The FBI Is Not Your Friend

There's nothing to celebrate about the FBI — it isn't, nor has it ever been, a guardian of democracy.

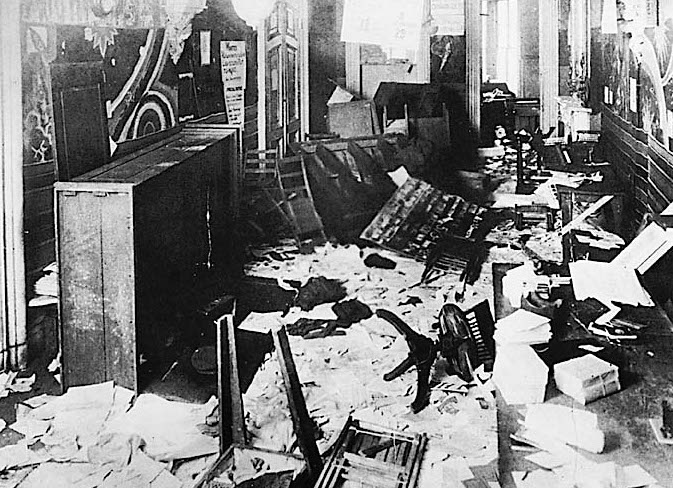

A ransacked Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) office during the Palmer Raids.

Donald Trump’s decision to fire FBI director James Comey is an alarming, if characteristically incompetent, move by a president who seems to view even the smallest challenge to his power as unacceptable. At best, it’s an attempt to punish someone Trump sees as insufficiently loyal. At worst, it’s a clumsy and self-defeating attempt to cover up a crime.

Given the circumstances, it may be tempting to treat Comey as a saint, and his Bureau as some kind of exalted institution beyond time, space, and politics. Jimmy Kimmel has already printed shirts reading “James Comey is my Homey,” while John McCain has called him “arguably the most respected person in America.” Columnists, politicians, and others have lauded the FBI for its supposed neutrality, independence, and non-political nature. Comey himself, in his farewell letter, described the FBI as a “rock for America” and a “rock of competence, honesty, and independence.”

To be sure, the FBI has done some praiseworthy work. It’s investigated white supremacist infiltration of police departments. It’s arrested right-wing terrorists bent on attacking minorities. And even in its worst days, under J. Edgar Hoover, it took on the KKK and investigated the murders of civil rights activists in the South.

It’s also true that Comey seemed genuinely interested in making himself and the Bureau neutral arbiters above partisan concerns. His inability to navigate the general election minefield wasn’t for lack of trying.

But we shouldn’t allow any of this to cloud our vision: the FBI has a long history as an intensely political organization, often undermining the very values it claims to stand for — and Comey’s leadership didn’t change that.

Comey’s FBI

Part of the reason for Comey’s reputation as an independent straight shooter, even hero, is his time at the Justice Department during the Bush administration.

Acting as deputy attorney general, Comey refused to extend Bush’s illegal warrantless domestic spying program and raced to then-Attorney General John Ashcroft’s hospital room to prevent Alberto Gonzales from getting a barely moving Ashcroft to sign onto it over Comey’s head. While admirable, it’s helped contribute to a gilded image of Comey that was only dented by his actions during the election.

After his ascension to FBI director in 2013, Comey spent months trying to force Apple to undermine its own encryption so that the FBI — and potentially numerous other law enforcement agencies — could access the content in people’s phones. Although this started with the San Bernardino shooters, it was part of a long-planned campaign to create a civil-liberties-shredding precedent. For years Comey fearmongered about the dangers of encryption, claiming that law enforcement was “going dark” because of it, warning that it “threatens to lead us all to a very, very dark place,” and cautioning that he didn’t know how much longer the FBI could thwart ISIS plots while such privacy protections existed.

Comey, like many in the intelligence community, wanted to prosecute WikiLeaks and Julian Assange under the Espionage Act, arguing that their actions were simply “intelligence porn” and distinct from “legitimate” journalists who publish information to educate the public. Assange and WikiLeaks’ shortcomings notwithstanding, this is a dangerous line to take. As Elizabeth Goitein of the Brennan Center has pointed out, it creates a line between “good” and “bad” journalists, the arbiter of which is the Justice Department.

Comey was also a high-profile booster of the “Ferguson effect” or as he called it, the “viral video effect.” He claimed that a spike in murders in 2016 was due to the greater scrutiny police had come under in the wake of shooting scandals, leading officers to shy away from necessary police work lest they end up on YouTube. By his own admission, this wasn’t based on any statistics, but on what some law enforcement officials had told him. Yet an FBI report released two weeks ago, while Comey was still FBI chief, persisted with this narrative, faulting the media and Black Lives Matter for the increase in police killings last year.

The Bureau engaged in still more unseemly activities with Comey at the helm. It surveyed and videotaped various Black Lives Matter protests from the sky and tracked a Black Lives Matter protest in Minnesota in December 2014. It sent agents from its Joint Terrorism Task Force to investigate Standing Rock protesters and paid a visit to left-wing activists in Cleveland prior to the Republican National Convention, which those on the receiving end perceived as an intimidation attempt. It launched a community initiative aimed at preventing “radicalization” that morphed into an intelligence gathering program on Muslims, and, most recently, carried out a nationwide sweep of Muslims in the lead-up to Trump’s election.

The agency’s relationship with Muslims has been no better internally. Muslims in the FBI report a pervasive anti-Islam culture, with one analyst losing his job after a Kafkaesque process where he came under suspicion for following his training and refusing to out himself as an FBI agent at a French airport. And Comey, refusing to bow to critics, maintained the FBI’s policy of continuously scrutinizing foreign born agents.

Yet despite the pervasive anti-Muslim bias, despite the attacks on activists, despite the “Ferguson effect” histrionics, Comey’s tenure was actually tame compared to previous decades. A quick look at the FBI’s history reveals an agency that, far from being a “rock” of honesty and independence, has often gone even further than it did under Comey in trying to stamp out dissent.

Appetite for Order

The FBI’s obsession with order is ingrained in its DNA.

Before the agency’s formation, the Justice Department employed the Pinkerton detective agency to infiltrate, sabotage, and suppress labor activity and generally protect private businesses from the threat posed by calls for fair wages, eight-hour days, and safety standards. The Pinkertons’ work became increasingly violent, with agents shooting protesters and participating in the brutal vigilante murders of labor organizers like Frank Little.

Little wasn’t an outlier: indeed, it was Robert Pinkerton, agency founder Allan Pinkerton’s son, who suggested that radicals “should all be marked and kept under constant surveillance” following the assassination of President William McKinley.

The FBI took much from the Pinkertons, including its identification methods (fingerprinting) and its centralized national criminal identification database. It also inherited the Pinkertons’ anti-radical bent.

Theodore Roosevelt’s initial attempt to form a national police force under the Justice Department had actually been blocked by Congress, out of a concern that it would be a tsarist-style “secret police force” used to spy on Americans. Congressmen warned of a “system of espionage” and a “central police or spy system in the federal government” that would undermine civil liberties. Roosevelt’s attorney general, Charles Bonaparte, assured Congress that “nothing is more injurious in that line and nothing more open to abuse than the employment of men of that type.”

But Roosevelt and Bonaparte set up the Bureau anyway in June 1908, a month after Congress adjourned.

Initially, the Bureau did focus on relatively mundane interstate crimes. Within a year of its creation, though, the Bureau’s chief directed a special agent to use an informant in a socialist organization to gather more information about a particular socialist figure.

The advent of World War I pushed the repression to new heights. With all levels of the Justice Department mobilized to root out disloyalty, radicalism, and anything else viewed as counter to the war effort, the Bureau was soon going after draft-dodgers, foreigners, pro-German and pro-Irish activists, labor unions, various political radicals, and anyone else who could be construed as “disloyal.” It rounded up people in mass arrests, opened mail, and wiretapped phones (but failed to find any spies).

During this time, the Bureau also teamed up with the American Protective League, a group of vigilante thugs set up by a Chicago advertising executive and funded by various corporations. The APL spied on people (usually recent immigrants), sought out draft-evaders, busted unions, carried out break-ins, and beat up workers. They did all this while wearing badges declaring themselves an “auxiliary to the US Department of Justice.”

Aided by the APL — and cheered on by the New York Times — the Bureau carried out a twenty-four-city raid on IWW headquarters on September 17, 1917. They kicked down the IWW’s office doors, pilfered its documents, and in the subsequent mass trials, secured the convictions of 165 union leaders under the Espionage Act. Some received jail sentences of as long as twenty years.

A year later, they teamed up again for the “slacker raids,” arresting between fifty thousand and sixty-five thousand men across New York and New Jersey, the vast majority of whom weren’t even deserters or draft-dodgers. (The ensuing controversy prompted the dismissals of the attorney general and the Bureau’s chief, but the FBI as an institution survived unscathed.)

While the war ended in 1919, the Bureau’s political repression continued. It was front and center for the first Red Scare in the early 1920s, which was set off by a combination of labor unrest (including a general strike in Seattle) and a series of thirty-six bombings that targeted congressmen, mayors, judges, the secretary of labor, and the attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer.

The hysteria culminated in the 1920 Palmer Raids, overseen by a young J. Edgar Hoover, head of the Bureau’s General Intelligence Division. Hoover pored over the information gathered by the Bureau to determine who was most likely responsible for the bombings. The raids resulted in the arrest of six thousand people across thirty-three cities. More than one thousand of those were immigrants, hundreds of whom were deported (then–Secretary of Labor Lois Post reversed most of the original deportation orders). Those arrested, of course, had nothing to do with the bombing — their only crimes were things like opposing the war, agitating for better working conditions, and speaking with a foreign accent.

The Palmer Raids were so aggressive that they ended up turning opinion against the government’s actions. Palmer, who had initiated the raids partly out of his desperation to be president, tarnished his public standing — particularly when he predicted a revolution on May 1, 1920 that never ended up happening. (He had been informed by Hoover and the Bureau that it was indeed in the cards.)

“The ‘Palmer Raids’ were certainly not a bright spot for the young Bureau,” the FBI’s website now reads, in one of history’s great understatements. “But it did gain valuable experience in terrorism investigations and intelligence work and learn important lessons about the need to protect civil liberties and constitutional rights.”

The lessons the FBI learned are unclear. Its appetite for order certainly hadn’t been satiated by the Palmer Raids.

Fearful of unrest among black Americans, it began spying on and harassing African-American newspapers and civil rights groups like the NAACP. It was particularly worried about black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey, whose Universal Negro Improvement Association had 2 million members. Garvey was “one of the most prominent negro agitators in New York” according to Hoover. “Unfortunately,” he wrote in 1919, “he has not as yet violated any federal law whereby he could be proceeded against on the grounds of being an undesirable alien, from the point of view of deportation.”

The Bureau was so determined to take down Garvey, it did the unthinkable — it hired its first black agent, to infiltrate Garvey’s organization and get close to him. “[The Bureau] feared the hundreds of thousands, the masses of blacks under his influence,” writes historian Thomas Kornweibel. It ended up finally nailing Garvey on mail fraud and winning his deportation.

The Bureau also spied on Jane Addams, a progressive social worker and the leader of the Women’s International League for Freedom, an antiwar group. The League and its affiliates would continue to be monitored until at least 1942.

During the Teapot Dome scandal of 1923–24, the FBI reached its tentacles into the US Senate. Attorney General Harry Daugherty instructed FBI director William Burns to send Bureau agents to dig up damaging information about the two Montana senators spearheading the corruption investigation. Agents tapped the senators’ phones, read their mail, broke into their offices and homes, and at one point even tried to manufacture a compromising situation with one of the senators and a woman. The information Bureau agents obtained was then used to pursue, unsuccessfully, an indictment of one of the senators (at which point the whole scheme unravelled and Daugherty and Burns were dismissed).

All of this occurred within the Bureau’s first sixteen years — and before Hoover had even become the director.

Bad Old Days?

Hoover’s accession to the director’s seat marked the start of the FBI’s most notorious period, when the Bureau — backed up by the voluminous files Hoover kept on political friends and enemies alike — became a virtual second government unto itself.

The Bureau continued to keep tabs on anyone it considered outside the political mainstream: peace activists, civil rights groups like the NAACP, labor organizers, “suspicious minorities,” and the Left more generally. Hoover surveilled potential subversives, then handed information over to congressmen investigating “communist infiltration.” The Bureau kept an eye on folk singers for more than twenty years, including Pete Seeger, who it became particularly interested in after a line in one of his songs declared: “The FBI is worried. The bosses there are scared.” It also rifled through Albert Einstein’s trash and surveilled him until his death in 1955, spooked by such red flags as his pacifism, antiracism, and support for Spanish antifascism.

During this era, the Bureau again ventured outside the world of the Left and began investigating officeholders. Ordered by President Roosevelt to start surveilling potential subversives linked to the Soviets and Nazis, Hoover went further and began spying on those who crossed Roosevelt on foreign policy: Charles Lindbergh, the isolationist America First Committee, and four congressmen. It wasn’t the last time the FBI would be mobilized against a president’s political enemies: Lyndon Johnson had the FBI bug both Barry Goldwater’s and Richard Nixon’s planes in 1964 and 1968, respectively.

In 1956, the FBI launched the embodiment of its Bad Old Days: COINTELPRO, a set of programs that for decades essentially existed to destroy groups on the broad left, from socialist and communist groups to civil rights activists to the Black Panthers. Here were some of COINTELPRO’s greatest hits:

- Launching a campaign of anonymous letters that led one leader of the Puerto Rican independence movement to have a heart attack, which the Bureau celebrated.

- Attempting to incite violence against the Communist Party and the Black Panthers.

- Planting false gossip about the actress Jean Seberg, who had donated to the Black Panthers, which pushed her into a suicidal spiral that took her life in 1979.

- Attempting to blackmail Martin Luther King into committing suicide.

- Facilitating the Chicago police’s assassination of Fred Hampton, the chairman of the Chicago Black Panther Party.

- Paying provocateurs to infiltrate student protesters and plan and advocate bombings and murders, right down to providing the students weapons, training, and equipment to carry out the attacks.

- Hobbling the American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s through a barrage of baseless criminal accusations.

When such activities were exposed by the Church Committee in the 1970s, it scandalized the public. But the Bureau was unrepentant. As Hoover’s successor told Congress in 1971: “For the FBI to have done less under the circumstances would have been an abdication of its responsibilities to the American people.”

By Any Other Name

According to the conventional narrative, the FBI cleaned up its act once Hoover died and the Church Committee exposed its excesses. But the FBI has never entirely abandoned its original mission: to root out and surveil those whose political opinions veer from the Bureau’s own narrow orthodoxy.

You might know Edward Said as the man who coined the concept of “Orientalism.” For the Bureau, Said’s work with Palestinian organizations meant he was a security threat who needed to be spied on for three decades. It was neither the first or last time the Bureau would target pro-Palestinian activists.

Other organizations the FBI saw fit to monitor during the 1980s include: the Livermore Action group, various AIDS advocacy and gay rights groups like ACT UP and the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights, and the Committee in Solidarity With the People of El Salvador, a group opposed to the US’s Central American policy. One freelance journalist was detained by an FBI agent at an airport when returning from Nicaragua, at which point an FBI agent photocopied all of his papers.

Over the last two decades, the Bureau has mostly concerned itself with investigating antiwar activists. Since 2000, the FBI has spied on the Thomas Merton Center, the Catholic Worker, an individual Quaker peace activist, the Olympia Movement for Justice and Peace, Iraq Veterans Against the War, Food Not Bombs, and their old friends the IWW, among many others. In 2008, it raided the homes of six activists from the Freedom Road Socialist Organization and the offices of the Anti-War Committee, and spied on the libertarian website Antiwar.com.

Lest you think that only protesting war can attract FBI scrutiny, rest assured that in recent years the Bureau has also infiltrated and spied on Keystone XL protesters and helped coordinate the crackdown on Occupy Wall Street.

The Bureau’s treatment of Muslims deserves special singling out. During the Bush years, the FBI helped spy on five prominent Muslim Americans, one of whom (Agha Saeed) had endorsed Bush for president, and another (Nihad Awad) of whom had met with Bush before he delivered the “Islam is peace” speech many have spent the last few years gushing over.

Until recently, the FBI’s internal documents were rife with Islamophobia. In 2011, Wired reported that FBI counterterrorism agents were being taught that “mainstream Muslims” were terrorist sympathizers, that the more devout they were the more likely they were to be violent, and that Muslim Americans were essentially a population of terrorists ready at a moment’s notice to spring into action. The revelations prompted an internal purge of hundreds of documents, but as recent actions by Bureau agents have shown, it takes a lot more than eliminating such documents to change this mindset.

All of this is on top of the FBI’s most high-profile anti-terrorism work, which has mirrored its COINTELPRO-era use of paid provocateurs to incite violence and entrap protesters. While the Bureau (including Comey) often congratulates itself for preventing terrorist plots, many of these plots are ones wholly manufactured by the FBI, where agents or handsomely paid informants (who receive as much as $100,000 per assignment) give the would-be terrorists the idea for an attack, provide them with the money and contacts to buy the necessary weapons and equipment, and goad the reluctant attackers into carrying it out every step of the way.

According to Mother Jones’ Trevor Aaronson, all but three of the high-profile domestic terror plots in the ten years after September 2001 were FBI stings. In 2012, the FBI arrested five hapless Occupy protesters in Cleveland over a plot to blow up a bridge — one that was entirely conceived of and orchestrated by an FBI informant.

The FBI is not and never has been an apolitical guardian of democracy. From its very inception, it has been an agency that mixed the responsibility of serving as a national police detective force with the relentless — and highly political — task of going after movements that seek to challenge political orthodoxy, no matter how minor.

The FBI may not be committing COINTELPRO-like abuses anymore — at least not to our knowledge — but the Bureau’s recent history shows its authoritarian tendencies have never really gone away. Just because it happens to have crossed Trump does not mean it is worth of veneration. James Comey is not an American hero.

None of this is to say that the Bureau’s investigation of the Trump campaign is all smoke and mirrors, or that we shouldn’t be disturbed by the Comey firing. Trump’s bumbling attempt to potentially shield his administration from investigation is a serious matter. We should all be outraged at his blatant arrogation of power — but let’s not give the Bureau too much credit.