The Power of Power Structure Research

Emerging in the 1960s, power structure research — mapping who holds power in society, how those entities are connected, and how they use their resources to shape major decisions — has been an important weapon in civil rights, antiwar, and labor struggles.

(Leif Skoogfors / Corbis via Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Derek Seidman

Today it’s almost taken for granted that activist campaigns and organizing drives, including within the labor movement, have some form of a power research component to help shape strategy and tactics. But this wasn’t always the case.

In the 1960s, power structure research — which maps who holds power in society, how those entities are connected, and how they use their positions and resources to shape major decisions and policies — was fairly new. Inspired by academics like C. Wright Mills and G. William Domhoff and early movement practitioners like Jack Minnis, movement power research gained traction through groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee — or SNCC, the grassroots civil rights group that had a vibrant research department led by Minnis; National Action/Research on the Military Industrial Complex — or NARMIC, which functioned as a research wing of the Vietnam antiwar movement; and the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA), which became a major early proponent of power research.

Since then, power research has gradually taken off, becoming a critical arm of a range of movements, campaigns, and union drives.

Over the past sixty years, Michael Locker has been at the center of the rise of movement power research. He was first introduced to power research in the mid-1960s by the late Tom Hayden, an early leader of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Locker went on to cofound NACLA, and in 1968, he coauthored the famous “Who Rules Columbia?” pamphlet, which remains a cornerstone example of how to map out the power structure of universities.

Into the 1970s and ’80s, Locker deepened his commitment to power research, contributing to studies of the US banks behind South African apartheid and developing comprehensive surveys on the landscape of US corporate power. In the late 1970s, he cofounded the research firm that is today known as Locker Associates. According to one book-length study, Locker was a key pioneer of the corporate campaign strategy that is currently used by labor and other campaigns. Today, in addition to continuing to oversee Locker Associates, Locker lends his power research skills to Palestine solidarity campaigns and university organizing efforts.

Here Locker speaks to Derek Seidman at length about his long movement career, reflecting on the lessons and legacies of power research since the 1960s. The two discussed Locker’s personal journey, the origins of movement power research in the 1960s in civil rights, antiwar, anti-imperialist, and student organizing campaigns, and its wider popularization today, especially with the labor movement and through corporate campaigns.

Discovering Power Research in the 1960s

What’s the origin story behind your discovery of power research? And who and what were your early influences?

I had an academic background and a natural inclination toward research. I gravitated toward research as a tool for supporting action for achieving real change. That’s always been the underlying theme of my work.

The opportunity to really pursue this path came when I met Tom Hayden. He was a major inspiration for much of what has happened in my life. I first met Tom around 1962 or 1963, during the early years of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Tom and I talked about a lot of things, and he made a deep impression on me.

At the time, I was planning to go to the University of California, Berkeley, to study political sociology with Seymour Martin Lipset. He wrote the well-known book Political Man, which focused on voting and how to analyze it. I was interested in voting as a form of action and a way to create change. But even then, I had a sense that voting alone wasn’t enough to accomplish the change I wanted to see.

That’s when Tom suggested to me that I try to do some research on things that really affect the world. He said we could work together in Michigan, and he encouraged me to come to Ann Arbor. So I switched to graduate school at the University of Michigan and ended up working with him for about two years.

Tom was quite a mentor. He was a student of C. Wright Mills and had closely studied Mills’s work on the power elite. He introduced me to that world. He gave me six books when I first arrived in Ann Arbor and told me to read them before we talked. I read the books, and my understanding of power relations developed from there, all while working with him.

Do you remember what the six books were?

One was The Empire of High Finance, by Victor Perlo, a classic. Another was Anna Rochester’s Rulers of America. These were written in the 1930s and 1950s. Of course, there was The Power Elite, by Mills. The other three, I don’t remember.

Those books really instilled in me that you could understand the power structure and that this understanding could help formulate strategies and tactics to help create change. That thrilled me.

And again, this was going beyond voting. Voting is, of course, one way to achieve political objectives. But social movements are another way to achieve those objectives. And how do you give social movements the tools to create a strategy and tactics that are effective for creating change? That’s the overarching theme of how I was beginning to approach power research.

That’s also what Mills was talking about. He wanted to understand what was controlling US politics and economics that the American people were not aware of. And he thought that more awareness and consciousness of this would allow people to help develop a strategy and tactics to challenge that power.

It sounds like Mills was a key influence in shaping your discovery and embrace of power research. Were there others who influenced you?

G. William Domhoff comes to mind right away, though a little bit later. He wrote Who Rules America? in 1967, a very important book. Domhoff is more empirical and more academic than Mills and has less of an overt political agenda, but it was very informative on how to understand the power structure.

There was also a very important Soviet economist named S. Menshikov who wrote an important book called Millionaires and Managers. He was the son of the ambassador to the United States and lived in the US in the 1950s and 1960s. He studied the powerful financial institutions. That was a very important book for understanding where to look when doing power research.

You also discovered how power research could be applied to US foreign policy. Can you talk about that?

Foreign policy was a major inspiration in my embrace of power research. When the US invaded the Dominican Republic in April 1965, I immediately took the tools I was learning from Hayden and from the books I was reading, and I asked myself, “How can this intervention be understood in terms of power relations and the power structure of the United States?”

I uncovered the importance of the sugar industry, which was a mainstay of the Dominican economy. Several officials in the Lyndon Johnson administration who were running US policy toward the Dominican Republic were from the sugar industry, especially the US special envoy and mediator Ellsworth Bunker.

Bunker was the head of the second-largest sugar company in the United States, the National Sugar Refining Company, which had enormous interests in the Dominican Republic’s sugar industry. He was actually a very famous ambassador who later went on to play a leading role in the Vietnam War as well. I also uncovered several other key policy players with direct ties to the US sugar industry that shaped and implemented the US military occupation of the Dominican Republic. In my opinion, this played a major role in their actions.

You said that it really excited you when you discovered power research in the mid-1960s. Can you say a little bit more about what was so exciting for you about this?

I was a sociologist, and I also studied history. I had some engineering training, too, at Brooklyn Technical High School. My interest in power research was really about trying to figure out how to use my skills in those areas to develop ideas and methods to help the movement build strategy and tactics.

I think the overarching theme for me has always been trying to find a way to create meaningful social change that leads to better living conditions and a better world. And I’ve always wanted to know what makes things tick. How do they run? Why? I’ve always had a strong inclination to really understand how things work — not just describing them, but analyzing them, taking them apart, and understanding the various dynamics.

NACLA and Power Research

Let’s move on to NACLA. How did that get started?

Foreign policy was such an important component of the 1960s. What the US was doing overseas — and this is still true today — really mattered. The Vietnam War and, to some extent, the invasion of the Dominican Republic, sparked a lot of outrage. There were many campus protests and teach-ins.

The civil rights movement also played a huge role. The thing that actually got me excited to look at the Dominican Republic was from a SNCC newsletter. Jack Minnis, the head of the SNCC Research Department, put out a mimeographed newsletter, which he sent to the SDS people in Michigan. One of the newsletter’s had a paragraph about sugar and the Dominican Republic. That’s where I got my lead on the US invasion of the Dominican Republic.

Minnis actually picked up on the sugar industry as what was driving the US invasion of the Dominican Republic. Cuba, the largest supplier of sugar to the US was cut off after the Cuban Revolution. We needed sugar. The Dominican Republic was a replacement for Cuba. And Minnis found some key people in the Johnson administration that helped trigger my whole power research project.

I took that research and — actually, the story is interesting.

Please, tell the story!

There was a guy who was involved in the Dominican Republic intervention named Fred Goff. Fred and I were two of the three founders of NACLA. This happened because I wrote a paper on the Dominican intervention and the sugar industry. A friend of mine went to a peace conference in Cleveland and took the paper with him.

Fred Goff, who had just gotten back from the Dominican Republic, was at the conference. He had played a nefarious role in the Dominican Republic, setting up a “Free Election Committee” — an outfit chaired by Norman Thomas, the famous US socialist leader — to rubber-stamp the US invasion.

Fred read my paper and thought it was very significant. This is why research is so important, by the way. Fred hadn’t understood the power structure of the US and how it was related to the invasion of the Dominican Republic. That’s what I described in the paper that I wrote.

Fred immediately came to Ann Arbor, and we met. He walked into the living room of a friend of ours. Fred was as straight as an arrow, wearing a tie and dress shirt. I thought right away, “He’s CIA.” I asked him one question: “Who is Sacha Volman?,” who I suspected was a top CIA agent in the Dominican Republic. Fred laughed. Sacha Volman was his contact person when he first arrived there in the Dominican Republic and played a major role in the Free Election Committee.

We immediately hit it off. And I said to Fred, “Look, the American people know nothing about what’s going on in Latin America and how the United States is dominating the region. We have to educate them enough so that they’ll take action and push the US away from its dominating role.” And he said, “I’m with you, Mike.”

So that led to the founding of NACLA, literally!

Can you talk more about the role of power research in the early years of NACLA?

It was really central. The analysis of the Dominican Republic invasion that we developed was eye-opening. All of us were quite active around the Vietnam War. People wanted an analysis of what was going on! Why were things happening? Why was the US doing what it was doing?

It wasn’t just about anti-communism or trickery or morality. It wasn’t by chance. There was rhyme and reason to it all, and power structure research gave you a way of understanding why the US government did what it did.

Fred said we should do this kind of research for the rest of Latin America. We have to understand how the United States is involved in Brazil and Chile and Peru and Mexico, and how the corporate power structure has generated the interventions and modes of domination that existed between the US and those countries. So we founded NACLA with the aim of uncovering the power relations that directed and ruled US policy toward Latin America.

We also wanted to create an independent institutional structure outside of academia that could sustain this type of work by employing full-time workers.

What role did NACLA play in popularizing power research in the 1960s and 1970s?

We were constantly trying to give people tools they needed to do research and take action. That was the intention. For example, one of our members, Mike Klare, did a detailed analysis on chemical and biological warfare research at universities. We revealed the exact locations where this kind of horrible work was going on, showing that it was happening at major university campuses where liberal ideology was deeply entrenched. Most people didn’t know that this was happening and the outrage drove students and professors to take strong, direct action.

The research gave people a focus. It gave them a target, a place to direct their opposition work and to protest and demonstrate. We ended up doing a whole series on the military-industrial complex and university contracting work. Again, this helped people understand that the war machine existed on their campus and in their community, and that it was within their ability — and responsibility — to do something about it. In fact, a lot of this research led to 1968 demonstrations at Columbia University.

Were there other groups doing power research that you connected to or collaborated with?

We were in constant contact with others. We worked with the Africa Research Group, which tried to do something similar. A guy named Danny Schechter, a very important journalist, was a leader of that group along with several others. But it wasn’t as successful as NACLA and didn’t last as long.

We worked closely with the anti-apartheid movement. Together, we uncovered US bank loans to South Africa. Apartheid was not something mystical. US banks were financing the apartheid system. We published a study, which was widely circulated, that detailed the US bank loans to South Africa. It showed how big the loans were and which banks were involved. We published all of it, and several faith-based groups, especially the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility (ICCR), spearheaded the struggle.

Some of that information was actually out there already. SDS staged an anti-apartheid action at Chase Bank around 1965, but we wanted to promote more activity, so we put together the pamphlet.

There was also NARMIC (National Action/Research on the Military-Industrial Complex), which did very important work on the military-industrial complex. We worked with them, although it was harder to stay in contact because they were based in Philadelphia. We didn’t have the internet or Zoom back then. Everything was done by phone or in person. Still, we interacted with them a lot, holding many meetings and seminars and sharing ideas on methodology.

Then there was the American Friends Service Committee. They were very important in the religious community. As I indicated, we also did a lot of work with the ICCR. They worked on corporate resolutions, and we provided information for some of their first resolutions. In fact, one of their earliest resolutions was on the Dominican Republic. We provided a lot of material they used to push for resolutions at corporate meetings opposing US activities in the Dominican Republic, especially with regard to labor practices.

We worked with others too. We actually had a conference in New England — I think it was in Boston, in 1967 or 1968 — where we tried to coordinate research among a bunch of different organizations. We wanted to create a consortium of power structure research groups. It didn’t lead to much, but it did result in some cross-fertilization and interaction.

We also worked with groups that were doing community power structure research. SDS did studies of a few communities through its Economic Research and Action Project (ERAP). SDS had a whole organizing program in ten cities, and they did power structure analysis in each city. Boston was included. An SDSer named Jill Hamburg especially did a lot of work on community power structures. We interacted with her quite a bit. She actually did a handbook on community power structure research.

Can you say more about the methodology guides and handbooks people were putting out?

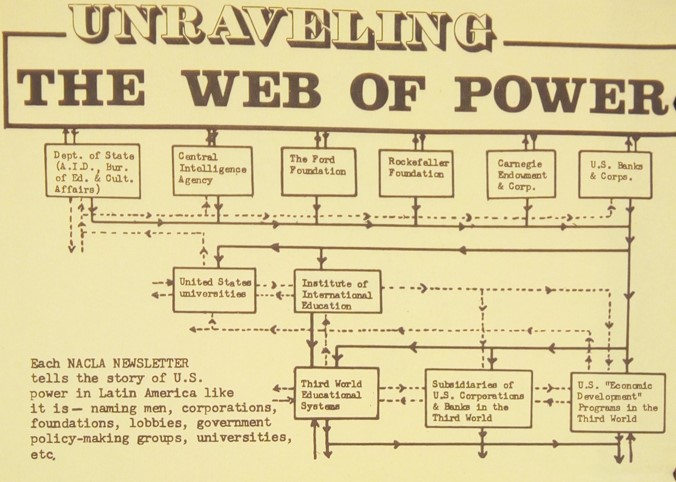

The handbooks were extremely important. We wanted to get our methodology to other people. We wanted to get the tools for power structure research into other peoples’ hands. That’s why NACLA published a Research Methodology Guide. It sold thousands of copies. It was all based on sources which are now largely outdated, but the idea was the same. Whether you use Moody’s back then or you use the internet today, you’re trying to uncover key power relationships. And you need to know the methodology and best tools to use.

We also did some power mapping for the protests at the Chicago Democratic National Convention in 1968. We knew there was going to be large demonstrations and a major confrontation in Chicago, and we expected the cops were going to be violent. I was there in Chicago in 1968.

Some of the organizers wanted a power map of the defense and military institutions in Chicago to support the demonstrations. So we did a whole analysis of all those institutions that was published in a special edition of an underground newspaper called the Rat. We did it in cooperation with others and it was handed out to people at the protests in Chicago.

We uncovered all kinds of things, including the location of the office of the Central Intelligence Agency, which was undercover. So there was a demonstration at that office. There were demonstrations all over Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention at places that were doing military research. We researched all kinds of ways for people to express their anger and revulsion with meaningful focus.

The question was: How do we take all the enormous anger that existed around the war, the draft, and civil rights and get people to focus that energy in a direction that can have some impact? We don’t want to just express feelings. Feelings are important, but mass movements, mass actions, and mass pressure is what creates change. And I think we created change. The movements of the 1960s were very successful in many ways, even if they weren’t completely successful.

“Who Rules Columbia?” and Doing Power Research in the 1960s and 1970s

You mentioned the Research Methodology Guide. Were there other examples when organizers picked up on your research methods and used them?

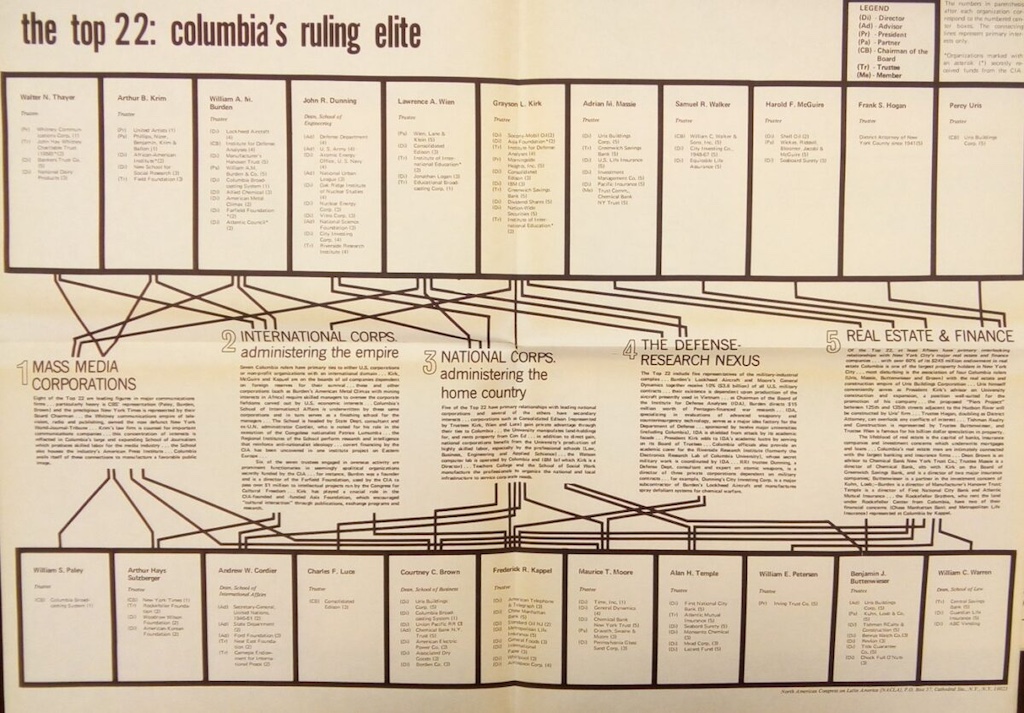

“Who Rules Columbia?” is probably the best example. We were close to SDS in New York, and SDS was at the forefront of the sit-ins and occupation at Columbia [University]. We recognized right away that a power structure analysis of Columbia would help. We wanted to research who controlled and ran Columbia and who the decision-makers were, all with the intention of exposing the true functions of the university and its impact on students and professors. We made it clear the school was being operated to serve the interests of wealthy and powerful business interests by training and channeling students to run their institutions.

So, we dissected it all. Very little past work on this had been done. We put together and designed a wonderful pamphlet and published it the day of the 1968 graduation. It sold many hundreds of copies and was distributed nationwide.

Other university campuses immediately grabbed onto it. We were in discussions with SDS chapters at Harvard and University of Chicago and other places about doing a similar mapping. I think at least eight or ten “Who Rules” studies came out afterward, and the methodology was very similar. Some of them were even better than what we did on Columbia.

Overall, there was a lot of motion on campuses then, and I think we helped by providing the methodology and tools for people to focus on the real centers of power on their campuses — the board of directors, their relationships, and why they were making the decisions they were.

Clearly not enough changed. The current generation of Palestine solidarity organizers at Columbia were able to produce some helpful research using very similar tools. Again, people want to understand why things are happening, not just that they’re happening. Power structure research gives people a way of analyzing and understanding what they’re up against and feeling more confident in what they’re doing and how they’re directing their energy and power.

Just to recap, who did rule Columbia?

There were real estate interests and banks, defense contractors, multinational companies, and other financial institutions. There was Con Edison, which has enormous interests in New York City and in recruiting labor for its operation. There were people from the RAND Corporation. There was Grayson Kirk, the president of the university, who was very close to the CIA, which operated freely throughout the campus.

I feel like “Who Rules Columbia?” really showed a way of looking at the university as a power structure that was interlocked with a wider network of corporate power. Can you talk more about what you were trying to accomplish with it?

For one, we tried to blow away the myth that the university was an institution for free thought. We tried to show that the university was a channel for labor that corporate power needs. That’s still true today. Universities are not founded in order to develop “thought.” Of course, they do research, but that research is extremely valuable for corporate profits and scientific needs of corporations and the military. Universities groom the people that corporations need — a cadre of people who can generate new ideas and keep the capitalist system dynamic and operating.

That’s what the university does. It’s a training center for private enterprise. The energy and creativity that the system needs comes out of universities. The military also understands this — that universities are essential for generating new ideas and technologies.

Of course, there’s “learning” that happens at universities. But the reason you have corporate elites joining and running the board of directors and donating money is with the aim of providing the feed stock, the ideas and personnel, that the system needs in order to grow and be vital.

Why was it important for the student movement to have this analysis?

Again, student protesters felt very emotional about the war and racism, but emotions only get you so far. We felt we needed an analysis to compliment the emotions and give people the power and focus to act.

Power structure research and analyses of power gives people a higher level of motivation to act. It gives them a specific set of targets for their energy and emotion, whether those be corporate headquarters or a corporate resolution or whatever. How do you express your horror and your repulsion in ways that can affect what’s going on? A good power structure analysis provides some of that capability.

What kind of influence did “Who Rules Colombia?” have beyond Colombia?

It had an enormous impact. I think it’s still having an impact.

Didn’t other student movements start mapping their own campus power structures after it?

There were countless others — including Harvard, which is one of the more famous studies — that mapped the power structures. In my opinion, we unmasked what the university was really based on. It wasn’t based on lofty ideals. The underlying force which drove and directed the university and its decision-making was making money and supporting the system by supplying it with labor and ideas and new technology. That’s the purpose of the university. People started to understand that they were a cog in that wheel.

But to understand that, people had to know what forces were controlling their university. And all the power structure analysis of the various universities came up with the same conclusion: corporate power determines what’s going on at universities and shapes universities around its own needs and interests.

How did you do power research in the 1960s and 1970s? Can you talk about the sources you used and the nuts and bolts of doing this research back then?

The secret was the business library. One day, Tom Hayden told me to go check out the University of Michigan’s business library. I had never been there and in fact, I had an actual revulsion to going to the business library because I knew it was pro-business! But he insisted I should go.

Well, I went to the business library, and a whole world opened up. It was a world of systematic information on corporations, politics, and economics. Remember, there was no web. But at the business library, I found directories filled with information that previously I only could speculate about. There was Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s. I found information on boards of directors. There were these directories that systematically organized the material on every US public company and some private companies as well.

“My God,” I said to myself. “This is unbelievable!” It completely changed my life. I spent months in the business library, going through everything and taking notes.

I learned about all the sources. In fact, our methodology was built around understanding those sources. It was similar to what [Karl] Marx did in the Reading Room in the British Museum in London, going through original material and taking notes. That’s what we had to do. When I did my research on the Dominican Republic, I did it all at the business library.

To understand the corporate power structure and understand American business, you have to use business sources. You need to study and use the material generated by the business community to analyze how a company or an industry is operating. You have to dissect and understand that material to develop a strategy.

Can you say more, specifically, about what you mean by “business sources”?

By “business sources,” I mean everything that business generates, whether its printed business publications before or online data sources today. Wall Street generates an enormous amount of data to help guide investment decisions. Since the 1930s, the government has required disclosures to provide transparency and even out the investment playing field. Most of this information is public, but it was hard to access back then due to limited outlets or high prices.

But business libraries, and now the internet, have a plethora of well-organized, free data. It’s just a question of how you use it. Actually, that’s what LittleSis has helped so much with — putting the data together and making it systematically usable.

We didn’t have an excess of data readily available in the 1960s or 1970s. We had to do the research in the business library or from press clippings and books. But our task was still the same as it is today: How do you take the information that business puts out and make sense of it from a power structure point of view? How do you analyze and dissect it to understand how corporate power works and why it works the way it does, both in the economic and political worlds.

The whole methodology has not really changed, but the online source material is so much easier to access now — and maybe even harder to analyze, because the amount is so overwhelming.

Labor, Locker Associates, and Corporate Campaigns in the 1980s–1990s

Toward the late 1970s, you decided to form your research firm, Locker Associates. Can you talk about that?

I left NACLA in 1973 after the horrific coup in Chile. At that point, I wanted to move beyond just focusing on Latin America work and do power structure research more broadly. I founded another organization called Corporate Data Exchange with Steve Abrecht, a wonderful guy and fantastic researcher who was also in NACLA. Steve has since passed away.

We decided to produce directories on who owns American corporations. There was interest in this kind of information from church groups doing corporate resolutions, labor unions doing organizing drives, and community groups challenging real estate and financial interests. Our idea was that libraries and other institutions would buy the directories and we would provide movement groups the information for free.

We produced five of these directories on who owned the largest US companies. We did one on banking and financial institutions, another on transportation, another on agribusiness, another on energy, and finally one on the Fortune 500. We wanted to find out who owned the stock of the largest companies in each of these industries.

We went to Washington, DC, and collected all the filings on stock ownership from various government agencies. We recorded information from filings at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). We searched indexes of the business press, like Forbes and Fortune and searched biographical material on important individuals and families that often included data on stock ownership.

Most importantly, we discovered an extremely valuable but expensive source that collected systematic data on stock ownership in publicly traded companies, a source that most movement researchers did not know about or couldn’t afford.

We catalogued all of the data from these sources and fed it into the main frame computer at Columbia University. We had a custom program developed by a movement programmer, Peter Brooks, that generated the stock ownership profiles of each company, ranking the holdings by size and cross indexing all the owners. That’s what we published. It took an enormous effort to produce.

We discovered all kinds of stunning things. We found that a handful of financial institutions controlled and had a large influence over most of the companies we were investigating. Today it’s even more concentrated by firms like BlackRock and Vanguard and Fidelity.

We got some interest and some press, but ultimately it wasn’t sustainable. We had no source of income. So we decided to do some contracting work, and we looked toward the labor movement because we felt they could use our research capacity in organizing drives.

How did that all begin — your entry into doing research for the labor movement?

It’s actually a great story. We finally ran into one labor leader who was interested. He had an enormous campaign going on against a company called J.P. Stevens. It was one of the most important organizing campaigns in recent history.

Was that the Norma Rae campaign?

Yeah! So Jack Sheinkman was the head of the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU). He was a great labor leader, primarily because he was willing to take risks. He heard about our research and he called us.

Sheinkman told us he had a problem. He had eight or ten J.P. Stevens plants with union representation, but they couldn’t get a contract. Sound familiar? Hello, Starbucks and Amazon! It hasn’t changed a bit. It’s gotten worse, in fact.

Anyway, he asked if we could look at J.P. Stevens and find a way to get them to stop stalling and get them to the table to negotiate a contract. He had bet the union’s future on this organizing drive. The company had moved its plants to the South and broke the union. An intense boycott of Stevens’s products did not put enough pressure on management, so Sheinkman had to find another way.

So we looked at J.P. Stevens. We looked at the board directors, who’s financing the company, their major customers and major suppliers, and so on. And bingo — found a major insurance company that was largely financing J.P. Steven’s debt.

What happened after that?

I went back to Jack and told him that this insurance company has tremendous influence with J.P. Stevens. Jack actually knew the insurance company’s chairman. I asked how much ACTWU and the AFL-CIO (American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations) had invested with that insurance company. It was hundreds of millions of dollars.

So Jack called the head of the insurance company and told them he needed to meet with J.P. Stevens and get them to settle the contract, or that the union would — hint, hint — have to reconsider where its money was invested.

Well, they got the meeting, and eventually they got a contract. So the interlocking relations we uncovered at J.P. Stevens were crucial for winning the organizing campaign.

We got $5,000 for this. That’s what Jack paid us. But it was our first union research contract. We worked with Ray Rogers on this too. Many of the research people from ACTWU actually went on to lead the corporate campaign work in several other unions.

What do you think explains the rise of corporate campaigns within the US labor movement beginning in the 1980s?

Unions were starting to decline in power, and the corporate campaign strategy gave them an added tool and more power to get what they wanted, which was usually union representation and a good contract.

Of course, this isn’t a substitute for organizing. You can’t do a corporate campaign without organizing the base and framing the struggle in social justice terms. Some people have accused us of just wanting to have corporate campaigns. No, that’s not what we want! We said this was an additional tool or additional mechanism that you can use to influence corporate policy.

Increasingly, labor unions started to catch on. The turning point was the J.P. Stevens campaign.

Have you read the book Death of a Thousand Cuts? It’s a seminal book on power structure research and corporate campaigns in the US.

I think you mentioned it to me once, but I haven’t read it.

You have to read it! It goes through how and why corporate campaigns developed within the union movement. Incidentally, the author, Jarol Manheim, is against them, but it’s still a very important book. Actually, he mentions in the book that Michael Locker in New York City was the leading advocate of corporate campaigns in the United States. So I get a lot of credit, which is wonderful.

I’m being emphatic. Everybody at LittleSis should read it.

Thanks. I’ll plug that book in the interview. Going back to why you decided to form Locker Associates in the 1980s. Can you take us through how and why that started?

We stopped focusing on compiling corporate data around 1981, and Steve Abrecht and I founded Locker-Abrecht Associates, which was the first name of the company. Steve left later on and joined the Communication Workers of America (CWA). Then he then went all the way to the top of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), running its corporate campaign operation.

Anyways, we decided that we really had to do consulting work. We couldn’t do publishing and survive. We wanted to remain independent. I was offered several union jobs, and so was Steve, and he eventually took one, as I mentioned. I wasn’t interested in working inside a large bureaucracy. I find that very difficult and limiting. I’m not blaming anybody who does it, but it just wasn’t for me.

I wanted to have an independent company that could be more flexible and more political. So we formed Locker-Abrecht Associates, and we went out to find contracts with unions. And we found them. That gave us the sustenance to do the work I’ve been doing since 1982.

What were some other movements happening in the 1980s and 1990s that you were involved with and where power research had a role?

Definitely Central America solidarity work. A lot around El Salvador. NACLA did a lot of work around identifying corporations and financial institutions involved in US policy toward Central America.

But I was mostly doing labor consulting at that point. I was working almost full time with the Steel Workers and helping them restructure the steel industry throughout the US and Canada. You have to understand that corporate campaigns are the opposite side of the coin of corporate restructuring. When you restructure a company, you basically analyze it just the way you analyze a corporate campaign. What do the key elements of power want? How do you reach them? How do you put it all together?

In the case of corporate restructuring, you have to make a deal, and the labor unions have to be involved. All the skills I learned in doing power structure research were very applicable there. Power research is actually very apropos for doing investment banking. It sounds strange, but it’s absolutely true. Again, I have no formal education in power structure research or in finance or the steel industry. I learned it all by myself, by just doing it, and by learning from people who knew how to do it.

So we also did a lot of corporate campaigns in the 1980s and 1990s. The union movement, particularly the United Steelworkers, a wonderful union that I worked very closely with for twenty-five years — I ended up doing a lot of employee buyouts for them as our work evolved. The whole idea that maybe we should buy companies for our members through employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) made a lot of sense to the union.

Did you work with Staughton Lynd at all?

Oh yeah, I worked with Staughton. He was in SDS. He was involved in Youngstown, Ohio, in particular. He was a wonderful labor lawyer, too radical for a lot of unions. He remained very independent and clear minded. Both he and his wife, Alice, were just wonderful people that advocated transformative initiatives.

Actually, his parents wrote Middletown. Do you know the book?

Yes, I’m familiar with it.

Staughton understood power structure research because of his parents. Actually, maybe Middletown was one of the other books that Tom Hayden told me to read!

What else were you focused on in the 1980s and 1990s?

We did a lot of research on pension funds and the power of workers’ money within the US power structure. There’s a very important book, The North Will Rise Again: Pensions, Politics and Power in the 1980s, by Jeremy Rifkin and Randy Barber. It looked at how pension money could be used to create jobs and revitalize the American economy for workers.

The whole idea that American worker pension money is used against workers was a stunning insight. It’s still true today, even more so than when they wrote that book. Anti-union institutions have taken the money that American workers have earned and used it for the purpose of improving their profitability and undermining worker power. So it’s a very important concept that gets at a contradiction in the capitalist system.

By the way, Jack Sheinkman, who was also on the board of the Industrial Union Department of the AFL-CIO, had us do a study on pension investments to show how the money was actually being used. We looked at pension investments in companies that were union busters or nonunion corporations or firms that had discrimination suits filed against them. We did a study of one hundred large pension funds and mapped out their holdings. And lo and behold, they were being used for all kinds of anti-working-class purposes.

What happened to that study?

The AFL-CIO dropped it like a hot potato. Nobody wanted to deal with it. The problem is the American legal system has made control of pensions a fiduciary responsibility. If you don’t follow your fiduciary responsibility, you can get sued. So if you’re on the board of an insurance company and you advocate against investing in a corporation because it’s anti-union, you’re told that you’re really violating your fiduciary duty, because your primary fiduciary duty in managing pensions is to make money and not to do “social investing.”

In fact, the whole “social investing” thing came out of this! I was involved in its development. I was at some early meetings of money managers who wanted to have a social screen. Now this has become a whole world of investments. I encouraged it. I thought it had some legs. But it can also be greenwashing.

Most importantly, the one thing they definitely didn’t want to screen was labor relations. That really bothered me. I remember, in the early meetings, we set up an institution to help people with the methodology for screening. I kept advocating for a screen on good or bad labor relations. They rejected that, and it’s mostly rejected to this day.

They’ll do environment. They’ll do civil rights. They’ll even do human rights, mostly for workers abroad. But most won’t do labor rights. You know why? Because there’s a contradiction between capital and labor. They don’t want to promote the interests of labor. They want to promote the interest of capital. That’s putting it bluntly, but that’s largely what happens.

Lessons From a Life of Power Research

Stepping back, what has evolved or changed the most about power research over the past six decades that you’ve been doing this work?

What’s changed? People are using it a lot more! When we started out, it was an oddity. It wasn’t something that most movement people did. But now, unions, environmental groups, community organizations, nonprofits, advocacy groups, political campaigns — they’re all using it. This is especially true today in the labor movement, though it’s not universal. There are several unions that still don’t use power research.

So it’s become a widely accepted technique or tool for developing strategy and tactics. It’s so important to understand who and what you’re up against. If you don’t really realize who you’re up against and what their strengths and weaknesses are, your chances of winning are really diminished.

If you want to plot an effective strategy and be able to judge whether you’re making headway — in other words, understand whether you’re winning or losing — it makes a big difference to be able to really understand who you’re up against.

Today you have terrific organizations like LittleSis, which is phenomenal! We had no organization like that. There were a couple of groups that tried to do it, but they weren’t really devoted to power structure research in the way that I think people are devoted to it now, with power research in and of itself seen as an important component of political work. That just wasn’t true forty years ago.

Another big change is that the Right is also using power structure research. [Donald] Trump’s forces have used it. You have a political spectrum, both left and right, which are using this technique, not just progressive forces, but also more reactionary and more conservative forces.

Are there limits to power research? How should movements approach using power research in a reasonable way?

Organizing people or organizing workers is fundamental to any campaign. Power structure research is a tool within that context. It doesn’t replace or override organizing. It’s one tool that organizers and campaign people can use to augment their power. It doesn’t replace the fundamental need to do good, basic on-the-ground organizing work.

People who think there’s some technician who will figure out the power relations and they can win the campaign — well, I don’t think that’s true. I think you win campaigns because you mobilize and organize people. You create power through the action of people. Power structure research is a mechanism by which you can better hone your strategy and tactics. You can better pick out your targets and your actions, and you can escalate more carefully or more efficiently. But it does not replace basic organizing, and it never will.

Campaign practitioners who mechanically use power research are largely ineffective. Without a social justice framework, it’s extremely hard to gather enough power to win.

How can the labor movement today make the best use of power research?

If you’re organizing a company or plant or workplace, knowing the power relations that control that workplace is essential for understanding how to pressure the boss and win your organizing effort. Research along these lines also allows you to identify potential allies, a key component for building sufficient power to win.

That’s what amazed me about power research. When I and others brought this idea to unions, a lot of them said, “What do we need this for? Why do we have to know who owns or finances a company?” It was striking to me that people didn’t have an understanding of why those elements were important.

Again, they’re not silver bullets, but they give you insight about who you’re dealing with, what you’re up against, and, most importantly, it reveals key targets to pressure. If you’re organizing and you’re trying to figure out a strategy to effectively change a company’s policy to win union recognition or win a contract, it just seemed rudimentary to me that you’d have to know these things. A lot of unions today now appreciate that and have departments that are devoted to mapping power relations.

Are there any limits or downsides to corporate campaigns?

There is a danger that you can lean on it too much and not do the basic fundamental organizing of people, which is where power is really located.

Organizing means trying to develop and utilize power in order to change policy and decision-making. You can’t do that by just identifying who controls or operates the entity you’re organizing against. You have to have a powerful force, which is what people represent, in order to change the situation. If you don’t have that, if you don’t have enough power, it won’t be enough to really change the situation. This often means forming alliances or coalitions with others to build sufficient power, and power structure analysis helps identify potential allies and supports. Again, the social justice framework is crucial.

But you need people in motion. You need that militancy to stop the wheels from turning. You need to throw a wrench into the system so that people understand how much power they really have. A lot of times, companies don’t even realize how much power workers have. And often workers don’t realize how much power they have.

Unions, unfortunately, have not moved in this direction. They’ve moved away from it. They focus mostly on servicing their members, providing benefits, and so on. This is not unimportant, but if you just rely on providing a pension plan or a health plan, and you don’t rely on exercising the power you have of stopping or threatening to stop the operation by withdrawing your labor, you will weaken your position and lose your power. That’s what’s happened.

What are the big lessons you’ve learned from your decades of doing power research that you think are important to pass on to new people?

First and foremost, you must center any campaign around social justice issues, not just demands. In other words, to gather meaningful support, both among the workers directly involved and the wider community indirectly involved, you need to carefully wrap your specific demands around broad social justice concerns.

A fabulous campaigner, Ron Carver, made me aware of this. For instance, if you seek higher wages, you need to frame your demand around the poor living conditions created by low wages. It’s not so much the right to higher wages, it’s more the impact of lower wages on people’s lives. Zohran Mamdani did that so well in his recent New York City mayoral campaign.

Next, you need to pay close attention to the details when doing power structure research. The forensic part of research is very important and also very difficult. That’s why the more advanced techniques we’ve developed for tracking and formalizing the information are hard to organize and make sense of. But without the details, you really don’t have a good practical analysis for developing a powerful analysis and effective tactics.

You have to weave between the big picture and the details and back out to the big picture. You need to constantly go back and forth between the forest and the trees. And if you have a hunch, you have to test the idea with more information to see if it makes sense. Then you go back out to the general and see if you have an analysis that makes sense. So there’s this back-and-forth process, which takes time.

Another thing I’ve learned is that the research for a corporate campaign can take time. Understanding the power elite is not going to happen in a day or two. It takes a significant amount of time to really understand what’s going on with power. Often the people who retain you to do the work, or the department you work in, put unrealistic demands on you. They want an answer in a day or two.

Well, I got news for you. You can get a general idea in a day or two, but if you really want an analysis that makes sense and is going to help you organize a campaign and shape your tactics and strategy down the correct road, then that takes time. You have to probe, you have to interview, you have to cross tabulate information.

I’ve also learned that the international aspect is very important. We’ve learned that trying to internationalize — well, first regionalize, nationalize, and then internationalize — a campaign through research and solidarity networks is very important. The relationships we find through power structure research go way beyond just the immediate company and into a much larger and international context.

Also, it’s important to constantly be learning news sources. People tend to become lazy and use the same sources of information over and over again. They start to rely on those sources and don’t experiment enough with new sources. But sources are always evolving, and they’re very accessible with the internet. You have to ferret out new sources continually and see what they add to the analysis.

Is there an example where you’ve used a new source that has helped?

Clearly AI has changed the game. The incredible power of new search engines with their ability to uncover hidden relationships is redefining research. Of course, you must carefully vet the search results for obvious reasons — you can’t afford to make a charge that proves false or unsustainable since credibility is the basis of trust.

WhaleWisdom is very good. I actually didn’t know about it until we learned about it from LittleSis. There’s so much out there, it’s hard to keep track of everything.

The other thing I would say is we need more methodology guides. We need more material that helps people learn how to do this on their own, as opposed to just outsourcing this work to others. There’s nothing like having research people internal to a campaign and to be able to constantly have research people and action people interacting to develop and hone strategy and tactics through that interaction. That’s a very valuable aspect to organizing and campaigning. When you’re embedded within the campaign and not outside the campaign, there’s a different dynamic in how the research is used and employed.

Looking back on your life and your long career doing power research, what are your reflections on what it’s all meant to you?

My interest in social justice is the overriding theme. If you want to do this, you really need to have a general outrage about injustice, whether that’s around inequality, health care, housing, labor, whatever. It’s all grouped around what I would call social justice. The hard part is finding a way to use your skills and talents and also make a little bit of money to sustain yourself in the process of promoting social justice. That’s very hard.

We formed NACLA not just because we wanted to do research into US-Latin American relations. We wanted to provide a home for ourselves, an institution that would give us the kind of economic and social support we needed to carry out this kind of work on a long-term basis.

So finding a home is important. It has to be a conscious effort. You can find a home working for the labor movement, but when you join a large organization, you also tend to compromise. That’s why I didn’t join a large organization. I was offered several positions in large unions, but I didn’t take them. I always built my own organization or worked with independent people who are building an organization outside of a larger bureaucratic structure.

Why? I didn’t want to be conflicted. There’s an inevitable conflict — whether you’re a professor or you’re working in the research department of a union or you’re in a government agency — when you’re in a big institution. There’s a lot of compromise to maintain your position and a lot of politics involved. And I’m not wedded to that. Never have been.

How do you feel about dedicating your life to the movement through power research? How has it enriched your life?

I’m dedicated, but that doesn’t mean I haven’t made some compromises in my life in order to sustain myself. It’s impossible to live a pure political reality. You’ll be a hermit. You’ll be a seminarian. You won’t be able to relate to the world. So there are compromises.

The question is, how big are the compromises, and can you stay true to maintaining your purpose of fighting and advocating for social justice? That’s a major struggle. Most people compromise. They go into an occupational structure where they become part of the society in ways that are less antagonistic and more cooperative.

I think outrage is a very important component. When I realized the government was lying to me about the Vietnam War, that was a very politically important thing. I couldn’t trust the government. My government was lying and it continues to lie. That outrage is very, very important as a motivating force.

You’ve been at this for decades. Any advice on committing to movement research for the long term?

The long-term survival of somebody doing this kind of work and not burning out or getting distracted or bought out, lies in your original level of commitment and political motivation. I come out of a period — the 1960s and 1970s, the civil rights and Vietnam antiwar movements — that’s hard to replicate. The United States government was so clearly duplicitous and compromised. It has to be deep inside of you, the thing that originally sparks or ignites your commitment to doing this kind of work, or you won’t continue to do it.

I think the people working around Palestine today have had that kind of experience. I don’t think you stimulate that level of commitment through seminars and reading. It’s about emotion, though the analysis you develop to make sense of that emotion is really critical. It’s a complicated process.

I think emotions play a vital and strategic role in how you form your life. The emotional experiences I went through when I was younger formed me and continue to form me today. I probably won’t see the social change that I want to see in my lifetime, but I want to continue to do as much as I can toward making that happen.

Finally, I think it’s important to point out that fighting individual companies is not the same as fighting against the system. While we need to focus on specific corporate injustices, I think we have to better understand and confront the broader system within which companies operate.

For example, the denial of basic workers’ rights is endemic. It’s something that exists throughout our society. It’s centered in the business community but receives strong, much needed support from the media, educational institutions, political parties, nonprofits, and faith-based organizations. Company policies and practices help shape the environment, but they strongly rely on legal and governmental practices to justify, reinforce, and protect their decision-making power.

In other words, if we really want to change things we must find effective ways to change the system and all its assumptions — and this means confronting the power structure that controls and benefits most from the current system.