Why Bernie Sanders’s History of Racial Justice Activism Matters

Shaun King on the importance of Bernie Sanders's lifelong dedication to anti-racist struggle, from the 1960s to today.

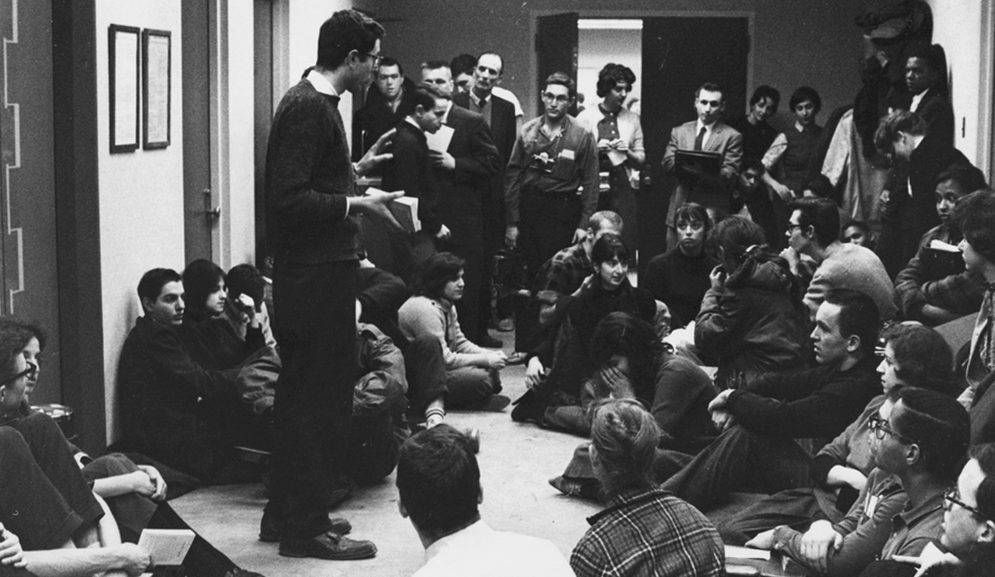

Bernie Sanders speaks to students on the first day of a sit-in at the University of Chicago in 1962. University of Chicago Photographic Archive, Special Collections Research Center / University of Chicago Library

I reject the idea that who Bernie Sanders was in the 1960s is irrelevant. Who you are and what you do, what you fought for, and who and what you fought against, is always relevant. Twenty and thirty and forty years from now, when people step up to lead, and run for office, what they did and where they were during the Black Lives Matter movement will mean something. If what Bernie did in the sixties doesn’t matter now, then what you are doing right now doesn’t matter. But you and I know it does.

Dr King once said, “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

Just a teenager, Bernie Sanders moved from his hometown of Brooklyn to Chicago at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. It was the most tumultuous and challenging time this nation had faced since the Civil War a hundred years earlier.

And most Americans, particularly most white Americans, remained silent. It was that silence, in the face of lynching, in the face of water hoses, in the face of bombings of homes and churches, in the face of assassinations, in the face of attack dogs being released on children, it was white silence that broke the heart of Dr King as he languished in a Birmingham jail (read his letter here). It was that silence that he found told us more about the soul of America than the brutality and evil of this place.

Bernie loved Dr King. And long before we used the phrase, Bernie had the notion that he needed to use his own white privilege to fight back against racism and bigotry and oppression and inequality. And that desire to hold this country to a higher standard began to well up in Bernie as a young student at the University of Chicago. He became the chairman of the university chapter of the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) and merged the group with SNCC — the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Bernie literally helped lead the first known sit-in in at the University of Chicago, where thirty-three students camped outside of the President’s office — protesting segregating housing on campus.

Disturbed by police brutality in Chicago, Bernie once spent the entire day blanketing the city with flyers on the issue — only to notice that he was being tracked by police who were following him and taking the flyers down.

Bernie hates telling these stories and has resisted using them for political capital across the years — even when advisors and others have told him it would boost his profile — he has refused. He does what he does because he cares. When I introduced Bernie at a rally in Los Angeles by sharing many of these stories, his own family came to me in tears saying that even they had never heard them before. He has always felt that what he did during the sixties paled in comparison to those who were beaten or lost their lives — and so he has kept some powerful stories to himself.

It’s cool for people to say, “I marched with Dr King” — and Bernie actually did attend the March on Washington, but he did so much more than that. This is not some exaggerated myth. This is the origin story of a political revolutionary.

In 1963, nine years after Brown v. Board of Education, the white power structure in Chicago was still fighting against school equality like their lives depended on it. They literally treated Black school children like they had the plague. Not only were Black schools woefully underfunded, they were overcrowded and bursting at the seams.

At the same time, with every single Black classroom in Chicago past capacity, sometimes with school children sharing chairs and desks, a report found that 382 white classrooms across Chicago were completely vacant.

Mayor Richard Daley, who ruled Chicago with an iron fist, still hailed as a Democratic hero to this day, and School Superintendent Benjamin Willis, decided that before they would let a single Black child fill one of those vacant white classrooms, they would start putting raggedy trailers on the playgrounds and in the parking lots of Black schools, and put Black school kids in those trailers instead. They were scorching hot in the summer and bitterly cold in the winter. They were so cheap and poorly constructed that they often had holes in the floor — allowing rodents to come in and out at will. And those awful trailers became known around Chicago as Willis Wagons, named after Benjamin Willis, the school superintendent.

In August 1963, just days before the March on Washington, the City of Chicago was about to install some more Willis Wagons for Black school children, and a brave interracial group of local activists and organizers decided to put their bodies on the line to block the installation of those trailers. They stood in front of bulldozers. They chained themselves together. Out of his reverence for what activists in the South were doing, Bernie has long since downplayed this demonstration, but it took so much courage.

Bernie Sanders chained to Black women at the protest of Willis Wagons.

Bernie, side by side with Black women, chained to them, refused to move. Even when the Chicago Police told him they would arrest him and forcefully remove him, he refused, and even when they decided to arrest Bernie and pick him up and carry him out of that parking lot so they could install those Willis Wagons, he kicked and screamed and resisted the entire way. Have you seen that photo of them carrying Bernie? I love it. And that photo, to me, is not just who Bernie was, it’s who he’s been his entire life.

To say that all of that means nothing is fundamentally preposterous. It means everything. Bernie was a protestor. Bernie was an activist. Bernie was an organizer. And he is literally the only person in the United States Senate with this story. When he retires, he will be the last activist from the civil rights era in the United States Senate.

He did much more than this. I could tell you a dozen more stories, but I wanted to tell you who Bernie was when it counted, before we knew him, before he ever ran for office, before he was ever a national figure. He was a fighter. He has always rejected the status quo. He spoke out against apartheid in South Africa before it was popular. Today, he speaks out against the apartheid-like conditions in Palestine — even though it’s not popular to do so.

It takes guts in this country to refuse to be a Democrat or a Republican. It takes guts to do what Bernie did earlier this month in California, to stand outside of Disneyland, and tell the country that one in ten of their workers have been homeless in the past two years, that two out of three of their workers are food insecure, and three in four don’t even make enough money to afford their basic needs — while their CEO makes hundreds of millions of dollars and goes around hinting that he might run for president. Bernie Sanders is standing alone calling out Jeff Bezos for his extreme wealth while Amazon workers are struggling with basic needs all over the country.

I campaigned hard for Bernie to be president. I believed he could beat Donald Trump and I believe he still could, but nothing touched me more about Bernie on the campaign trail than his love and support of my friend, Erica Garner. I genuinely think her campaign ad for Bernie was the most compelling political ad of 2016. It disturbed the political establishment so much that Harvey Weinstein wrote Clinton’s campaign and urged them to find a way to shut Erica up.

Erica was forced into becoming a revolutionary freedom fighter after the NYPD murdered her father in cold blood. Erica had a bullshit radar and could see BS coming from a mile away. So many politicians had looked her in her face and lied — over and over again — saying what they were going to do to bring her family justice. And Bernie was literally one of the only political leaders she trusted.

She loved Bernie so much. Erica gave her life fighting for justice for her family. And my very last conversation with Erica before she passed away was all about how much we both loved Bernie and believed he could’ve beaten Trump. Watch the video again. She loved Bernie because she knew he was really just an activist at heart.

I think we need a radical reconsideration of who Bernie is — more faithfully centered in who he was when it mattered, and who he has been for generations now.