Let Them Eat Profit

Governments have turned a blind eye to tax havens in order to protect corporate profitability.

Lynne Hand / Flickr

The leak of the so-called Panama Papers has certainly set the cat of popular disgust among the pigeons of the super-wealthy global elite. But, of course, pigeons can fly away.

The Panama Papers contain 11.5 million confidential documents that provide detailed information about more than 214,000 offshore companies listed by the Panamanian corporate service provider Mossack Fonseca, including the identities of shareholders and directors of the companies.

An anonymous source using the pseudonym “John Doe” made the documents available in batches to German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung beginning in early 2015. The information documents transactions as far back as the 1970s and eventually totaled 2.6 terabytes of data.

Given the scale of the leak, the newspaper enlisted the help of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which distributed the documents for investigation and analysis to some 400 journalists at 107 media organizations in 76 countries.

Law firms generally play a central role in offshore financial operations. Mossack Fonseca, the Panamanian law firm whose work product was leaked in the Panama Papers affair, is one of the biggest in the business. Its services to its clients include incorporating and operating shell companies in friendly jurisdictions on their behalf.

They can include creating complex shell-company structures that, while legal, also allow the firm’s clients to operate behind an often impenetrable wall of secrecy. The leaked papers detail some of their intricate, multi-level and multinational corporate structures.

Mossack Fonseca has acted on behalf of more than three hundred thousand companies, most of them registered in financial centers which are British Overseas Territories. The firm works with the world’s biggest financial institutions, including Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Société Générale, Credit Suisse, UBS, Commerzbank, and Nordea.

The documents show how wealthy individuals, including public officials, hide their money from public scrutiny. The papers identified five then–heads of state or government leaders from Argentina, Iceland, Saudi Arabia, Ukraine, and the United Arab Emirates; as well as government officials, close relatives, and close associates of various heads-of-government of more than forty other countries. The British Virgin Islands is home to half of the companies.

Reporters found that some of the shell companies may have been used for illegal purposes, including fraud, drug trafficking, and tax evasion. Igor Angelini, head of Europol’s Financial Intelligence Group, recently said that the shell companies used for this purpose also “play an important role in large-scale money laundering activities” and corruption: they are often a means to “transfer bribe money.”

The Tax Justice Network called Panama one of the oldest and best-known tax havens in the Americas, and “the recipient of drugs money from Latin America, plus ample other sources of dirty money from the US and elsewhere.”

The most shocking thing about the Panama Papers is not the likely criminality and drug laundering, but that it is legal. It is legal in most countries to set up an offshore account for a company or trust as long as the directors are not “resident” in the country where taxes should be paid. The company may be subject to local taxes but these are minimal or nonexistent.

So if you run a fund and it is registered in Panama or Luxembourg and all the revenues go into that company even if they were earned in the country of origin, no tax is paid at home.

Of course, if you take the money out and put it in your home bank account, you are supposedly then liable to tax. But it can stay offshore until you retire abroad, or you can use it to buy property or diamonds abroad.

According to the Guardian, “More than £170 billion of UK property is now held overseas. Nearly one in 10 of the 31,000 tax haven companies that own British property are linked to Mossack Fonseca.” British property purchases worth more than £180 million were investigated in 2015 as the likely proceeds of corruption — almost all bought through offshore companies — according to Land Registry data obtained by Private Eye.

The British Overseas Territories, like the British Virgin Islands or Jersey, operate for these purposes and this is the main source of revenue for these islands. In the US, Americans can set up an “offshore company” in Delaware or other states like Nevada — they don’t even need to go to Panama.

Two-thirds of the purchases were made by companies registered in four British Overseas Territories and Crown dependencies which operate as tax havens: Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man, and the British Virgin Islands.

The British Overseas Territories play an important part in the role that British imperialism has developed as the global financial center and conduit for international capital flows. These old colonies in the Caribbean were encouraged to develop financial services industries, by allowing the former colonies to benefit from tax treaties with the UK (and thereby access to the global financial system), while making their own arrangements regarding the local taxation of offshore shell companies.

As I have pointed out before, large global corporations with many operations can switch their tax liability around the world to find the lowest tax burden through special companies set up in these tax havens. Barclays has thirty-plus of such shell companies to avoid tax.

In his devastating book, Treasure Islands, Tax Havens, and the Men who Stole the World, Nicholas Shaxson exposes the workings of all these global tax avoidance schemes for the big corporations and how governments connive in it or allow it.

There are three ways that somebody (a person or corporation) can get their tax down or pay none at all. They can lie about their earnings (tax evasion); they can employ batteries of accountants to come up with schemes that are designed for no other purpose but to avoid paying tax (tax avoidance); or they can simply refuse to pay (tax compliance).

One of the most notorious cases of refusing to pay tax that is due under the law has been that of the global mobile telephone corporation, Vodafone. It owed the UK government £6 billion in taxes because it had salted away profits in a tax haven subsidiary (registered in Luxembourg) purely to avoid paying UK taxes.

The law was clear. The UK government pursued the company for the money but at the last minute, the leading UK tax official at the time did a secret deal with Vodafone for the company to pay just £1.2 billion over five years.

The reason given for the deal when it was exposed was that it was a “good cash settlement.” But that’s only because Vodafone was fighting every inch of the way through the courts to avoid a settlement (although it was about to lose).

How many of us would get such a deal if we refused to pay tax due? Yet there are 190 similar disputes going on with UK companies who have put profits in tax havens to avoid paying. And these companies are now using the Vodafone precedent as a reason for refusing full payment.

According to the Tax Justice Network, around £25 billion is lost through tax avoidance schemes in the UK, while up to another £70 billion is lost through tax evasion by large companies and rich individuals.

Also, because of the lack of tax staff, another £26 billion goes uncollected. This £120 billion would be more than enough to avoid the huge cuts in government spending and extra taxes on average households implemented by the UK government with which it claims that we are “all in it together.”

The rotten irony is that the very people in accounting firms organizing these tax avoidance scams get jobs in the government tax collection departments to chase tax avoiders! Edward Troup, the boss of the UK’s Revenue & Customs, the government department overseeing a £10 million inquiry into the Panama Papers, was a partner at a top London law firm, Simmons & Simmons, which acted for Blairmore Holdings and other offshore companies named in the leak, when the firm had contacts with Mossack Fonseca.

Troup, who described taxation as “legalized extortion” in a 1999 newspaper article, built a career advising corporations on how to reduce their tax bills before leaving Simmons & Simmons to join the civil service in 2004.

While working in London, Troup led the opposition to reforms put forward by the then–prime minister Gordon Brown to curb corporate tax avoidance in 1999, putting out a press release headed: “City lawyers call on government to withdraw proposals to tackle tax avoidance.” He criticized the proposed laws for giving “wide-reaching” powers to the Inland Revenue.

Of course, tax breaks for corporations and the rich along with tax increases for the average household and the poor are not confined to the UK. International Monetary Fund researchers estimated in July 2015 that profit shifting by multinational companies costs developing countries around $213 billion a year, almost 2 percent of their national income. The Tax Justice Network estimates the global elite are sitting on $21–32 trillion of untaxed assets.

Thomas Piketty has pointed out that, in 2014, the LuxLeaks investigation revealed that multinationals paid almost no tax in Europe, thanks to their subsidiaries in Luxembourg. Piketty pointed out that, in many areas of the world, the biggest fortunes have continued to grow since 2008 much more quickly than the size of the economy, partly because they pay less tax than the others.

In France in 2013, a junior minister for the budget calmly explained that he did not have an account in Switzerland, with no fear that his ministry might find out about it. It took journalists to reveal the truth.

Piketty’s economic colleague, Gabriel Zucman, recently published a book showing that $7.6 trillion in assets were being held in offshore tax havens, equivalent to 8 percent of all financial assets in the world. In the past five years, the amount of wealth in tax havens has increased over 25 percent. There has never been as much money held offshore as there is today.

In the US, few big companies actually pay the official 35 percent corporate tax rate. Profits are up 21 percent since 2007, while corporate America’s total tax bill has dropped 5 percent.

The best-known trick is so-called tax inversions: US companies can move their headquarters abroad, avoiding the taxman while keeping executives stateside, scoring government contracts, and taking full advantage of public benefits for employees. Walgreens, which makes a quarter of its money from Medicaid and Medicare, proposed moving to Switzerland last year, only to change plans following a public outcry.

And guess where inversions were first started? Panama! Tax inversion was pioneered in 1983, when the construction company McDermott International changed its address to Panama to avoid paying more than $200 million in taxes.

The tax lawyer who masterminded the “Panama Scoot” was later immortalized in an operetta performed for his colleagues. The thirteen-minute operetta, Charlie’s Lament, told how the party’s host, John Carroll Jr, invented a whole category of corporate tax avoidance and successfully defended it in a fight with the Internal Revenue Service. The lawyers sang:

The Feds may be screaming,

But we all are beaming

’Cause we’ll never pay taxes,

We’ll never pay taxes,

Never pay taxes again!

Inversions aren’t the only way to dodge the taxman. Foreign profits of US corporations aren’t taxed until they are “repatriated,” so companies can hoard earnings in subsidiaries or divisions abroad. (Ireland just shut down the “Double Irish” offshoring trick used by Apple, Google, Twitter, and Facebook.) Between 2008 and 2013, American firms held more than $2.1 trillion in profits overseas — that’s as much as $500 billion in unpaid taxes.

American corporations are making billions in record profits, but sixty of the nation’s largest companies are parking 40 percent of their profits offshore in an effort to escape US taxes, a survey by the Wall Street Journal reveals. In President Obama’s last budget for 2016, he proposes to stick a one-time “transition toll charge” of 14 percent on the more than $2 trillion in corporate earnings parked overseas, regardless of whether they’re brought back stateside.

The estimated $280 billion in tax revenue would be earmarked for upgrading highways and infrastructure. The proposed one-time tax is aimed at just one of the various loopholes and maneuvers that domestic businesses use to offshore their profits, beyond the reach of Internal Revenue Service. Congress may block this.

Apart from greed, there is a very good economic reason for a tax system that benefits corporations and the rich and hits the average family and the poor. Lowering the corporate tax burden has been a big part of counteracting falling profitability of capital in the major economies.

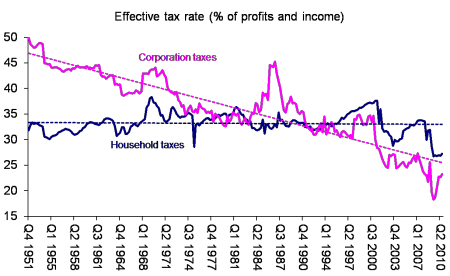

Look at the trend in the effective tax rate on US corporations compared to the effective tax rate on their employees. The effective tax rate is a measure of what is actually paid compared to income rather than the headline tax rate. Whereas in the 1950s, US corporations paid an effective tax rate of around 40–45 percent of profits, by the 1990s, that rate had fallen to 30–35 percent.

In the last decade, it dropped further to under 25 percent and reached an all-time low in 2009 at the depth of the Great Recession. In his latest budget, the UK Chancellor George Osborne announced a further cut in corporation tax to a record low for G7 countries of 17 percent by the end of this current parliament.

The trend is clear: corporations are being taxed less and less to preserve their profitability. In contrast, the effective personal income tax on employees has remained pretty steady at about 35 percent. Less tax for capitalists and more tax for workers.

While corporations and wealthy individuals pay less tax at home and salt much of their gains in tax havens abroad, the rest of us have had to pay for the loss of these tax revenues. As the effective rate of US corporation tax plunged, income taxes on households were static until the Great Recession led to unemployment and falling incomes. Median income in the United States is down 8.5 percent since 2000.

And the wealth of US families has fallen sharply since 2007 and is roughly back to where it was twenty-four years ago.

The bottom 90 percent of Americans have seen their overall income drop, while low interest rates and quantitative easing have dramatically helped the top 10 percent. If the super-rich actually paid what they owe in taxes, the US would have loads more money available for public services.

What needs to be done? In the UK, the government should end the tax-haven statuses of the overseas territories. Companies there must pay the same taxes as in the UK. If the poorest in these tiny enclaves suffer loss of income, then the UK government can compensate them. Governments should agree to an international agreement to end tax havens like Panama and impose economic sanctions against them if they won’t.

Above all, the tax avoidance operators must be taken over. We need to take into public ownership and control the major banks and financial institutions that dominate the globe and encourage and provide services for the rich and corrupt elite (as revealed in scandal after scandal).

This would provide not only extra tax revenue to meet the real needs of people in public services and investment, it would also enable banking and finance to be put to use as a public service in providing credit for investment.

Of course, such measures will be vigorously opposed by most current governments and their rich backers and ignored by most left opposition movements. But without such measures, the Panama story will continue.