The Life and Death of Lovett Fort-Whiteman, the Communist Party’s First African American Member

The first African American to join the Communist Party was born in Texas, and died as a prisoner in a Soviet gulag. This is the forgotten story of Lovett Fort-Whiteman.

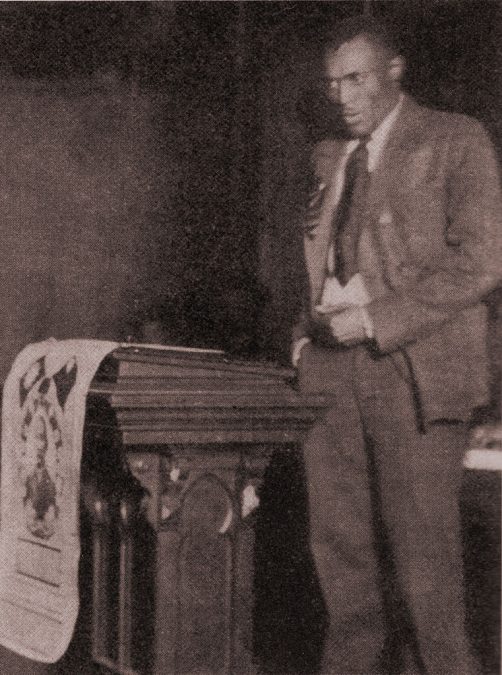

Lovett Fort-Whiteman speaking at the opening session of the founding convention of the American Negro Labor Congress in 1925. (Wikimedia Commons)

The first African American to join the Communist Party was born in Texas, and died as a prisoner in a Soviet gulag.

Lovett Huey Whiteman was the son of a freed slave from South Carolina, Moses Whiteman, and Elizabeth Fort, a Texas native. In early adulthood Lovett replaced his middle name with his mother’s maiden name, thereafter identifying himself as Lovett Fort-Whiteman.

Born in Dallas and educated in its segregated public schools, in 1905 Whiteman enrolled in Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, and upon graduation, spent a brief spell at Nashville’s Fisk University. His mother soon left Dallas, without Moses, and moved to New York City, wherewith the wages from a job at a steamship company, she paid Lovett’s college expenses and those of his younger sister, Hazel. By 1910 Elizabeth, Hazel, and Lovett had reunited in New York. Lovett aspired to become an actor, pianist, or showman, but Census records show him employed as a bellman.

In 1913 he ventured to the Yucatán Peninsula, where he worked as an accounting clerk in the hemp industry. Mexico was in the midst of its revolution and awash in radical ideas. While there, Fort-Whiteman picked up not only the Spanish language but the vernacular of the Left as well. When he returned to New York in 1917 he joined the Socialist Party of America (SP), starting a long career as a prominent radical. In 1926 Time magazine went so far as to label him as the “blackest of the Reds.” But much about his short life and tragic end remains a blank sheet, in part because he spent some fifteen years abroad, in places where records are either unavailable or unknown to American scholars.

Socialist Party

In New York, Whiteman won his way into the company of the SP’s leaders. Among them were A. Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; civil libertarian Elizabeth Gurley Flynn; Rose Pastor Stokes, a wealthy socialite and reformer; Robert Minor, a prominent newspaper cartoonist, born and raised in San Antonio; and Sen Katayama, a Japanese immigrant who would become a founder of Communist parties in the United States, Japan, and Mexico.

Fort-Whiteman was noteworthy because he represented a small but promising demographic in the Socialist Party: he was both black and American-born. A disproportionate number of the party’s ranks were drawn from white European immigrants, and most of its few black members came from the West Indies.

The SP had some eighty thousand members in 1917, organized into language federations that held meetings and published newspapers in their native tongues. Though black Socialists were formally members of the English-speaking section, by 1919 the most militant of them also belonged to the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB), a group founded and dominated by newcomers from the West Indies.

By that time, however, purges and splits had reduced the SP’s membership by half, a blow from which it never recovered. When the dust settled, two parties supportive of the Bolshevik Revolution had arisen, the Communist Party of America, whose members consisted mainly of immigrants, and the Communist Labor Party, composed mostly of native English speakers.

During this period, Fort-Whiteman for a while wrote columns as a drama critic for a socialist weekly and, like Randolph, agitated for admitting black workers into American Federation of Labor (AFL) unions. Ultimately, he decided to take his lectures on the road. In September 1919, when he appeared at three Ohio and three Pennsylvania cities, his approach was ecumenical. He addressed syndicalist, socialist, and communist audiences, and in one instance, a church congregation. He financed his lectures by taking collections at his venues, and on money that Hazel sometimes sent.

In Mexico, Fort-Whiteman had absorbed the outlook of the Casa del Obrero Mundial, a syndicalist group — one that believes in worker, not state, ownership of industry — like the American “Wobblies,” or Industrial Workers of the World. In Youngstown, Ohio, Wobblies introduced him to a pamphlet, “Justice for the Negro: How He Can Get It,” a tract that didn’t pull any punches. “Throughout this land of liberty, so-called, the Negro worker is treated as an inferior,” it declared. “He is underpaid in his work and overcharged in his rent; he is kick about, cursed and spat upon; in short, he is treated, not as a human being, but as an animal, a beast of burden for the ruling class.”

When a Youngstown IWW member offered Fort-Whiteman a Wobbly membership book, paid through January 1920, he accepted it, along with hundreds of copies of “Justice,” which he distributed at subsequent speaking engagements.

In late September Whiteman reached St. Louis, with plans to visit Hazel, who had married and returned to Dallas. He came into town with Robert Minor, who was slated to give a speech there. Minor was no stranger to the city’s newspaper readers: for six years before going to New York — where he had been the nation’s highest-paid cartoonist — he had plied his trade at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. His three-hour lecture on the Soviet Union drew an audience of 1,200.

Fort-Whiteman had no such luck with his debuts. An October 10 appearance at the Jewish Labor Lyceum, sponsored by the Communist Labor Party, drew an audience of a dozen. Everyone in the meeting hall was arrested. Though in the ensuing weeks, others were released, while Fort-Whiteman and an immigrant attendee were held for months on charges of sedition, later dismissed.

The raid on his appearance was supervised by the Radical Division of the Bureau of Investigation, headed by a twenty-four-year-old J. Edgar Hoover. Over the summer of 1919 — the so-called Red Summer of riots and strikes — the bureau had infiltrated radical groups from coast to coast. It singled out Fort-Whiteman for special investigation, sending its agents in Dallas to question his sister Hazel. Its report reveals that she was adept at dissembling, and that the bureau was obsessed with race: “Mrs. Harris is an educated and stylish negress,” it said, “the mistress of a rich and elegantly furnished home and mingles only with the aristocracy in darktown. . . . The sister swears that she never heard of her brother being mixed up in the race troubles . . . Speaking for herself she disclaims being a member of any organization or society or subscribing or reading any publications where social equality for the negro [sic] is advocated, preached or urged.”

Though the St. Louis office had a letter she had written to Lovett, the agents apparently took her denials at face value, perhaps because her husband stated that he forbid any mixing of his wife and “niggers who want to be on equal footing with the white folks.”

The American Negro Labor Congress

By 1924, the dueling Leninist parties had merged into one organization, the Communist Workers’ Party, later known as the Communist Party USA. Early that year Fort-Whiteman represented both the African Blood Brotherhood and the Communist Party at a Chicago congress of black organizations, the Negro Sanhedrin. He afterward resettled in Chicago as a Communist organizer and, that summer, appeared before the Comintern in Moscow.

In the audience among the delegates he addressed were Joseph Stalin, Ho Chi Minh, and Fort-Whiteman’s friend, Sen Katayama, by then living in Moscow as a member of the Comintern’s Executive Committee and head of its American Bureau. Fort-Whiteman also won the confidence of Nikolai Bukharin, a theoretician who had been a companion to Lenin during their years in prerevolutionary exile, and who, in 1924, was a member of the Soviet Politburo.

At the end of the Comintern meeting, Fort-Whiteman stayed in Moscow as a student at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East. He toured the USSR, was made an honorary member of a Ukrainian Cossack division, and, during a visit to Turkestan, supposedly rechristened itself as Whitemansky.

While in the Soviet Union, Fort-Whiteman was also lobbying the Comintern on behalf of an idea. He proposed that the Communist Party create a group called the American Negro Labor Congress (ANLC), whose job would be to build union membership among blacks, to protest lynching and other outrages, and to challenge Jim Crow everywhere. In February 1925, the Comintern’s Executive Committee accepted the idea and named Fort-Whiteman as its organizer. He returned to Chicago that month and for the next three years promoted the ANLC in lectures wherever he could, even at the Harvard Liberal Society.

The West Indian immigrants who had preceded him as Communists did not approve of his elevation. The ANLC was supposed to become a mass organization, one that included members whose only agreement with the Communist Party was with its racial program. But Fort-Whiteman, his detractors said, tied it too much to the party and the Soviets.

That tendency showed at the ANLC’s founding convention in October 1925. Fort-Whiteman took charge of the entertainment for its opening night. He chose an ostensibly Russian ballet troupe and a Russian drama. The comrade who became known as Harry Haywood recalled it in these words:

The meeting took place in a hall on Indiana Avenue . . . in the midst of the Black ghetto. When I arrived it was packed —perhaps 500 people or so. Inside I was suddenly attracted by a commotion at the door. . . . I walked over to see what was the matter. Something was amiss with the “Russian ballet” which was about to enter the hall. A young blonde woman in the “ballet” had been shocked by the complexion of most of the audience, which she had apparently expected to be of a different hue. Loudly, in a broad Texas accent, she exclaimed. “Ah’m not goin’ ta dance for these niggahs!”

Somebody shouted, “Throw the cracker bitches out!” and the “Russian” dance group hurriedly left the hall.

The Russian actors remained to perform a one-act Pushkin play. They, at least were genuine Russians . . . But alas, it was in Russian. . . . Its relevance to a Black workers’ congress was, to say the least, unclear.

Though Robert Minor declared that the meeting gave the ANLC “a splendid foundation,” only a few dozen attendees, most of them Chicagoans, returned the next day.

It did not help that Fort-Whiteman wholeheartedly mimicked the Russians even in his mode of dress. As Haywood described him:

Fort-Whiteman was a truly fantastic figure. . . . He had affected a Russian style of dress, sporting a robochka (a man’s long belted shirt) which came almost to his knees, ornamental belt, high boots and a fur hat. Here was a veritable Black Cossack who could be seen sauntering along the streets of Southside Chicago. . . . There was no doubt that he was a showman; he always seemed to be acting out a part he had chosen for himself.

Other Communist activists found Fort-Whiteman remiss as an organizer. They were especially irritated that the ANLC’s organ, The Negro Champion, was unable to publish regularly. (Sadly, the issues Fort-Whiteman edited have not survived.) Though they complained to Minor, then the head of the party’s commission for “Negro Work,” he ignored them.

Ohio district organizer Israel Amter, a white man who, like Minor, was in the forefront of the intraparty crusade for multiracial organizing, reported to general secretary Charles Ruthenberg that on a recent visit “. . . Comrade Whiteman did not carry out the instructions of the Polcom, to the effect that after each meeting . . . he is to organize the workers into the branches of the ANLC. . . . He makes a speech and then disappears.

But Ruthenberg was apologetic in his reply a few days later. “No doubt you have just cause to complain in regard to the way Whiteman handled the Negro meetings,” he wrote. “There are similar complaints . . . in regard to failure to make the meeting as scheduled. However, at the present time Whiteman represents the best material we have for our Negro work, and we must be as patient as possible, and endeavor to develop more responsibility in organizational work on his part.”

A Crisis in Moscow

While the ANLC under Fort-Whiteman’s leadership was stumbling along, a crisis was maturing in Moscow. When Lenin died in 1924, a power struggle began in the Politburo over who should take his place. Slowly Joseph Stalin gained the upper hand and showed his strength in 1926 by engineering the removal of Leon Trotsky, Lenin’s choice as successor. Fort-Whiteman was not endangered by the move because he was a follower of Nikolai Bukharin, who had supported Trotsky’s ouster.

But by 1928, Stalin was arguing inside the Politburo that capitalism was headed into tumult and decline. Reformists, he charged, would try to save it with reforms. In his mind, that made them enemies, not allies. Stalin called such groups “social fascists.” These included the AFL, the NAACP, and the Socialist Party.

Bukharin didn’t agree. He had already questioned Stalin’s plan for a crash industrialization in the USSR, and at the 1928 Comintern session, he argued that capitalism was not on the verge of collapse. Ruthenberg had by this time died, and Jay Lovestone, just thirty years old, a former leader of Socialists at the City College of New York, had taken his place. Alongside Bukharin, he argued that reform groups were not to be considered enemies to the Communist cause.

Lovestone brought Fort-Whiteman into play during deliberations about racism in the United States. Everyone agreed that due to their circumstances, American blacks could be reached by radical appeals. But they differed about when that would happen and how to facilitate the change.

Most American blacks still worked in agriculture and lived in the South, where, as sharecroppers and tenant farmers, they formed a class similar to the European peasantry. Basing themselves on Marx’s writings about the French Revolution and Paris Commune, most Marxists regarded peasants with suspicion, as a conservative, even reactionary, class.

During the 1928 Comintern debates, Lovestone maintained that capitalism in the United States would continue to develop, and that blacks would continue to flee the farms for industrial jobs in the South, as well as the North. He foresaw no need to organize sharecroppers and tenant farmers because, he said, the American peasantry was being phased out. Fort-Whiteman buttressed Lovestone’s position by preparing an address arguing that even organizations like the ANLC were not really necessary.

Russian Cominternists took a dim view of Lovestone’s “American exceptionalist” line, however. Years prior, Lenin was said to have remarked that the circumstances of African Americans looked to him like those of an “oppressed national minority.” This meant that American blacks had a right to “national self-determination,” a status that the Bolsheviks claimed. Their “nationalist” program found favor with Sen Katayama and the ABB members who had migrated to the Communist cause. It noted that in some two hundred counties from East Texas to Virginia, blacks constituted the majority population, yet were effectively barred from voting. The area that was called the Southern Black Belt, they said, could potentially become a republic of the Soviet-style.

The Comintern defused this dispute by adopting both the integrationist and nationalist proposals. It ordered the American Communists to organize the South, to agitate for both the right of self-determination and for the unionization of industry on a racially integrated basis. But the Comintern did not compromise about the coming collapse of capitalism. Bukharin and Lovestone’s theses were roundly defeated.

Fort-Whiteman remained in Moscow when the conference ended. But as might have been expected, in 1929 Bukharin was purged from the Soviet Politburo and Lovestone was expelled from the American Party.

Yet even with his allies in disarray, Fort-Whiteman found a job as a teacher at a school for English-speaking students, most of them the children of technicians who had been contracted to assist Stalin’s industrialization push. An American journalist who visited the school in 1932 reported that Whiteman claimed to be a graduate of the University of Chicago and “speaks English in a beautifully modulated Oxford drawl.” Perhaps he was acting again.

He soon tried his hand at scriptwriting. In June 1932 the cast of a proposed movie about black life in Birmingham, Alabama arrived by boat to Leningrad. Among its twenty-two members was the poet Langston Hughes. Fort-Whiteman hired a brass band to greet them with “The International” as they disembarked, then escorted the crew to Moscow, where its members stayed in high style as state guests. But the film, tentatively named “Black and White,” was never made. Its chief writer, a Russian whom Fort-Whiteman assisted, hadn’t the faintest idea of what black life in the United States was about, and Politburo members opposed the project because they feared it would complicate the USSR’s diplomatic relations. After more than two months of wrangling, the would-be actors went home.

Rearrest and Death

Fort-Whiteman, ever the polymath, soon landed a two-year fellowship in ethnology at Moscow University and somehow parlayed that into a job as a researcher on fish breeding. But in 1933, he requested permission from the American party to return to its ranks. His letter was snagged by Soviet authorities, who rather than forwarding it, entered it into police records.

In his off-hours, expat Fort-Whiteman often dined with visiting American blacks, especially party members. In early 1936, following a hot dispute with American comrades, he was banished to Alma-Ata, a city in Kazakhstan that had been Trotsky’s first stop on his way to exile. There Fort-Whiteman became a schoolteacher again. But the Soviet police did not forget about him. In early 1937 Bukharin was arrested, given a show trial and convicted of conspiring to overthrow the Soviet state. A year later he was shot. Within two months of his execution, Fort-Whiteman was rearrested and sentenced to five years of hard labor at a gulag in the gold-mining fields of Siberia.

According to a fellow inmate, he was frequently unable to meet work quotas and was punished with beatings. Either from those or from unknown causes, he lost his teeth. On January 13, 1939, at the age of forty-nine, he died in the gulag, his death certificate said, of “heart failure.” Had an admirer penned the certificate, it might have plainly said that he died of a broken heart.