America’s Schools Are Overheating as Climate Change Cranks the Thermostat

Our resource-starved public education system is not equipped to handle the increasingly extreme heat, condemning students and teachers to sweltering classrooms. New school infrastructure is an urgent priority if we want to have a functional education system.

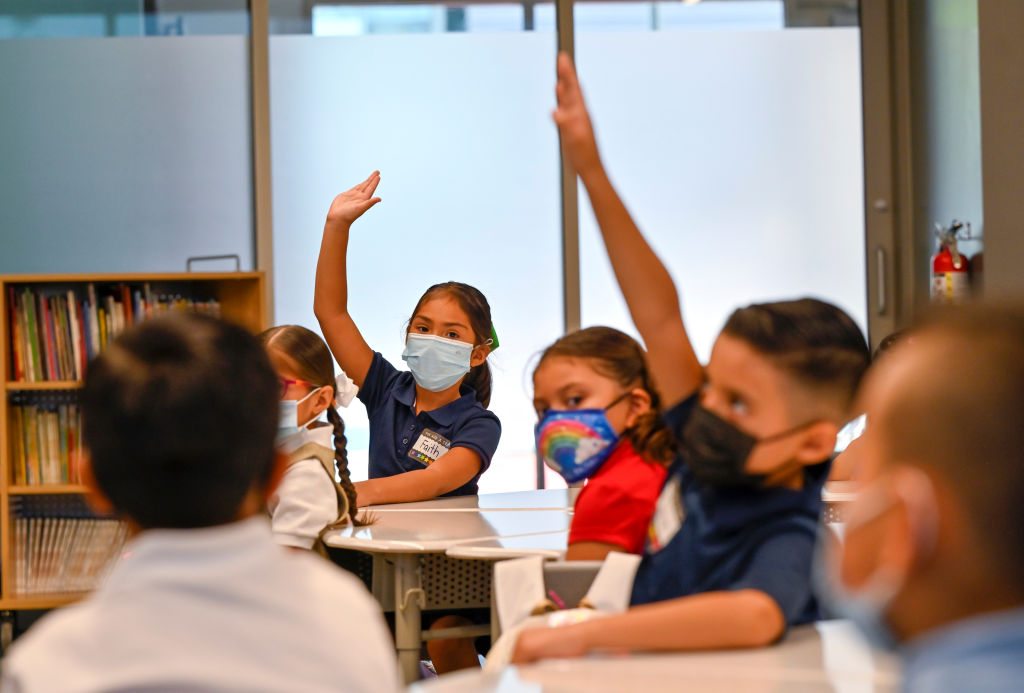

Overheated classrooms make it virtually impossible for students to engage in meaningful scholarship. (Jeff Gritchen / MediaNews Group / Orange County Register via Getty Images)

Lauren Nickell, an educator in Boston Public Schools, was frustrated with her district for making students attend school in an “inhumanely” hot building during last spring’s heat wave. Facing pressure from her union, the district finally sent a truckload of box fans. But there was a catch: Nickell and her colleagues were warned not to get attached to the fans because they would need to return them the following week.

Most people who have worked in public schools, particularly in resource-starved districts, can think of similarly absurd scenarios: sweltering classrooms with windows that are painted shut; ancient heating systems that blast warm air on sunny May afternoons; or how about the Philly elementary teacher who, after crowdfunding a window AC unit, learned that his classroom’s aging electrical wiring would not support it. My memories of teaching while hot mostly involve teenagers shutting down or flying off the handle, their uncomfortably high body temperatures magnifying every adolescent frustration.

Pandemic aid aside, the federal government has not seriously invested in public school infrastructure for nearly a century — despite the fact that schools represent the second-largest infrastructure sector in the United States. While the Department of Education assumes a small but meaningful role in combating the massive inequities we see in our education system, this role has not included fixing the infrastructural issues that cause poor and minority kids, especially, to attend classes in dilapidated, unsafe buildings. The American Society of Civil Engineers gives our school facilities a D+ grade, owing to problems that range from irksome to developmentally hazardous or deadly (leaded drinking water, toxic mold, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), friable asbestos, mercury vapors — the list goes on and on). Due to decades of underfunding, school districts have huge backlogs of essential capital expenses they simply cannot afford.

Stuffy classrooms are just one piece of this overwhelming picture, but as climate change bathes more and more of the calendar in extreme heat, they are the hardest piece to ignore. This fall, students in major urban districts across the United States were once again sent home because their school buildings became dangerously hot. In Columbus, Ohio, things got so miserable that the teachers union had to go on strike for air conditioning. When schools do not dismiss during heat waves, students can suffer in rooms that exceed eighty or even ninety degrees. Solving this problem is an urgent priority if we want to have a functional education system.

Fossil Fuel Use Overheated Our Schools

Historians say summer vacation was set up to protect children from oven-like conditions in school buildings during the warmest months of the year. With cold winters in mind, schools in large portions of the United States were designed to trap as much heat as possible. Researchers estimate that only about 40 percent of US public schools have air conditioning.

But weather patterns have changed. According to Hotter Days, Higher Costs: The Cooling Crisis in America’s Classrooms, a 2021 report from the Center for Climate Integrity, thousands of districts that did not experience excessively warm spring and fall weather in 1970 have begun to see three or more weeks’ worth of school days over 80 degrees — a direct consequence of fossil fuel–driven global warming. In warmer regions, schools now require additional capacity to combat extreme heat. The report’s authors calculate that by 2025, the vast majority of all US public school students will have been impacted in one way or another by their district’s climate-related heating, ventilation, and cooling (HVAC) costs.

In addition to the more mundane irritations (sweat-stained quizzes, slippery desks and chairs, unpleasant odors that linger in the classroom), overheated buildings pose real health risks for the people who learn and work in them. Children’s bodies overheat much more quickly than adults’ do, and kids are generally bad at remembering to drink water and remove layers as they warm up. Every year, student athletes die from heat stroke. Chronically overheated environments are especially dangerous for students and workers with health conditions like asthma and pregnancy, and for the disproportionately older school support staff who labor in sweltering kitchens and gyms. And for those abstaining from fluids in observance of Ramadan or other religious customs, sitting in a ninety-degree classroom can be excruciating.

Hot classrooms also make it virtually impossible for students to engage in meaningful scholarship. Multiple studies have demonstrated that cumulative heat exposure inhibits cognitive skill development and is associated with decreased scores on standardized tests. In one study, New York City students were more than 12 percent more likely to fail their high school exit exams if they took them on a 90 degree day relative to a 72 degree day. Importantly, subsequent research suggests this effect is canceled out by working air conditioning. A good HVAC system, in other words, can literally mean the difference between getting a diploma and not graduating.

Because overheated schools disproportionately impact black and Hispanic students (and, evidently, harm them more), the authors of one study estimate that cumulative heat exposure may be responsible for up to 13 percent of what is known as the racial achievement gap. “It’s absurd to me,” Los Angeles high school teacher Sandra Ruiz-Chau told Jacobin, “that we’re in Los Angeles in 2022, and depending on what zip code your school is in, you may not have working AC.” Rather than throwing more money at educational technology (edtech) companies promising to boost outcomes for disadvantaged kids, we should focus on making school buildings healthy and habitable for everyone.

Footing the Bill

COVID-19 brought schools’ serious ventilation problems into popular awareness, and federal pandemic aid injected an unprecedented amount of cash into districts across the United States. So why are we still seeing reports of children coming home from school with heat-induced headaches and bloody noses?

The answer is that our school facilities are egregiously underfunded, due in large part to declining state-level investments since the Great Recession. As a share of the economy, state capital funding for schools dropped 31 percent between 2008 and 2017. According to some estimates, public school infrastructure now falls short of needed funding by about $85 billion every single year. So even when pandemic aid money was used for facility upgrades, air conditioning was in competition with gargantuan lists of other old and new infrastructure needs.

Most people recognize that, as the authors of Hotter Days, Higher Costs write, keeping classrooms at tolerable temperatures “is a bare minimum requirement for a functional education system” (emphasis added). Parents who might spar over masking or pronouns can almost certainly agree that kids should not have to sweat through their lessons. But districts simply do not have the money to realize this goal, especially given the exorbitant costs of parts and services under inflation. The authors of the report calculate that mitigating the effects of fossil fuel–driven climate change on classroom temperatures will cost US schools over $40 billion to install new equipment, plus $415 million to upgrade existing equipment, by 2025 — and $1.5 billion annually for new maintenance costs. Two districts — New York City and Chicago — will need more than a billion for HVAC installation alone.

New York and Chicago, along with other urban districts, have thus far opted to install window air conditioning units rather than tackle the complexity of retrofitting older buildings to support central HVAC systems. While this approach may be cheaper and easier up front, it is far more wasteful (and less effective) in the long run. This example illustrates how schools, being on the front lines of climate change, are now at a crossroads. Facing severe budgetary constraints, they can continue scrambling to provide last-resort solutions that are inefficient and inadequate. Or they can invest in the thoughtful planning and state-of-the-art equipment needed to limit both future suffering and future emissions. But where will the money come from?

Well, there’s a great case to be made for consistent federal funding for school infrastructure. State and local governments have limited revenue streams and are therefore not able to raise the astronomical sums districts require for modernized facilities. It’s difficult to mount any argument against safer school buildings, and yet the issue has not been treated seriously by either party.

The authors of Hotter Days, Higher Costs have another idea: make fossil fuel companies foot the bill as school districts adapt to rising temperatures. “These costs,” they write, “have been thrust on school systems by polluters who knew their products would cause climate change, and with it, enormous damage and costs to society, but who then lied about it in order to protect their profits.”

Schools are places where greed-driven injustices like poverty and climate change become highly visible. The perpetrators of these injustices have built a movement around forcing the education system to repackage systemic harm as individual failure: teachers not teaching enough, students not scoring highly enough. But when it comes to overheated classrooms, it’s not hard to see what’s really going on.