How the Mexican Revolution Made John Reed a Red

John Reed’s thrilling dispatches from the front lines of the Mexican Revolution could have made him a pop culture celebrity. Instead, the experience made him a committed socialist.

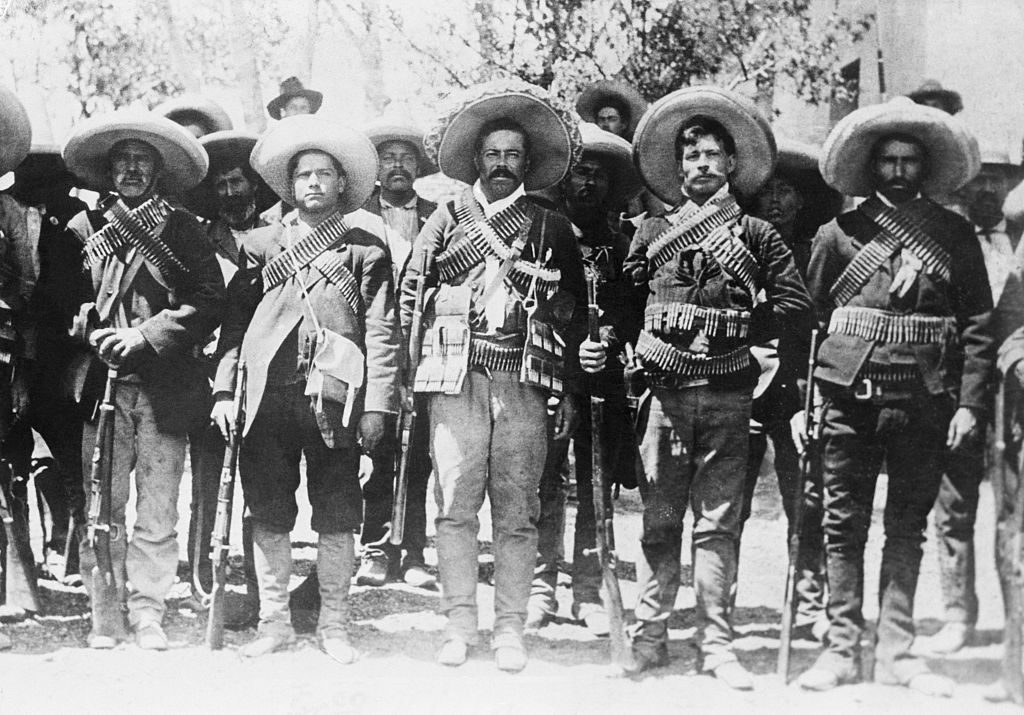

Journalist John Reed, author of Insurgent Mexico and Ten Days That Shook the World, in 1914. (Getty Images)

In 1913, American journalist John Reed was embedded with a ragged band of revolutionary soldiers in Mexico. Few of them possessed a complete uniform. Some were shod only in cowhide sandals. They were camped out in northern Durango, sleeping on the tiled floors of an hacienda whose wealthy owner had been expelled by revolutionary forces.

But now the counterrevolutionary colorados were coming to kill them all.

Reed, known to his friends back home as Jack and his friends here in Mexico as Juan, was twenty-six years old, boyish and spirited, quick-witted and usually self-possessed, though at this moment he was scared out of his mind. Bullets were already flying, sending mules and men scattering into the Chihuahuan Desert. The peasants of the hacienda took cover in their modest adobes and prayed. One soldier, face blackened with gunpowder, galloped past crying that all hope was lost.

Reed escaped on foot with a small detachment. They fled down a narrow path through the chaparral, the colorados hot on their heels. The fourteen-year-old fighter at his side was trampled and shot. Reed tripped on a mesquite branch and tumbled into an arroyo, where he lay listening as the colorados argued about which way he’d gone. He remained motionless as their voices faded, and eventually lost consciousness. When he woke, he could still hear gunfire near the Casa Grande — the sound, he later learned, of the colorados shooting corpses for good measure.

He snuck down the arroyo away from the action, but was soon startled by a stranger in his path. The stranger had a bloody handkerchief wrapped around his head and carried a green serape over his arm. His legs were caked in blood from the espadas, the spiny cacti that covered the desert floor. Reed couldn’t tell which side of the fighting he was on. The man beckoned, and Reed saw no choice but to follow him.

They crested a hill and the stranger gestured to a dead horse, its stiff legs poking up in the air. Nearby lay the body of its rider, disemboweled. Reed turned to look at the man with the green serape, and saw that he was holding a dagger. The dead one was a colorado. Together they buried him, covering the shallow grave with rocks and fastening a cross out of mesquite branches. When they were finished, the man with the green serape pointed Reed to safety.

The year before, Reed had been in Portland, Oregon, wandering the streets alone at night, lost in unhappy thought. He’d come home for his father’s funeral and to settle his family’s financial affairs. Reed was descended from great wealth, but the fortune had mostly vanished. Gone, too, were the gaiety of Reed’s Harvard days and the novelty of the bohemian writer’s life in New York. Reed was adrift, uncertain what kind of life he would live, what kind of man he would become.

Less than a decade later, Reed died in Russia, a Bolshevik, a traitor to his country and his class. His remains lie now at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Moscow. His biography is immortalized in Warren Beatty’s acclaimed 1981 epic film Reds. And while the film vividly depicted many of the important episodes from his colorful and storied life, with the exception of a brief shot of Beatty scrambling through the Chihuahuan Desert, it overlooked an important one: John Reed’s time among the combatants, including Pancho Villa himself, during the Mexican Revolution.

It was in Mexico that Reed not only indulged his taste for action and adventure but also witnessed the lows of degrading poverty, the highs of revolutionary hope, and the lengths the international capitalist class would go to in order to prevent egalitarian social transformation.

The night before the siege on the hacienda, a proclamation from the governor of Durango was read aloud to the soldiers in their sleeping quarters. It said:

Considering . . . that the rural classes have no means of subsistence in the present, nor any hope for the future, except to serve as peons on the haciendas of the great landowners, who have monopolized the soil of the state. . . .

Considering . . . that the rural towns have been reduced to the deepest misery, because the common lands which they once owned have gone to augment the property of the hacienda, especially under the dictatorship of [President Porfirio] Díaz, with which the inhabitants of the state lost their economic, political, and social independence, then passed from the rank of citizens to that of slaves, without the government being able to lift the moral level through education, because the hacienda where they lived is private property. . . .

Therefore, the government of the state of Durango declares it a public necessity that the inhabitants of the towns and villages be the owners of agricultural lands.

“That,” one soldier said to Reed, “is the Mexican Revolution.” The next day, rather than flee, the soldier stayed at the Casa Grande, where he died trying to fend off the colorados in vain.

The Making of “Storm Boy”

John Reed was born in 1887 in Portland, Oregon, which was then dominated by pioneer capitalists from the East. As lumber barons passed by in elegant carriages, the city’s workers trudged down muddy avenues, hazardously strewn with stumps and felled trunks from the clear-cut forest, to perform grueling manual labor or to drink and gamble in the city’s vice dens.

The apparent moral laxity of Portland’s working class was of great concern to the members of the Arlington Club, an exclusive institution founded twenty years earlier to promote social and professional solidarity among local elites. One of the Arlington Club’s founders was Henry Green, John Reed’s maternal grandfather who had come from upstate New York, where he had established a successful mercantile enterprise. Henry and his wife, Charlotte, became pillars of Portland high society.

Their daughter, Margaret Green, married C. J. Reed, another ambitious young businessman from upstate New York, and they started their family at the Green estate. John Reed later described the house as a “lordly grey mansion” surrounded by a dense forest of fir trees. His grandparents lived with “Russian lavishness,” their residence decorated ornately with elaborate textiles and exotic artifacts acquired in the course of their world travels. Though nestled in the emerald Willamette Valley, worlds away from the Chihuahuan Desert, the opulent estate had much in common with the haciendas whose expropriation was a principle aim of the Mexican Revolution.

John Reed was not an especially happy child. A kidney condition kept him indoors more often than not. At first, he was confined to the Green estate, where he was looked after by Chinese servants who regaled him with mesmerizing tales of their distant homeland. Later, when the family moved off the estate, he kept himself company with books. He was timid around other children, once even paying a neighborhood bully a quarter not to beat him up.

C. J. Reed’s business had never been as successful as Henry Green’s, and as Charlotte Green spent the remainder of her late husband’s fortune, John’s parents found themselves unable to replenish the well. They were hardly poor, but neither could they maintain their former lifestyle. Even so, C. J. put together the money to send his son to boarding school in Morristown, New Jersey, with the express intention of getting the boy into Harvard.

In Morristown, John Reed flourished. He was finally in good physical health, and discovered that a certain reputation preceded him as a Westerner. The other boys, all preppy Northeastern blue bloods, expected a wild man from the rugged frontier. Having consumed a great many adventure novels throughout his isolated childhood, he was eager and able to play the part. Overnight, the once sullen child became a popular young man with a knack for playfully challenging authority. Somewhere along the way he picked up the nickname “Storm Boy,” evoking a roguish vitality and inclination to misbehave that were latent throughout his subdued and sheltered childhood.

At Harvard, Reed developed a new awareness of and sharp distaste for excessive wealth. He was aghast to learn that some of his new classmates were given $15,000 a year allowance, close to $400,000 a year today. Reed’s desire to be liked was overpowered by his irrepressible contempt for Harvard culture and custom. “The more I met,” he wrote later of his Harvard peers, “the more their cold, cruel stupidity repelled me. I began to pity them for their lack of imagination and the narrowness of their glittering lives — clubs, athletics, society.”

Reed lampooned Harvard every chance he got, frequently pulling pranks that drew the ire of campus authorities. The college even revived an archaic form of punishment just for Reed, a type of mandated confinement. The writer and intellectual Walter Lippmann, who attended Harvard with Reed, wrote that he “came from Oregon, showed his feelings in public, and said what he thought to club men who didn’t like to hear it. Even as an undergraduate he betrayed what many people believed to be the central passion of his life, an inordinate desire to be arrested.”

While he attended a few Socialist Club meetings, Reed’s campaign to undermine Harvard’s self-seriousness was animated more by his hatred of aristocratic convention than any political vision for a classless society. That changed after Reed graduated and moved to New York City to try his hand at writing, at first with little success.

In search of suitable subject matter and a good time, he spent his evenings in disreputable establishments, the kind his grandfather’s Arlington Club had disapproved of in Portland, chatting up patrons and following them out into the city to find out where and how they lived. One story that emerged from this process was a sincere and humanizing portrait of a prostitute Reed met out on the town. Editors across the city agreed it was excellent, but all found it too morally ambiguous to publish.

When Reed was back in Portland, mourning the death of his father and brooding over the stagnation of his life in New York, he received word that a socialist magazine, The Masses, had agreed to publish his story. Thereafter, Reed wrote for The Masses, and his interests and perspective began to align with the mission of the publication.

At a party thrown by the avant-garde artist and socialite Mabel Dodge Luhan, Reed met “Big Bill” Haywood, who had come to gather support from urban progressives for a textile workers’ strike in Paterson, New Jersey. Reed followed Haywood to Paterson, and entered a new phase of his life altogether.

Reed’s experience there in New Jersey transformed him into two things at once: a journalist and a socialist. He not only covered the 1913 Paterson strike for The Masses but was famously jailed alongside the strikers, an experience he recounted colorfully and movingly in his reporting. Before long he had joined the International Workers of the World and was helping to organize strike solidarity efforts.

At the same time, Reed proved himself to be a captivating writer and a reporter of unusual courage, one willing to get right in the middle of things instead of poking around the perimeter. When editors at the Metropolitan hired him to report on the Mexican Revolution, they did so because they suspected he’d find his way to the center of the action like a moth to a flame. And they were right.

Land and Freedom

There were 15 million people living in Mexico at the beginning of the revolution. Over the course of the conflict, an estimated 1 million were killed, and roughly 2 million more migrated to the United States fleeing violence.

John Reed could easily have lost his life, traveling as he did with embattled armies at the peak of unrest in 1913 and 1914. Instead, he survived and published a riveting book of reportage, Insurgent Mexico, that served as the prototype for Ten Days That Shook the World, his famed account of the Russian Revolution. His experience in Mexico cemented his status as a leading American journalist covering armed conflicts at home and abroad. It also introduced him to new depths of deprivation and exploitation, and impressed upon him the need for international socialism.

The story of the Mexican Revolution begins with Porfirio Díaz, who in the mid-nineteenth century had been a leader of the country’s Liberal faction, proponents of democracy and free-market capitalism, as they battled with Conservatives, who preferred a more traditional hierarchical social arrangement steered by a monarch and the Catholic Church. Díaz became president in 1876, and over time shed his liberal commitment to political democracy. The turn of the century came and went, and he was still in power.

As dictator, Díaz exerted tight control over Mexican politics while his domestic army of federales and countryside police force of rurales kept the Mexican people in line. But while he reneged on his political promises, Díaz was firm in his commitment to capitalism. The Porfirian regime bent over backward to satisfy Mexico’s wealthy landowners, the hacendados, as well as open up the country to foreign investors, particularly American but also British and French, who dug mines and oil wells and commandeered vast plantations.

With Díaz’s support, the domestic and foreign business elite profited handsomely as rural subsistence farmers and small proprietors were dispossessed of their modest individual and collective holdings. Mexico’s peasants were tethered in semifeudal fashion to the rural haciendas, or compelled to toil in hazardous conditions in fields and mines for low pay, often as precarious informal day laborers. Some indigenous people were even sold into slavery.

A first challenge to the Díaz dictatorship, led by the Flores Magón brothers, was crushed in 1906. But it left a lasting impression, binding together two demands in the minds of the Mexican people: political democracy, on the one hand, and, on the other, agricultural reform, specifically the end of the repressive hacienda system and the redistribution of the land itself to the people who worked it. The revolution to come would summarize these two demands with the slogan tierra y libertad — land and freedom.

The revolution finally arrived when Francisco Madero, liberal son of a wealthy family that owned not only land and mines but also factories, mounted a bid for the presidency, a betrayal for which Díaz had him arrested and imprisoned. The conflict was intra-elite at first: Madero represented an enterprising segment of the capitalist class, more modern than the old-school hacendados. But Madero’s appeals for democracy had wide appeal. Makeshift armies of peasants and workers desperate for change rallied to his cause, spearheaded by a new generation of leaders who seemed to come out of the woodwork.

Within a year, the Díaz regime was finished and Madero was in power. But the revolution was far from over. Madero assumed the presidency but changed very little, keeping most administrative structures and even personnel in place. His attempts to appease disgruntled porfiristas met with little success, for there were right-wing rebellions anyway. Meanwhile, the left that had swept Madero to power was dismayed by his apparent disinterest in pursuing any kind of ambitious reform agenda.

Emiliano Zapata, the commander of an army of peasants in the south of Mexico and the most ideological and radical of all the new leaders, declared that the revolution was still on so long as the land reform question remained unaddressed and poverty unalleviated. “La tierra es para el que la trabaja,” went the zapatista slogan. “The land is for those who work it.”

Pascual Orozco’s army of miners, railroad workers, and farm laborers in the North also turned on Madero, echoing calls not just for the expropriation of the haciendas but also better working conditions and protections for labor unions.

The Madero government’s apparent weakness in the face of these left-wing worker and peasant rebellions spooked domestic and international business elites and their allies in government. To solve this problem, Henry Lane Wilson, US president William Howard Taft’s ambassador to Mexico, played a leading role in orchestrating a coup in which Madero was murdered and a traitorous general, Victoriano Huerta, assumed the presidency. It was a playbook the United States would refine to the point of near perfection over the next century.

After Madero’s assassination in 1913, all hell broke loose. Huerta successfully offered Orozco some concessions on workers’ rights in exchange for his allegiance, but Zapata — unyielding on the question of land reform — was set against him. So too was Pancho Villa, the leader of the largest revolutionary army in the country, the mighty División del Norte. Though Villa’s personal sympathies lay with the poor, he was at least on paper working for another general, Venustiano Carranza, a less radical leader who had taken up the maderista cause against Huerta.

It was at this chaotic juncture, when the roster of important names grew too long to keep straight, that John Reed crossed the border, passing from the Texas town of Presidio into the Mexican town of Ojinaga. The latter had been besieged five times since the start of the conflict three years earlier. Of war-torn Ojinaga, he wrote:

The white, dusty streets of the town, piled high with filth and fodder, the ancient windowless church with its three enormous Spanish bells hanging on a rack outside and a cloud of blue incense crawling out of the black doorway, where the women camp followers of the army prayed for victory day and night, lay in hot, breathless sun. . . . Hardly a house that had a roof, and all the walls gaped with cannon-shot.

Reed understood immediately that while the proliferation of armies and constant shifting of loyalties made the conflict difficult to follow, it was in fact simple to understand. “It is common to speak of the Orozco revolution, the Zapata revolution and the Carranza revolution,” he wrote. “As a matter of fact, there is and has been only one revolution in Mexico. It is a fight primarily for land.”

Opening the Closed Fist

As the country emerged from Díaz’s bourgeois dictatorship, peasants and working people in Mexico lacked a political vehicle to cohere and advance their interests. The closest thing was Zapata’s army in the South, which was clear about its aims: not only political democracy and land reform but also universal public lay schools, which put it in conflict with the Catholic Church that controlled education, and the nationalization of Mexico’s natural resources, which put it in conflict with both domestic and international capitalists.

But in the North, there was no army whose political goals were quite so explicit. Pancho Villa was known as Mexico’s Robin Hood for his eagerness to redistribute wealth and land, often acquired through ruthless acts of expropriation and cunning feats of banditry. But he acted in coalition with others whose inclinations were notably less redistributionist, and besides, whatever his class sympathies, Villa was more a military leader than a political one. And so the workers and peasants in the North grafted their own hopes for radical social transformation imperfectly onto the muddled revolution that was already underway.

Reed embedded early on with a revolutionary battalion under the command of General Tomás Urbina, whose inner circle displayed the range of perspectives at the top of the revolutionary military hierarchy. A major told Reed that the revolution “is a fight of the poor against the rich. I was poor before the revolution, and now I am very rich.” But a captain told Reed, “When we win the Revolución it will be a government by the men — not by the rich. We are riding over the lands of the men. They used to belong to the rich. But now they belong to me and to my compañeros.”

Later on, Reed was greatly impressed by General Toribio Ortega, “by far the most simple-hearted and disinterested soldier in Mexico,” who told Reed,

We have seen the rurales and the soldiers of Porfirio Díaz shoot down our brothers and our fathers, and justice denied to them. We have seen our little fields taken away from us, and all of us sold into slavery, eh? We have longed for our homes and for schools to teach us, and they have laughed at us. All we have ever wanted was to be let alone to live and to work and make our country great, and we are tired — tired and sick of being cheated.

All across northern Mexico, Reed met both rank-and-file soldiers and pacíficos — those who stayed out of the fighting — who articulated radical interpretations of the revolution’s aims. The night before the hacienda battle, Reed witnessed a soldier composing a ballad that contained verses such as “The rich with all their money, have already got their lashing. . . . Ambition will ruin itself, and justice will be the winner.” Reed came across a pacífico, a gentle man whose body was wasted from malnutrition, who told him, “The Revolución is good. When it is done we shall starve never, never, never, if God is served.”

On one stretch of road, Reed came across two goat herders who shared their fire and offered shelter, one a hunched and wrinkled old man and the other a tall, smooth-skinned youth. As they spoke about the revolution, the young man’s voice rose with passion. “It is the rich Americans who want to rob us, just as the rich Mexicans want to rob us,” he said. “It is the rich all over the world who want to rob the poor.”

A few more words were exchanged and then the youth said, “For the years of me, my father, and my grandfather, the rich men have gathered the corn and held it in their clenched fists before our mouths. And only blood will make them open their hand to their brothers.” Moved by this encounter, Reed wrote:

Around them stretched the desert, held off only by our fire, ready to spring in upon us when it should die. Above the great stars would not dim. Coyotes wailed somewhere out beyond the firelight like demons in pain. I suddenly conceived these two human beings as symbols of Mexico — courteous, loving, patient, poor, so long slaves, so full of dreams, so soon to be free.

The Dream of Pancho Villa

John Reed wanted an audience with Emiliano Zapata, for whom he had complete admiration, calling him, in a letter to his editor, “the great man of the Revolution . . . a radical, absolutely logical and perfectly constant.” The meeting proved impossible, but the Metropolitan was equally if not more pleased when Reed was able to secure an audience with the infamous Pancho Villa.

Of course, riding with Villa meant tempting fate, as the general was involved in heavy fighting and never far from the front lines. But Reed leapt at the opportunity to put his life in danger in order to capture Villa’s essence, which was precisely why the Metropolitan had hired him.

Villa had been intensely demonized by the American press, but Reed saw things differently, viewing Villa as a man of the people and friend to the poor. Villa promised that there would be “no more palaces in Mexico” after the revolution, and often expressed his love for the people with sayings like “The tortillas of the poor are better than the bread of the rich.” He demonstrated his class allegiances in action many times, seizing money and property from the rich without remorse and either giving it directly to the poor or putting it to use for the revolutionary cause. Villa was reviled by the Mexican bourgeoisie, whereas the peasants composed ballads about him.

But Reed also observed that Villa’s strengths were not political. He had lived as an outlaw prior to the revolution, and was illiterate until a stint in prison for his role in supporting Madero gave him the opportunity to learn to read. He had some idea, which he expressed vaguely to Reed, that after the revolution the state would establish large enterprises that would both employ everyone and produce all the things people needed. But Reed once asked him what he thought of socialism, to which Villa responded, “Socialism — is it a thing? I only see it in books, and I do not read much.”

Villa’s great talent was instead his instinctive military dexterity. Reed compared his style of fighting to Napoleon’s, naming among his advantages “secrecy, quickness of movement, the adaptation of his plans to the character of the country and of his soldiers, the value of intimate relations with the rank and file, and of building up a tradition among the enemy that his army is invincible, and that he himself bears a charmed life.” Reed saw Villa as an autodidactic military genius, capable of viewing the entire revolution in all its complexity from a high perch and making swift decisions based on gut feeling that proved consistently correct.

When Reed asked Villa whether he wanted to become president of Mexico, Villa answered frankly, “I am a fighter, not a statesman.” Knowing the Metropolitan would be unsatisfied with the simplicity of the response, Reed was compelled to ask several more times. This annoyed Villa, who told Reed that if he asked the question again, he would be “spanked and sent to the border,” and walked around for several days thereafter telling everyone with amusement about the chatito (pug nose) who wouldn’t drop the issue. Nonetheless, Villa liked Reed enough to spend plenty of time with him in private, and to write him an all-access pass to use the railways and telephones throughout Chihuahua free of charge.

The Pancho Villa in Insurgent Mexico is great fun. He never drank or smoked, but he loved to dance. He sent his own roosters into the cockfighting pit every afternoon at four o’clock. If he had extra energy to burn, he would sometimes check in at a nearby slaughterhouse to see if they had any bulls he could fight. He was a middling matador, “as stubborn and clumsy as the bull, slow on his feet, but swift as an animal with his body and arms.” If the bull knocked him with his horns, Villa would lunge at it and begin to wrestle, prompting his men to intervene.

“The common soldiers adore him for his bravery and his coarse, blunt humor,” Reed wrote admiringly. “Often I have seen him slouched on his cot in the little red caboose in which he always traveled, cracking jokes familiarly with twenty ragged privates sprawled on the floor, chairs and tables.”

This caboose was indeed a train car: when Villa sacked the city of Torreón for the first time, he took command of the northern Mexican railways, and thereafter his army traveled both by horse and by train. In addition to his caboose, there were hospital cars, water cars, cannon cars, and even repair cars whose purpose was to mend engines and broken segments of track, sometimes in the heat of battle.

The revolutionary armies started haphazardly, with no commissaries or any formal means to provide for the daily care of soldiers, from cooking to nursing to washing and mending clothes. So from the beginning, women called soldaderas had traveled with Villa’s army, caring for their enlisted husbands with their children in tow. Whole families crisscrossed the desert with Villa, first on foot and then by rail. Soldaderas also took up arms, though most spent their time cooking tortillas and big bowls of chile and hanging laundry from makeshift clotheslines atop the train cars. Without them, the whole operation would have fallen apart.

Reed wrote some of his most rousing passages in Insurgent Mexico about his time on the trains with Villa’s soldiers and soldaderas. Huerta’s counterrevolutionary government was unstable, his enemies were legion, and his reign was coming to a close. Reed was with the División del Norte as it advanced on Torreón for a second time, the spectacular guerrilla trains snaking through the desert, carrying on their backs the dream of a new nation.

Daybreak came with a sound of all the bugles in the world blowing; and looking out of the car door I saw the desert for miles boiling with armed men saddling and mounting. . . . A hundred breakfast fires smoked from the car-tops, and the women stood turning their dresses slowly in the sun, chattering and joking. Hundreds of little naked babies danced around, while their mothers lifted up their little clothes to the heat. A thousand joyous troopers shouted to each other that the advance was beginning . . .

A War Without End

As charmed as John Reed was by Pancho Villa, he was equally unimpressed with his boss Venustiano Carranza. Reed felt that Carranza had contributed little to the revolution, hiding out in the west at the peak of the military campaigns against Huerta’s forces. He met Carranza once, and found him both pompous and vacant, devoid of Zapata’s ideological commitment and of Villa’s dynamism and warm feeling for the Mexican people.

In his absence, Carranza had left Villa to make all military decisions and negotiate with foreign powers alone. Villa, thinking characteristically in military rather than political terms, had accepted aid from the Americans, who had already turned on Huerta, much as they had turned on Madero before him. After Huerta had fallen, the United States turned on Villa in short order. This was predictable: after all, the Americans’ primary objection to Huerta, as with Madero, was that he couldn’t control the peasant and worker factions commanded by Villa in the North and Zapata in the South.

With Huerta out of the picture — Villa’s second advance on Torreón having been decisive in his downfall — Carranza moved to establish a provisional government. Its first order of business was to restore the confidence of business leaders at home and abroad. Thus began a new phase of the revolution: Zapata and Villa versus Carranza, a moderate liberal who had never been particularly interested in expropriation and redistribution to begin with. Villa suffered a devastating military defeat in 1915. Zapata was assassinated in 1919. By the end of the decade, the revolution’s most radical formations were extinguished.

But though the mighty proletarian and peasant armies of the Mexican Revolution were crushed by their erstwhile allies, their ideology persisted — including in the new government, despite Carranza’s opposition. Poverty and exploitation were not eliminated, but over the course of the next several decades, the hacienda system was successfully abolished, public schools were established across Mexico, protections for workers and labor unions were strengthened, and the oil industry was nationalized. The revolution was incomplete, but not without major victories.

Back home, John Reed received high praise for the articles that would eventually form the basis of Insurgent Mexico. Walter Lippmann wrote in a letter to Reed that his Mexican reporting was “undoubtedly the finest reporting that’s ever been done. It’s kind of embarrassing to tell a fellow you know that he’s a genius.” His editor at the Metropolitan told him that “nothing finer could have been written,” and the magazine advertised his articles with enormous photos of him as if he were already a celebrity. Mainstream magazines clamored to publish his work, and the invitations for lectures were endless. Reed could have become the most popular journalist in the country, if he wasn’t already.

Instead, when he got back to the United States, Reed could think of little else but injustice. He wrote articles urging against US intervention in Mexico and taking his fellow journalists to task for their uncritical recitation of the State Department line. He followed his nose to Colorado, where he reported on the Ludlow Massacre, in which twenty-five people were killed during a coal miners’ strike, including eleven children. His Ludlow reporting demonstrated an evolution in his writing, consisting not just of evocative observations but a detailed analysis of the circumstances leading up to and following the massacre, laying the blame at the feet of capitalists and their political allies.

After Ludlow, the Metropolitan sent Reed to Europe to report on World War I. The magazine had hoped for more swashbuckling, but Reed’s reporting from Europe had a darker color and harder edge to it. Storm Boy’s madcap sense of adventure and mischief had been replaced by horror, sorrow, and pointed anger at the international elites who orchestrated this meaningless war. While in Germany, Reed interviewed revolutionary socialist Karl Liebknecht about his opposition to the war, and came to agree with radical socialists in the United States and Europe that the war itself was a crime committed by the bourgeoisie against the international working class.

Back in the United States, he neglected to pursue mainstream writing gigs, instead writing anti-war articles for The Masses. When the United States entered World War I, Reed’s articles were censored. As a result, The Masses lost its funding and went out of print. Rather than put his head down and work on rebuilding his journalism career with more politically anodyne reporting, Reed sailed back across the Atlantic to witness and indeed participate in the Russian Revolution. He came back a Communist, and the rest is history.

That history is well known, at least by people who enjoy Academy Award–winning dramas. What’s less well known is the role of the Mexican Revolution in making John Reed the socialist he became. Insurgent Mexico was his ticket to stardom, but it was also his bridge to radicalism. When the two paths diverged, he took the latter. For when John Reed went to Mexico, he went to class war. And he never came back.