Wall Street Is High on Government Supply

For more than a decade, the US government has been taking over ever larger portions of the financial system to prop up shaky markets. It hasn’t worked. We need a real socialization of finance — for the majority, not the banks.

Traders work on the floor during the opening bell on the New York Stock Exchange on March 9, 2020 in New York. Timothy A. Clary / AFP via Getty

In the last week of February, the stock market saw its fourth most severe decline in modern history. On February 27 the Dow Jones Industrial Average and S&P 500 both suffered their fastest ever “corrections” (defined as a drop of 10 percent or more). The Dow dropped 12 percent. The S&P fell 11 percent. On Tuesday, March 3, the Federal Reserve intervened with an emergency rate cut of fifty basis points or half a percentage point — the first unplanned rate cut since the height of the 2008 crisis. But the emergency response did little to stop the downward slide of financial markets.

All this despite the fact that by conventional metrics the economy has been in good shape as of late: the lowest unemployment rates since the late 1960s, low inflation, and even some moderate wage growth.

The sell-off was triggered by the coronavirus, or rather the economic impact of efforts to contain it. But the outbreak was only the trip wire. The deeper causes of this crisis are decades of neoliberal austerity, asset stripping, and underinvestment in the real economy coupled with massive flows of cheap money from the Federal Reserve to the financial sector.

In fact, since the crash of 2008, Wall Street has become structurally dependent on socialized government finance. With one hand Wall Street borrows from the Federal Reserve at effectively zero percent interest, then with the other hand Wall Street loans that money back to the government (buying treasury bonds) at about 1 percent. This so-called “carry trade” started like many addictions, as a form of emergency medicine. Now markets, like junkies without a fix, are sick and the only way they can get right is another injection of government cash.

Several stark if often missed lessons emerge from this moment: 1) American finance has already been largely de facto socialized; 2) federal monetary policy is always already political; and 3) the jig is up, or nearly up, on the American version of Junkie Capitalism, or what Yanis Varoufakis in the Greek context called “extend and pretend” that is the practice of addressing each financial crisis by re-inflating asset values with government credit.

With the Federal Reserve’s main interest rates at close to zero, another conclusion is also clear: policy makers are trapped. If the current downturn snowballs into a full-blown financial panic and then into a wider economic crisis, only egalitarian economic redistribution aimed at working people and the real economy will drag capitalism from the slump. The old tricks of deregulation, regressive tax cuts, and shots of public credit have worn out. The real economy needs help in the form of popular debt forgiveness, green public works, free higher education, and significant socialization of health care.

How We Got Here

In response to the crash of 2008, which was triggered by the overproduction of subprime mortgage-backed securities, the US government had to rescue the banks because they were, and still are, genuinely “too big to fail.” Collapse of one or two of these financial giants would trigger a global economic meltdown.

In response the federal government did three things — all of which inadvertently set up the current crisis. First, the Federal Reserve cut its benchmark federal funds rate from 5.25 percent going into the crash to a historic low of 0.25 percent by December 2008. The fed funds rate is the rate at which banks charge each other for overnight loans at the end of every business day and thus reverberates out to shape interest rates in general. This cheap credit from the Fed helped to inflate stock prices but did little for ordinary people.

Second, the US Treasury Department bought (nationalized) portions of the country’s nine largest banks via the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP); but the government did not use its ownership stake to shape a progressive investment agenda in things like clean energy, nor did it do much to assist distressed homeowners. TARP did however help boost asset prices.

Third, the Federal Reserve — through its Quantitative Easing (QE) programs — went directly into the markets and bought nearly $2 trillion worth of financial assets from private banks and brokerage houses. This, like the other emergency actions, artificially boosted asset prices but did nothing to relieve the 9.3 million American homeowners who faced foreclosure, nor anything for the 44.7 million Americans yoked with student loan debt, nor the over 130 million Americans who report financial hardship every year due to medical expenses.

In combination, the three moves made by the Fed and Treasury amounted to a creeping, de facto nationalization of finance in which publicly controlled institutions artificially increased demand for the assets of private banks by pumping money into the financial sector. In homage to the tortured nomenclature of the Cold War, let’s call this “actually existing” socialized finance.

Tapering Off the Meds … Almost

The federal government did all this hoping to revive the financial sector and then gently wean it off credit infusions. Indeed, that began to happen.

In December 2014, the Treasury sold its last TARP-acquired formerly toxic asset. And — as if to didactically drive home the old adage, “buy low sell high” — TARP actually turned a profit. The program invested $426.4 billion at the bottom of the market. Then as asset values recovered it sold at higher prices, ending with a net gain of $15.3 billion.

Late 2014 also saw the Fed end the purchasing portion of its third and final QE buying binge. The Fed did not then start selling the vast piles of assets it had accumulated but rather just held them. (European and Japanese QE efforts went on until as recently as 2016.)

Even the Federal Reserve benchmark federal funds rate started inching back up. In 2016, it edged up a hair. Then in 2017 it crept to a target rate of 1.50 percent. And by December 2018 the target rate had reached 2.25 percent. A higher federal funds rate — or rather the ability to drastically lower it — is an essential tool for fighting any future crash.

Over the last two years it appeared as if the financial medicine had worked — at least in its own narrow, economically unfair, terms. Faith in the financial system was restored, the housing market was resuscitated, employment was picking up. And all without the widespread inflation so feared by most orthodox economists and media pundits.

But alas, trouble soon returned.

Repo and the Return of Crisis

On September 17, 2019, as if sucker punched, a rather humdrum, yet huge and vitally important, section of finance — the $1 trillion a day US repo market, the backbone of overnight interbank lending — suddenly failed to clear. Government financial firefighters rushed to the scene and hosed down the blaze with hundreds of billions more in liquidity.

And, boom, before anyone realized it, the government-led junkie finance of QE was reborn.

The story of the repo crisis deserves some explanation. Repos, short for Sale and Repurchase Agreement or Repurchase Operations, are essentially collateralized, overnight loans in which one party borrows reserves (cash) for a short period of time, usually overnight, and offers treasury bonds or other high-quality securities as collateral to the lender. If the loan isn’t renewed, the next day (or when the term is up in the case of “term repos”) the borrower repays the loan with added interest and repossesses their collateral.

This market in overnight deals offers a cheap way for banks to borrow when they need short-term cash, for example to meet their federally mandated minimum overnight reserve requirements — that is, the value of funds a bank must have on their books at the end of each day. And it gives lending banks with excess liquidity a chance to make a quick bit of profit without much risk or long-term commitment. It could be likened to plumbing: essential, ubiquitous, and unspectacular — until a pipe breaks and the ensuing flood destroys all your possessions.

Typically, repo transaction rates hover around the benchmark federal funds rate. But in the repo panic of September 2019 the repo rate suddenly shot up to as high as 10 percent in some trades, more than four times the Fed’s rate.

This happened because there was a sudden lack of liquidity: more institutions looking to borrow than there were institutions with extra cash to lend. The whole situation was odd, unexpected, hard to explain, and caused instant panic throughout the markets. At first, not even the Federal Reserve understood what was happening, but it knew it had to step in with an immediate $53 billion in emergency cash. Much more Fed money flowed in the following days.

The surge in repo rates caused by a mismatch between buyers and sellers was initially attributed to various combinations of the following factors: Corporate demand for cash to settle tax payments; a cash void created by a recent $78 billion of US Treasury offerings; a bank holiday in Japan; Dodd-Frank’s allegedly unjustifiably high reserve requirements; confusion over who actually owned which treasuries; and, most importantly, a lack of excess bank reserves to lend because of the Fed’s winding down of QE.

Indeed, when the dust settled, the Fed essentially admitted that the end of its mass purchasing of financial assets from private banks and corporations may have been “premature.” In other words, Wall Street was still addicted to government handouts.

By late December 2019 the central bank was loaning the repo market an average of $235 billion a day. The Financial Times estimated that the US central bank’s “gross cumulative support” for the repo market would top $11.5 trillion by the end of 2019.

As the FT put it: “The Fed did not just stabilise the repo market. Now, it is the repo market.” For the FT this was, “De facto nationalisation of the market.”

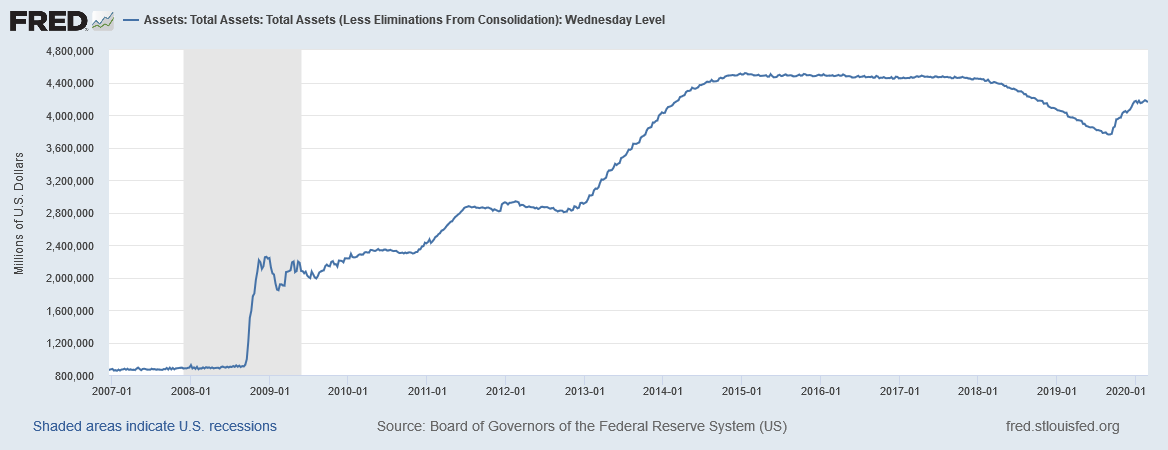

Consider the following chart of total assets held by the US central bank:

The blue line tracks the total assets owned by the Fed. The shaded area denotes the Great Recession. Notice the exponential surge in total assets as Fed purchases continue under three distinct QE programs.

Then in October 2014 the plateau begins when the Fed made its final massive purchases of private sector securities. The Fed maintained its bloated balance sheet of $4 trillion worth of assets until late 2017 when, believing that financial markets could finally stand on their own, it began selling off its holdings. That’s when the blue line starts to gradually slope down through 2018 and most of 2019.

Toward the end of the chart there is a sharp upward spike, which marks the September 17, 2019 collapse of the US repo market and the Fed’s resumption of massive purchases of private sector securities.

More recently, the central bank hinted that its emergency actions would be made permanent. It will create a standing “repo facility.” This is, essentially, to hook the repo market up to a dialysis machine. Currently, as of March 5, there’s close to $200 billion of repo on the Fed’s balance sheet.

In a final gift to rich speculators, the Fed is considering regular repo transactions directly with other securities’ dealers, particularly hedge funds. Unlike banks, which free market zealots and stone-cold communists alike can agree are essential to the working of a complex modern economy, hedge funds are purely parasitic. Owned by the ultrarich and engaging in some of the riskiest and most destructive forms of speculation, hedge funds serve no larger social purpose. They are to the rest of the economy, as tapeworms are to the human body — feeding off of the productive value created, nurturing themselves at the expense of the health of its host, the real economy. Absorbing hedge funds into “actually existing socialized finance” would be a remarkably outrageous twist of the screw.

Trump Hits the Gas Pedal

Even if this perverted quasi-socialism of the financiers could have been slowly undone, Donald Trump had no intention of doing so because titration off cheap credit and debt would risk a recession. And that would, in turn, risk Trump’s reelection. Instead, Trump did everything he could to pump up the asset bubble.

Most important was his highly regressive $1.5 trillion tax cut of 2017. Like every trickle-down economics ruse before it, the claim behind this tax cut was that it would stimulate the real economy. Money that would have been paid as taxes would now, the theory went, be invested in hiring new workers, buying new machinery, innovating new product lines, etc. In reality, this money was mainlined directly into financial markets.

The effective corporate tax rate was cut in half from 17.2 percent in 2017 to 8.8 percent in 2018. Tax rates on repatriated foreign profits were also slashed from 35 percent to 15.5 percent. And the $664 billion that firms repatriated from overseas tax havens did not go into higher wages or new investment in productive activities. Instead, the vast majority of that money helped fund 2018’s staggering $1.1 trillion in stock buybacks — the largest in history — thus inflating stock prices even more!

Then came three interest rate cuts in 2019, pushing yet more money into the financial markets. Fed Chair Jerome Powell had been trying to raise rates, but constant harassment from Trump, accompanied by a still precarious financial system, seem to have encouraged him to reverse course.

Zombie Firms and Mounting Corporate Debt

At the level of individual firms, this tsunami of money encouraged new rounds of dangerous borrowing. Since the financial crisis corporate debt has swelled to record levels — over $10 trillion, equal to 48 percent of GDP. Companies haven’t been this heavily leveraged since 2009, at the depth of the crisis. In January the New York Fed reported that only two US companies — Johnson & Johnson and Microsoft — still carry triple-A ratings.

According to the world’s largest asset manager, BlackRock, over 50 percent of this corporate debt is rated BBB, “the most vulnerable of all investment-grade debt in a recession.” Any rating below triple B is considered “non-investment grade” better known as “junk bonds.”

The IMF’s 2019 Global Financial Stability report warned, with robotic understatement, that these gargantuan levels of corporate debt will “amplify shocks” when crisis-provoked deleveraging cuts into investment and employment and significantly precipitates defaults.

The strange survival of the once iconic, now moribund JC Penney illustrates the insanity of the mounting corporate debt scene. Carrying $5.3 billion in leases and debt, and unable to cover its operating costs let alone turn a profit for most of the last decade, JC Penney’s last two CEOs have both made millions. One started at $20.44 million annually in 2014, failed at his job, and was replaced by another in 2018 whose starting package was $17.4 million annually.

Over the last decade the company has also: closed a quarter of its stores, fired 2,000 employees, and watched its stock fall from $29 a share to $0.60 a share. Its corporate bonds are now rated “Caa1” — that’s below classic junk bond levels.

Yet, in 2018 JC Penney sold corporate bonds offering a 9 percent return and thus managed to raise $400 million! How is this possible?

Financial Times columnist Robert Armstrong explained the mystery. “Economists and occultists have a word for things that walk the earth, dimly aware that they are no longer alive: zombies. After a decade of central banks pushing liquidity into the global economy, there are a lot more of them … reanimated by cheap money.”

JC Penney is not alone. A Bank for International Settlements (BIS) study found that the number of companies unable to earn enough money to cover their interest payments doubled from 3 percent in 2007 to 6 percent in 2016. When the next recession hits, these zombie firms will be, as Armstrong puts it, “forced into a rush of disorganised reorganisations and liquidations.”

Meanwhile, very little of this corporate leveraging has benefited workers. The overall labor share of corporate income — that portion of corporate income received by workers as wages and benefits — has not yet even returned to pre-recession levels.

Inequality and Bad Signs Ahead

Now that the latest experiment in extreme and financialized corporate welfare — junkie capitalism — is entering a new crisis, all signs augur something bad.

Airlines are expected to lose $100 billion this year. Oil prices have plunged by nearly 30 percent.The Purchasing Managers’ Index, which foreshadows trends in the manufacturing and service sectors, is looking weak.

Perhaps most ominous of all, bond markets have seen a “yield curve inversion” in which long-term Treasury bonds are in greater demand and thus offer lower rates of return (“yields”) than short-term Treasury bonds.

Normally, short-term interest rates are lower than long-term rates because the immediate future is typically more predictable and thus a safer bet than is the more distant future. When that relationship inverts it means investors are seeking safety and fear an imminent downturn. Yield curve inversions have preceded every recession since 1950.

Not only has the yield curve inverted, ten-year Treasury bond yields are now at all-time lows. On March 3, they fell below 1 percent for the first time ever; three days later they bottomed out at 0.74 percent. In other words, big investors are gathering in long-term government debt like apocalypse-focused “preppers” stocking up on ammo and Jim Bakker’s food buckets.

And now the longest expansion in US history threatens to end with hardly any discernible increase in the average worker’s standard of living. And the key lesson to learn is that this is because of policy, not despite it. The artificial inflation of financial asset prices through stock buybacks facilitated by low rates and daily Fed repo transactions has redirected money away from productive investment; that is, away from the real economy and the mechanisms, like good-paying jobs, by which markets could actually help working people.

As former president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Richard Fisher, put it a few years ago, the Fed’s policy has, “made rich people richer.”

In 2018 median CEO pay was $12 million a year. At the same time almost half of all workers — 44 percent according to a Brookings Institute study from late 2019 — work in low-wage jobs where the median annual earnings are a paltry $18,000 a year. The money created by the Fed under QE and the Treasury with TARP saved the banks but virtually none of it reached the average worker, unless in the form of more unsustainable medical, educational, and credit card debt.

The intervention by the Federal Reserve via QE was the largest economic stimulus program and — not by accident but by design — the largest single transfer of wealth, as well, in modern history. The prime beneficiaries of these seemingly obscure transactions between Wall Street and the US central bank were, also not coincidentally, the same institutions and networks of rich people responsible for the financial meltdown of 2008.

The financial markets are a highly modulated, planned, and protected system of relations between our quasi-public institutions and wealthy companies and individuals. The life support now being undertaken via repo injections is more of the same. The major difference is that it’s coming at a time when all signs point toward the inevitability of recession.

The “Purely Technical” Case for Egalitarian Redistribution

The tragedy in all this was that government action could have helped working people. In 2008 Congress could have used its financial power to bailout homeowners and thereby also revive the banks. The more recent deficit spending caused by Trump’s tax cut could have been better used to assist the scores of communities shattered by fourteen separate billion-dollar-plus catastrophic climate-related disasters that occurred in 2018. But that sort of policy would constitute “free stuff” and “moral hazard” and the slippery slope toward socialism.

Our point is not that the Fed should stay out of markets. The United States has always been an interventionist state and its political institutions share considerable credit for the awesome development of land, labor, and capital experienced over the last 200-plus years of its existence. Our economy, whether we like to admit it or not, is already “mixed.”

We support a full and conscious socialization of finance. But we want its power used to create social outcomes that are diametrically opposite of the disgusting regressive welfare for plutocrats that is America’s “actually existing socialized finance.”

What needs to change is how and for whom our public agencies shape economic activity. Instead of the large-scale asset purchases that allowed banks to resume lending to each other and re-inflate securities prices that disproportionately benefited the wealthy, the publicly controlled heart of finance could have been used to begin an egalitarian social transition of our economy.

Bizarrely, there is a possible silver lining in this gathering crisis. It is this: the old monetarist tricks are structurally played out. The Fed Funds rate is effectively at zero and the central bank has already taken over and semi-nationalized whole sections of finance. In the face of a new slump the cheap money strategy won’t work. The only polices that will revive growth will be the sorts that socialists are already demanding on purely ethical grounds: debt cancellation, free higher education, single payer health care, government jobs programs, and a Green New Deal to drive an energy transition.

Given the crisis of Junkie Capitalism and the reality of actually existing socialized finance for the 1 percent, these left-wing demands will soon take on a new purely technical utility. Nothing else will revive the economy.