My Life as a “Terrorist”

Historian Steve Fraser looks back on the strange experience in 1969 when he and fellow New Leftists were accused of plotting to blow up Philadelphia’s Liberty Bell.

What is it like to face long-term incarceration for a crime of “terrorism” you didn’t commit? Historian Steve Fraser recounts his strange experience of being falsely accused of a plot to blow up the Liberty Bell. (Henri Bureau / Sygma / Corbis / VCG via Getty Images)

Political criminality might be organized into a hierarchy ranging from not all that bad to really bad. Acts of civil disobedience would rank near the bottom, or even escape censure entirely as “crimes” against injustice. Treason would probably come first. Terrorism could be a close second. Frequency correlates inversely with gravity: plenty of arrests for defying unjust laws, very few for plotting to blow things up. At least that used to be the case.

Nowadays, the old order is in disarray. Roughly half the population would qualify for indictment as terrorists by the powers that be. Most of them have not even stooped to commit a lowly act of civil disobedience — all they had to do was show up at a “No Kings” demonstration, or denounce Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents for behaving like Nazis, or picket an immigrant detention center, or, even more innocuously, claim a right to free speech. Even ranks of the most respectable — say, elected officials — are not immune to being branded terrorists.

Times have changed. In April 1969, I was arrested, along with a few friends, for conspiring to blow up the Liberty Bell, which happened to be pretty close to where I was living in Philadelphia.

So as not to keep the reader in suspense, let me say here: I didn’t do it, nor did my friends. But the local police, the FBI, and the Justice Department said I did. That I’m not writing this from a jail cell is in part thanks to a constitutional order then still intact enough to protect my civil liberties, something we can be far less certain about today.

Looking back at that alleged bomb plot conspiracy case raises a few questions: Why did the government feel compelled to cook up the terrorism accusation back then, and why again now? What caused right-wing and liberal political circles to collaborate in conspiracy-mongering in the City of Brotherly Love and elsewhere during the sixties, and what’s become of that relationship today? If terrorism was once an exotic, repugnant form of political criminality, what caused today’s inflation of dishonors, so that almost anybody may find him- or herself in its shade? Does a crescendo of terrorism accusations signal a crisis of the old order? Does the appearance of a startling movie, One Battle After Another, suggest a strange mood, half haunted by the specter of fascist-like sadism and state terrorism, half a melancholy, even sentimental lament for the futility of a righteous terrorism?

First of all, though, what did it feel like to face long-term incarceration for a crime you not only didn’t commit, but was alien to your political and moral beliefs? To answer that, we must visit the scene of the “crime.”

The Action

On April 9, there was a knock on the door of my West Philadelphia apartment. A half dozen or so members of the city’s police force — members of the Civil Disobedience Squad, known colloquially as the “Red Squad” — marched in, search warrant in hand. Within minutes, before the squad had even begun to search, there was a second knock on the door. Channel 3 KYW-TV, the local NBC affiliate station, came in to film the proceedings. Presumably they were tipped off in advance, but who knows — maybe they just got lucky cruising the neighborhood for hot news.

Traipsing through the large apartment several of us lived in, the squad came up empty for a while. The warrant empowered them to search for explosives. Finally, they found them in the kitchen, stowed in and under the refrigerator — an odd place to stow away incendiaries, but then again what isn’t an odd place for doing that?

Here’s what they “found”: an eight inch can of Dupont rifle powder, three six-inch-by-three-quarter inch outside diameter pipes, each equipped with a hole bored in the center of the pipe, six metal pipe caps, a ten ounce candy can labeled “Olde English Tavenders Fruit Flavored Drops” that contained a plastic explosive known as C-4, and about a six-inch length of red-orange dynamite fuse.

Serious evidence of evil intent: C-4 in particular is a potent military explosive capable of doing enormous damage. So I was arrested along with three others, charged with violating two state laws prohibiting possession and conspiracy to possess explosives with intent to use, as well as two city ordinances outlawing possession and storage of explosives with intent to use. Conviction carried long jail terms. Charges against two of those arrested were soon dropped, as they didn’t live in the apartment but had the misfortune to be visiting that day. I wasn’t so lucky.

Admittedly, this wasn’t my first rodeo, as they say. I’d been arrested before: in Long Beach, Long Island, for sitting in against housing discrimination; down in Mississippi during the Freedom Summer of 1964 for fighting Jim Crow; in Cambridge, Maryland, for trying to organize migrant workers; in Congress for declaiming against a House Un-American Activities Committee hearing; and so on. But this was different.

First of all, in these other instances I knew, or knew there was a good likelihood, that I’d be arrested. This time, I didn’t have a clue. And then there was the gravity of the charges. They were grave enough that my grandmother, who happened to live outside Philadelphia, fainted when she saw me on the TV news, shackled and being loaded into a paddy wagon. Grave enough that my uncle, who also lived near the city, didn’t speak to me for the next twenty years. As for me, I was simultaneously calm and panicked, oddly composed while fully shocked.

Right away I lost my glasses, which if you’re pretty nearsighted is terribly disorienting and added to my growing feeling of helplessness. Lacking a lawyer, one was assigned me by Legal Aid. He looked about as old as me, twenty-three, or younger, which was not reassuring (though he turned out to be a terrific lawyer). I had been in some creepy jails (one in Starkville, Mississippi, was actually underground), but the Philadelphia Roundhouse was a more fearsome fortress of disconcerting modernist design, encircled by a concrete wall, and notorious for its police brutality.

Waiting in the holding cell, inmates were treated to a “meal” that looked like the leavings of a nearby chemical plant, a platter of squiggling plastic which came in various shades of neon (could they be feeding us the C-4?). It added to my nausea and apparently to everyone else’s as we proceeded to dump the crap, uneaten, into the nearest garbage can.

Onboarded into the prison proper, I was assigned a cell by myself, which turned out to be a mixed blessing. Good to be alone and collect my thoughts. Bad because, not knowing the prison protocols, I was nearly decapitated when, at mealtime, the electrified cell door opened and then closed a nano second later; the phrase “better dead than fed” occurred to me.

Prison time lasted only a few days. Then I and my fellow “conspirator” were released on bail — $25,000, a lot in those days. However, while still in the hoosegow, I did have one visitor. I was enrolled at Temple University, although was not too regular an attendee. The dean of the Liberal Arts faculty came to see me in the Roundhouse. He wasn’t there to commiserate.

Instead, he wanted me out of the school with no fuss, no bother (for reasons to be gone into shortly). With the roster of my courses in hand (this was my senior year, although I’d been a senior several times, and for that matter a junior and sophomore several times at other colleges in the course of my peripatetic wanderings as an “outside agitator”), the dean assessed what I would minimally need to do to pass these courses. I later learned he then conferred with my professors to make sure they were on board. Soon enough, I had graduated (although I never received my printed diploma which to this day seems to me both unfair yet deserving).

Absurd, one might say. And there were elements of both incredible naivete and surreal absurdity about the whole affair. Like, for a long time afterward, I kept thinking that I had actually seen the candy can full of plastique in my icebox. But I couldn’t’ have. We were all students, poor as we could be, so there was never much in the icebox; candy, with or without plastique, would have been hard to miss. Plus, had there been a can of candy, we would have eaten it.

Then there was the police raid itself. As “New Leftists” we considered ourselves politically savvy, especially about the machinations of the state and its police forces. Yet it never occurred to any of us to wonder why a very long tractor trailer with no cab attached had been parked outside our apartment building for at least two weeks prior to the raid. Duh?

Dumb, hallucinatory, scared, yet up to the challenge. All during the squad’s “search” I had kept up a steady commentary for the TV cameras (later edited out by the station) not only protesting our innocence, but about why the police were staging this frame-up. And I believe the reason I was able to maintain that degree of composure was because I profoundly believed in the movement that the local, and as it turned out, the national police sought to destroy. And still do. What was that about?

Why Us, Why Then?

We all belonged to Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Within that large and raucous family, our “faction,” if you will, was notably anti-capitalist and socialist-minded. Although campus based, it looked for allies off campus among working people. We called ourselves the SDS Labor Committee. This orientation would matter a great deal when it came time to decide on whom to plant explosives.

At the University of Pennsylvania, the SDS chapter had been particularly active in mobilizing opposition to the planned construction of something called the University City Science Center. Designed, among other things, to conduct war-related research, it naturally elicited anti–Vietnam War sentiment then at its height. It was to be built on the outskirts of the Penn campus. The center was not Penn’s alone, however, but the undertaking of a consortium of Philadelphia-area colleges. SDS and antiwar groups at other colleges were also angry about the project.

To add to the infuriation, the center was to be built on land contiguous to the city’s second-largest black ghetto, located in West Philadelphia. Urban removal would inevitably follow in an area of great poverty and lousy housing. Exacerbating that was a predatory process of real estate speculation of an especially odious kind. Philadelphia law allowed for something called “sheriff sales” or “sheriff auctions”: Homeowners (in this case largely black) could be deprived of their homes at bargain basement prices if they had put up their houses as collateral for consumer installment-plan payments they could no longer meet, say for a car or a refrigerator. The Science Center, years before it would open for business, had already become a real estate speculator’s wet dream: buy up properties at sheriff sale and realize enormous capital gains on resale.

Nor were these small-time predators. They included the city’s elite real estate and financial interests — who also, by the way, enjoyed an incestuous relationship with the Science Center consortium.

For example: the Gustave Amsterdam realty and investment group (inheritors of the old Greenfield family estate); William Day, president of the First Pennsylvania Bank (the city’s largest); Richardson Dilworth, president of the board of education, once the city’s mayor, scion of an old Social Register family with important banking connections of his own — all were represented on the board of trustees of the center itself and the University of Pennsylvania.

Organizing to stop the Science Center therefore conjoined opposition to the war in Vietnam with the struggle against black removal, inadequate and substandard housing, and the exploitative practices of powerful commercial interests.

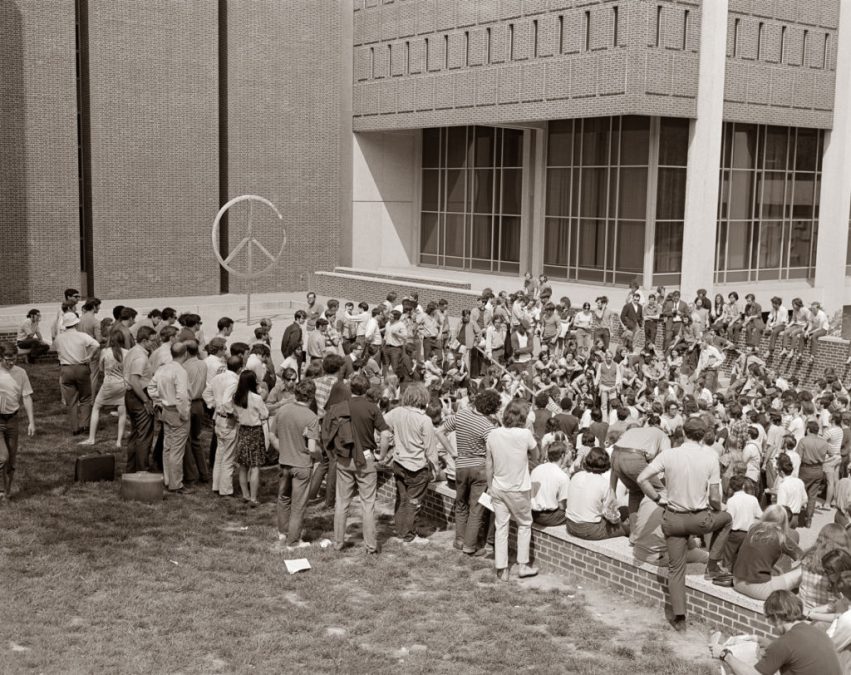

Late in February 1969, that sentiment took on palpable shape when students and members of the surrounding community occupied the Penn campus. Over several days , 1,500 students from various area colleges — Bryn Mawr, Swarthmore, Villanova, Temple, Haverford — joined the occupation, demanding that 1,200 low-rent housing units be built instead of the Science Center, that this construction would create, the occupiers argued, desperately needed new jobs, and that the work be financed at the expense of the corporate, real estate, and financial interests represented on the board of trustees at Penn.

Little of that was achieved by the occupation, which ended after several days. Commissions were established to investigate this and that, nothing more. Today, you can visit the Science Center and take a look at the peace symbol sculpture at the center of the Penn campus, the sole tangible memorial to the “Penn strike.” That was not quite all, however.

A movement born at the “Penn strike” to unite the concerns of students and the working poor grew substantially in the aftermath of the occupation. The Alliance for Jobs, Education, and Housing enlisted the energies of students and people from the black community, including the Black Panthers. It targeted the “sheriff sale” scam in particular, and more broadly the immiseration of people at the hands of those institutions for whom “sheriff sales” were part of a larger repertoire of capital accumulation.

In Philadelphia, the Panthers were mainly high school students. Organizing took place not only in the community, but in high schools, including some of the most prison-like in West and North Philadelphia. I remember “speaking” in one school (thanks to “guerrilla” infiltration, meaning thanks to our Panther collaborators) where the “classrooms” resembled chicken coops literally separated by wire mesh. Bedlam reigned. It was actually possible to loft sizable objects, even chairs, over the tops of these cages into neighboring classrooms. This happened.

We were mainly white middle-class college kids, the Panthers were the Panthers — what Antonio Gramsci might have identified as “organic intellectuals” who were fed up, acutely attuned to the heated racial politics of American foreign as well as domestic doings, and eager to enlighten and organize their communities. An odd coupling, yet for a time it functioned well. Too well, for some.

Bomb Plot Conspiracy Revisited

Flush with our recent success, we made a fatal miscalculation. The alliance and our SDS grouping tried to reproduce the Penn events at Temple University. Temple sits in the middle of the largest black ghetto in Philadelphia, North Philly. It had its own expansion plans. Real estate speculators were already busy, sheriff sales happening. Students from Temple had been present at the Penn occupation. The alliance made organizing forays into the white working-class neighborhoods of northeast Philadelphia. But we greatly overestimated our support and underestimated our enemies.

Today we may assume that political character assassination, including bogus accusations of terrorism, are the specialty of the Right. But weeks before the “Red Squad” raided our apartment, the first such libels came from the most respectable and powerful circles of the city’s liberal community. Richardson Dilworth, who had been a Democratic Party reform mayor in the 1950s before running the board of education — a man of impeccable genteel breeding, from a pedigreed Philadelphia family wired into the city’s financial elite — dropped the first bomb. He announced that SDSers were infesting the high schools, instructing students in how to make bombs, and plotting to blow up several schools.

To Dilworth’s right, the city’s police commissioner who would go on to become its most notorious mayor, Frank Rizzo, followed the liberal lead. He repeated Dilworth’s allegations and added, more colorfully, that SDS was distributing “Molotov cocktail pamphlets” to residents of the North Philadelphia ghetto. There was not a scintilla of evidence for any of this, as those interviewed in North Philadelphia testified.

Rizzo was an early premonition of Donald Trump. He traded in racism and machismo trying to appeal to white lower-middle-class and working-class people frightened by the upheavals, racial and otherwise, of the sixties. The commissioner had long since demonstrated a fanatical devotion to the politics of fear and conspiracy-mongering. Following the ghetto rebellion of 1964, he had framed the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) on charges of possessing dynamite; that was the end of SNCC in the city. He spent a couple of years chasing a largely phantom group called the Revolutionary Action Movement (consisting mainly of police informers) until he finished it off with a wild story about its plot to poison the Philly police by slipping cyanide into sandwiches served to officers on riot duty. In the Fall of 1967, the police commissioner applauded a bloody police riot against thousands of striking high school students. Soon enough, Rizzo would leverage his reputation as a guardian against the transgressions of the unwashed and unruly into two terms as Philadelphia’s mayor.

A man of no small political imagination, Frank Rizzo was, nonetheless, not the originator of what might be called state terrorism. Dilworth and his liberal conferees played the role of instigator. And they didn’t act alone. The “Red Squad” and Rizzo let it be known that the plot they had aborted was part of a larger “East Coast bomb plot conspiracy.” It was alleged to be headquartered in Boston and under investigation by the FBI. Later to be identified as the bureau’s COINTELPRO operation against radicals nationally (first conceived in the Dwight D. Eisenhower years and running through the John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson administrations), this broader left-wing scheme was to kick off, so the bureau explained, by exploding national monuments in Boston and Philadelphia. Hence the Liberty Bell, hence that mysterious tractor trailer parked for weeks outside our apartment.

Liberalism was once described as anarchism plus the police. This seems too simplistic, but it has a point. I never served time for this imaginary conspiracy, and that is thanks to a then-existing liberal-democratic judicial order. It was our word against the police’s, after all, and they had claimed they found the bombs, or the makings of them. True, the raid was sloppy — for example, at preliminary hearings the prosecution couldn’t explain why they had failed to take fingerprints from the bomb components. And our group had a long history of publicly condemning political terrorism. But gunpowder is gunpower, plastique is plastique, and the times, akin to today, were overripe with paranoia. Who knows what a jury would have concluded?

Enter conventional legal procedure. The case dragged on for a couple of years and was finally dropped because the prosecution refused to turn over to the defense the reasons for, and records of, its surveillance of our group, which the defense was entitled to under normal legal proceedings. (Through the Freedom of Information Act, I have the heavily redacted communications between Attorney General John Mitchell and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, in which they decide to refuse the judge’s order, presumably to protect the identities of their informers.)

Does the liberal order therefore deserve a reprieve? My grandmother fainted, my uncle and I were estranged. Even more important than that, the movement for Jobs, Housing, and Education was killed thanks to this same liberal order. The raid only happened once the attempt to spread the movement to Temple University and North Philadelphia had come up short, a moment of weakness thanks in part to the politics of fear purveyed not only by the local liberal establishment (including then Democratic mayor James Tate, a machine loyalist) but by the federal government.

Everybody is for jobs, housing, and education. Except not at the expense of powerful propertied interests, and not when voiced by a combustible social mixture crossing class and racial lines. Then even the most liberal elites may resort to the police.

Then and Now

The sixties were such a time. The liberal order was shaken. At such a moment, when to protect the status quo the state may turn to violence, it may also actually incite counterviolence — in a word, terrorism. Terrorism is the politics of the weak. It bespeaks not only outrage but a sense of helplessness about doing much to stop the outrageous, like the incineration of the Vietnamese people or the plight of the ghetto. And there were infamous instances of political terrorism during that time.

Not only then. Terrorism had been, for some time, a rare if indelible feature of the bloody history of capitalism in America. At the turn of the twentieth century, small anarchist groupings and others tried blowing up leading businessmen and political figures, in something they described as “propaganda of the deed.” There was, however, a prequel to these bloody-minded “deeds.” Violence was regularly being meted out by private corporate security forces (Pinkertons and hired thugs), local police, as well as state and federal militias against striking workers and many others engaged in protest against the inhumanity of capitalism. People were jailed, deported, and even executed.

Back then and since, liberals have decried the violation of civil liberties that often occasioned these events. That is worthy and sometimes courageous. Today, liberals as well as left-wingers are the supposed terrorists. We were socialists after all, and it may be galling for so many who haven’t the faintest socialist instincts to nonetheless be tarred with that stigma. There is less and less left of liberal democracy, even compared to those tumultuous times. And the chances of its restoration are iffy. More gravely than in the sixties, the prevailing order is deeply undermined. Every attempt to defend or salvage it is perceived by those running things as subversive. The irony is palpable.

Charges of political terrorism today are ex cathedra and come, most of the time, without any real legal meaning or indictment. Instead, they function as a kind of excommunication for all those, liberal or left wing, who run afoul of the new regime. While instances of actual political terrorism, at least among those circles, is extremely rare, the accusation is effective, as it was for our little uprising long ago. It is demoralizing, in part because it’s not so easy to counteract, again as it was hard for us.

Perhaps the terrorism stigmas derive their ubiquity and undeniable traction from the sense we all share of how precarious the social order has become, that it teeters on the edge of mass mayhem. If there are legions of terrorists out there, that could explain things. Or more practically speaking, we live in a super-heated atmosphere in which depicting the enemy as satanic delivers real political returns. Terrorism is unquestionably the devil’s game. It inspires intense anxiety and a yearning for protection.

Liberal elites, who also get stigmatized in this way, find themselves in an uncomfortable position. Once they made use of the terrorism canard for their own purposes and, in extremis, were not averse to doing what they accused others of doing. Now, they call upon everybody to defend the liberal democracy. Their problem is that the ancien régime, the neoliberal one, exhausted its political capital by undermining and ignoring the well-being of millions of working people who once made up its social foundation. Cries to restore liberal democracy may ring hollow in those precincts.