J. Posadas, the Trotskyist Who Believed in Intergalactic Communism

From his hopes in human-dolphin socializing to his claims that UFOs were sent by alien communists, J. Posadas’s quixotic beliefs are today legendarized in countless memes. But a new biography suggests that the Argentinian Trotskyist was not such an outlier — and explains why his revolutionary optimism draws such ironic veneration today.

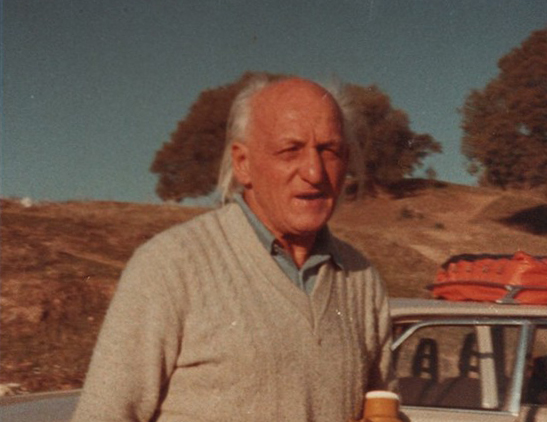

J. Posadas.

- Interview by

- David Broder

Posadas (1912–1981) is one of the most famous — and ridiculed — of Trotskyists, notorious both for the cults he named after himself and his claim that UFOs were evidence of communist societies in other galaxies. Together with his belief that nuclear war might hasten the advent of communism (and his hopes that dolphins could be integrated into the new society), Posadas’s xenophilia has in recent years fed his legendarization by countless meme pages, or even outright LARPing in the form of the Posadist Caucus in the Democratic Socialists of America.

For A.M. Gittlitz, author of a new book on J. Posadas, this ironic veneration of the Argentinian Trotskyist also has something to say about our political moment. In times in which it’s hard to believe in the future, Posadas’s wild optimism appears as a caricature of an earnestness and sheer sense of belief now almost lost to us. In his richly researched I Want to Believe: Posadism, UFOs and Apocalypse Communism, Gittlitz documents the more serious side of Posadas’s activism in postwar Latin American Trotskyism, while suggesting that even his strangest claims were not so detached from the UFOlogy of the time.

David Broder is the translator of J. Posadas’s Flying saucers, the process of matter and energy, science, the revolutionary and working-class struggle and the socialist future of mankind. He spoke to Gittlitz about Posadas’s interest in the extraterrestrial, his comrades’ involvement in the Cuban Revolution, and how he became an online legend.

First, let’s talk about Posadas the man. Some of the comments cited in the book — notably, his prediction that jokes would be “unnecessary” under communism — cast him as an intensely ascetic figure, yet this also seems linked to his projection of militant commitment and seriousness. What kind of formative experiences took Posadas toward his vision of organization and “revolutionary morality”?

His asceticism came from a certain interpretation of Lenin and Leon Trotsky’s conception of a disciplined vanguard party, widespread in the Latin American Bureau of the Fourth International. But a lot of the more cultish aspects and bizarre utopian visions came from his own idiosyncrasies.

Posadas, born Homero Cristalli, grew up in intense poverty with (at least) nine siblings in working-class Buenos Aires in the 1910s and 1920s. After the premature death of their mother, they had to beg neighbors for eggs, work odd jobs for pennies, and sometimes subsisted on green bananas for days on end. The malnutrition left him with both permanent health problems and a belief that we need to consume much less than what is normal under capitalism.

In his twenties, his tireless work distributing newspapers for the Socialist Youth drew the attention of Buenos Aires’s small proto-Trotskyist milieu, and he was recruited as a union organizer. Although he was not an intellectual, his diligent attention to the tasks assigned to him made him a valuable asset among the fractured field of anti-Stalinist communists. It was only in the 1950s, when he had risen to the position of Secretary of the Latin American Bureau (BLA), when some in the movement reported Posadas was manic. He demanded that his militants conform to his own lifestyle of lite sleep and the endless production, translation, and distribution of texts.

When he was denied leadership of the Fourth International in 1961, and the BLA broke into its own International, he made “revolutionary morality” central to the movement. Non-procreative sex, especially between militants who weren’t married, was prohibited. Posadas hoped sexual desire would fade away under communism, and perhaps technology would replace sex altogether. This, too, reflects Posadas’s own sexless marriage.

By the early 1970s, Posadas’s harsh authoritarian “monolithism,” his increasingly strange texts, and the major repression of his movement in Latin America led most of the youth and working-class base to leave the International. Then came the expulsions of the remaining intellectual core of the movement — serious Marxists like Guillermo Almeyra and Adolfo Gilly. The only ones left were young militants who entered socialism through the texts of Posadas alone and had barely even read Marx or Trotsky.

He believed his movement’s small size and inexperience was a virtue — for these militants could be perfectly harmonized as transmitters of his ideas to the leaders of the workers’ states that would, he thought, build communist society after the expected World War III. The communal living, submission to a charismatic leader, doomsday predictions, abusive self-criticism sessions, escalating spirals of commitment, separation of militants from their partners and families, and taking young militants as sex partners, make it fair to qualify Posadism as a cult. But compared to dozens of other postwar Leninist organizations of various sizes, these features were by no means unique.

Posadas played an important role in Latin American Trotskyism and particularly in the period of the Cuban Revolution. Yet his followers entered into open conflict with Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. Can you tell us about the role they played, the place the guerrilla struggle had in Posadas’s thinking, and why that relationship fell apart?

Trotskyists internationally were skeptical of Castro’s revolution throughout the 1950s, but the small circle of Cuban Trotskyists were enthusiastic supporters. Some fought in the sierras of Guantanamo, and one was a close comrade of Castro, sailing with him on the Granma in 1956. After the revolution, they quickly formed the Partido Obrero Revolucionario (Trotskista) (POR(T)) under Posadas’s BLA, and were allowed to use state radio to organize their first congress. They began to organize a strong network throughout the Cuban working class, pushing for the formation of Soviets, the nationalization of industry, and expulsion of the Guantanamo military base.

The Soviet-aligned Partido Socialista Popular (PSP) quickly identified the POR(T) as a threat to the revolution. The USSR hoped that Cuba would follow its policy of “peaceful coexistence” with the United States. But on many issues Castro and Guevara tended closer to the POR(T)’s own radicalism, defying the United States by nationalizing dozens of industries and utilities in 1960.

Early attempts to suppress the Trotskyists by PSP agents were thwarted by Guevara. But after the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 and the missile crisis of 1962, the POR(T) continued pushing bellicose rhetoric, against the Soviet Union’s policy of détente. Castro thus gave the PSP a free hand to clamp down on the Trotskyists until nearly every member was arrested.

Even then, the Posadists internationally supported Castro — but above all, they supported Guevara. Adolfo Gilly wrote in the Monthly Review that Guevara’s policies as minister of industry were properly anticapitalist, relying on a disciplined workforce motivated by revolutionary enthusiasm instead of the capitalistic “workers’ self-management” initiatives pushed by the PSP-run Ministry of Agriculture. When it came to confrontation, the Posadists were impressed that Guevara often stated that nuclear war might be a necessary evil to defeat imperialism — and saw his conception of the foco guerrilla cell as a third-world variant of the Soviet workers’ council. Posadas experimented with this idea in Guatemala, where he became the ideological figurehead of the MR-13 rebels, pushing them to form armed revolutionary peasant councils wherever they went.

When Guevara resigned from the government and disappeared, the Posadists wrote that Castro, under pressure from the Soviets, had killed him. This, along with the guerrilla war in Guatemala devolving into a genocidal counterinsurgency, infuriated Castro enough that he denounced Posadas and Trotskyism in general at the 1966 Tricontinental Congress. When Guevara was finally killed by the Bolivian army the following year, Posadas called the photo of his corpse a forgery.

Posadas is probably most famous for his comments on UFOs as harbingers of a more developed — and thus postcapitalist — society. You quote his son Léon Cristalli playing down this focus, remarking “When Carl Sagan says it it’s fine, but when Posadas said it … he was a planetary madman.” The interesting thing here is the suggestion that what Posadas wrote about was drawn from a wider cultural phenomenon, the UFOlogy of the 1950s–60s and also Bolshevik cosmism. What precisely was new about Posadas’s intervention on this theme?

Cristalli is correct to defend this aspect of his father’s work in this way. Sagan was a pioneer of the astrobiological, and, in my opinion, political science of the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). Along with Soviet astrophysicist Iosif Shklovsky, Sagan represented the most optimistic pole within SETI, initiating projects like the Allen Telescope Array and the Voyager Gold Record on premises very similar to the main logic behind Posadas’s UFO essay. That is, if contemporaneous communicable alien civilizations do exist, they will have had to sustain themselves for thousands of millennia. They must, then, have overcome or avoided entirely our own imperialist and self-destructive impulses — and so if we have the ability to contact them, we should do so without fear. Shklovsky even wrote that it was Marxism that would deliver humanity to this higher-level longevity. Sagan kept his leftist sympathies close to his chest, but he didn’t exactly disagree.

But Posadas’s 1968 essay on UFOs was not so much a matter of committing his movement to UFOlogy, or restoring the cosmist tradition to communism, as of settling an internal debate within the movement’s intellectual core over the reality and significance of UFOs. Yes, the phenomenon is real, he said, and if we can contact them, we should. But he added that his comrades shouldn’t focus too much on trying to do that or speculating what UFOs are doing here or what their society is like — for we have everything we need to create a sustainable utopia on Earth right now. He remained a believer, but never publicly wrote on the subject again.

A key figure here is Dante Minazzoli. Can you tell us about his interest in UFOlogy and what his comrades thought of this? Was there a certain point at which Posadism became mainly “famous” among other Trotskyist groups precisely because of this focus?

Dante Minazzoli and Homero Cristalli founded the Grupo Cuarta Internacional (GCI) in the mid-1940s as a small circle of proletarian militants committed to Trotsky’s vision of establishing the Fourth International as a world revolutionary vanguard. At that point, Posadas was just a collective pen name, and since Cristalli was not much of a writer, Minazzoli likely wrote a lot of what was published under the name J. Posadas. In some ways, Minazzoli was as much Posadas as Posadas himself; although it was a speech by Posadas that became the famous UFO essay, its content was based on Minazzoli’s long-held extraterrestrial hypotheses.

In 1947, after Kenneth Arnold’s story of flying saucers and news of the Roswell incident spread through tabloids worldwide, there was a flap of UFO sightings around Argentina. Influenced at a young age by science fiction and the cosmist literature of Camille Flammarion, Minazzoli believed humans are just one species among many in the universe, and our destiny is to meet and fraternize with them. He urged his comrades in the GCI to analyze the phenomenon, but they prohibited him from talking about it.

Two decades later, when the Posadist International’s leadership believed themselves to be the legitimate successors to Trotsky and Lenin, and thus the intellectual vanguard of world revolution, Minazzoli brought up his thesis again in the context of a reading group on Friedrich Engels’s Anti-Dühring and Lenin’s Materialism and Empirio-Criticism. He made a dialectical materialist argument for the existence of extraterrestrial life, and a political argument that the UFOs were here to observe us as we achieved socialism so we could be welcomed into the galactic community. He was probably not alone in this belief, but other International leaders, like Guillermo Almeyra, urged him to cut it out.

But Minazzoli’s insistence on the topic moved Posadas to comment. The transcribed speech was published in a few of the Posadist newspapers worldwide. Militants from other Trotskyist groups already read the Posadist press for its bizarre conspiracy theories, predictions, and screeds on revolutionary morality. The UFO essay became a cult classic among them. Rumors of it spread through the fractured Trotskyist movement as evidence that their rivals were truly mad — and that they had chosen sects correctly.

You tell us that Posadas returned to attention — or perhaps, neo-Posadism emerged in an unprecedented way — in the 2010s thanks to meme pages like the Intergalactic Workers’ League — Posadist, focusing on both his catastrophist hopes in nuclear war and his “unreal” vision of a new society where man would commune with dolphin. In your account, this isn’t just because Posadas is funny, but because ironic veneration of his extreme revolutionary optimism somehow fits the mood of our time. Could you explain this a bit more?

Although a handful of Posadists continued, and still continue, their militancy, the movement largely faded from even its small relevance within Trotskyism after Posadas’s death in 1981. But the UFO essay and his enthusiasm for nuclear war remained legendary among Trotskyists and “train-spotters” of small revolutionary left sects. Among these was Matthew Salusbury, an intern for a magazine of the paranormal, the Fortean Times. He pitched an article that the British Posadists of the Revolutionary Workers’ Party were a “Trotskyist UFO cult.”

Although it hyperbolically leaned into the UFO angle, and unearthed, for the first time, Posadas’s late-life obsession with dolphins, it became the main referent for Posadas’s Wikipedia page, piquing many imaginative discussions on leftist message boards. In 2012, you translated the UFO essay into English for Marxists.org, which showed his interest in aliens was more than just a legend. Then, in 2016, as the insanity of the US and UK elections radicalized bizarre corners of the internet, Aaron Bastani’s concept of Fully Automated Luxury Communism took off as a leftist meme.

Space was added to the schema, and a cartoonish Posadas alongside mushroom clouds, whizzing flying saucers, and dolphins leaping into space naturally followed. The Intergalactic Workers’ League – Posadist was probably the most successful spin-off meme page. To date, it’s produced hundreds of memes, earned tens of thousands of followers, and its administrators occasionally venture out to a May Day parade or leftist event in character.

As a result of the memes, Posadas has become (in the Anglosphere, at least) one of the most notorious names in the pantheon in the history of revolutionary socialism — outpacing his rivals and, at times, even overtaking Trotsky himself in terms of Google searches. Some have criticized the enthusiasm as cruel, citing a false rumor that Posadas was driven mad through torture, or that the Posadas memes do not take seriously the history of a movement that made heroic contributions to the South American labor movement and saw dozens of its militants killed and tortured.

It’s a fair point, and that’s part of why the bulk of my book offers a sober history of the Posadist International’s origins and politics. But I also see a side of that is more positive. Young leftists today find themselves in between a century of counterrevolution and a future that seems destined to continue slowly sinking into dystopia. Posadas, who came to prominence in the 1950s as the spread of colonial revolution made it common for revolutionaries to believe a nuclear third world war was imminent, was the most extreme “catastrophist” thinker — believing the war was both necessary and desirable, and that utopia was on the other side.

So, one way to read the Posadist memes, in absence of a potential world war between communism and capitalism, is that “we’re fucked, drop the nukes, get it over with already.” But there’s also openness to another possibility —that something strange and unexpected could happen, the emergence of a new Lenin, a mass, religious-like awakening of the working class, or a disaster that devastates the dominant order leaving the working class to rebuild the world on our own terms. Essentially, anyone who believes communist revolution is possible thinks something like this, even though to most people that’s as ridiculous as waiting for the aliens.

It also seems that the veneration of Posadism has coincided with the collapse of other self-styled revolutionary organizations in recent years — indeed, in Britain this was also expressed by meme pages like Proletarian Democracy, which called for a “Seventh International” and asked readers to crowdfund a “workers’ bomb.” Is mocking Posadas a way of dealing with our disappointment in Leninism? Or just an easy scapegoat?

For decades, Posadas was like a funhouse mirror at which sectarian leftists would laugh at their own distorted image. The humor around Posadas today is totally different. The people who are into the memes (a few ex-Trots among them, but by and large the demographic is young people who have never engaged in militancy) aren’t mocking a strange sect of Trotskyism, or Trotskyism in general, or Leninism in general, but the entirety of the failed revolutionary socialist tradition.

Ironically though, it’s not a critical mocking. It’s more ironic and absurd. I think at the bottom of it is a curiosity about those who once believed in anything so strongly that they would fight and die for it. There’s a respect for it. It comes from a place of wanting to be a part of something like that, but not really being able to believe in it.

As well as exploring Posadism’s stranger ideas, this is a richly textured biography of the man himself. Can you tell us a bit about why you wanted to write this book — and how you went about piecing the story together?

I wanted to write a science fiction story, something like a communist Illuminatus! Trilogy, with Posadism as a main part. But as I researched, I became far more interested in the actual history — little of which has been written about in English.

I visited the major archives of the movement’s internal documents in Amsterdam and London, and found additional materials in Paris, Stanford University, Mexico City, Montevideo, and Argentina. While in Buenos Aires I knocked on the door of León Cristalli, now secretary of the small International, but he refused to talk to me. Later I heard he bragged about rebuffing an imperialist agent from the New York Times. The secretary of the Uruguayan section was also reluctant to talk to me, but was so friendly he couldn’t help himself, and we ended up chatting off the record for a couple hours. I was also fortunate to meet an original Cuban Posadist at the Trotsky conference last May in Havana. Although most veteran Trotskyists I met described Posadas with little more than nasty jokes, they all had a lot of respect for the original militants of the BLA.

Through Sebastian Budgen I talked to an ex-militant of the Italian section, Luciano Dondero, who alluded to particularly intriguing untold parts of the story, like the sex scandal that served as a pretext to the expulsion of the intellectual core, and the daughter that Posadas had late in life, groomed to be his messianic heir. Other personal details of Posadas’s life, from his earliest memory witnessing the near-revolutionary Semana Trágica of 1919 unfold from his window in Buenos Aires, to his direct support for guerrilla insurrections in Algeria, Cuba, and Guatemala, his failure to recognize the importance of the ’68 uprisings, the movement’s repression in the Operation Condor dictatorships, and the sad demise as a marginal authoritarian cult, served as a poignant story — an example corresponding to the arc of revolutionary socialism’s failure in the twentieth century.

At the same time, I became fascinated with Trotskyism — which I had never really taken seriously before. Their conception of militancy was far different from what I was used to growing up in the anti-authoritarian anti-globalization milieu. I found that commitment to program a really admirable tradition my generation lacks. It also seems obvious that the dozens of global uprisings we’ve seen in the past years would be stronger with some level of international coordination, and a guiding conception of what it means to be anticapitalist, how the working class can take power, and what to do afterward.

This is not to say a resurgent Fourth International or FORA (the anarcho-communist union of which the parents of Posadas and Minazzoli were part), or any new attempt at an old model, would work. But it is important to understand what they were trying to achieve, why they were established, and why they failed. In the 18th Brumaire, Marx wrote about how revolutionaries who find themselves in hopeless situations look to conjure figures from the past in hopes of coming up with new ways to move forward. It is ironic enough to resurrect Lenin, Stalin, or Mao for this purpose, and Trotskyism always had this strange tone of self-defeatism. With Posadas, at least, there is no mistaking the irony inherent in the necessary task of creating something radically new from the ruins of history.