The Corporate Media Has No Idea What to Do With the Fact That Bernie Sanders Is Jewish

The mainstream press loves attacking Bernie Sanders for either being too Jewish or not Jewish enough. It's a cynical ploy to undermine his unapologetically left-wing campaign.

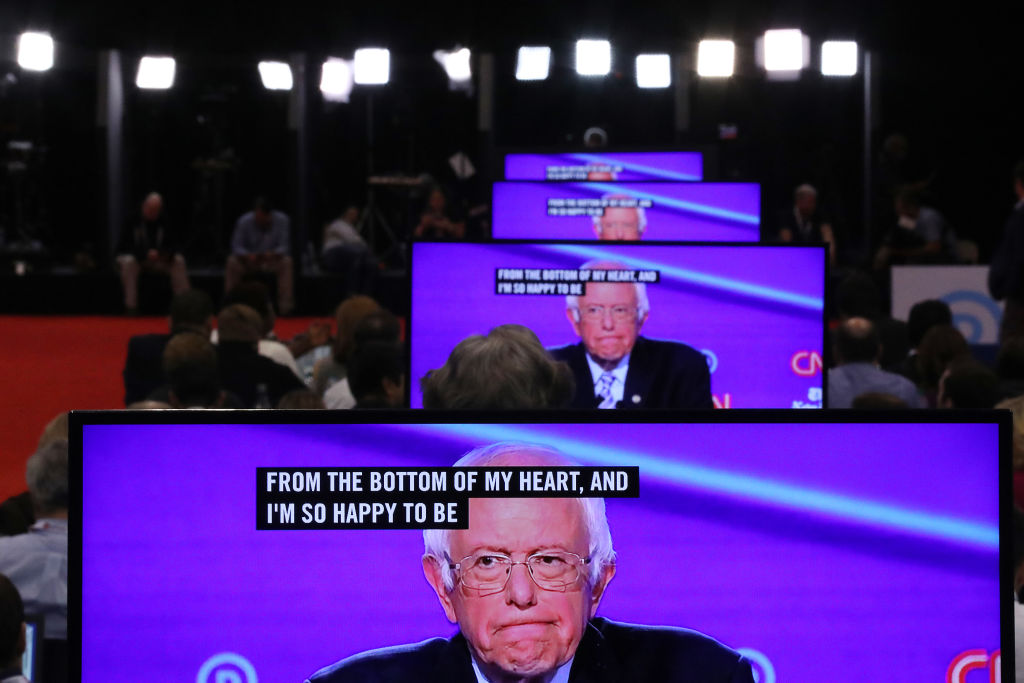

Sen. Bernie Sanders appears on television screens in the Media Center during the Democratic Presidential Debate at Otterbein University on October 15, 2019 in Westerville, Ohio. Chip Somodevilla / Getty

In 2016 Bernie Sanders became the first Jewish American to win a major party presidential primary election (New Hampshire). If he wins the Democratic presidential nomination next year, he will be the first Jew in US history to do so. If he wins the general election — well, you get the idea.

Sanders prefers to run on a message of universality, but his identity is impossible to ignore in the press, so it makes sense that he addressed the issue himself in a recent essay in Jewish Currents entitled “How to Fight Antisemitism.” The press reaction to the piece, however, has been just another example of how Sanders’s Jewishness gets weaponized against him. It’s not that mainstream attacks on Sanders are antisemitic, but rather that whether he is “too Jewish” or “not Jewish enough” are being used as cynical tools against him.

Sanders’s essay starts off by discussing last year’s Tree of Life massacre, the deadliest act of antisemitic terrorism in US history. Then, after reflecting on his experience with collective farming in Israel, Sanders invokes a discomfort some Jewish socialists have felt in left spaces — a sense that antisemitism is seen as separate from other oppressions, when it should be considered part of the white supremacy and racism the Left aims to defeat. As Jewish protesters point out the parallels between ICE’s concentration camps and Nazi roundups of Jews, and we watch Jewish anti-Trump activists form protective circles around their Muslim counterparts, Sanders’s call couldn’t be more timely.

But press commentators in the US Jewish press and the Israeli media have a different idea. At Ha’aretz, Anshel Pfeffer pooh-poohed the essay, largely because Sanders denounced antisemitism as a right-wing form of bigotry that the Left should oppose. Insisting that antisemitism cannot be perceived as a cousin of other oppressions and must stand alone, Pfeffer seemed to want to reposition the struggle against antisemitism as about one thing: protecting Israel. “The fight against anti-Semitism,” he wrote, “is on behalf of all Jews, including those who hate Palestinians, or just fear that giving them even an inch will doom Israel.”

The Forward ran several rebuttals to Sanders’s essay, including one by Izabella Tabarovsky, who claimed that Sanders’s universalist call veered too close to the Soviet failures that inspired many to emigrate. Of course, it’s a truism in US media that it’s the American identity — not Soviet citizenship — that melts away race and ethnicity to unite people. It’s even America’s national motto: E pluribus unum (“From many, one”). But when Sanders invokes the same principle, it’s an opportunity to red-bait him.

Often, the collective complaint from the mainstream is that Sanders doesn’t account for antisemitism from the Left. That’s a loaded critique, too, as it draws a false equivalency between violent right-wing anti-Jewish terrorism and criticisms of Zionism.

And in the non-Jewish press, there’s always been curious phrasings about Sanders’s demeanor that sound like dog whistles. The New Yorker, Washington Post, and the New York Times have all cast him in the role of an angry, “Old Testament” prophet — the last of which described him as being “as wild-eyed, scowling and angry as an Old Testament prophet on the downside of the prediction racket.”

Addressing the anti-Sanders bias in the US press earlier this year, Katie Halper noted: “When MSNBC legal analyst Mimi Rocah said that Bernie Sanders ‘made [her] skin crawl,’ though she ‘can’t even identify for you what exactly it is,’ she was just expressing more overtly the anti-Sanders bias that pervades the network.”

Halper, who has written sharply about the politics of antisemitism, could take this even further. The rhetoric that Sanders is physically creepy or repulsive — divorced from any substantive take on his beliefs — combined with complaints that he’s too loud and assertive, is the kind of personal insult that’s almost exclusively used against an “other”: minorities or immigrants, people whose perceived peculiarities offend the sensibilities of the majority.

In fact, in the last election cycle, I noted at the Forward that press coverage of Sanders had slipped into a variety of anti-Jewish tropes, such as false assertions of dual loyalties and attempts to paint his younger self as dangerously lascivious. If Halper’s reporting is any indication, not much has changed.

To be clear, what’s happening isn’t an anti-Jewish conspiracy against Sanders; it’s more subtle and banal. When Sanders talks about Jewishness or his commitment to fighting antisemitism, he takes heat for being the wrong kind of Jew, as if he isn’t really Jewish — unlike, say, Michael Bloomberg, who is just as nonobservant as Sanders but is “embraced for his unwavering support of Israel and his generous donations to Jewish causes.” When Sanders sticks to his universalist message, the press dips into its goodie bag of accusations in a way that seems intended to discredit or at the very least distract from Sanders’s left-wing campaign. Again, the problem isn’t that the press dislikes or fears his Jewishness, but rather that his identity at any given time can be exploited as a way to undercut his ideas on race, class, or foreign policy.

We should be on the lookout for those opportunistically deploying such tropes as the presidential race continues. After all, these types of tactics are almost exclusively used against candidates promising fundamental political change.