Anna Seghers, a Writer Who Defended the Wretched of the Earth

Born this day in 1900, Anna Seghers was one of Germany’s great modern writers, an internationalist and anti-fascist through the darkest hours in German history. Her works are a monument to the dignity of the oppressed.

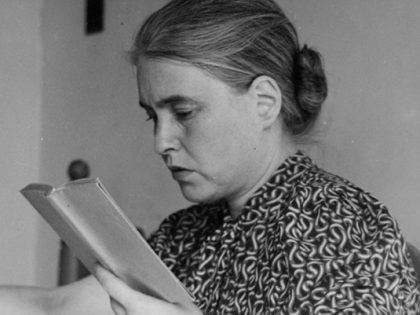

Anna Seghers in Paris, circa 1940. (Archive, Aufbau Verlag, Berlin)

Anna Seghers was one of Germany’s greatest writers — and 120 years since her birth, her works are still of enormous contemporary relevance. She chronicled the lives of the enslaved and oppressed, indigenous peoples, blacks and other people of color — those whom Frantz Fanon called “the wretched of the earth.” A lifelong internationalist, the opening lines of her 1944 novel Transit, about refugees escaping European fascism, could speak just as well to the dangers encountered by migrants crossing borders today.

Born at the turn of the twentieth century, Seghers hailed from Mainz, a city whose radical past stretches back to its Jacobin Club and its declaration of the first democratic state on German soil in 1792–93. Indeed, the spirit of Jacobinism would pervade Seghers’s life. This was visible both through the influence that Enlightenment and French revolutionary ideals had on her, and the way she realized them as a lifelong socialist.

Radical Origins

Born Netty Reiling, Seghers was the only child of Isidor and Hedwig. Her father owned an art and antiquities firm with his brother, while her mother — a founding member of the Mainz Jewish Women’s League — came from a renowned family of Frankfurt jewelers.

Seghers was raised in the traditions of Judaism and the Enlightenment. She later severed her religious ties, joining those whom Isaac Deutscher called “non-Jewish Jews,” like Baruch Spinoza, Karl Marx, Rosa Luxemburg, Leon Trotsky, and Sigmund Freud. Yet she never renounced Judaism’s ethical values — and her works abounded with allusions to Jewish history and Jewish themes.

In 1920, she enrolled at Heidelberg University, as one of few women students. There, she took courses in history, philosophy, sociology, sinology, and art history, and in 1924, she completed her doctoral dissertation on “Jews and Judaism in the Works of Rembrandt.”

In Heidelberg, Seghers came into contact with sociologist Karl Mannheim and László Radványi — both members of the Budapest Sunday Circle led by György Lukács and the poet Béla Balázs. Active in the Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919, after its defeat, these young intellectuals fled to Heidelberg via Vienna, to escape the anti-communist, antisemitic “White Terror.” From them, Seghers learned of the Sunday Circle’s philosophical discussions, their experiences during the Soviet Republic, and Lukács’s ethical principles and aesthetic theories — leaving a lasting influence on her work.

In 1925, Seghers married Rádványi, and they moved to Berlin, where they had two children. Radványi sought academic employment, but as a foreigner — to wit, a Jew from Eastern Europe — this proved impossible. From 1927, he directed the Berlin Marxist Workers’ School (MASCH). Its lecturers included Lukács, Balázs, Karl Korsch, John Heartfield, Wilhelm Reich, Walter Gropius, other Bauhaus members (supplying it with office furniture and classroom chairs), and even Albert Einstein, who gave two lectures on “What a Worker Must Know about the Theory of Relativity.”

Soon, MASCH students numbered up to twenty-five thousand per year. As ever more workers became unemployed, classes were also held in the back rooms of taverns — with the price of a glass of beer serving as tuition. Under Radványi’s leadership, the MASCH provided the model for thirty more schools in Germany as well as others in Zurich, Vienna, and Amsterdam. In 1933, when the couple were forced into French exile, he set up a similar but much smaller school in Paris.

Sensation

Seghers began her writing career as a modernist, influenced by the political avant-garde. Her first published story, “The Dead on the Island Djal” (1924), playfully depicting restless souls in a graveyard, is based on the diasporic fates of Lukács, Mannheim, and other Budapest Sunday Circle members. In 1927, she published “Grubetsch,” about a charismatic figure whose existential anarchism and unleashed libidinal energy lead to seduction and ruin. In 1928, she published The Revolt of the Fishermen, again evocative of events surrounding the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Along with “Grubesch,” this novella was awarded the Kleist Prize — the equivalent of today’s Booker Prize or National Book Award.

(Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Anna-Seghers-Archiv, Fotokartei, Nr. 08, Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von Anne Radvanyi)

Both works were signed with the genderless pen name “Seghers,” borrowed from a seventeenth-century Dutch artist — thus allowing reviewers to applaud the author’s “hard,” “masculine” prose. When Seghers appeared at the prize ceremony — turning out to be an attractive young woman — she became a media sensation. Under her subsequent pen name, “Anna Seghers,” the novella was soon translated into ten major languages. It was also the first of Seghers’s works to be made into a film, Vostanije Rybakov. As for the literary canon, The Revolt of the Fishermen takes its place with Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis and Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice as a masterpiece of German modernist prose.

The same year as her public debut, Seghers joined the German Communist Party and the League of Proletarian-Revolutionary Writers. She did this at a time when the working-class movement was at its peak in Europe and the United States, when peasant uprisings were underway in Asia and Latin America, and when writers and intellectuals allied themselves with communist parties worldwide.

Predictably, this also affected her literary reputation, as during a publicity tour in London in 1929. The Evening Standard reported that Seghers considered the English novel “rather tame,” her preference being the modern Russian school; that she shunned fashionable literary circles; and that as the guest of honor at a PEN-Club dinner, she gave an “intensely Communist speech.” Such skepticism notwithstanding, ten years later, the English poet John Lehmann called Seghers “the greatest woman artist of her generation on the Continent.”

For a Free Germany

Like other left-wing and Jewish writers, in 1933, Seghers was blacklisted by the Nazis — and her books burned. Fleeing to Paris, she became an active speaker and essayist within the anti-fascist movement. The fascist threat had already influenced her work: her first novel, The Wayfarers (1932), portrayed right-wing reaction from Poland to Italy and China; her second, A Price on His Head (1933), depicted Nazi gangs in Hesse six months before the Hitlerite takeover.

Politics pervaded Seghers’s writing. In 1934, she traveled to Austria to document the February workers’ uprising and trace the footsteps of socialist leader Koloman Wallisch, up till his eventual execution. The year 1937 saw the publication of her novel The Rescue, on the plight of unemployed Silesian miners; Walter Benjamin published an enthusiastic review the following year. In 1938–39, she wrote The Seventh Cross, about seven political prisoners escaping from a German concentration camp; only one evades capture, thanks to the underground Communist resistance and the support of ordinary citizens. The book’s publication in Europe was, however, prevented by the outbreak of war on September 1, 1939.

Rounded up by the French as an “enemy alien,” in April 1940, Radványi was incarcerated in the notorious Le Vernet concentration camp; when the Germans marched on Paris in June, Seghers and her children joined hundreds of thousands fleeing south. Turned back by the Wehrmacht, they spent the summer in hiding in the French capital. In September, they made the dangerous illegal crossing to the unoccupied zone and found lodging near Le Vernet, in Pamiers. From there, Seghers made frequent trips to Marseille to secure travel papers and visas, and finally, in March 1941, the family departed Marseille on the Capitaine Paul-Lemerle. Fellow passengers on this cargo and refugee ship included the surrealist and Trotskyist André Breton and the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, who described the precarious voyage in his Tristes Tropiques. After detentions in Martinique, Santo Domingo, and Ellis Island, in late June, the family arrived in Mexico, where they were given asylum.

Around this time, Seghers began work on Transit. Based on her recent experiences in Marseille, the novel depicts the desperate, often failed, flight of Jews and others from Europe. Whereas the plot is related by a seemingly indifferent narrator — a man not unlike Rick Blaine in Casablanca — the figure that haunts its pages is the writer Weidel, who commits suicide in Paris during the German invasion. Seghers based him on Ernst Weiss, a Moravian-born Jewish writer whom she had known in Paris before his suicide in June 1940. This choice was not an arbitrary one. Although a short passage in the novel alludes to Walter Benjamin’s suicide at the Spanish border village of Portbou, her focus on Weiss/Weidel memorializes a literary tradition belonging to East European Jewry — the main target of the Nazi genocide.

In Mexico, Seghers was a prolific speaker and contributor to the anti-fascist journal Freies Deutschland. Here, her comrades included the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, the Cuban-born interior designer Clara Porset, and the Mexican muralists Xavier Guerrero, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Whereas in Paris she had relied on German exile presses and other small venues, 1942 brought a breakthrough — and much-needed financial support — when Boston’s Little, Brown and Company published The Seventh Cross in English. A Book-of-the-Month-Club best seller, it was made into a Hollywood film directed by Fred Zinnemann and starring Spencer Tracy, Hume Cronyn, Jessica Tandy, and Signe Hasso. It has since been translated into more than forty languages.

Disaster struck in June 1943 when Seghers was hit by a passing vehicle in Mexico City. She was hospitalized with a skull fracture, lay in a coma, and thereafter suffered from amnesia. During her recovery, she wrote her most famous and only autobiographical story, “The Excursion of the Dead Girls.” Written as if in a dream state, with multiple layers of place and time, the story tells of young Netty’s school excursion on the Rhine in 1912. Woven into its account are the subsequent lives and deaths of her schoolmates under Nazism. Shortly before she conceived her tale, Seghers learned that in March 1942, her mother, Hedwig Reiling, had been deported to the Piaski ghetto in Poland on a transport of 1,000 Hessian Jews. The story of the school excursion culminates in Netty’s inability to reach her mother who waits for her on the balcony of their house.

She published this in 1946, together with two other stories responding to the Holocaust. “Post to the Promised Land” memorializes members of a Jewish family who survived a Cossack pogrom in Poland in the 1890s and wind up in Paris, by way of Vienna and Kattowitz. Their subsequent lives, and deaths, cite the fates of Jewish migrants from Eastern Europe in the first half of the century. Meanwhile, “The End” depicts a former concentration camp guard’s desperate bid to avoid capture by the Americans. He has no regrets, except that the Nazi hierarchy he so eagerly served has abandoned him. This was a scrupulous, and for its time astoundingly accurate, exploration of the Nazi psyche; its protagonist embodied “the banality of evil” seventeen years before Hannah Arendt used this term in Eichmann in Jerusalem. These three tales stand as Seghers’s unequivocal statement on the Holocaust. Yet each has its own prose form, thematic focus, and narrative style — as if to say there is no single adequate or authentic way to write about the extermination of the Jews.

Postwar

Seghers returned to Germany after World War II as its preeminent and most internationally renowned anti-fascist writer. Anxious to write and be read in German, and to support the socialist rebuilding effort, she reached Berlin in April 1947 with the city still in ruins. Interviewed by the New York Times, she declined to say whether she thought “democratization” was possible in Germany — but commented that everyone she had met since arriving held “a political alibi in his outstretched hand.”

Her mother and other family members having perished in the Holocaust, Seghers did not find life among the Germans easy. In a letter to a friend, she called them “stunted” and “stultified,” and she described the survivors of the anti-fascist resistance as standing out from the crowd “like the first Christians from the spectators in a Roman arena.” As a communist, a Jew, and a woman, Seghers became a target of hostility in sectors of the West German press — a situation that intensified as the Cold War progressed. In 1950, she left the American sector and settled in East Berlin.

There, Seghers was respected and admired as Germany’s foremost socialist author. But she did not have an easy relationship with her Party. In June 1948, after visiting the USSR, she wrote to Lukács that she felt she had “entered the ice age.” In this time of fresh Soviet purges, the “anti-Titoism” campaign, the 1949 show trial against Hungarian Communist interior minister László Rajk, and the arrest and imprisonment of the American Quaker Noel Field in Budapest, Seghers’s loyalties were questioned. She was marked out as a “West-émigré” who had been in contact with Field and received aid from his refugee relief organizations during her escape from France. Similar “dubious” relations of hers were dredged up in preliminary interrogations for the 1952 show trials in Czechoslovakia.

Faced with such accusations, Seghers was pressured to relinquish her Mexican passport and assume East German (GDR) citizenship. As for her work, when Socialist Unity Party (SED) chairman Walter Ulbricht read her 1949 novel The Dead Stay Young — about the far right’s encroachment among the working class, from the murders of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht to the crimes of Nazism — he demanded to know why there was no explicit role for the Party. Indeed, Seghers’s writing was primarily concerned not with the Party, but with the people it claimed to represent.

Yet Seghers rarely tempered her outrage and opinions. Famous for her biting sarcasm and wit, at the 1950 Writers’ Congress she mounted a rousing defense of her 1932 novel The Wayfarers, inspired by the political avant-garde later denounced under Stalin. She also defended her radio play The Trial of Jeanne d’Arc at Rouen, 1431, written in the 1930s during the Stalinist purges. In 1952, she and her old friend Bertolt Brecht expanded the radio play for a Berliner Ensemble theater production — its first performance scheduled for the same week that the show trial of Rudolf Slánský and thirteen others was staged in Prague.

Notwithstanding these difficulties, Seghers did have supporters among Party leaders in Berlin and Moscow. As the GDR’s most prominent author, she was a feather in its cap — The Seventh Cross alone sold a million copies, in this country of just 17 million. In 1952, she was elected president of the East German Writers’ Union, a post she held for twenty-five years. This allowed her to influence developments in the arts — especially by defending the aspirations of young authors and artists — and act as a model for the GDR’s especially large number of women writers. Despite frequent unfavorable cultural policy turns, she managed to steer East German literature along a path that brought out the next generation’s best talents.

Asked by Western reporters why she remained in the GDR, Seghers often said it was where she could write about what was important to her and pass this along to others. Her cultural influence was enormous, with her books read by generations of workers, intellectuals, and schoolchildren. She was a writer’s writer: the plays of Heiner Müller and the prose of Christa Wolf are unimaginable without her example.

The Spirit of Her Time

Seghers’s postwar prominence in Europe as a woman writer and cultural figure was exceptional, matched only by Simone de Beauvoir in France. Photographs of her during Party meetings and World Peace Council congresses show her as the lone woman in a virtual sea of men. She traveled widely on behalf of both this council and the Writers’ Union, and in fall 1951, she was even able to revive her knowledge of Chinese, as part of a GDR delegation to the People’s Republic of China.

Yet despite her cosmopolitan self-identification, in the 1950s and 1960s, her writing focused primarily on socialism and everyday life in her adopted country, be it in stories about postwar land reform or, as in her two great GDR novels of 1959 and 1968, about the stabilization of industry previously in the hands of Nazi-affiliated capitalists.

The year 1956 brought the Hungarian Revolution — and the arrest of the leaders of the revolutionary government, including prime minister Imre Nagy and Seghers’s friend Lukács. Against this backdrop, she wrote the third of her Caribbean novellas, The Light on the Gallows. These three novellas, of which the first two appeared in 1949, deal with the Black Jacobin slave rebellions in Haiti, Guadeloupe, and Jamaica, suppressed by Napoleon’s troops. Seghers had them published together in 1962, just as anticolonial uprisings were spreading across the world. These were just a few of her many works depicting the struggles of indigenous people in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa, the last being Three Women from Haiti (1980).

A prolific author, Seghers produced eleven novels, more than sixty stories and novellas, and a similar number of essays. She did this despite major upheavals and circumstances in which her life was often threatened. She was also under police surveillance for most of her career, whether by the Gestapo, the FBI, the French Sûreté, or the Stasi. At the height of the Cold War, sales of her books in West Germany were boycotted; even when her collected works began to be published there in the 1960s, reviewers were largely hostile.

Yet in the latter part of that decade, Seghers’s books found a belated reception, both among the extra-parliamentary and student movements, and thanks to Willy Brandt’s Social-Democratic government’s recognition of the first generation of anti-fascists. From the late 1970s, Seghers’s works were integrated into West Germany’s school curricula — where they remain to this day.

Recent decades have seen resurgent interest in Seghers. The centenary of her birth in 2000 saw celebrations throughout Germany and the launch of a twenty-four-volume critical, annotated edition of her works, of which twelve volumes have appeared thus far. The numerous adaptations of her works include Hans Werner Henze’s Ninth Symphony, whose fourth choral movement, like Beethoven’s Ninth, sets to music a political and moral tribute to its time — in this instance, The Seventh Cross.

Major theaters in Germany have staged dramatizations of Seghers’s works, and many exist as films, most recently Christian Petzold’s widely applauded Transit, which carries the novel’s focus on wartime migration into the multiethnic present. New translations have appeared, including in English: Transit (2013); Crossing: A Love Story (2016); “The Excursion of the Dead Girls,” “Post to the Promised Land,” “The End,” and The Seventh Cross (2018).

Like Dante, Leo Tolstoy, and more recently Nadine Gordimer, Seghers was an epic writer who wrote against the grain of those in power. Her works evoke the spirit of her time in ways that most histories and documentaries cannot. Anyone who wants to know how people seeking justice can face adversity and still retain hope should read her books.