Patrice Lumumba on the Congo’s Independence: “Our Wounds Are Too Fresh and Too Painful”

Sixty years ago today, Patrice Lumumba marked the independence of the Congo with a blistering indictment of Belgian colonial rule. For the governments of Belgium and the United States, the speech made Lumumba a marked man: within a year, he was dead at the hands of their proxies.

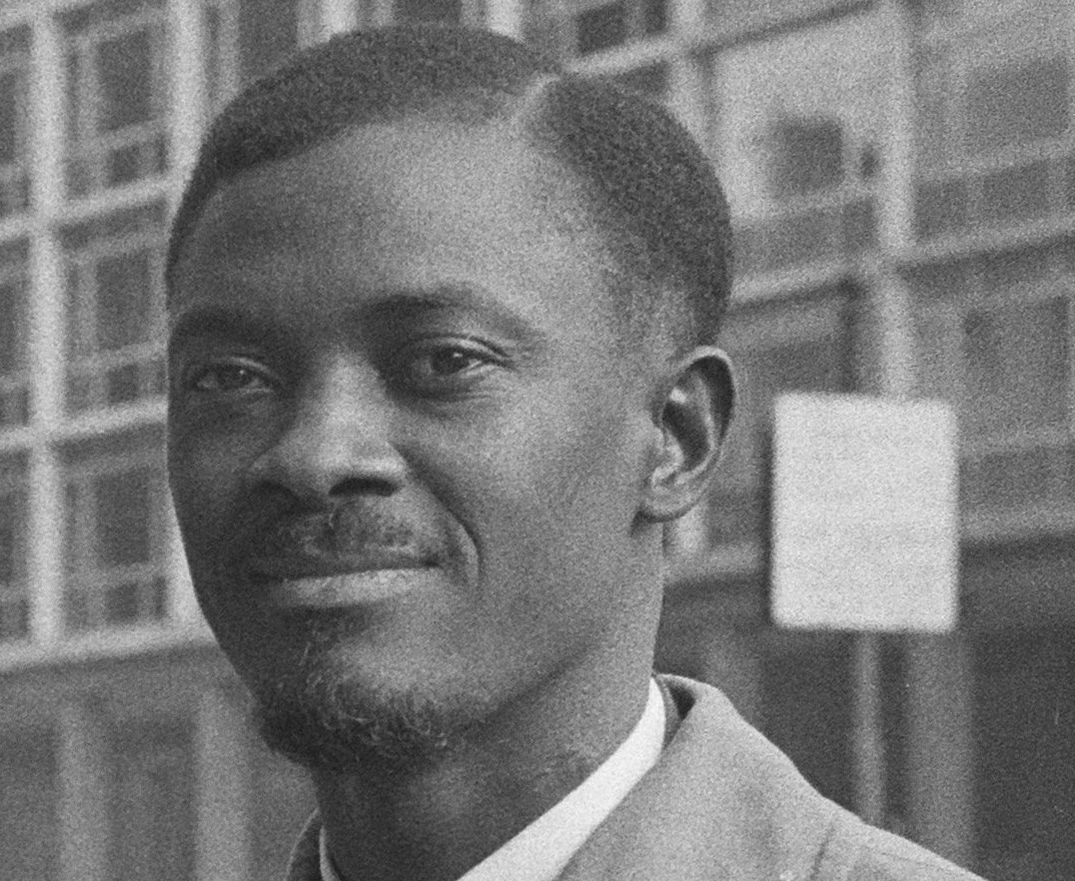

Patrice Lumumba was a leader of the Congolese independence movement and the first prime minister of the independent Republic of the Congo. (The National Archives of the Netherlands)

Sixty years ago today, the Congo won its independence from Belgian rule. The country’s first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, was planning to speak at a formal ceremony in Léopoldville (now Kinshasa). First, however, he had to listen to a speech by the Belgian king, Baudouin. Baudouin insisted on paying tribute to King Léopold II, who had carved out the Congo Free State as his personal fiefdom in the late nineteenth century.

As the Congolese people knew all too well, Léopold II was one of the greatest mass murderers of his time, responsible for millions of deaths in his hunger for colonial loot. Baudouin insulted the audience by sanitizing his predecessor’s image: “He appeared before you not as a conqueror but as a civilizer.” The Belgian monarch claimed that Congolese independence “marks the outcome of the work conceived by the genius of King Léopold II, which he undertook with tenacious courage and which Belgium has continued with perseverance.”

When Patrice Lumumba later took the stage, he delivered a blistering indictment of Belgian colonial rule, much to the indignation of Baudouin and the Belgian officials in attendance. The Congolese audience repeatedly interrupted Lumumba’s speech with rapturous applause; many others listened to it eagerly on the radio. But it cemented perceptions of Lumumba in Brussels, Washington, and other Western capitals as a dangerously independent figure at the helm of a major African state. A Guardian correspondent described the speech as “unpleasant” and “offensive.”

To undermine Lumumba’s fledgling administration, the United States and its allies sponsored a breakaway movement in mineral-rich Katanga and a military coup led by Mobutu Sese Seko, who went on to rule the country as a kleptocratic tyrant for three decades. Having been ousted as prime minster, Lumumba was murdered in January 1961 at the age of thirty-five. He remains an iconic figure of the anti-colonial struggle.

Men and women of the Congo, victorious independence fighters, I salute you in the name of the Congolese government.

I ask all of you, my friends, who fought tirelessly by our side, to make this June 30, 1960 into an illustrious day that will always be engraved in your hearts — a date whose meaning you will proudly explain to your children, so that they in turn might pass on to their grandchildren and great-grandchildren the glorious history of our struggle for freedom.

Although this independence for the Congo is being proclaimed today by agreement with Belgium, a friendly country with which we treat as equals, no Congolese will ever forget that it has been won in struggle — a passionate, idealistic struggle waged every day; a struggle in which we have not spared our strength, our sacrifice, our suffering, or our blood.

It was a struggle full of tears, fire, and blood. We are proud of it to the bottom of our hearts, because it was a just and noble struggle — an indispensable struggle to put an end to the humiliating bondage that had been forced upon us.

That was our fate for the eighty years of the colonial regime: our wounds are too fresh and too painful for us to banish them from our memory.

Taunts and Blows

We have known the backbreaking work demanded of us in return for wages that were not enough to satisfy our hunger, to clothe ourselves or house ourselves decently, or to raise our children as loved ones should be. We have known the jeers and taunts and blows that we had to suffer, morning, noon, and night, because we were “Negroes.” Who can forget that a black man was addressed as “tu” — and certainly not because he was a friend, but because the honor of “vous” was reserved exclusively for whites?

We have seen our lands confiscated, supposedly in the name of the law, which only ever recognized the right of the strongest. We knew that the law was never the same for whites and for blacks — for one set of people it was indulgent, for the other, it was cruel and inhuman. We have known the atrocious sufferings of those banished for their political convictions or religious beliefs: exiles in their own country, their lot was truly worse than death itself.

We knew that in the cities, there were splendid mansions for the whites and rickety huts for the blacks; that a black was not allowed into cinemas, restaurants, or “European” shops; that a black had to travel on the hull of a barge, while the white was in his luxury cabin.

And finally, who can forget the bullets that despatched so many of our brothers, or the dungeons into which those who would not submit to a regime of oppression and exploitation were mercilessly thrown?

“All That Is Finished”

We have suffered deeply from all of this, my brothers. But we, chosen by your elected representatives to lead our beloved country, we who have suffered in body and soul from colonial oppression — we tell you, from now on, all that is finished.

The Republic of the Congo has been proclaimed and our beloved land is now in the hands of its own children. Together, my brothers and sisters, we are going to begin a new struggle, a sublime struggle that will lead our country to peace, prosperity, and greatness.

Together, we are going to establish social justice and ensure that every person receives a just reward for their labor. We are going to show the world what the black man can do when he works in liberty, and we are going to make the Congo an example for all of Africa. We are going to ensure that the lands of our native country are used for the benefit of its children.

We are going to revise all the old laws and make new ones that will be just and noble. We are going to put an end to the persecution of free thought, and see to it that all citizens enjoy in full the basic liberties provided for by the [Universal] Declaration of Human Rights.

We are going to eliminate all forms of discrimination, whatever they may be, and ensure for everyone a station in life worthy of their human dignity, their labor, and their loyalty to the country. We are going to establish a peace, based not on rifles and bayonets, but on good hearts and good will.

A Decisive Step

And in all of this, my beloved compatriots, we can rely not only on our own great strengths and immense riches, but also on the assistance of many foreign countries, whose co-operation we shall accept as long as it is loyal and does not seek to impose any kind of policy on us.

In this field Belgium — which, finally heeding the lessons of history, has not tried to obstruct our independence — is prepared to give us its aid and friendship; to that end, an agreement has just been signed between our two equal and independent countries. I am sure that this cooperation will be profitable for both nations.

For our part, while remaining vigilant, we will respect commitments that have been entered into freely. And so, at home and abroad, the new Congo that my government is going to create will be a rich, free, and prosperous country.

But in order to achieve our goal without delay, I ask all of you, Congolese legislators and citizens, to assist me with all your strength. I ask you to forget about all of the tribal quarrels that exhaust us and threaten to make us despised abroad. I ask the minority in parliament to assist my government with a constructive opposition, and to remain strictly on legal and democratic paths. I ask you all not to shrink from any sacrifice to ensure the success of our grand enterprise.

Finally, I ask you to respect unconditionally the life and property of your fellow citizens and of the foreigners who have settled in our country. If the conduct of these foreigners is unsatisfactory, our justice will promptly expel them from the territory of the Republic; if, on the contrary, their conduct is good, they must be left in peace, because they, too, are working for the prosperity of our country.

The independence of the Congo is a decisive step towards the liberation of the entire African continent.

Sire, your excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, my dear compatriots, my brothers of the same race, my brothers of struggle, this is what I wanted to say to you in the government’s name, on this magnificent day of our independence, complete and sovereign.

Our government — strong, national, popular — will be the salvation of this country. I ask all Congolese citizens, men, women, and children, to set themselves resolutely to the task of creating a prosperous national economy that will ensure our economic independence.

Glory to the fighters for national liberation!

Long live independence and African unity!

Long live the independent and sovereign Congo!