prices. In Monaco, a popular coronavirus refuge, wealthy foreigners “spent much of their time frantically trading their portfolios.” “[W]e will have a very good year,” commented one private banker.

That the state failed to provide the same financial and social protection for working families, aside from a short-lived federal unemployment subsidy and an ill-conceived Paycheck Protection Program, was not a result of incapacity or generalized failure. It is the response of a state that has been fine-tuned to meet the needs of the country’s wealthiest citizens and corporations, and to ignore or minimize the needs of ordinary people. As Nicos Poulantzas argued long ago, the state is not a static or intrinsic entity; it’s a dynamic, historically grounded relationship of class forces.

If we see America as a failed state on the verge of disintegration, collapse, or slide into dictatorship, our policy goals will reflect that focus. If we accept that we live in a failed state, how do we go about fixing it?

We might, like Engelhardt and many others, view getting Trump out of office as the top priority. Or, like Packer, we might emphasize the need to take citizenship seriously and value solidarity. These are worthy goals. But, on the whole, fixing a failed state is a nebulous, often apolitical project.

In this moment, a clearer vision of renewal is both necessary and possible when we focus on who and what the US state directs its resources and energies toward, rather than whether or not it has lost its capacity to rule.

Framing the problem this way highlights the goals of democratization, decommodification, and redistribution. It underscores the need to build working-class institutions capable of transforming the state itself into an institution that works for ordinary people.

It is also a reminder that if we want a state that doesn’t fail us, we’ll have to fight for one.