Beyond the Model Minority Myth

Asian Americans' long history of challenging stereotypes has often overlooked the ways in which capitalism forges racial identity.

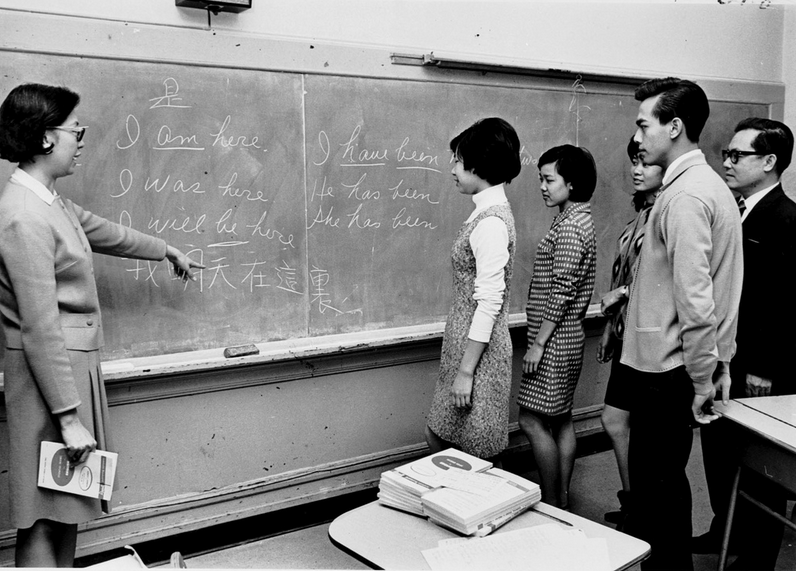

An English class for Asian-American ILGWU members of Local 23-25 in December 1968. Kheel Center / Flickr

In his May 2014 commencement speech to Yale’s Asian-American alumni, jazz musician and Harvard professor Vijay Iyer said, “To succeed in America is, somehow, to be complicit with the idea of America — which means that at some level you’ve made peace with its rather ugly past.”

He was referring to the upward mobility of large numbers of Asian Americans, which, he argued, came at the expense of other people of color.

A few months later, this sentiment was echoed by the online forum ChangeLab, which announced a new social media campaign, #ModelMinorityMutiny, designed to identify and reject the insidious construction of Asian Americans as a “good” minority, a designation that has been used as a means to justify and perpetuate racism against blacks in particular.

These statements have been part a growing push among younger Asian Americans to name and decry the participation of Asians as a racial group in white supremacy. This line of inquiry, which has sharpened in the wake of the high-profile, black-led protests against police violence, has so far resulted in several ongoing discussions and at least a few powerful shows of on-the-ground solidarity in the aftermath of Ferguson under the banner #Asians4BlackLives.

New York-based organizations like CAAAV: Organizing Asian Communities and DRUM – South Asian Organizing Center have mobilized small demonstrations explicitly in support of black families affected by police brutality in Queens and Manhattan. On the opposite coast, the Oakland-based group Seeding Change launched an online “Selfie Action” in April to collect photos of Asian Americans holding signs declaring their support for the indictment of Chinese-American NYPD officer Peter Liang, who had shot and killed 25-year-old Akai Gurley during an unauthorized vertical patrol in East New York.

The criticism of Asian Americans’ complicity in a power structure that disregards black life has emerged as a significant theme among young activists eager to ally with the Black Lives Matter movement. Underlying this turn seems to be the desire to expose the shortcomings of what scholar Jared Sexton has called “people of color blindness,” or the tendency among progressives to flatten or elide the experiences of all non-white people under one umbrella.

As Sexton notes, this move may obscure or appropriate the specificities of black suffering. Claiming that police violence and mass incarceration affect “people of color,” for example, diminishes the fact that blacks remain the primary and most disadvantaged targets of both — Latinos on average receive shorter sentences than blacks, even as their rates of imprisonment steadily climb, and Asians have the lowest incarceration rates of any group, whites included.

In other words, declaring “my experience is not like yours” may occasionally serve as a necessary intervention into too-simplistic readings of racism in the US that collapse the experiences of different racial groups. In the words of Rinku Sen, “As people of color, we are not all in the same boat.”

But if the recent calls to question complicity have been useful in highlighting the disparities in power and access to resources that exist between different subordinated groups in the US, they have also tended to function as inward-looking moral strictures, rather than explanations for how such disparities came into being.

For example, following the death of twenty-five-year-old Freddie Gray at the hands of Baltimore police, Asian-American rapper Jason Chu released a short spoken-word video titled “They Won’t Shoot Me.” In the video, Chu, clad in a military-style tee proclaiming “ASIAN,” rapped a list of his economic and social comforts, concluding with the line “that’s privilege” as “I am not Freddie Gray” flashed across the screen.

Like 2014’s much-shared We Are NOT Trayvon Martin, a Tumblr of mostly white people cataloguing the injustices that white privilege had allowed them to avoid, Chu’s public display of privilege-checking was well-intentioned, but at times blurred into a kind of solipsism — was he speaking out against police repression or simply talking about his own life?

Similarly, at the end of 2014, Hyphen magazine published “An Apology to Black Folks,” in which Taiwanese-American author Kai-Ming Ko excoriated both himself and his fellow Asian Americans for acts of state violence against black communities, including the failures to indict the policemen who had murdered Eric Garner and Michael Brown. Lamented Ko, “We messed up.”

He went on to cite the ways in which he believed Asian Americans had bolstered a system of white supremacy, including “pay[ing] taxes which support mass incarceration” and making the choice to “eat, shop, work, own businesses, study, and live in communities where white supremacy is the dominant operating racial framework.”

Indeed, global capitalism induces Americans to participate in one unjust system or another — buying sweatshop-manufactured clothes or eating produce harvested by poorly paid migrants comes to mind — which largely rely on the exploitation of non-white workers. However, like appeals to ethical consumerism, Ko’s condemnation of “complicit” everyday actions such as eating and shopping places its emphasis on individual behaviors, offering little in the way of suggesting how Asian Americans might collectively mobilize to confront and attack racism and inequality.

Historically, the term “Asian American” didn’t emerge until the 1960s, and since then, has been an extremely fluid category — shifting from narrow to capacious in line with political and economic trends. As a Census designation, “Asian” accounts for less than 5 percent of the US population, but currently encompasses individuals from over forty-five national origins, speaking over a hundred languages and dialects.

According to a recent report from Third Way, the rate of Asian political participation in the US remains relatively low, though the fever pitch of Republicans’ xenophobic rhetoric around immigration over the last few decades has swayed them somewhat toward the Democrats. While Asians tend to support a range of progressive causes like health care and (contrary to popular perception) affirmative action, they currently hold limited political power and are the targets of little campaigning outreach.

What, then, has given rise among progressives to the idea of Asians as unique collaborators in the state oppression of the black population? One potent source is the model minority narrative, which is precisely what groups like ChangeLab are criticizing and hoping to overturn. Founder Scot Nakagawa, who calls the model minority myth one of the many “levers” of white supremacy, notes that a number of Asians “have internalized the myth, and along with it, negative stereotypes about Black people, making the case through their experiences that the model-minority myth is the flip side of anti-blackness.”

Inflamed in the twenty-first century by cultural commentators like Amy Chua (of Tiger Mom and Triple Package fame), the idea that Asians’ rigid cultural values have enabled them to bootstrap their way out of hardship has been in circulation at least since the end of World War II. The Color of Success, a recent book by historian Ellen D. Wu, locates the roots of this insidious mythology in the postwar rise of racial liberalism as the dominant framework for addressing matters of race in the United States.

The United States’s struggle for global ascendency after World War II and through the Cold War prompted liberals to argue for the loosening of racial restrictions on Asian Americans in order to better forge ties with Asian nations and model the kind of egalitarian democracy they claimed to promote overseas.

Following the internment of Japanese citizens during the war and the Red Scare of the 1950s that cast Chinese immigrants as potential communists, liberal Chinese- and Japanese-American groups fought hard to combat the “yellow peril” stereotype that branded Asians as perpetual foreigners and subjected them to violence and exclusion from jobs and neighborhoods.

Groups like the Japanese American Citizens League encouraged their constituents to participate in actions that would reinforce the idea of Asians as assimilable model citizens, including enlisting in the military and suppressing youth delinquency. Such groups pressed for positive representations of Asians by releasing texts that extolled the virtues of Asian culture and trotting out respectable spokespeople to serve as ambassadors of the race.

By the 1960s, the state was eager to contain the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement and, among other tactics, found a racial foil in the “successful” Asian immigrant, a trope that could be brandished to discredit the movement and attribute blacks’ disenfranchisement to a “culture of poverty.” The infamous Moynihan Report, for instance, credited the “close-knit family structure” of the Japanese and Chinese with their uplift in society, and juxtaposed this with “black matriarchy,” arguing that the latter had been responsible for the entrenchment of blacks in poverty.

In addition to providing crude justification for anti-black racism, such narratives also made it possible for liberals to conveniently dismiss the horrors of internment and Chinese Exclusion. As Wu notes, “Japanese American ‘success stories’ of the mid- to late 1950s redeemed the nation’s missteps and reinforced liberalism’s tenets, especially state management of the racial order.”

Thus, the overlapping desires of both the government and liberal Asian-American advocacy groups to incorporate Asians (albeit in a regulated way) into the body politic produced the narrative of immigrant success that became the model minority myth.

Wu’s book is notable in that it foregrounds the specific ways in which Asian groups actively participated in the construction of the fateful mythology, a piece of history heretofore largely ignored. However, Wu is also careful to note that “model minority status was, for the most part an unintended consequence that sprung from many concurrent imperatives in American life.”

In other words, discussing certain Asian groups’ material advantages today as a type of transhistorical “privilege” or “complicity” with power — rather than the result of a specific set of immigration and domestic policies that have aligned with shifting national attitudes — mystifies the mechanisms of capitalism rather than elucidating them.

To better explain the position occupied by Asians in the current hierarchy of power, more useful questions to ask might include: Which political structures have enabled certain Asian-American communities to flourish economically, and in which instances has this occurred at the expense of other ethnic and racial groups? How does the “model minority” narrative operate as part of the legacies of colonization, slavery, and immigration that have shaped the racial hierarchy in the US? And how are race and class boundaries in the US currently enforced and upheld?

The contemporary iteration of the model-minority stereotype was sealed into place following the 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act, which abolished strict national-origin quotas and instead prioritized family unification, education, and professional skills. Sociologist Jennifer Lee — whose new book The Asian American Achievement Paradox examines this phenomenon in detail — argued recently in Contexts that the Asian immigrants who enter the US are “highly selected, meaning that they are more highly educated than their ethnic counterparts who did not immigrate.”

According to Lee, this hyperselectivity also means that those who are admitted to the US have the capital to create “ethnic institutions such as after-school academies and SAT prep courses” that then become available to working-class co-ethnics, boosting rates of education for the entire group.

Other scholars, such as Tamara Nopper, have focused their attention on how domestic policies, rather than immigration provisions, have aided Asian-origin groups. In an article for Everyday Sociology, Nopper argues that numerous domestic initiatives, such as the White House Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, have provided financial support to Asian immigrant communities that have not been as readily available to other communities of color.

As a result of both the immigrant selection process and domestic policies, Asian Americans currently hold the highest median income and education levels of any race today, with climbing wealth levels projected by the Federal Reserve of St. Louis to overtake those of whites within two decades.

However, to interpret this data as evidence that “race” has caused Asian success, or that Asians have somehow accessed the spoils of white supremacy, is to elide racism and class in a way that misunderstands how the particular racialization of Asians in America augments capitalist restructuring that demands increasing numbers of both knowledge workers and service workers while simultaneously attempting to press the wage floor lower for all.

Terms like “model minority” and even the awkward “honorary whites” by definition construct Asian Americans as “not (quite) white” even as they position the group on the advantaged end of people of color. Therefore, it is not that Asians are being assimilated into whiteness — as various commentators have argued for years — but rather, that they are being assimilated into an evolving formulation of “not black”-ness.

As Nopper has provocatively put it, “Asian Americans and Latinos don’t need to be assimilated (according to most traditional measures), be phenotypically white, be accepted by white people, like white people, or be free from white violence and racism, to have structural power in comparison to, and over African Americans.”

We might further investigate how the racialization of Asians between two color lines — white/non-white and black/non-black — reproduces discrete labor forces in the US today. On one hand, middle- to upper-class Asian Americans have largely escaped being marked as part of what Salar Mohandesi has described as a disenfranchised “surplus” population vulnerable to police violence and incarceration. The entry of these Asians into elite universities and high-paying industries such as tech is often used to prove that capitalism functions as a meritocracy.

Yet even in tech and other fields in which they are purported to “dominate,” Asians consistently make less than their white counterparts. A 2012 report from the Economic Policy Institute found that they were also more likely to be laid off during the recession and slower to find jobs than whites in comparable positions. In other words, being racialized as non-black allows Asian Americans to access certain top-tier positions, while being non-white consolidates them as discounted, expendable labor within a number of rapidly growing industries.

At the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum, low-income Asian groups (Hmong, Cambodian, Bangladeshi, Laotian, and Fujian Chinese, among others) populate the service sector and the informal economy, where, like other groups that struggle to get by on low-wage work, they suffer from high rates of poverty, job precarity and may be subject to state surveillance (such as police raids on massage parlors in Queens.)

A 2014 report by Asian Americans Advancing Justice LA found that Asians were overrepresented not just in STEM fields, but also in “personal care and service occupations,” including nail salons, garment production, and taxi and livery drivers. That these roles sound like stereotypes indicates how business continues to use powerful racist stereotypes to segment and exploit workers and how sweeping categories like “Asian” hide deep class divisions.

As the evolution of capitalism continues to reset color lines in the US, fighting inequality will entail not simply challenging stereotypes and unlearning racism at the individual and community level, but attacking the economic system that requires racist civic hierarchies to construct and maintain divisions of labor.

Asian American support for broad programs of economic redistribution will go much further than consciousness-raising to overturn the “model minority” myth. Such redistributive initiatives would not only benefit the Asian groups that currently experience high poverty rates and diminished life chances, but would also dramatically lessen the longstanding material inequalities between blacks and non-blacks more broadly.

While campaigns like #Asians4BlackLives and #ModelMinorityMutiny ostensibly extend a hand of solidarity to other racial groups, they also run the risk of falling into a certain kind of “good ally” model whereby they divert focus from the cause they support (“black lives”) back onto themselves (“Asians”). Such campaigns may also implicitly suggest that those not organizing under their specific banners are necessarily opposed to struggle for racial justice, when in reality, many could simply lack adequate information on the issue.

Recent media coverage of the Peter Liang indictment, for example, has suggested that Chinese Americans in New York have been sharply divided over the case, with conservative elements demanding Liang’s acquittal and progressive groups rallying behind the Gurley family.

But perhaps an even greater number of working-class Chinese immigrants are disconnected from politics altogether. Reporter Vivian Yee, who covered the Chinese community’s rift over Liang, noted of her interview subjects, “As garment factory workers, appliance salesmen and waitresses [in Sunset Park] reached the end of the workday one evening last week, many said they had not followed the case. Most who were familiar with it declined to attach any political significance to the officer’s indictment, insisting it was not their place to do so.”

Furthermore, a report from the New York City Campaign Finance Board found that in the 2008 New York City election, “tracts with higher percentages of Asians had lower voter participation rates, even when all other factors (most notably language and naturalization status) were taken into account.” Though voting is not the sole metric by which one can gauge a group’s political participation, such a statistic nevertheless suggests that Asian Americans have yet to galvanize as a meaningful force in New York City politics, though the city is home to over a million Asians — more than any other US city.

As the number of Asian immigrants to the US continues to climb, Asian-American identity — as fraught as it has been historically — may serve as a necessary strategic essentialism in the struggle for equality. But utilizing that identity to build much-needed political power among disparate communities will require the understanding that simply refashioning the public perception of Asian Americans will not be sufficient to challenge the existing social order.

Our decades-long struggle to control our image — including contemporary efforts to quash the model-minority stereotype — will be toothless without a politics of radical wealth redistribution to attack the economic system that exploits and oppresses all workers.