An ABC of Authoritarianism: Argentina, Brazil, and Chile

Aside from its authoritarian ambitions, the Trump administration shares few of the conditions of Latin America’s past military dictatorships. But its echoing of fearful rhetoric about an “enemy from within” remains just as dangerous today.

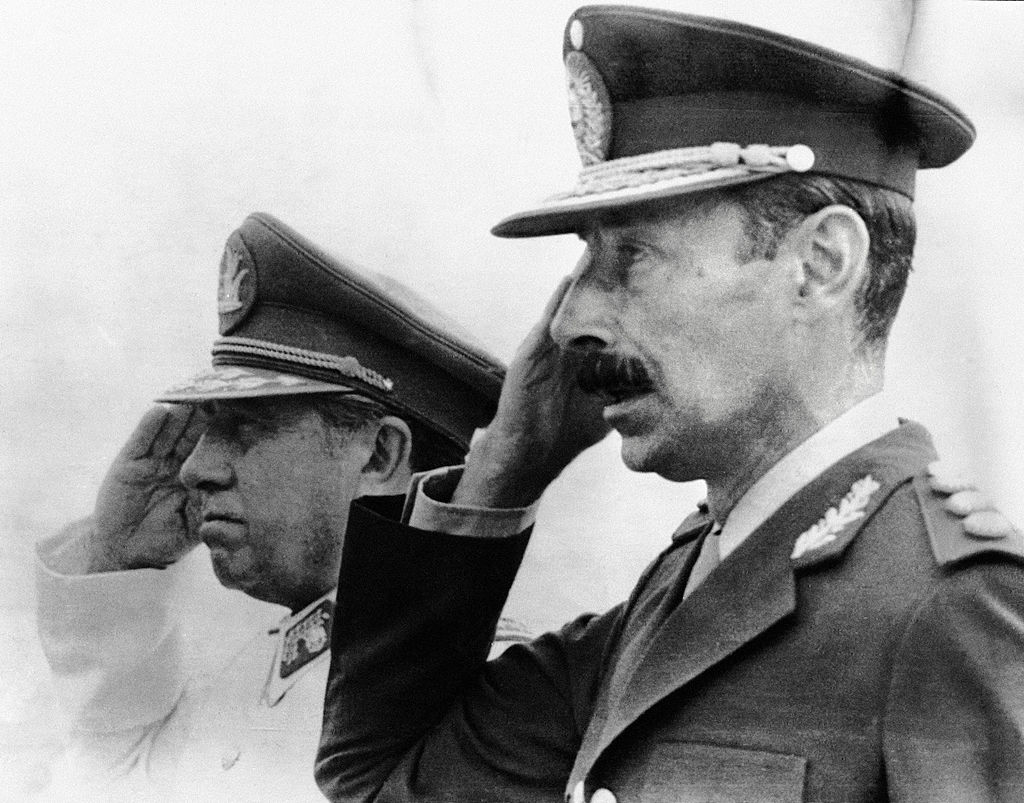

Photograph taken in Chile in 1978 of General Augusto Pinochet (L) and his Argentine counterpart General Jorge Videla. (STR / AFP via Getty Images)

Between the mid-1960s and the 1980s, military dictatorships dominated South America, epitomized by the ABC countries: Argentina from 1966 to 1971 and 1976 to 1983, Brazil from 1964 to 1985, and Chile from 1973 to 1990. Three historians of Latin America ask what, if anything, military rule in these three countries reveals about the current lurch toward authoritarianism in the United States.

These remarks, presented at the annual meeting of the American Historical Association, may be read as a primer on the different strains of authoritarianism then and now, there and here.

Across the comparisons, three aspects stand out. To start, the fearful rhetoric of combating internal enemies, common to South America’s military dictatorships, has been echoed by Trump administration officials at the highest levels. Contrasts, however, loom larger, in everything from the current administration’s source of legitimacy (elections, as opposed to military coups), to its personalistic style, to its relative ability to wield untrammeled power. Finally, the South American cases remind us that people resisted authoritarianism under far more perilous conditions than anything people in the United States have faced to this point. We are going to need more opposition to stem the rising authoritarian tide.

1

Argentina

There are four ways in which MAGA authoritarianism echoes the Argentine dictatorships of the Cold War era, and especially the horrific regime installed in 1976.

The first echo is the notion of internal enemies. Argentina’s Cold War regimes were buoyed by the National Security Doctrine, which justified repression against perceived domestic enemies. This justification was made most infamously by the military governor of Buenos Aires province in 1977, when he declared, “First we kill all the subversives; then, their collaborators; later, their sympathizers; afterward, those who remain indifferent; and finally, the undecided.” In Argentina, the dictatorship identified an ever wider array of subversives and internal enemies. Here in the United States, one sees parallels in the notion of an internal enemy that grows in concentric circles: immigrants, voices against the genocide in Gaza and in support of immigrants, civil servants fired by DOGE, educators, students, and poor people punished by the suspension of food benefits. And, of course, the Trump administration’s deployment of troops to blue cities exemplifies the construction and persecution of internal enemies.

The second echo is instances of visible and invisible state violence and terror. In Argentina, violence was often clandestine; people disappeared late at night. But not always. Violence and terror also occurred in broad daylight. The latter is plain to see in the United States today, in the arrests of students in broad daylight, workplace raids around the nation, and in the network of prisons holding immigrants for deportation. And there is Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and its masked agents of terror forming an extrajudicial paramilitary force akin to the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance.

A third echo is perhaps less dramatic. It lies in the dissonance of normal, daily life continuing apace during terror. In recent years, some of the best work about the Argentine regime has been related to daily life under authoritarianism. Works by historians like Sebastián Carrassai, Marina Franco, and David Sheinin have looked at the many ways ordinary individuals lived and often thrived under military rule — a type of social complicity. Many in the United States have probably felt that dissonance: at school bake sales in the shadow of ICE raids, in naturalization interviews in Lower Manhattan next door to ICE’s New York headquarters.

Yet we should be cautious about drawing too many equivalencies. South America certainly shows how countries can slip into authoritarianism, but Donald Trump was returned to office through the electoral process, not a military coup (though the attempted putsch of January 6, 2021, may be closer to the latter than the former). US institutions, though revealed as weak, have not been formally suspended as in Argentina.

A final, potentially more hopeful echo comes in thinking about resistance. Over the past year, there have been many think pieces about how Latin America provides examples of how to combat authoritarianism. In the Argentine case, it is important to note that resistance to the regime was not immediate, nor was it embraced by most ordinary Argentines. Many in this country know of the Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, the white-scarved marchers demanding to know of their loved ones’ whereabouts. But that movement, which was founded in 1977, spent years in relative isolation. It was only in 1981, five years after the military coup, when the regime’s crimes were known and condemned around the world, and with the economy in free fall, that Argentina’s human rights movement began to gain broader acceptance, and the process still remained slow.

To say as much is not to fall victim to the paralysis of pessimism, which is another tool of authoritarianism. We are seeing acts of resistance big and small: the everyday individuals stopping ICE and protecting their neighbors, the US council of Catholic Bishops’ special message condemning the persecution of immigrants, the massive marches and demonstrations across the United States, and even the American Historical Association business meeting in which members voted overwhelmingly to condemn attacks on core principles of education and to express solidarity with Gaza, despite the Executive Council’s veto of the resolutions and violation of the democratic expression of the membership.

It is not clear what successful resistance would look like or how it might play out in the United States, but the outrage and widespread mobilization sparked by the recent ICE murders in Minneapolis may provide a glimpse of the growing consensus that what is happening here cannot be permitted.

— Jennifer Adair

2

Brazil

More than anything else, comparing Trumpian authoritarianism with the Brazilian military regime yields contrasts.

The most basic contrast between Trumpian authoritarianism and military-government authoritarianism is how personalistic the administration is and how institutional Brazil’s military governments were. Trumpism is, as the term suggests, a one-man show, dependent upon Trump’s personal appeal, whims, obsessions, and vanity, while the Brazilian generals were anti-personalist as a matter of policy.

And yet there’s a funny thing about Trumpian personalism. Personalism, as a political attribute, tends to be identified with popularity, but Trump has some of the lowest approval ratings in history. On that basis, one could say that he is probably less popular than any of Brazil’s general-presidents, save perhaps for the last one, an equestrian who famously remarked that he preferred the smell of horses to that of the people.

But while Trumpian authoritarianism is deeply unpopular, it is mobilizing for a minority of hardcore supporters, whereas the Brazilian military dictatorship was demobilizing. Even at its peak, pro-regime propaganda in Brazil aimed at fostering quiescence, passivity, acceptance, and, at its most ambitious, enthusiasm, but nothing in the way of active, participatory support by anyone outside of the security services. Trump, by contrast, has mobilized his hardcore supporters against institutions and individuals identified as his enemies, most famously on January 6, 2021, but in his second term as well. It is well known, for example, that some GOP legislators have been reluctant to put any daylight between themselves and the administration, not only because they are afraid of being primaried but because they fear for their own and their family’s physical safety. Here we’re much closer to Italy in the 1920s than Brazil under the generals.

Back to Brazil: in the early 1970s, at the height of military rule, there was much that was buoying the regime’s position. This was the period of the so-called economic miracle, during which GDP growth topped 10 percent per year and industrial growth soared to twice that. Yes, we know that the spoils of that economic growth went overwhelmingly to the top 10 percent of households, but to residents of and visitors to the cities of the country’s southeastern core, progress was evident. The interior was another story — but that was the point, the national project of the Brazilian generals sharing a decades-old policy predilection of favoring the urban southeast.

The words “national project” present another contrast between military-government authoritarianism and Trumpism. Put briefly, the Brazilian generals had a national project; the Trump administration does not. The Brazilian national project centered on industrialization, but it embraced modernization more broadly, including developing transportation and communication infrastructures of national scope, educational expansion, and some social welfare measures; after 1973, it included diversifying the country’s sources of energy. After 1974, it also featured a ramping up of the public sector. The latter was fed to the wolves in the neoliberal 1990s, but elements of the national project remain in transportation infrastructure, flex-fuel cars, and the Itaipu dam. The generals did not bring Brazil into the First World, as some dreamt, but they had a future-looking project that produced things that are still of use.

Trumpian authoritarianism, by contrast, has no national project. Yes, everyone has seen the red hats, but almost ten years on we have yet to learn when America was great, never mind be presented with a policy map of how to get there (again). And even if we did, the backward-looking nature of the slogan contrasts with the sense of futurity presented by and for the Brazilian military regime. Rather than a national project, Trumpian authoritarianism seems to have as its only aims economic and psychological self-dealing.

Looking at the two regimes from a different angle, one must say that Trumpian authoritarianism is much less complete. Brazil and the United States are both federal republics, but Brazilian federalism was much more constricted under military rule than US federalism has been. The power of the states, and of smaller jurisdictions within the states, still stand in the United States to a degree unseen in Brazil under the generals. To take only the most dramatic example, in November, a democratic socialist was elected mayor of this country’s most populous city; just weeks ago, he was sworn in and took office without incident. Can one imagine a similar scenario occurring in military-ruled Brazil? As it turns out, we don’t have to. In November 1968, a democratic socialist was elected mayor of Brazil’s key port city of Santos. Before he could take office, however, Esmeraldo Tarquínio fell victim to cassação — that is, the military government suspended his political rights to prevent him from taking office.

From contrasts to quotation:

He is behaving like an emperor since the inauguration. . . . He is firing the best people from high positions and replacing them with those who contributed significantly to his campaign fund, some of whom have vested interests in the matters they are supposed to regulate. Congress, which should be doing something to counteract efforts to concentrate all power in the presidency, talks a lot, but does nothing. . . . It is disgraceful, and we wonder what kind of country this will be after the end of this term. All the social welfare measures are being cancelled, and added support is being given to business and the wealthy classes. . . . One of the worst actions is the increased effort to silence opposition by the newspapers, TV, radio, etc.

That is from a letter by the anthropologist Betty Meggers. It is not from 2025 or 2026 but 1974, referring to Richard Nixon, a reminder that we need not go as far as South America to find precedents for Trumpian authoritarianism. But Meggers — who worked in Brazil from the 1950s through the period of military rule and beyond — went on to license exactly that comparison, adding, “We are resembling Brazil more every day!” Contrasts aside, perhaps we are.

— James Woodard

3

Chile

The military dictatorship that had overthrown the Popular Unity government on September 11, 1973, was at the height of its power when I arrived in Chile in November 1976. The commanders had abolished parliament, political parties, the rule of law, and human and civil rights. Chile was under curfew, so as night approached, the streets emptied and businesses closed.

The people I met felt fear, sadness, and confusion, but also anger, courage, and determination, emotions felt by those who oppose the Trump administration in the United States today.

Street protests were prohibited, so for May 1 the opposition held a special mass for St Joseph the worker in the downtown cathedral, one of the few safe spaces in Santiago. The homilies and sermons were given by a boy whose father was disappeared, a mother whose daughter was disappeared, a teenager who worked in a food kitchen, a man who had pooled his funds with other workers who had lost their jobs so they could produce something to sell to have minimal income to support themselves and their families. Following the service some people shouted, “Abajo con la Junta, Libertad a los presos politicos!” while others yelled, be quiet, the DINA (Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional, the secret police) are here. Police surrounded the area outside the cathedral with German Shepherds who looked ready to pounce. The crowd dispersed rapidly. The police arrested a few people but most made it home.

Despite the terror and brutal repression, the Chilean left continued to organize, hope, and fight. Members of the opposition understood they were risking their lives, but they continued because they believed they could end the dictatorship and build a socialist Chile.

Obviously, the differences with the United States are huge. The American Historical Association Conference would not be taking place and we would not be presenting these remarks if this were a military dictatorship. Public expressions of resistance, such as street protests and indoor rallies, would experience massive repression. Although the level of repression has increased in this country, most of us don’t go to demonstrations thinking we may not return. Although, after the recent ICE murders in Minneapolis, this is less and less true.

Differences between the Chilean and US left abound. Few US organizations or parties have the level of organization, historical memory, experience of repression, and the political and moral commitment to resist that the Chilean left did. (This does not mean the entire Chilean left behaved heroically.) At the same time, the response of the tens of thousands of people in the United States who have come out to support the Palestinian people as well as immigrants, to defy ICE, and been arrested and brutalized is impressive and inspirational. We need to sustain and deepen our commitment to justice.

One other major difference, of course, is that the Chilean military overthrew the Popular Unity government of Salvador Allende. To date, key sectors of the US military have not fallen in line behind Trump’s attempts to violate the Constitution. That is why Trump has turned ICE into his own private militia and removed top military officers who disagree with him.

One parallel between the Chilean armed forces in the 1970s and ’80s and ICE in the United States today is that both consider and treat people in their respective countries as the enemy other. In 1964, the US Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, instructed Latin American militaries that they needed to defeat the “internal enemy,” those General Augusto Pinochet referred to as “intrínsicamente perversa” (inherently perverse), since they were the ones that posed the greatest threat to the nation. This policy reversed the precept that the role of the armed forces was to protect the nation from the external enemy, and instead had them target so-called subversives. Members of ICE did not receive this same indoctrination, but it is clear they consider anyone who opposes them a justifiable target. ICE agents, like the Chilean military and the DINA, have operated with impunity, believing that they will never face justice, let alone punishment, for their horrific acts of brutality. That belief proved wrong in Chile, and we need to make sure it is equally false in the United States.

In 2026 and the years that follow, we need to intensify our resistance, build community-based and nationally linked networks of opposition, provide support and solidarity to those under attack, and believe that, just as Chileans rid themselves of the Pinochet dictatorship, we will defeat the MAGA movement.

— Margaret Power