Four Lessons From the UAW’s Turn Toward Class Struggle

Chris Brooks, former chief of staff to United Auto Workers president Shawn Fain, was key to an attempt to transform a once mighty union hobbled by corruption and lethargy. Here’s what he learned from that process.

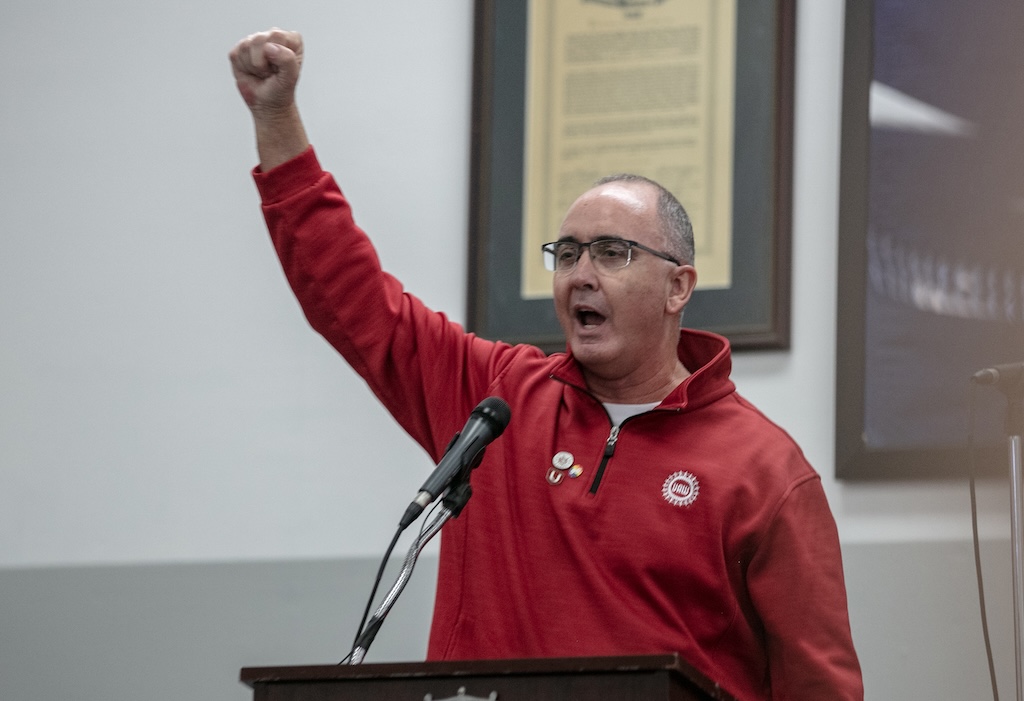

UAW president Shawn Fain addresses autoworkers at a rally at the UAW Local 551 hall in Chicago. Illinois, on October 7, 2023. (Jim Vondruska / Getty Images)

Shawn Fain won the runoff to be president of the United Auto Workers (UAW) in March 2023, and the union he was elected to lead was in free fall.

The standard of living for unionized autoworkers had once been the aspiration of blue-collar workers everywhere. But after decades of concessions, the lives of new hires at Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis now resembled that of their nonunion peers at Toyota, Honda, and Mercedes.

A wide-ranging federal corruption investigation had sent a number of high-ranking UAW officials to prison, including two previous presidents. The UAW’s Detroit headquarters, affectionately named “Solidarity House,” served almost as a physical allegory for the union. At the time of Fain’s victory, it sat vacant, having been gutted to the studs and completely rebuilt following a highly suspicious fire several years before.

And Fain was inheriting a deeply divided union, having won the runoff election for president by only a few hundred votes. The day Fain was sworn in, the outgoing president Ray Curry handed him a single sheet of paper with a few barely legible, hand-scrawled notes. That was the entirety of the transition.

The very next day, Fain presided over the union’s Special Bargaining Convention, a monumental conference held every four years to lay out the union’s big picture bargaining goals — particularly for negotiations at the Big Three, which were set to kick off in a mere six months. The conference was mostly attended by union delegates from the Administration Caucus, the internal leadership organization that had essentially run the union as a one-party state for the past seventy years, and that Fain’s Members United Slate had just given a shellacking. The reception could not have been chillier.

Fain’s upset victory in the UAW, much like Zohran Mamdani’s election in New York City, speaks to a simple truth: militant reformers don’t typically come into power when things are going well. We win because institutions, whether an international industrial union or City Hall, have been badly damaged by the corruption and failures of past generations of leaders.

Fain and Mamdani must deliver on their respective visions by winning historic gains that challenge elite power while simultaneously rebuilding the collapsing institutions they inherited — all while facing off against internal resistance, corporate backlash, and rising right-wing authoritarianism.

At the time of his election, the tasks before Fain were enormous: build a team, unite the union, rebuild public confidence, and, to quote Fain’s speech at the Special Bargaining Convention, “ready ourselves for the war against our one and only true enemy: multibillion-dollar corporations and employers that refuse to give our members their fair share.”

I was Shawn Fain’s transition team manager and his chief strategist once elected. Here are some of the lessons we learned in trying to shake things up and deliver big wins in the first year at the UAW.

1

Planning, discipline, and democracy go hand-in-hand.

We assumed that we had six to twelve months to drive significant change and demonstrate results before staff aggressively asserted old ways of doing things and the membership grew cynical or disillusioned. We also knew internal and external opposition would work to relentlessly distract, undermine, and destabilize us unless we had a clear plan that we executed with discipline.

Our top priority was to win the strongest Big Three contract in decades through the union’s first ever national contract campaign, uniting members around ambitious demands to secure the kind of victory that could reignite faith in the union and demonstrate that mass mobilization and sustained engagement are the real source of our union’s power.

The timeline was brutal. Fain was elected at the end of March, bargaining began in July, and the contracts expired in mid-September.

Fain was adamant that the contract expiration was a strike deadline, so we set it as our North Star and worked backward, creating one-, two-, three- and six-month plans focused on the changes needed in the departments that form the core infrastructure required to run a high-participation, multiemployer contract campaign and strike: the organizing department to mobilize members at scale; the communications department to bring the bargaining table to the shop floor through regular updates and shape the narrative and maintain momentum; the research department to identify and target employer pressure points; the political department to convert relationships with elected officials and agencies into external pressure; and the legal department to provide creative strategies that enabled — rather than constrained — bargaining and strike escalation.

Because we were breaking sharply with decades of entrenched UAW practice, it was essential that the plan had a disciplined rollout and was understood and owned by every senior leader Fain appointed. One of the clearest breaks was the union’s long tradition of “blackout bargaining,” in which the union’s top brass cut deals behind closed doors.

“You are supposed to go into the back room,” said Terry Dittes, UAW vice president overseeing General Motors, according to a transcript of an August 2019 International Executive Board meeting. “If we have all kinds of messages out there, we build up expectations.”

The dedication to secrecy worked. The very next month, forty-nine thousand members at GM went out on strike with little idea of what their union was even fighting for.

We were committed to radically changing the UAW’s culture of secrecy and control. From the outset, we created urgency and clear expectations by ensuring top staff and department heads could articulate Fain’s vision for a fighting, member-driven UAW, understood their role in executing it, and embraced the need to work differently to win different results. The plan, developed during the runoff and executed immediately upon taking office, was a living strategy, refined by creating opportunities for an ever-expanding circle of leaders and top staff to debate and supplement it as bargaining approached.

For example, in early summer 2023, the president’s office organized a week-long retreat with senior staff and the vice presidents overseeing Ford, GM, and Stellantis to analyze the companies and align bargaining priorities, contract campaign strategy, and strike preparations. We were shocked when veteran leaders who had been intimately involved in past negotiations going back decades told us this was the first union-wide pre-bargaining planning meeting they had ever attended — a reflection of a past culture that relied on secrecy and backroom deals rather than democracy and member power.

The planning didn’t stop at the top. Bargaining teams from around the country were brought to Detroit to roll out the “Members’ Demands,” the UAW’s top bargaining priorities in negotiations, which were then shared publicly through Facebook Live and regular updates. In defiance of the union’s paranoid culture of blackout bargaining, Fain provided ongoing, transparent updates on negotiations and company proposals.

From the first day in office to the day we went on strike, we hammered the same message: our demands are ambitious, the companies could afford them, and what we ultimately end up winning will depend on collective action. Our success hinged on everyone — from a researcher costing proposals in Detroit to a local president organizing their first practice picket in Arlington, Texas — understanding and contributing to the plan and then being ready to play their part.

2

Personnel is policy.

Staffing is one of the most critical and immediate questions of any new administration trying to fundamentally change how things are done. After all, a plan is only as good as the people you have to execute it. And the first question that newly elected reformers will face is whether they should clean house.

Union leaders have this right. In fact, the US Supreme Court in Finnegan v. Leu explicitly ruled that the right of union leaders to remove staff and appoint others (absent a collective bargaining agreement or individual employment contract that states otherwise) who they believe can best effectuate the will of the membership is a fundamental principle of union democracy.

It’s common sense: newly elected leaders can’t be saddled with the top lieutenants of the incumbents they just defeated if they hope to take the union in a new direction and be successful. After all, if a progressive champion of the working class were to be elected US president in 2028, they wouldn’t keep Donald Trump’s appointees.

But after seeing how divided the union was at the Special Bargaining Convention and how short our runway was to Big Three bargaining, Fain decided against cleaning house. That didn’t mean we were blind to the problems with old staffers.

Like many business unions, the UAW’s decline was facilitated in part by a sprawling patronage system in which some leaders appointed staff based on who they were related to or in exchange for favors, rewarding those who turned out votes in internal elections or successfully pressured locals to ratify awful contracts.

To be clear, the UAW has long employed many smart, creative, and deeply committed staff. But some prior leadership treated the union as a jobs program for relatives and loyalists, using staff to control the membership so they could cut sweetheart deals with employers and spend less time in bargaining and more time on their golf game.

Under the new Fain administration, this model was upended. Winning for our members, not controlling them, is what mattered most. Staff were now expected to support local leaders, organize members to confront the boss, and help build power on the shop floor. This was a 180-degree turn from what had been asked of them before.

This meant there was a significant skills gap between many of the staff and our plans. Many auto organizers had never been trained to conduct organizing conversations, let alone to train members to do the same. Most servicing reps had never trained bargaining committees on how to write effective bargaining updates, much less organized large numbers of members to attend and participate in bargaining or coordinated escalating workplace actions to generate leverage.

Staff responses to the new direction could easily be mapped along the Labor Notes bullseye. Some were energized and eager to learn and lead. Others hoped to keep their heads down and coast. A smaller group, recognizing that they would be held accountable to new expectations, tried to sabotage the plan and the newly elected leadership.

Given the gap, bringing in outside staff — including me — was essential to help design, guide, and enforce the culture shift and new practices in the union. But we also found that there was a real danger in outside staff becoming too fixated on the internal dysfunction, the lack of training and experience, and the obstruction, because it obscured a more important reality: a large share of the staff were winnable, capable of learning, and ready to grow.

Our approach was therefore to train while doing — building real-time learning into campaigns — and to move as quickly as possible toward a model where staff could train and lead each other. Equally important was publicly sharing credit for wins, whether a highly attended rally, an organizing breakthrough, a contract victory, or a viral video. Collective ownership of our successes built goodwill, confidence, and momentum.

None of this eliminated serious staff problems. Disciplines and terminations were sometimes necessary when staff were insubordinate or actively sabotaging the program. But clear, repeated communication of the vision — paired with defined roles, support, and training — created excitement, encouraged risk-taking, and made growth possible.

In fact, some of Fain’s most trusted and effective senior staff were initially outspoken opponents during his election. It’s a great example of the old organizer maxim: we win people over, we don’t write them off.

For socialists, this lesson matters. Because we so rarely govern, breakthrough moments often arrive before we are fully prepared for leadership. We discovered that winning over experienced staff who understand and can navigate the bureaucracy is just as critical as bringing in outside talent with new skills. Durable transformation requires both.

However, the challenges of fundamentally changing the culture in departments can be significant. We learned that sometimes, if you want to get somewhere new, it’s best not to rely on the old roads but to make new ones.

Following the success of our Stand Up Strike at the Big Three, we created the Department of Bargaining Strategies, a whole new department that wasn’t beholden to the old ways or the old guard, with the sole mission of being an engine for culture change in the union by providing training, resources, and support to locals in various sectors on how to run aggressive, high-participation campaigns.

This new department was designed not just to win strong contracts, but to demonstrate — over and over again — that an organized, militant membership is more powerful than backroom relationships, and that strong contracts are won through collective power, not staff diplomacy. It wasn’t enough to end “blackout bargaining” at the Big Three; we needed to end it everywhere in our union.

Blending a mix of new hires who had experience running aggressive contract campaigns in other unions and the most enthusiastic “social arsonists” we could find from within the UAW (that is, organizers who can really light others on fire and get large numbers of people in motion quickly), the Department of Bargaining Strategies quickly became a massive success, supporting locals representing workers at Daimler, Rolls Royce, Allison Transmission, Cornell University, GE Aerospace, and other employers to make massive gains in negotiations.

3

Ignore the bulls—t. Trust the membership.

There are countless ways that frivolous, bad-faith outrage was weaponized by our opposition to try and derail progress.

For example, there was considerable angry chatter among staff and some members on social media directed toward Fain for “hiring outsiders” (meaning people who were not UAW members at the time they were hired), which was obviously coded backlash from those who benefited from or hoped to benefit from the union’s patronage system. These attacks weren’t a sincere concern over principles but resentment from the small clique who treated the union as their private club and were now losing control of the member-funded gravy train.

It cannot be stressed enough how important it is for leadership to ignore the manufactured drama and stay focused on what members truly care about: whether their lives are better today than they were yesterday.

The vast majority of people do not care about the palace intrigue at union headquarters or about that tweet from six years ago that the right-wing media is desperately trying to turn into a scandal. Workers care about making a living wage, being able to take their kids to the doctor or get an operation without going broke, retiring with dignity and security, and having time with their friends and family.

Changing those material conditions is incredibly hard. It requires wresting power and wealth away from employers and billionaires, a task that becomes impossible if leaders allow news cycles driven by our enemies to dictate their decisions, or if it keeps them from retaining highly competent, experienced staff.

When in doubt about whether the outrage in the media is real, the answer is simple: touch grass. Go be with the members. Host a town hall. Attend a local meeting. Meet with a retiree chapter. Just talk to members and listen. If members are not even aware of the social media chatter or are totally indifferent to that New York Post story, then that tells you everything you need to know.

It’s important to remember: our opposition is never going to stop trying to sow doubt and division, so we must be equally unrelenting in our determination to strengthen the bonds between the reformers at the top and the base at the bottom who put us there.

4

Our greatest resource is each other. Our greatest challenge is that there are too few of us.

In just three years, the UAW has made huge strides away from being a business union defined by corruption and concessions to a movement union committed to building working-class power. I’m proud of the member-driven campaigns we ran across the country that resulted in record contracts for our members — not just in the auto industry, but in higher education, heavy truck, aerospace, defense, and parts suppliers.”

But that progress is not secure. Reaction will always try to reassert itself. Employers, threatened leaders, and entrenched staff will try to reverse the changes made and restore the old order that they benefited so greatly from. And while progress is always vulnerable, that can’t be an excuse for not continuing to scale our fight for another world.

Our goal can’t just be to win incrementally better contracts or free buses, as vitally important as both of those are. It’s to fundamentally shift the balance of power in society away from billionaires and employers and toward the working class.

This is one of the other great lessons from the UAW experience: what we can achieve and the security of our progress is determined by the size of our cadre.

One of the realizations we had was that even if we had cleaned house in the UAW, there weren’t enough serious cadre willing to move to Detroit or work long hours on organizing drives in Alabama or in negotiations in Indiana to backfill the positions.

The Left faces a classic chicken-and-egg problem: we lack a deep bench of experienced leaders and operatives to govern and transform institutions, which means we have to capitalize on every breakthrough moment by recruiting who we can and using the opening to train a new generation of militants. We have to win gains and grow our ranks. It’s hard to overstate how important it is to address the Left’s leadership deficit in the labor movement.

The global working class has entered an era of compounding crises: accelerating climate catastrophe, extreme inequality, and rising right-wing authoritarianism. As liberal capitalist democracies continue to fail working people, anger will grow, creating openings both for socialist leadership and for the far right.

To meet that moment, we need more than a handful of class struggle unions or socialist mayors. We need a class struggle labor movement and a class struggle political party. That requires many more capable leaders than our movement has now.

The scale of what we can win and what we can hold will ultimately be determined by the size, skill, and cohesion of militant left-wing leadership.

People with experience making hard decisions under intense conditions, people who have built and led teams into battle, people who can develop dynamic training programs to grow our army of fighters. People who can change history, but not under conditions of our own choosing.