Mohammed Harbi Was Algeria’s Revolutionary Historian

Mohammed Harbi went from participating in Algeria’s independence struggle to writing some of the most important books about its history. Harbi, who died last month at the age of 92, was a creative Marxist thinker and a champion of democracy in Algeria.

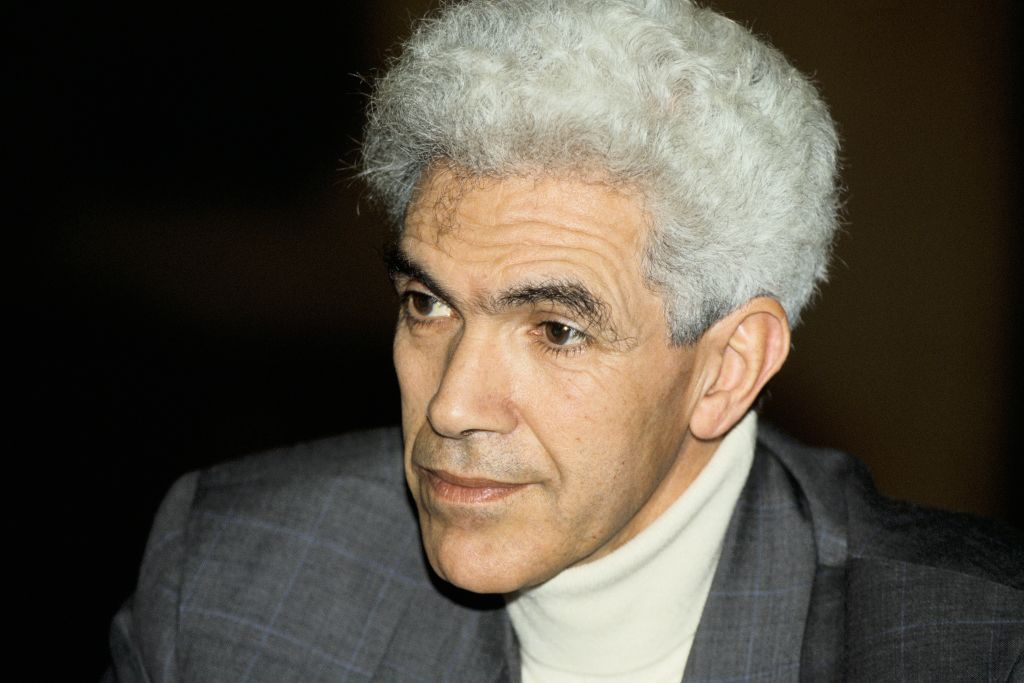

Mohammed Harbi offered us an invaluable set of tools with which to understand the past. (Nacerdine Zebar / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Reflecting on his pathbreaking history of Algeria’s National Liberation Front (FLN), first published in 1980, the Marxist historian and Algerian militant Mohammed Harbi wrote that his main goal had been to “avoid any confusion between the historical specificity of Algerian society and that of global capitalism.”

At the same time, he explained, the book, which was provocatively titled The FLN: Mirage and Reality, aimed to deconstruct the myths associated with the revolutionary force that won independence for Algeria after 132 years of French colonialism. These two goals — adopting a Marxist methodology that took seriously the specific social formation of Algerian society and rejecting a hegemonic reading of Algerian nationalism — were inseparable for Harbi, who passed away in Paris last month on the first day of January.

In his long career, Harbi always insisted that one could not understand Algerian history and its process of decolonization by simply applying forms of class analysis that were based on European experiences. Yet he also rejected essentialist understandings of ideology or culture. Through this double refusal, he offered us an invaluable set of tools with which to understand the past. Harbi’s writings also illustrated a model of internationalism that refused to accept the authoritarian nature of specific nationalist projects, even if these projects were based on anti-imperialist principles.

“A Marxist in a Nationalist Struggle”

In his life and work, Harbi rejected the political orthodoxies and expectations of those around him, whether they were espoused by members of his family or the political party to which he belonged. In his autobiography, Une vie débout, he famously wrote: “As a Marxist in a nationalist movement, I often found myself swimming against the current, amid traps and suspicions of all kinds.”

Coming from an aristocratic family that had (on his mother’s side) experienced a sharp decline in social status due to the French colonization of Algeria, Harbi observed from an early age how religion became a central element of nationalist consciousness. Yet he was critical of both the French and Quranic schools that he attended, defining himself as a cultural hybrid (métis culturel). He defined the former as a place of ideological subjection (assujettissement) and recalled his disgust at having to sing the Vichy anthem “Maréchal nous voilà” during World War II.

Born in El Harrouch in northeast Algeria in 1933, Harbi moved to the coastal town of Skikda in 1945. Both areas were bastions of Algerian nationalism, which he first came across through the scouting movement. The massacres in Guelma and Sétif on May 8, 1945, were a watershed for Harbi, as was the case for many of his peers. These episodes of colonial violence came after protests against the deportation of Messali Hadj, a leader of the Algerian People’s Party (PPA), the Algerian nationalist movement that first called for independence from France.

The brandishing of PPA flags and violence against Europeans led to massive reprisals by French colonial forces, which killed up to 45,000 people, including members of Harbi’s own family. While most historians considered that the Algerian revolution (led by the FLN) began on November 1, 1954, Harbi argued that Guelma and Sétif constituted the “real beginning of Algeria’s war of independence.” After these events, the PPA changed its name to become the Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Liberties (MTLD). In 1946, Harbi became the head of the party’s local section at his high school.

While the events of 1945 cemented his allegiance to the nationalist cause, his time in Skikda, where the French Marxist Pierre Souyri had been his teacher, nurtured a commitment to anti-Stalinist socialism. Harbi mentions the influence of the Socialism or Barbarism (SouB) circles multiple times in his writing. SouB, which developed out of Leon Trotsky’s Fourth International, included figures such as the philosophers Cornelius Castoriadis and Jean-François Lyotard. Lyotard was a friend of Souyri and a strong advocate for Algerian independence.

Harbi’s drive to think about national and social questions as two essential components of emancipation continued to mark his life as a militant, even after he left for Paris in 1952. These were difficult years for Algerian nationalism. Messali’s movement experienced internal divisions, an episode that Harbi characterized as the most “painful ordeal” that he went through as a militant.

The PPA and its successor, the MTLD, were largely organized around the personal charisma and populism of Messali, who rejected the reformist character of revivalist nationalist organizations such as the Democratic Union of the Algerian Manifesto (UDMA) or the movement of Islamic reformers. However, his followers ultimately split into three factions: those who remained loyal to Messali (“Messalists”); those who called for direct action, dismissed electoral politics, and lamented the “cult of personality” around his leadership (“activists”); and a third current that worried about Messali’s leadership style but nevertheless remained committed to a political solution that would prepare the terrain for future armed struggle (known as “centralists”).

Before embracing the more militant tendency that would ultimately evolve into the FLN, Harbi identified with the last group. Yet when he later wrote about these divisions, he insisted that the divergences were not merely a function of strategical or ideological differences but were ultimately rooted in the petty bourgeois character of the party’s leadership.

An “Authoritarian Mobilization:” The Victory of the FLN

Harbi’s long engagement with the PPA/MLTD made his eventual adhesion to the FLN a fraught decision. The new party, founded in 1954, presented itself as possessing a monopoly on the nationalist field and representing a fundamental rupture with past organizations. This was in spite of the fact that, as Harbi remarked, all of their leaders been politicized in Messalist circles.

The FLN assassinated many supporters of Messali, who now organized under the banner of the Algerian National Movement (MNA), during the war of independence. The Algerian Revolution not only sought to rid the country of French rule but also involved a “war within a war” between the two primary nationalist groups. As the FLN came to monopolize the struggle, Harbi reluctantly joined it, despite the lack of pluralism that he characterized as a “authoritarian mobilization.”

Harbi joined the French Federation of the FLN in August 1956, playing a key role in the Information and Press Commission. He remained disturbed by the FLN’s stated goal of restoring an Algerian state “in the framework of Islamic principles.” For Harbi, this claim reflected an instrumentalization of religion and a misguided sense of continuity between the Ottoman period and the present. He also insisted that while the FLN’s brand of nationalism set out to create a community, it overlooked the need to create a society.

He put forward a similar critique of his former Messalist comrades, who had also prioritized the national movement at the expense of a workers’ movement and had viewed Algerians as a “people-class.” Harbi robustly challenged the perspective of those like Frantz Fanon who insisted on the revolutionary nature of a flattened subject called “peasant.” This notion, he wrote, “did not correspond either politically or socially to the reality of this class.”

Harbi rooted these failures in an analysis of colonialism. French rule, he argued, had given rise to a fractured society, divided along regional and ideological lines. For Harbi, class categories that were often rooted in the genesis of capitalism in Europe failed to capture the de-structuring of Algerian society.

The main characteristic of the FLN’s leaders, according to Harbi, was not their status as members of the petty bourgeoisie, but rather the fact they had experienced downward social mobility due to colonization. These individuals had “severed their ties with their original social background in order to establish new connections with both the urban and rural masses.” The radical claims of the FLN leadership (and their reluctance to think in class terms) reflected the fact that their social cohesion derived from the injustice of the colonial system, and their conviction that armed struggle was the only possible recourse for emancipation.

Harbi’s time working with the FLN took him to Germany, Switzerland, Tunisia, and Egypt, before he broke with the party in 1960. In his letter of resignation, he accused his former comrades of intentionally distorting

a discussion on the fundamental problems posed by the revolutionary uprising of our people (the need for an avant-garde organization linked to the fighters and the people and leading the country from within, the role of Algeria in the Arab movement for unity and independence, the urgency of a political and military strategy encompassing the Arab Maghreb, the fight against opportunistic tendencies, the conditions for a long-term war).

Harbi nevertheless continued to support the nationalist cause and contributed to the drafting of the Tripoli Program, a document that outlined the character of the revolution after independence. Yet he was again disappointed by his comrades: in Harbi’s view, they hoped to avoid the capitalist path while denying the political or economic role of the private bourgeoisie due to “the illusion of a harmonious coexistence between this class and the bureaucracy, and the naive belief in their capacity to amicably share the proceeds of labor exploitation.”

Self-Management Against the State

Harbi played a key role in the design of agrarian reform and a policy of agricultural self-management after independence in 1962. European settlers fled their lands, and rural Algerians spontaneously occupied these abandoned plots. International advisors such as Michalis Raptis (who Harbi had met in 1956), Lotfallah Soliman, and Algerian-born European supporters of the FLN like Yves Mathieu penned the 1963 March Decrees that formalized the administration of these nationalized properties.

In April of that year, Harbi joined the National Bureau of the Socialist Sector (BNASS). In September, he also took on the role of editor at the FLN newspaper, Révolution Africaine, aiming to “Algerianize” a publication that had previously been under the control of figures like Jacques Vergès and Gérard Chaliand.

The welcoming mood toward international leftists was short-lived. By 1964, tensions between the FLN’s leftist wing and President Ahmed Ben Bella were evident. In 1965, a military coup by Houari Boumédiène ousted Ben Bella and spurred the exodus of his cosmopolitan fellow travelers. The government tightened control over Revolution Africaine and Harbi found himself first in prison, then under house arrest, before managing to escape to France in 1973.

Harbi was not the only nationalist who became a victim of the same state he had helped usher into being. Reflecting on the fate of his comrades such as Mohammed Boudiaf, Belkacem Krim, and Ben Bella, who all faced assassination, prison, or exile, he concluded that the Algerian war of liberation had constituted a “bureaucratic revolution” of a kind that was common in the Third World.

The FLN was not, in his analysis, a political party of a front of autonomous organizations. Instead, he defined it as a grouping of social forces with internal contradictions such as regionalism, militarism, and a secretive nature that had been structured by the experience of colonialism and armed struggle. The state apparatus, especially the army, had catalyzed the formation of a new bourgeoisie after independence, while simultaneously reshaping the working class and co-opting the intelligentsia.

As a militant and then as a scholar, Harbi paid a heavy price for refusing co-optation by the post-revolutionary system. Some of his works were banned in Algeria and others remained difficult to find in university libraries.

From Decolonization to the Present: “Apprentice-Sorcerers”

Since independence, the Algerian state has faced contestation from those calling for cultural and political pluralism. In 1980, during the so-called Berber Spring, protesters demanded the integration of Tamazight languages in Algerian schools, a reform that government leaders presented as a threat to the state’s Arabo-Islamic identity. Harbi’s words, published in the spring of 1980, remain prescient:

Algeria is in the hands of apprentice-sorcerers who, without principles, have played social classes against one another and are capable of setting Algeria’s regions against each other in order to hold on to power. Meanwhile, men are in prison, accused of undermining national unity.

When a civil war broke out in Algeria during the early 1990s, Harbi was again a voice for pluralism and democracy. He refused to support the state’s cancellation of the 1992 elections, which the Islamic Salvation Front was expected to win, despite his deep skepticism regarding the place of Islam in public life (including in France).

In 2019, a popular uprising known as the Hirak ousted Algerian president Abdelaziz Bouteflika, a veteran of the independence war. In many ways, these protests seemed to be a continuation of the demands for democracy and independence that Harbi viewed as an unfilled promise of the 1962 revolution.

Writing in 1975, he complained that for all the talk of “decolonizing history” in Algeria, “the historical and sociological work relating to the national movement is, in many respects, an anthology of falsification and concealment.” By this he meant that official historiography continued to depict Messali as a traitor while celebrating reformist figures such as Abdelhamid Ben Badis.

Yet during the Hirak, many of these marginalized figures appeared on posters carried by protesters who appeared to be writing a new history of their revolution. Harbi acknowledged that even if the Hirak did not follow his vision for revolution, the movement displayed a creativity and dynamism that, regardless of the outcome, had the power to regenerate Algerian society.

One can imagine that the lack of a distinct leadership or a clear set of class-based objectives in 2019 troubled Harbi. The tension between protests that work across class boundaries based on broad demands, and the potential for those protests to be channeled into political mobilization and labor organizing, remains a challenge for the Left. Against comrades who had a more spontaneous understanding of revolutionary possibilities, Harbi insisted that class consciousness and nationalist commitments were not simply the reflection of preexisting revolutionary capacities but were forged through shared political struggles.

From the War of Liberation to the Hirak, Harbi refused to subsume the need for political pluralism or social emancipation to the project of anti-imperial nationalism. As Ayça Çubukçu has recently argued, today we face a tendency to cast any attempt to move beyond binary and statist logics as an apology for empire and genocide. Çubukçu highlights the need to think carefully about motivations and political calculations before offering a critique of anti-imperial struggles. At the same time, she warns us against turning a blind eye to the internally directed violence or class composition of anti-colonial movements.

For those who are grappling with these questions, and who believe that past anti-colonial struggles offer both lessons and warnings for our political present, the writings of Mohammed Harbi will long remain essential.