Survivor Has Become a Bleak Mirror of Modern Capitalism

When Survivor debuted in 2000, its appeal stemmed from the tension of clashing values, with some contestants taking a nakedly transactional approach and others appealing to the common good. In recent years, market logics have won.

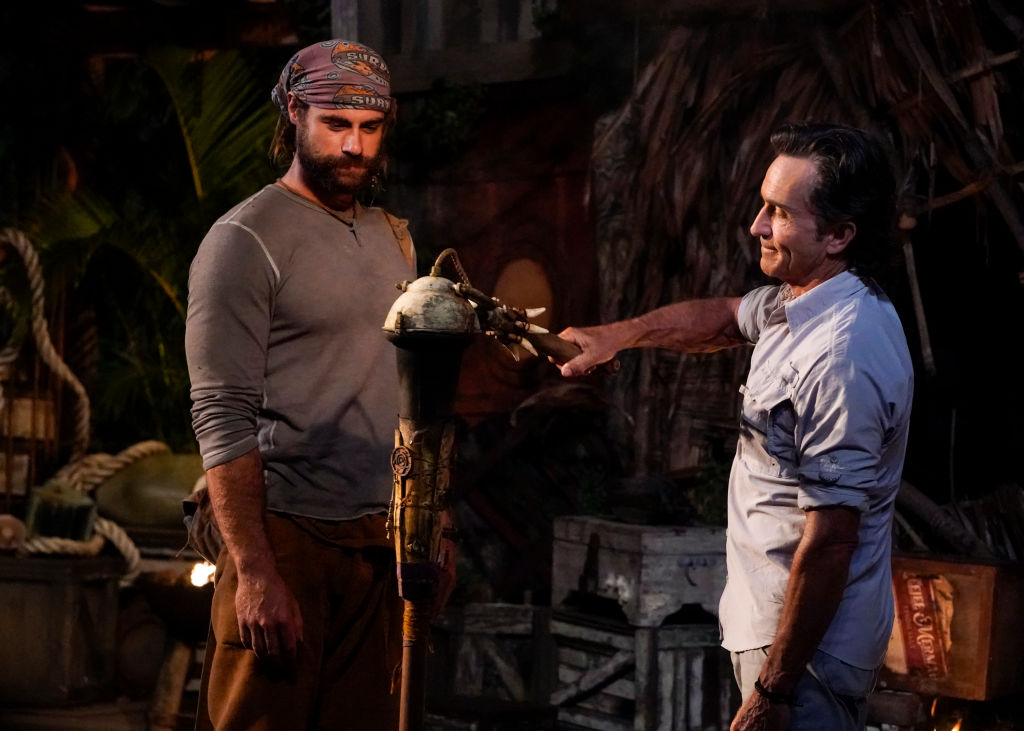

In the newer seasons of Survivor, contestants must build out their résumés, rapidly accumulate assets, and tolerate speculative risk. No wonder the show is losing viewers. We deal with capitalism every day and don’t need a simulation. (Robert Voets / CBS via Getty Images)

For twenty-six years, CBS’s Survivor has positioned itself as a grand experiment in traditional American meritocracy. Any individual who was smart, hardworking, and resilient enough could win the day. But in recent years, the game has evolved into something far more unjust. Indeed, Survivor has become a simulation of the economic system we experience every day.

The fundamental premise of Survivor has remained consistent since the turn of the millennium. A group of sixteen to twenty-four castaways is dropped into a remote tropical location where they must endure the elements, navigate physically and mentally demanding challenges, and face elimination at the hands of their peers. Each episode culminates at “Tribal Council,” an open-air forum where host Jeff Probst interrogates the tribe’s dynamics before the players cast secret ballots to evict one of their own. The final two or three remaining players make their case to a jury composed of previously eliminated players. These jurors vote not on who survived the longest, but on who best navigated the game’s social and strategic hurdles, awarding the winner the title of “Sole Survivor” and a $1 million prize.

When Survivor began filming its first season in the spring of 2000, the participants were unsure if they were in a hardcore adventure documentary or The Real World set in the jungle. Whatever it was, the American public was hooked: 51.7 million people tuned in for the finale to watch thirty-nine-year-old corporate consultant Richard Hatch defeat twenty-two-year-old river guide Kelly Wiglesworth. A cultural phenomenon that would redefine reality television was born. Throughout the show’s early years, Survivor’s cast was a genuine cross section of the country. Players fell in love, suffered medical evacuations, and launched careers in entertainment and media. They failed and triumphed, bonded and betrayed, and did it all with authentic, relatable, messy human emotion.

Today, Survivor endures, but its dominance over reality TV and its place in the cultural zeitgeist have greatly diminished. It has been outflanked by competitions with more pageantry, like The Traitors, and reality dating experiments like Love Is Blind. Its viewership has precipitously declined amid the broader fragmentation of the streaming era. As the show approaches its fiftieth season with Survivor 50: In the Hands of the Fans, it remains a network staple with a massive pop cultural legacy — but even the most loyal “superfans” will tell you that, despite the fundamental rules remaining intact, the game feels broken.

Fans offer various diagnoses: the show has gone “soft” in its pursuit of player safety; it has become too chaotic with a dizzying proliferation of advantages and side quests; it is too centered on Jeff Probst’s own brand of relentless positivity. But most share a common sentiment: Survivor has lost its way because it no longer creates and showcases the honest, crackling social friction that made it a cultural juggernaut a quarter century ago.

In this analysis, the show’s decline isn’t a failure of casting or game design, but a symptom of a deeper transformation. The “social contract” gameplay of the early seasons has been replaced by the “market logic” of the show’s so-called New Era — a shift that maps onto the successful neoliberal disciplining of the American public and the erosion of the American social fabric.

All That Is Solid Melts Into Air

To be clear, ruthless market logic was there from the start. But Survivor’s core appeal stemmed from the tension created by clashing values, with some taking a nakedly transactional approach and others appealing to the common good. The problem today isn’t that there are canny marketized actors in the mix; it’s that there are few alternatives. Approaching the game like a “business trip” has become de rigueur, dissolving the conflicts that made the show sizzle.

After the first season aired in 2000, Richard Hatch became a national villain for treating human relationships as transactional assets. The public approached the first season as a social experiment: could strangers build a functional society in the wilderness? Viewers expected a meritocracy where players were rewarded for their contributions to the common good: building shelters, making fires, and winning challenges. The castaways assumed much the same. With little direction from producers, they operated under the assumption of a “social contract.” They believed their votes were private, moral acts intended to prune the tribe of its weakest members for the sake of collective survival.

But Hatch realized that individual moral voting was inefficient. Early in the game, Hatch formed an alliance (the Tagi Four) with Wiglesworth, Sue Hawk, and Rudy Boesch, who all agreed to vote for the same person at Tribal Councils. By pooling votes to maximize the value of a collective asset, Hatch introduced a market logic that overrode the democratic intent of the other players. The goal was no longer to sustain the tribe, but to liquidate the competition. In subsequent seasons, this approach would frequently appear and clash with warmer, more moral approaches.

A few years later, Rob Cesternino introduced a new element when he pioneered the flip-flopping strategy in Survivor: The Amazon (2003). Finding himself at the bottom of a dominant four-person alliance, Cesternino’s ally, Alex Bell, bluntly told him that he would be cut as soon as they reached the final four. Realizing he had no “upward mobility” within his current alliance, Cesternino rejected his position: he mobilized outsiders to eliminate Bell, then flipped back to the original power players, and then back again — maintaining a state of constant strategic volatility until he reached the final three. This strategy and later adaptations were quickly adopted by players who found themselves “at the bottom” of their alliance, their only rational move being to jump ship and improve their equity in the game.

To understand what precise dynamic Cesternino introduced, imagine a professional who uses the strategy of “job hopping” to continually raise their pay. Cesternino’s gameplay mirrors the rise of external labor mobility as a primary form of career development. Just as professional-managerial workers realize that stagnant internal meritocracies and meager annual raises cannot fetch the market rate for their skills, Cesternino realized the only path to a market correction (a spot in the final two) was to pivot to the competition.

In the real world, older generations of workers from the era of the “company man” look down on job hopping as a form of betrayal and lack of commitment. But the astute worker realizes that the social contract between employer and employee has been in slow decay since Milton Friedman’s shareholder primacy doctrine took root in the late 1970s, which led corporations to prioritize quarterly profits over long-term employee retention. By the 2020s, strategic flip-flopping had become the standard mode of survival for the professional-managerial class. That’s precisely what happened on the show. On Survivor, as in the modern economy, blind loyalty had become a bad investment.

While shelter building, fire making, and fishing remained staples of the show’s early years, communal labor was gradually devalued as a new class of assets entered the game. The advantage that came to define modern gameplay is the Hidden Immunity Idol, a pocket-sized talisman that allows players to negate votes at Tribal Council. In Survivor: Cook Islands (2006), Yul Kwon — a thirty-one-year-old management consultant — found a “Super Idol,” a version of the idol that could be played after the votes were read. Kwon leveraged the idol’s outsize value in alliance negotiations; despite his alliance’s numerical disadvantage, he used the asset as a credible threat to force votes in his alliance’s favor.

Kwon held onto the idol until the endgame and won over Ozzy Lusth, a twenty-four-year-old waiter. It was the first time a player won by expertly managing a high-value asset. A few seasons later, the infamous Russell Hantz would take idol leverage to its logical conclusion in Survivor: Samoa (2009). Hantz, an oil company owner from Texas, approached gameplay like a scavenger hunt for hidden assets: he was the first player to spend every waking hour hunting for idols, effectively controlling the supply.

While Hantz lost in back-to-back seasons due to his dismal social game, he fundamentally changed the game’s incentive structure. The ability to manipulate these assets is a prerequisite for the title of Sole Survivor. The introduction of idols financialized the island, shifting Survivor from a productive society — where safety was earned through communal labor — to an asset-price economy, where power is hoarded by those who capture the supply of advantages.

Cold Strategy and Private Advantages

Despite the fact that players applied efficiency, flexibility, and scarcity — trademarks of the neoliberal era — to their strategies from the start, the drama of Survivor came from the continued presence of players who believed the social contract meant something.

For years, a fundamental belief persisted: that fan favorites like Colby Donaldson and Rupert Boneham could win through integrity, communal labor, and “honor,” even as players like Hantz and Cesternino dismantled the game’s social contract from within. Occasionally, this belief was validated by a figure like Tom Westman, a forty-year-old New York City firefighter who defeated twenty-nine-year-old advertising executive Katie Gallagher in Survivor: Palau (2005).

But as the New Era (seasons 41–49) indicates, the social experiment is over — the market has finally won. With the proliferation of game assets, hyper-fixation on “résumés,” and the disappearance of working-class players, the takeover of neoliberal discipline was complete. The first winner of this era, Erika Casupanan, a thirty-two-year-old communications manager, applied corporate public relations principles to her gameplay, managing her reputation and lowering her threat level until the conditions were right to strike. The following season, Maryanne Oketch, a twenty-four-year-old seminary student, won by revealing a hidden asset — an idol she never actually used — and updating her résumé for the jury.

The majority of winners in this stretch of seasons are from white-collar backgrounds. While a CBS initiative in 2020 successfully changed Survivor’s racial makeup, the class makeup has narrowed. As the show returned from its 2020 production hiatus, the casting department shifted away from a cross section of the American workforce and toward a credentialed class of players. The game is now populated by data analysts, law students, and entrepreneurs — individuals whose professional lives are defined by the very market logic Hatch once pioneered. In the modern game, there is no rejection of corporate values because there is no one left to represent an alternative.

The theorist Mark Fisher used the term “capitalist realism” to describe the widespread inability to imagine any social or economic system other than capitalism. Fisher argued that this lack of imagination eventually warps our politics and public sentiment. In Survivor, this manifests as a totalizing belief that the only path to victory is through cold strategy and the relentless pursuit of private advantages. To keep the competitive market high, producers began casting highly trained professionals who view social connections as mere data points. Fans have dubbed these players “gamebots,” participants who prioritize strategic optimization, including in the social realm, over authentic human connection.

As seasons became predictable and stagnant, the producers attempted to nerf the game’s efficiency by introducing new twists, advantages, and side quests: Extra Votes, Safety Without Power, Final-Four Firemaking, Shot in the Dark, Beware Advantage, Knowledge is Power, the Hourglass, “Mergatory.” These are the Survivor equivalents of fifty-year mortgages, buy-now-pay-later apps, or text-based therapy subscriptions: absurd financial “innovations” designed to mask the rot of the underlying system.

The players who find success in the New Era can’t be blamed for utilizing the tools at their disposal. Any contestant trying to earnestly win the $1 million prize is expected to negotiate positions within alliances, build out a résumé, rapidly accumulate assets, and tolerate speculative risk as if they are playing in an overengineered simulation of late-stage capitalism — because they are.

But considering how thoroughly neoliberal values have seeped into the game, it’s little wonder why viewers don’t enjoy watching the show as much as the early seasons. It just reminds them of their twenty-first century workplace, and how the survival experiment they once loved has turned into an HR-sanctioned team-building retreat.