“Movement Parties” and Democratic Socialists of America

The rapid growth of DSA in recent decades is part of a global phenomenon of voters and activists from the Left and Right who distrust the political establishment and traditional parties, and have formed what scholar Fabian Holt calls “movement parties.”

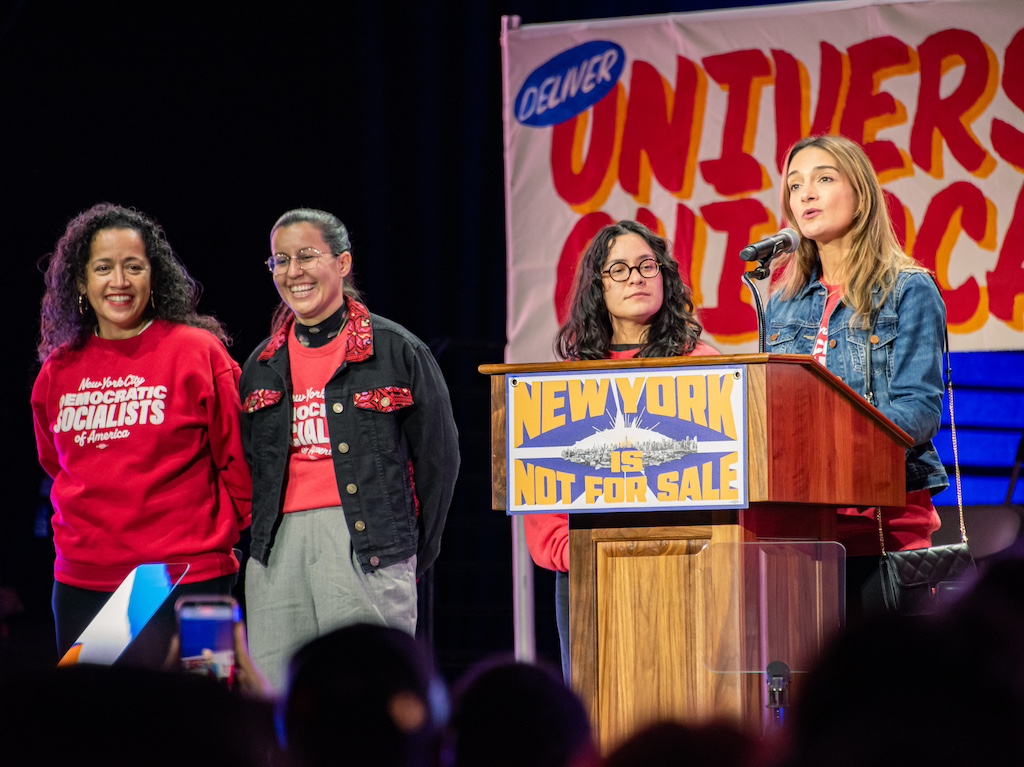

Fabian Holt shows DSA’s growth and challenges as part of a global trend of “movement parties” rather than a unique US phenomenon. (Neil Constantine / NurPhoto)

At the time of this writing, Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) is about to break 100,000 members, with nearly 14,000 of them in New York City alone. The election of Zohran Mamdani, a longtime DSA activist and New York assemblymember, as the city’s mayor brought unprecedented attention to the socialist group. Thousands of socialist activists have played a real and often unseen role in getting DSA to not only elect candidates but win public policy in places like New York.

In Organize or Burn: How New York Socialists Fight for Climate Survival, Fabian Holt breaks from other recent literature on DSA and its aligned movements by focusing on grassroots cadre instead of famous politicians. By doing so, Holt shows DSA’s growth and challenges as part of a global trend of “movement parties” rather than a unique US phenomenon — one that has more staying power, but also weaknesses, that both DSA’s supporters and detractors may miss.

For this research, Holt embedded himself in the New York City chapter of DSA (NYC-DSA), specifically the 2022 state senate campaign of democratic socialist David Alexis in Brooklyn. Participating in the political activity of rank-and-file DSA members around an endorsed candidate and analyzing how that shaped a chapter-level ecosocialist priority for green technology is a departure from recent literature looking at DSA and other new left formations.

Books such as David Freedlander’s The AOC Generation or Bigger Than Bernie by this publication’s editors Micah Uetricht and Meagan Day examine the growth of socialist- and social democratic–aligned movements around the rise of popular democratic socialist politicians. Organize or Burn uses a local city’s experience as a lens to understand statewide, national, and international political-sociological trends in movement activism.

This global framework is helpful in understanding why a group like DSA, even after its dramatic growth from 8,000 in 2016 to 25,000 members in 2017, still did not make environmental activism a priority at that latter year’s national convention, but six years later passed major ecosocialist legislation in New York State.

I was one of the many DSA members Holt interviewed for the book, but I had little clue whether the book would be useful or even accurate. Now that I’ve read it, I think Organize or Burn is the best book on the new Democratic Socialists of America yet.

DSA: A Movement Party, Not a Ballot Line

The specific framework Holt uses to analyze DSA is the “movement party”: a single organization serving as a nexus for activists of different social movements to shape electoral processes and outcomes. DSA organizers like me are wont to explain that DSA is not actually a party but a political nonprofit, a 501(c)(4). Critically, a movement party doesn’t have to be a legal party, as DSA is not. Also, movement parties are not inherently left-wing. The book cites the Tea Party, an insurgent Republican movement of the early 2010s that paved the way for President Donald Trump’s first victory, as another example.

Holt argues that DSA’s past decade of rapid change and growth (and occasional decline) is part of a larger global phenomenon in geopolitics, one he and others directly tie to voters and activists among the Left and Right who both distrust the political establishment and traditional parties and are more educated than the average citizen.

While movement parties arguably have been around since the 1980s, the book points to the research of Italian sociologist and political scientist Donatella della Porta, which contends that by the 2010s, movement parties had become a specific response to the enactment of unpopular austerity policies after decades of neoliberalism had already declined living standards across the world. The fact that older parties of the Left and Right instituted austerity measures eroded their legitimacy, which provided an opening for new movements.

Holt writes:

The core argument in much of della Porta’s work throughout the 2010s is that movement parties are relevant to restoring popular political participation and improving the capacity of parties to mediate interests in society. In a sense, the new movement parties are filling a gap left by old parties, which have become estranged from large parts of the constituency.

Holt adds to this the research of political scientist Herbert Kitschelt, which asserts that movement parties are made up of “new classes of educated voters [that] mistrust parties and are ready to defect and switch to competitors if their concerns are not serviced.”

Education levels are important to note because despite crafting a popular image of former Democratic-aligned working-class voters switching to the GOP, the Tea Party was largely made up of already conservative middle- and upper-middle-class activists who felt the Republican establishment wasn’t right-wing enough. What Kitschelt identifies about movement parties, which can be found in both DSA and the Tea Party for very different ends, is how they seek to elect their own adherents to office, are groups with low barriers to entry, and possess a strong willingness to use extra-parliamentary activism and disruptive actions to advance their agendas.

For the Tea Party, this type of direct action ranged from taking over congressional town halls around public discussion of Obamacare to the “Restore Honor” march led by then–Fox News host Glenn Beck, which, without any major organizational backing, drew nearly three times the attendance of the heavily labor-endorsed “One Nation Rally” around the same time in 2010.

While the Tea Party was a new political creature when it emerged during the Obama era, DSA has existed since 1982 as the product of a merger of two preexisting socialist groups. Holt’s work does an excellent job of moving beyond the simplistic understanding of the “old DSA” (pre-2016) as “marginal” and of providing a more nuanced explanation of the growth of the “new DSA” (post-2016) that goes beyond a single person such as Bernie Sanders or reasons like Trump’s election.

Early DSA was led by prominent left intellectuals such as anti-poverty activists and social critics like Michael Harrington and Barbara Ehrenreich, who both cochaired the group at different times. DSA was, and in some ways arguably still is, better known for its celebrity members than any single action or program. But as the book notes, the most prominent members have shifted from well-known writers to national political figures like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Also, DSA’s activism and constant media attention to NYC-DSA’s electoral and other movements has shown that the group’s membership is critical in keeping higher-profile individuals in office and enacting social change aligned with the socialist mission.

A peculiar difference between DSA and other left-wing movement parties abroad is that the US group has existed in some form for nearly half a century. The book chronicles how DSA changed its mission and its member demographics without forming a new socialist party. Until 2017, DSA was a member organization in the Socialist International (SI), a global association of traditional socialist and social democratic parties. A major reason cited by members for leaving the SI was that those sister parties had been responsible for implementing austerity measures. In Europe, diverse and younger activists formed new parties like Syriza in Greece that broke from such social democratic parties. By contrast, DSA was able to move first symbolically, then materially, toward looking and acting more like a movement party than a traditional party.

But actions like leaving the SI were not what drove people to DSA. Holt does an excellent job of explaining DSA’s growth not only in relation to historic events that are more commonly known, like Sanders’s first presidential run, but also the politicizing movements a few years earlier and organizational decisions, all of which would play a role in largely young activists picking DSA as their political home.

Through interviews with numerous DSA cadre, specifically millennials who made up the bulk of the first surges in membership, disappointment with Barack Obama’s presidency, and his inadequate recovery efforts during the Great Recession in particular, moved many to later join DSA. The Occupy Wall Street movement and its rhetoric of the 99 percent gave a class-focused language that people could latch onto. Holt credits Jacobin reading groups as a refuge for many who would later join DSA, including future New York state senator Julia Salazar.

Even with the increased profile of democratic socialism thanks to Sanders’s campaign, DSA grew slowly, reaching about 8,000 dues-paying members by 2016, up from 6,000 a few years earlier. But membership ballooned after Trump’s first presidential win. While many activists were pulled toward democratic socialism because of Sanders, the push toward joining DSA and becoming active in the organization was rooted in their lack of faith in existing liberal institutions to stand up to Trump. If there was one thing that grew DSA, it was what has facilitated movement parties everywhere: motivated people’s desire to tackle inequality made worse by neoliberalism.

Ecosocialism: From Afterthought to Priority Campaign

Organize or Burn uses NYC-DSA, specifically Alexis’s race in 2022 and its connection to the Ecosocialist Working Group’s (ESWG) Public Power campaign, as a lens to explore the global dynamics described above — not only through a city-level framework but also to combine it with the issue of climate justice as a driving force in political decisions.

NYC-DSA is the largest DSA chapter by far, representing over 10 percent of the national membership. It also reflects DSA’s predominantly young demographics. Holt contends that, while the chapter is majority white, it is more ethnically and racially diverse than some of its critics would let on. For instance, Holt observed by the end of the Alexis campaign, one-third of the volunteers were people of color.

Holt’s ethnographic research included embedding himself in the Alexis campaign, observing how DSA members petition for their candidate’s spot on the ballot and engage in electioneering in general. Holt notes that while heavily focused on electing Democratic candidates, NYC-DSA differs from Democratic clubs, which can have a political or ethnic/demographic focus, because they not only solely back socialists but do this electoral work as part of a broader social movement. (Holt did note, however, that these clubs and the Democratic “machine” are in decline, which has given space for NYC-DSA to succeed by driving high volunteer numbers in ways their rivals in Democratic primaries often cannot.)

DSA sees socialist elected officials as partners in advancing socialist-aligned goals in environmental, labor, and other movements. Within DSA, working groups are facilitators between particular movements and the socialist organization itself. The ESWG is one such example that connects climate justice demands and organizations to DSA’s electoral strategy.

Climate justice is a relatively recent priority for DSA. As a long-time member, I know that although comrades have always cared about the environment, it rarely went beyond a workshop at a pre-2016 conference. The same convention that voted to leave the SI did not make ecosocialism a priority but the subsequent convention in 2019 did. Through NYC-DSA, we see the downstream effects of this internal shift and its external consequences.

Socialists Win “Public Power”

Holt uses the passage of the Build Public Renewables Act (BPRA) and the ESWG’s role in the legislative success of the act as a guide to show how movement parties like DSA work in practice. In 2019, while national DSA was taking ecosocialism more seriously, the NYC chapter also voted to make Public Power a priority campaign at its local convention. This effort focused on the New York Power Authority (NYPA), a publicly owned entity that they felt was underutilized. The Public Power campaign revolved around passing the BPRA, which would give the NYPA more authority to build renewable energy in the interests of working people.

One tactic of this campaign was backing socialist state legislative candidates who supported the BPRA. DSA won all five of its state assembly and state campaigns in 2020, but it became clear that even these victories would not be enough to pass the BPRA. To actually get the bill passed, the ESWG realized it needed to pressure electeds, especially those tied to the bill, whether they were socialist or not.

One simple way for the group to do this was to push champions like then-congressman Jamaal Bowman to use his large platform to promote Green New Deal–type policy. But a more direct approach, in line with what separates movement parties from Democratic clubs, was to challenge incumbents in primaries while simultaneously carrying out disruptive direct actions.

DSA organized public events, including some that could result in arrest, to draw attention to its Public Power campaign and highlight anti-green-energy corporate contributions that nonsocialist incumbents were accepting. While Alexis did not defeat his opponent, the ostensible lead sponsor of BPRA, the winner only got a plurality of the votes. Feeling the pressure from his primary challenge, he then worked with Governor Kathy Hochul to pass the bill by 2023, likely to avoid another primary.

BPRA’s passage resulted in socialists leading a nexus of different parts of civic society: elected office, environmental activism, and street pressure. Such a convergence of different groups can only happen in a movement party like DSA. Holt writes:

NYC-DSA evolved into a movement-based organization with party elements and capacity for long-term organizing. It created the movement party environment in which socialists and climate professionals could develop BPRA. BPRA could not have been developed in the Democratic Party. The six-year process that culminated in the passing of the BPRA shows the organization’s long-term capacity and movement party dynamics.

In Organize or Burn, Holt demonstrates what makes DSA special in US civic society today. DSA is one of the few places — and one that largely younger people have used — to do politics in community and grow as leaders. DSA’s democratic structure and low barriers to entry give rank-and-file members a chance to rise up in leadership on their own merit.

Holt does not idealize DSA chapter activism or leadership. He highlights, as anyone who is heavily involved knows, that there is real turnover and burnout in the organization, especially for those responsible for internal governance. And the demographics of DSA aren’t always as diverse as the group itself wants, even if its demographic skew is sometimes exaggerated by bad-faith critics. But Holt argues that the democratic nature of DSA is preferable to stable but unchallenged leadership. DSA still offers a lot of hope and potential to make a real impact on society, and the book helps us understand why people stay in DSA as much as why they join.