Black Power in White Australia

The movement for Aboriginal self-determination has a rich history, steeped in the internationalism of anti-colonial struggles and black liberation movements throughout the world. We shouldn’t ignore it.

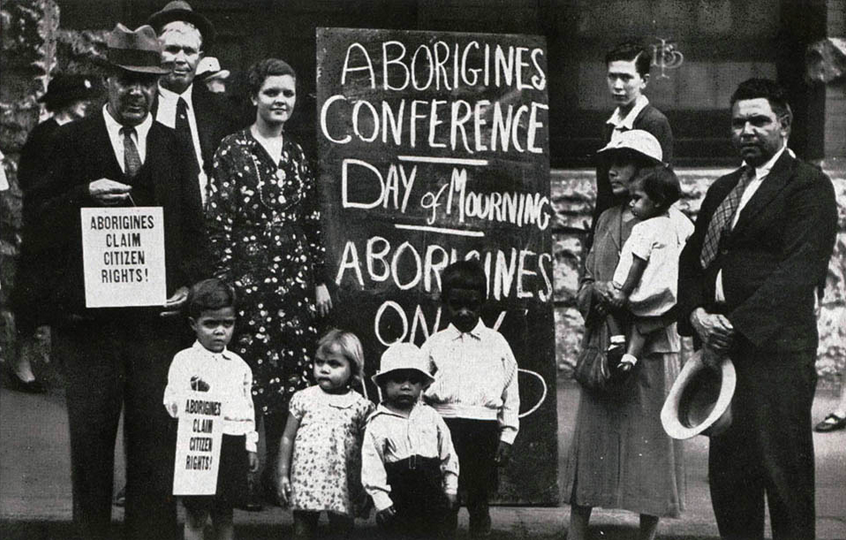

Day of Mourning, January 26, 1938, Sydney

- Interview by

- Sian Vate

Aboriginal people in Australia have been fighting for their rights since the British flag was first raised over Sydney Cove in 1788. In the radical ferment of 60s Redfern in Sydney, the movement for self-determination flourished. Fighting racist policy and attitudes at home, the movement was at the same time incorporating ideas from abroad, drawing on encounters with the Black Panther Party, African and Caribbean liberation movements, and indigenous struggles in North America.

In all this, Gary Foley has been a leading figure. An activist since his arrival in Redfern in the 60s, he is also a historian and teacher in Melbourne. In the lead up to Invasion Day, Foley sat down with Sian Vate to discuss the history of twentieth-century Aboriginal activism, and the ongoing struggle ahead. The two had first encountered each other at Melbourne University’s student union in the 2000s, where Foley had sometimes mentored a small collective of students from settler backgrounds dedicated to Indigenous solidarity, reading and organizing. His advice at the time: “Don’t go to Aboriginal communities and try to help out. Go back to your own communities and confront the racism there. Australia does not have an Aboriginal problem. Australia has a racism problem.”

You’re from Nambucca Heads on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales (NSW), which you left as a teenager to move to Redfern, in Sydney. There was a mass migration of Aboriginal people from rural NSW into Sydney at that time. What were the conditions like out in the rural areas?

As late as the 1960s, apartheid-style laws were still in force in several states. In New South Wales, around 50,000 Aboriginal people were confined to about forty so-called Aboriginal reserves, probably similar to places like Pine Ridge in America. They were regarded, in the eyes of some Aboriginal people, as concentration camps.

These reserves were government-run settlements in which Aboriginal people were forced to work. Aboriginal people who weren’t living on the reserves, who were trying to escape the apartheid system, were barred from entering to see their relatives. It was massively restrictive and oppressive, held in place by apartheid legislation.

In 1967, there was a historic referendum. Legally, the referendum was about transferring Aboriginal affairs from the states to Commonwealth control. As a result of the campaigning around it, though, the way that Australians understood the meaning of its question was, “Do you believe in justice for Aborigines, yes or no?” And the result was remarkable: 90 percent of Australians voted “yes.” It’s one of the most remarkable referendums in Australian history. And as a result, the NSW state government seemed to get itself in a huff. They decided, “Well, if people don’t want us looking after the Aborigines, we’ll pull out.” So they withdrew.

The impact of the referendum on Aboriginal people, in real terms, had nothing to do with what it was all about. After the NSW government suddenly closed down the system in 1968, about 50,000 Aboriginal people in rural areas were no longer provided with government rations. They had no access whatsoever to state government services. They were abandoned. At the same time, the rural areas of NSW were in recession, so there was no work. The direct result was a mass exodus from the country into Sydney.

I moved to Sydney in 1967 when there were about 1,500 Aboriginal people in Redfern. By 1969, this had grown to 35,000. All of a sudden, at the peak of the White Australia policy, you had this huge impoverished ghetto of landless refugees in the heart of big white Sydney. It was a very volatile situation. Out of this, the Black Power movement emerged.

At the time, young Aboriginal refugees in Sydney were developing more radical politics, partly as a result of their disappointment with the referendum?

Us young people, we were all living in Redfern. At the time, the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) were the acceptable, respectable wing of the Aboriginal political movement — the Australian equivalent of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). None of its leaders lived there. None of them were experiencing what we experienced on a daily basis. The same respected older leaders were the ones who had told us to get involved in the campaign for the referendum.

It’s not that the situation on the ground remained the same — things actually got worse. The exodus to the city after the referendum created problems of a different, but significant, nature. We began to read things like The Autobiography of Malcolm X. We felt betrayed by the older generation. Or, at least, we said to ourselves that the older generation’s tactics and strategies had clearly failed. And as young people, we were confronted with an in-your-face problem every day: namely, persecution by the NSW police. We needed to do something immediately.

We decided to go our own way. Paul Coe, a very charismatic young Aboriginal law student, came up to me and said: “I’m thinking about setting up a little discussion group to talk about what’s going on with the cops in Redfern.” And I said “sure,” because I’d been bashed rather seriously by some coppers two weeks before. So it began with a small group of probably five people at most. It was a little group, and we realized that if we were going to try to change what was going on around us, we needed to make ourselves a lot more aware than we were.

We needed to educate ourselves politically. We looked to examples from America, we looked at what was going on in Canada, and we developed some connections. We were very interested in what was going on in Africa because it was the era of decolonization. Some future African leaders and future ministers in independent governments were actually studying in Australian universities at the time, giving us the chance to meet.

We looked at ideas from around the world and drew from them. We looked to Cuba and we were really impressed with Che and Fidel because — to this day — they held the greatest military might in the world in abeyance. We were also interested in certain aspects of what was going on in China, especially the system of communes that we saw, at the time, as a potential way of organizing. We were developing a long-term plan for land rights, independence, and self-determination.

And that’s when you started using the term “Black Power.”

In 1967, Bruce McGuinness, who was then the director of the Australian Aborigines’ League (AAL) in Melbourne, and Bob Maza, who was the president, invited an otherwise obscure Caribbean academic by the name of Roosevelt Brown to give a talk about self-determination and resistance among non-white colonized peoples. In the course of his talk, Brown spoke about the importance of political independence, economic independence, and self-determination. He used the term “Black Power” to describe what he was talking about. It resonated with us.

Even so, Black Power would not have entered the Australian political language as dramatically as it did, had it not been for typical Australian journalists of the Rupert Murdoch variety sensationalizing it in the tabloids with headlines like “Black Power Fears.” At the same time, images of the Black Panther Party were filtering through to Australian TV audiences, who saw them as a threatening alternative to Martin Luther King Jr singing “We Shall Overcome.” The sensationalist Australian tabloid media had an easy time stirring up all sorts of unwarranted fears.

It’s like today in Melbourne. The same media is intent on stirring up fears about young immigrant Sudanese men and African gangs roaming the streets. It was a similar situation back then, only they were talking about Black Power, suggesting that Aborigines were training with guns and all that sort of nonsense.

You also made connections with African American soldiers fighting in Vietnam who pit-stopped in Sydney.

Yes, suddenly Sydney became the focus for thousands of American soldiers shipped in from Vietnam for ten days’ leave before being sent back to the jungles to be shot up by Ho Chi Minh and his brothers. A significant number were African American. We realized that the American military was using poor African Americans from the ghettos as cannon fodder in Vietnam. These troops brought personal, firsthand accounts of what was going on politically in the ghettos of Oakland, California, and Harlem, New York, and elsewhere.

They also brought political literature that was unavailable in Australia the time, including The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Seize the Time by Bobby Seale. A strong interest in the African American political scene grew in Redfern. When we looked at the police harassment we faced, we realized that the Black Panther Party was talking about the same kind of harassment in Oakland. We regarded our situation as almost identical to theirs: impoverished black communities were being intimidated and harassed by police forces. So we looked at what the Black Panthers had done. We adopted and adapted some of their tactics and strategies into our movement.

In 1972, amid widespread radical action — not just Aboriginal action, but also mass anti-war protests, feminist action, environmental action, and trade union militancy — the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established on the lawns of Parliament House in Canberra. What led to the Embassy’s set up?

The Aboriginal Embassy protest in Canberra, which took place between January 27 and July 30, 1972, was the most significant Aboriginal political action of the twentieth century.

In the lead-up to it, the Black Power movement had been calling major marches and campaigns for land rights in the eastern state capitals. And these demonstrations were making the McMahon government nervous. Throughout 1971, the cities saw nonstop demonstrations. They happened on a weekly basis, and they were growing. One result was a growing debate about land rights in the mainstream media and elsewhere. All the while, the government maintained a consistent line, that assimilation was the only option for Aborigines.

Assimilation had been official, bipartisan government policy since Federation in 1901, since Australia became Australia. The whole idea of assimilation is genocide. Its desired end goal is that, eventually, there are no natives left. It was a genocidal policy.

The other thing that happened in 1971 was that the white, racist South African rugby team toured Australia. South African apartheid was still alive and well, and the tour attracted major protests. Aboriginal political activists challenged the anti-apartheid activists here, saying: “Support us. How can you fight racism over there but not here?” It worked. The numbers in our demonstrations grew.

At the end of 1971, Billy McMahon — the nervous, tragic little man who was then prime minister — made a fateful decision. Given the public uproar about land rights, he decided that his government must make some sort of definitive policy statement. His worst mistake was to make this statement on the most sensitive day in the political calendar for Aboriginal people: January 26, Invasion Day. The Day of Mourning. But not only did Silly Billy McMahon make his ill-fated statement on that day, his statement rejected Aboriginal claims for land rights. He said that his government would never grant Aborigines land rights.

So that same night in Redfern, a meeting was held. We decided that four of us should be dispatched to Canberra to set up a protest on the lawns of Parliament House. In the first instance, we only intended for four guys to go. We’d arranged with the Canberra newspaper to have a photograph taken. We figured they’d get arrested the same night and that we’d bail them out of the cells the next day.

But when the Canberra constabulary arrived, they told the guys that they weren’t breaking any laws. They said it was legal to camp on the lawns of Parliament, as long as no more than eleven tents go up. So we’d stumbled upon a loophole in Canberra’s law. The next day, a tent was set up as the office, and the Embassy remained on the lawn for the next six months.

When Gough Whitlam, then opposition leader, visited the embassy, he made a speech about giving land back to Aboriginal people. Paul Coe jumped up and challenged him, saying: “Hang on, isn’t the Labor Party’s policy assimilation, the same as the Liberal-Country Coalition? Assimilation equals genocide. Don’t come here and bullshit us, Mr Whitlam.” After that, Whitlam went away and changed the Labor Party’s policy to support land rights for Aboriginal people.

This was the first time since 1901 that bipartisan support for Aboriginal assimilation was broken. It was the Embassy that provoked Whitlam to do that. It was incredibly significant.

The Embassy also made the whole world aware of what was taking place in Australia. During those brief six months, journalists from seventy countries reported on it. It put Aboriginal affairs on the national political agenda and into the front-page headlines as an issue, where it has remained to this day.

In concrete terms, what were you fighting for? You weren’t just out there to change laws or express yourselves?

We wanted much more than that. Unlike the generation before us who wanted citizenship and the right to vote and things like that, we developed an analysis that drew from Native American political ideology, but which was grounded back home. We came to see ourselves as independent nations of people, and that as such, we were entitled to certain areas of land in NSW. We talked about the old reserves, which, despite having been abandoned, were still owned by the government. We demanded they give us that land.

We developed a philosophy stressing self-determination as well as political and economic independence. We believed that the basis for any form of economic independence was land. The proposition we made did not involve dislocating any settler colonials. We thought, “Oh, fuck them, we’ll let them go.” Still, the proposition gave us significant areas of land — land that many of our people still lived on anyway.

We also wanted money. We said to the government: “Call it back rent, call it compensation, call it anything you like.” But we wanted a significant amount of money to enable communities to develop economic enterprises that weren’t in conflict with their basic cultural values, but which could generate employment, bring resources into the community, and enable them to then upgrade their infrastructure. Our aim was to develop sufficient economic independence to be able to secede from Australia. The ultimate ideal for us was always secession.

I don’t consider myself an Australian; I’m a member of the Gumbaynggirr nation, which predates Australia by something like 80,000 years. Why would we want to be part of this nation called Australia that has historically treated us so badly? This was the ideal for us. I don’t think I’ll see it in my lifetime. But I know that there are Aboriginal groups around Australia who are capable of ultimately attaining that goal. If there’s the political will among their people, they should secede and become independent nations in their own right.

The radical internationalism of the Black Power movement is really striking. Your doctoral research on Aboriginal political organizing in the twentieth century shows that it’s part of a tradition that reaches back as far as the early 1900s.

That’s right. In 1907, the legendary Afro-American boxing champion Jack Johnson attended an event on the Sydney waterfront held by an organization called the Coloured Progressive Association. Back then, he was the most hated man in the world — he held the World Heavyweight Championship, and the white supremacists of the settler-colonial societies couldn’t find a white man capable of beating him. During the visit, two Aboriginal wharf laborers, Tom Lacey and Fred Maynard, met him and were inspired. Lacey and Maynard’s ongoing association with the waterfront also allowed them to meet visiting African, African American, and West Indian sailors, and they were developing their political awareness.

In 1914, Marcus Garvey, the father of the international black consciousness movement, created his organization, the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Garvey’s strategy was to recruit African, West Indian, and African American sailors, and to tell them that wherever they went in the world, wherever their ship pulled into port, they should set up a chapter of UNIA. It’s one of the more remarkable moments in Australian history that in 1920, in still-white-supremacist Australia, a branch of UNIA was founded on the Sydney waterfront. Lo and behold, Maynard and Lacey were members of that branch.

And as a result, Maynard and Lacey went on to set up the first modern Aboriginal political organization, the Australian Aboriginal Progress Association (AAPA). It’s an extraordinary thing. Most historians don’t realize that the first modern, political Aboriginal resistance organization, set up in 1924, was inspired by the teachings and writings of Garvey. But as I’ve always said, that was the beginning; the first significant engagement by Aboriginal activists with international ideas of independence, self-determination, black consciousness, black nationalism — the works.

The AAPA only lasted three years before it was suppressed politically by the NSW police and authorities. It wasn’t till 1936 that two more significant Aboriginal political organizations emerged: in Victoria, the Australian Aborigines’ League (AAL) was set up in Fitzroy, and a year later, in NSW, an organization called the Aborigines Progressive Association (APA) was founded, which followed on from the earlier AAPA.

These were the organizations that held the first Day of Mourning in 1938, which protested the Australia Day celebration on January 26 — the date that the British flag was first raised over Sydney Cove.

Yes, 1938 was the sesquicentenary — the 150th anniversary — of the arrival of the first British settlers in Australia. So the NSW government decided to have a big celebration in Sydney — including tall ships sailing into Sydney Harbour and all manner of nationalistic nonsense. Like what happened in 1988, the government spent millions of dollars reenacting the arrival of the First Fleet, including forcing a group of Aborigines they’d shipped in from northern NSW to take part, who they’d coerced into cooperation by threatening to cut off their rations.

Remember, in 1938, Australia was still very much an Anglophile nation — most Australians thought of themselves as British rather than Australian — so it was a nightmare event of monumental proportions. Also, because of the White Australia policy, Sydney was very white, as it still was when I went there in the ’60s. As all of that was going on in various parts of Sydney, the Aboriginal organizations, the AAL and APA, joined forces to mount a protest. They held a meeting in a hall in Sydney, made speeches, and gathered out front with placards. The most important thing about that 1938 protest is that it was the first time an Aboriginal protest had been noticed both locally and internationally.

More important, William Cooper of the AAL deemed January 26, 1938 to be a Day of Mourning. Ever since, on January 26, Aboriginal people have mounted various forms of protest. And it’s gaining momentum. Recently, the activities of the young mob from WAR (Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance) have increased awareness about why celebrations on that day are particularly offensive to Aboriginal people. If we can get 80,000 people in the streets marching against Australia Day in Melbourne, like we did last year, it’s a sign of a shift. I think that the younger generation of Australians are a lot more conscious of these issues than older generations were.

Your doctoral research has also focused on how the trade unions and the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) formed genuine collaborations with the Aboriginal movement, right up to the 1970s.

The Aboriginal resistance received the strongest solidarity and material support from the trade union movement. In 1946, the Wharfies’ and the Seamen’s Union strongly supported the Pilbara strike, the longest strike in Australian history, which was mounted by a large group of illiterate Aboriginal stockmen in remote parts of North Western Australia. It’s a historic strike, and it was strongly assisted by the trade unions.

Much later, one of the most important land-rights struggles occurred in Wave Hill in the Northern Territory, where another group of Aboriginal stockmen walked off and challenged the owner of the land, a wealthy British aristocrat named Lord Vestey. The Gurindjis were penniless stockmen who worked for rations rather than wages, and they walked off the station. Their strike lasted nine years, and it eventually won. To survive that long, the Gurindjis needed support from a wide range of groups around Australia. Once more, in particular, the trade union movement came to the fore. The National Wharfies’ Union levied its members to provide the money that kept the Gurindjis going.

In general, the trade union movement — or at least the left-wing trade unions — always strongly supported the Aboriginal struggle for justice. The Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) in NSW, led by Communist Party official Jack Mundey, was also a strong supporter. In fact, the only person to go to jail as a result of the Tent Embassy protest was a white BLF member. There’s a long history of those sorts of expressions of solidarity between various parts of the working class in Australia and the Aboriginal movement. And during the 1940s and ’50s, the CPA was the only political party that supported Aboriginal land rights. It had a very strong platform supporting our political independence.

To return to Redfern in the 1970s, in addition to the political and community organizing led by the Black Power movement, there was also a lot of cultural work, including the National Black Theatre and the comedy sketch show Basically Black. During this period, it seems like Aboriginal art came to take a central place in Australian arts overall, which is something that hasn’t changed.

The Black Theatre emerged as a means of communicating our political message in the 1970s, but I’d argue that the broader appreciation and awareness of Aboriginal art took root in the ’80s. In 1982, I became the first Aboriginal director of the Aboriginal Arts Board, which had been set up by Gough Whitlam ten years earlier. In its first decade, the board had been run by white people, and most of the money that it was dispensing was going to non-Aboriginal organizations and individuals.

Chicka Dixon and I put a stop to that. Chicka became the chair of the board, appointed by Bob Hawke. He appointed me as director, and we transformed the appreciation of Aboriginal art. You can trace the beginnings of this huge international awareness of Aboriginal art back to that period of the Arts Board.

To this day, the most successful exhibition to have ever left Australian shores is the Aratjara exhibition. It was organized by me and a Swiss-German artist, Bernard Lucia. It was significant because we argued in Europe that Aboriginal art should be placed in the modern art museum, and not in anthropological and ethnographic museums. That’s now become an international standard. It was also the first time for a major exhibition of Aboriginal art to include both contemporary urban and so-called traditional art. Many of the artists who we promoted in that Aratjara exhibition, like Richard Bell, went on to be exhibited in some of the most prestigious museums in Europe. Aratjara broke ground in a range of ways.

The fight for Aboriginal self-determination and land rights is ongoing and, as you’ve pointed out, the same powerful, racist forces in Australia are still in play today. Not much has changed in that sense. Yet, at the same time, if you’re born in Australia after the 1970s or ’80s, I’d argue, you’re aware of Aboriginal identities and cultures in ways that earlier generations, for the most part, weren’t. Black Power is a big part of that.

That’s right. It shows that in the late 1960s and ’70s, Redfern was, in certain ways, a dynamic and really exciting place, despite the fact that everyone was impoverished. The 35,000-strong community that grew there in just three years created, unwittingly, a place that spawned all sorts of really exciting stuff. For example, we introduced legal aid to Australia fifty years ago this month, in 1970. The Aboriginal Islander Dance Theatre was set up by Carole Johnson during that period, and out of that evolved the theater we were doing, and the Bangarra Dance Theatre.

It was a sudden burst of creativity. That’s why the government felt compelled to break up the community as early as 1975. They did it surreptitiously by introducing new public housing regulations in inner Sydney. They said that Aboriginal families applying for public housing — which was most of them — were not to be housed in the inner-city estates. Instead, they were to be sent into the western suburbs. The policy set a limit of one family per street. In other words, they enforced and imposed assimilation, resulting in a deliberate, modern-day dispersal of a strong Aboriginal community.

The same thing happened in Fitzroy in Melbourne — only it was achieved by gentrification, and not by government intervention. The end result was the same: today, the strong Aboriginal community that once existed in Fitzroy and Collingwood is no longer there.

When Australians talk about the issue, they sometimes say: “Oh, but all of these things that happened to you Abos happened a hundred years ago, it’s got nothing to do with us.” They should think about what’s going on around them today — the ongoing effects of settler colonialism. Australians need to wrap their heads around the notion of intergenerational trauma. They have shown they can understand it with respect to the Jewish community and the things that happened to that community a mere eighty years or so ago. But they can’t understand the similar things affecting Aboriginal people through multiple generations.

This is partly the reason why so many Aboriginal people are incarcerated today. As you know, all of these things are interconnected.

You teach Aboriginal students, who look up to you as somebody who has continued the fight, in spite of the difficulties. What do you say to students who are thinking about how they’re going to focus their efforts to survive and fight?

I would say to them: I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat. I don’t usually quote old miserable fascists like Winston Churchill, but in this instance, it’s accurate because anyone, any young person who wants to become a political activist, needs to realize that in order to stay true to your principles, you’re going to end up living a life of poverty. It will be a difficult struggle because you’ll always be outside the tent pissing in. And that’s a preferable place to be, even though it can be extraordinarily difficult over extended periods of time. It is a tough life you choose, if you go this way.

It seems to me that part of the payoff is comrades.

Absolutely.