Reassessing the People’s Hospital in the Bronx

After a militant 1970 hospital takeover birthed a pioneering detox program in the South Bronx, New York City is now studying what it dismantled, and what redress requires amid an ongoing overdose crisis.

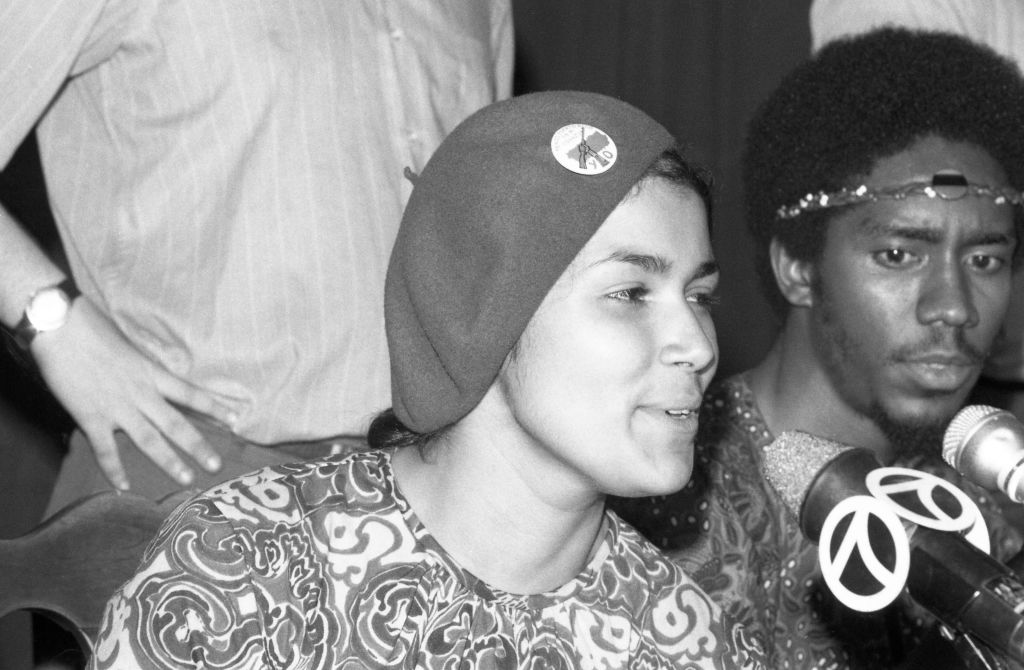

Gloria Cruz (left) and Jack (no last name given) talk with newsmen on July 14, 1970, about why the Young Lords took over the old nurses' residence at Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx. (Bettmann Archive / Getty Images)

At 3 a.m. on a summer morning in July 1970, a group of activists climbed into the back of a rented U-Haul truck believing they might not make it out alive.

The action was led by members of the Young Lords — a predominantly Puerto Rican revolutionary organization — and included members of the patient-worker “Think Lincoln” committee and the Health Revolutionary Unity Movement (HRUM), a formation of left-wing black and Puerto Rican hospital workers. Roughly 150 people were involved in the takeover of the hospital’s nurses’ residence building in the South Bronx on July 14, 1970.

By dawn, they were inside. A Puerto Rican flag hung from the building. A banner read: “Welcome to the People’s Hospital.”

Lincoln was the main public hospital serving one of the poorest congressional districts in the country. Residents called it a “butcher shop.” Paint peeled from emergency room walls. Roaches crawled into pill cups. Infant mortality in the surrounding neighborhood far outpaced city and national averages. Days after the occupation, a young woman named Carmen Rodríguez died at Lincoln following a legal abortion procedure — her death becoming, for many Bronx residents, further evidence that the hospital’s standard of care was not simply stretched but dangerously inadequate.

More than fifty years later, that confrontation is the subject of a city-funded, yearslong project inside the New York City Department of Health, a process that brought former Young Lords and public health officials together last week at Hostos Community College to revisit what was built, how it was dismantled, and what repair would now require.

The Takeover

The Lincoln Hospital takeover did not erupt from nowhere. In the months leading up to July 1970, the Young Lords and their allies had already been running what they called a “health offensive” in the South Bronx. They seized a city-owned X-ray truck and drove it through the neighborhood with the original technicians to test residents for tuberculosis, arguing that if the city would not provide preventive care, they would. They demanded lead poisoning screenings for children. HRUM members brought hospital workers into the fight, linking unsafe working conditions to patient neglect.

Writer Barbara Ehrenreich worked with the Young Lords around the Lincoln campaign, helping document hospital funding structures and the broader political economy of urban health care. As Juan González, a leader of the Young Lords in the 1970s, recalled in reflecting on her life, Ehrenreich helped situate Lincoln within what activists were beginning to describe as a “health-industrial complex” — a system in which poor communities were systematically underserved while private medicine expanded elsewhere.

The takeover lasted about twelve hours. The next day, the New York Times ran the headline “Young Lords Seize Lincoln Hospital Building; Offices Are Held for 12 Hours.” Reporter Alfonso A. Narvaez wrote that protesters demanded “better health services and a greater voice in hospital operations,” noting that they “left the building without violence” after negotiations with city officials. When it came time to leave, some of the occupiers blended back into the hospital’s own churn — donning scrubs and stethoscopes to slip out past police and administrators, looking like just another cluster of staff.

Four months later, on November 10–11, 1970, activists returned, this time to force the creation of a detoxification program amid a heroin epidemic devastating the Bronx. The action was not simply militants demanding services for others. People in active addiction, hospital workers, and neighborhood residents together seized space inside Lincoln and established what they called the People’s Program — the foundation of what later became the Lincoln Detox Center.

Lincoln Detox, which began as the People’s Program following the November occupation and was later incorporated into the hospital system with city funding after negotiations with administrators, treated addiction not as an individual moral failure but as inseparable from poverty, racism, housing instability, policing, and economic neglect. It hired people in recovery as peer counselors. It offered childcare. It paired medical treatment with political education. It pioneered acupuncture protocols that would later spread nationally. At its height, it served roughly 1,600 people a month.

By the late 1970s, the program was reorganized and narrowed. Political education ended. Two staff members were fired. Twelve others, many of them associated with the Young Lords or the Black Panther Party, were reassigned elsewhere in the hospital system, shielded from dismissal by union and civil service protections but stripped of their roles inside Detox. Over time, services shrank further as the program was disciplined by the same institution it had forced to act.

Last week at Hostos Community College, a few blocks from Lincoln Hospital, former Young Lords, public health officials, historians, and harm reduction workers gathered in an auditorium to revisit that history. The event was a public symposium, part of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s “Healing ARC Project,” with ARC standing for Acknowledgement, Redress, Closure. The event was framed as an ongoing research and accountability process emerging from the NYC Board of Health’s 2021 declaration that racism is a public health crisis.

The first panel revisited the takeover and the birth of Detox, with the speakers consisting of South Bronx residents and Young Lords members who had taken part in the November 1970 hospital takeover, including Miguel “Mickey” Melendez, Vicente “Panama” Alba, and Walter Bosque del Rio. The men were older now, their memories ricocheting between street tactics and staffing charts, between who held which position in the program and how many detox beds they managed to secure. The second panel, focused on the present, made clear that the stakes are not merely archival.

Bosque del Rio, who came to Lincoln as a nursing student and ended up helping build the program’s acupuncture work, described how the place politicized him in real time. “I came for the summer,” he said, thinking he’d just volunteer and go back to school. “But I no longer wanted to be a nurse. I wanted to be a revolutionary.”

Redress

Near the close of the first panel, Alba, Bosque del Rio, and Melendez delivered a joint statement aimed at pinning down what “redress” should mean in practice, not just as a phrase that sounds good in a grant application. “While an apology acknowledges the injury,” they said, “it does not mitigate the loss without material redress.” They warned against a process that produces “closure” for institutions while leaving harmed communities materially where they started.

Historian Sam Roberts described Lincoln Detox as a rejection of what he called the long-standing American “false binary” between addiction as moral vice and addiction as medical disease. What Detox offered, he said, was something different: “a group of people who have their own agency, their own political subjectivity, their own decision-making processes.”

Jules Netherland of the Drug Policy Alliance reminded the audience that “we never ended the war on drugs for people of color,” even when national rhetoric shifted during the opioid crisis. The infrastructure of enforcement remained. Redress, she argued, cannot be race-neutral in a society structured by racialized disinvestment.

Tamara Aponte Santiago, cofounder of Bronx Móvil, a community-based harm reduction organization that operates mobile outreach services across the South Bronx, pointed to the geography of today’s crisis. Bronx Móvil distributes naloxone, provides overdose prevention education, connects people to treatment, and delivers supplies directly to residents who often have little contact with formal health institutions. The geography of overdose has barely shifted. The same census tracts that fueled the 1970 occupation remain among the city’s most lethal.

Her participants, she said, are asking for an overdose prevention center in the Bronx.

“We need the full menu,” she added, meaning harm reduction, treatment, prevention, and housing support.

Hiawatha Collins of the National Harm Reduction Coalition pushed further. Community members must not be invited in after plans are written; they must be “at the beginning of the process.” And inclusion must be material. “Include them, hear them, pay them,” he said, and not at minimum wage.

The panelists’ proposals were concrete: reopen training infrastructure in the former Detox building now stewarded by South Bronx Unite; restore acupuncture training capacity lost when Lincoln Recovery Center closed; disaggregate public health data to better identify racialized harm; fund overdose prevention centers in the Bronx; and protect harm reduction workers with stable, adequately paid positions.

Recent neighborhood-level data show that areas in the South Bronx and East Harlem continue to record some of the highest fatal overdose rates in New York City, far above the citywide average. In other words, the crisis that fueled Lincoln Detox has not receded.

Mayor Mamdani’s Assessment

The Healing ARC project did not originate with Mayor Zohran Mamdani’s administration, but it now unfolds within it. For a mayor who has framed his politics around expanding public services and confronting structural inequities, Lincoln presents an opportunity to convert institutional acknowledgment into budgetary commitment, to move from recognition to redistribution. If his administration believes in public provision as more than rhetoric, Lincoln offers something unusually concrete: a public hospital under city control, neighborhoods with documented overdose disparities, and a record of exactly how services were once expanded.

The ARC process has produced something rarer than an apology: spreadsheets, budget trails, internal memos, documentation showing when funding was cut, when services were narrowed, and who signed off. The question now is whether that record translates into appropriations: fully funded peer-led recovery programs embedded in public hospitals, permanent overdose prevention centers in the Bronx, community advisory boards with binding authority, and durable employment protections for workers.

The U-Haul and the scrubs, the daring occupations of a hospital by the residents it failed to serve, were long ago. But whether the South Bronx receives the sustained resources it has demanded for more than half a century will determine whether Lincoln remains merely a radical memory, or becomes a blueprint finally implemented.