Cem Kaya and the Politics of Migration

Today deportations and restricted asylum rights are changing the terms of political belonging around the world. With surreal and darkly humorous archival works, German filmmaker Cem Kaya is exploring how anti-migrant racism is mediated through capitalism.

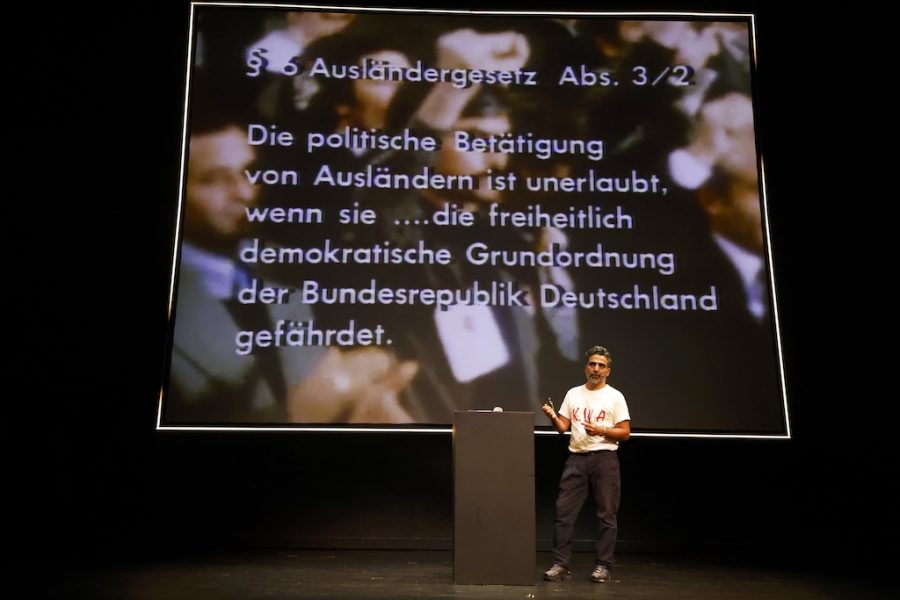

Ekim Zafer Acun (ŞOKOPOP) in Cem Kaya’s Pop, Pein, Paragraphen. (Ute Langkafel / Galerie MAIFOTO / cropped)

On August 30, 1983, Cemal Kemal Altun threw himself from the sixth floor of the Berlin Higher Administrative Court during the second day of legal proceedings assessing his request for political asylum in West Germany. He was twenty-three years old. Seeking asylum following the 1980 military coup in Turkey and his involvement in left-wing student politics, Altun had initially been granted protection before the German Ministry of the Interior chose to inform the Turkish military, who wanted his arrest on false charges, of his presence in the country — a decision that was part of Germany’s wider support for the Turkish military government’s crackdown on leftist and Kurdish movements. Taken into custody pending extradition, Altun was kept in solitary confinement for thirteen months and had information withheld from him about his chances of maintaining asylum status (chances that were later declared to be high). Video footage of the legal proceedings shows him looking calm and watchful. The camera was still rolling when he jumped out the window.

Forty years later, Western political landscapes continue to be fractured and reconfigured around the politics of asylum and deportations, which are producing distinctive relations with far-right and authoritarian forms of power in new guises. In Germany, the government is reshaping its asylum policies with tougher rules. In the UK, the Home Secretary has announced the biggest overhaul of the migration model in the past fifty years, aimed at increasing the number of deportations. In the United States, Donald Trump is fulfilling his promise to enforce the “largest deportation operation in American history,” deporting over six hundred thousand people in his first year in office and stripping legal status from a further 1.6 million individuals.

Meanwhile, Turkey continues to serve as a destination for deported individuals from Europe, specifically under the terms of the 2016 EU-Turkey Deal, an agreement through which irregular migrants would be returned from Greece to Turkey. Turkey is also actively removing hundreds of thousands of mostly Syrian and Afghan refugees as part of the reported “EU-funded deportation machine” and its own political agendas. Deportations are a form of class strategy — their threat works to suppress labor standards and wages, produces fragmentation and division in the workplace, and maintains a labor force that is always potentially “illegalized” and thus disposable. But they are also highly political instruments of incarceration that work across interconnected geographical landscapes.

The filmmaker Cem Kaya locates his work in this entangled terrain, tracing the history and politics that have produced tightening asylum policies and heightened anti-migrant racism in Germany. Born in Bavaria in 1976, Kaya’s archival video work pays attention to power. In his most recent piece, the video lecture Pop, Pein, Paragraphen [Pop, Pain, Paragraphs], which he performs at the Maxim Gorki Theater in Berlin, he interweaves Cemal Kemal Altun’s 1983 legal case with the fabric of local, national (German and Turkish), and geopolitical politics. Kaya traces the arc of West German asylum policies, particularly how these emerged out of the madness and alienation of the 1980s and ’90s, periods marked by shifting relationships with nationalism and capitalism in the context of Cold War politics. The volatility is captured through archives of pop culture, protests, and speeches — a bricolage of music, photographs, cultural memorabilia, and the electric volt of politics that charges through it. Kaya delights in the kitsch, the surreal, and the darkly humorous.

His engagement is broader than just a narrow critique of Germany’s legal history. He’s concerned with the subjects of political belonging, nationalism, and cultural community — and how these emerge through and are mediated by capitalism. More specifically, he traces the tight connections that underpin the supposedly opposite systems of European liberal democracy and Turkey’s authoritarian government. Migration, asylum, and deportation policies, with all their messy human entrails, clarify the stakes of these entanglements. In Kaya’s account, the political horizons of German asylum laws are cramped or expanded in relation to the tumult produced by different forms of consumption — of capital, nostalgia, nationalism, migrant labor, security. He inquires into what the politics of migration tells us about the entrenched collaboration of liberalism and authoritarianism across political structures, and the grainy workings of power.

The Entangled Recent History of Germany and Turkey

Pop, Pein, Paragraphen opens with a surreal montage of images of the language classes of smartly dressed Turkish “Gastarbeiter,” or guest workers, who were recruited to close gaps in the German labor market starting in the early 1960s. An official German language video from 1967 shows a foreign woman being kidnapped by bandits in a country estate before encountering statues of Ludwig van Beethoven, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Alexander von Humboldt, who spring to life and cheerfully test her on her German language skills. “This isn’t a dream,” they tell her. “You’re really here.”

From this myth-like confrontation with classical figures of German history we move, via footage of contemporary border policing, boats, barbed wire, bodies, politicians, and factories, to a detailed account of Cemal Kemal Altun’s case. News reports, video footage, and interviews with Altun’s lawyer provide the details. Altun’s case should have been decided in a single day, we learn. The reason for the second day of proceedings — the day his death occurred — was the presence of an “uncertified” translator. This detail is not inconsequential; the workings of politics itself is to be found in such dry, bureaucratic routines. The case came in the context of heightened political agitation against “non-Germans” and discussions of integration that defined the 1980s. Altun’s death brought eight thousand mourners to the streets of West Berlin to protest West Germany’s unjust asylum system.

Kaya turns to Ekim Zafer Acun, professionally known as Şokopop, to situate Altun’s case in a wider context of German-Turkish relations in the 1980s. A YouTuber from Istanbul who has gained a mass following for online excavations of the “deepest tabloid pits,” Şokopop makes political interventions out of the detritus of pop culture. The ’80s brought the arrival of video technology alongside a fully marketized society to Turkey. Turgut Özal’s right-wing Motherland Party government fully embraced neoliberal ideology, with all its “flaws and perversions” — trying, and failing, to synthesize the disparate ideologies of social democracy, liberalism, nationalism, and religious conservatism alongside stifling political opposition. Şokopop is attuned to the weird debasements of this muscular and affective politics, which prized celebrity, indulgence, and vapid growth. This was an era when individualism reigned and rules lost meaning — particularly for the financial regulation and mass construction projects that accelerated the rapacious industrialization of Turkey. A bizarre collection of footage from 1980s Turkey shows the confluence of tabloids, glitter, computers, and motorways, as well as the influence of the widely popular American sitcoms Dynasty (banned from state broadcasting due to the presence of a gay character) and Dallas.

During this decade, West German and Turkish relations, already deeply embedded economically, militarily, and politically, took on further strategic and security cooperation, particularly in the guise of anti-communist alliance. This cooperation built on a long history of exchange of knowledge, infrastructure, policing, and security mechanisms as well as various forms of reciprocal migration. The signifiers of pop culture tease out these entanglements. The montage of archival footage positions the fragile construction of national identity of both countries within the contours of mass consumption and the flows of capital. The fault lines of political momentum are not clearly defined — we are invited to look at the volatile cultural and material debris that mark their parameters.

Recentering the Migrant

Cem Kaya stages a confrontation with the practices of politics and history, in which the figure of the migrant is the true motivating force. In his 2022 documentary Love, Deutschmarks and Death, Kaya foregrounds the ways that the Turkish community in Germany navigated commonality and difference through music, which they produced and consumed as a direct response to their harsh migrant condition. Similar to Ralph Ellison’s descriptions of jazz, in which “there is a cruel contradiction implicit in the art form itself,” the music of different generations of Turkish émigrés, from the guest workers in the 1960s onward, gave voice to fragile forms of belonging produced out of the alienation between distinct worlds. Sharing music, collectively experienced as something triumphant, in the words of John Berger, was key to this sense of community building between spaces.

Kaya’s footage in Love, Deutschmarks and Death is a more intimate engagement with the Turkish-speaking experience across Germany. Singers from this period voiced the disorientation, homesickness, and alienation of the first arrivals. We see the cramped and moldy living conditions they experienced in the 1970s, when the guest worker agreement officially ended and workers who had given Germany their life and labor were expected to return to Turkey.

Instead they were housed in intolerable conditions, with few workplace rights and overt discrimination. Interviews with teenagers hint at the obstacles they faced attending school: “We will most probably also end up as unskilled workers,” as one young woman, part of the so-called lost generation who had no legal rights in the country, bluntly puts it. We hear about the Turkish bazaar set up in the disused Bülowstraße U-Bahn station in West Berlin in the ’80s, which housed kebab joints, wedding shops, and cassette markets and transformed every night into a cabaret of music and dance. Anti-Turkish and Kurdish racial violence, including arson, bombings, and shootings, also emerged in this decade, escalating after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The music that materialized in the 1990s in response to this racism reflected the anger and political consciousness of a new generation that wanted to assert its right to live in Germany. “Piss off skinhead, get out of my sight,” sang Alper Ağa of Cartel, the first Turkish-language rap group to achieve nationwide recognition, which channeled the rage of this moment.

Today’s Deportation Policies

Kaya’s oeuvre helps capture the interconnected terrains through which anti-migrant racism is emerging today, in which there is an internationalization of an effectively global regime of deportation. Pop, Pein, Paragraphen takes a more systemic approach to migration practices, examining West German asylum regulations and situating them across national borders. Asylum policies here were tied to a mesh of different agendas, not only strong economic ties but the security cooperation that led Germany to help repress leftist and Kurdish political struggles taking place at the time in Turkey. Love, Deutschmarks and Death focuses on the stories, anecdotes, and melodies that constructed the relationship between Turks and their sociocultural space in Germany and beyond. For the cultural theorist Stuart Hall, there is nothing reductive or predictable about the dance between the intimate and the broader structures of power. It is in the tensions and frictions between them that politics emerges.

Kaya’s attention to the tightly intertwined relationship between Germany and Turkey provides several crucial insights into broader debates about migration policies. The first is a reminder that migration politics are not only the purview of narrow national concerns but reflective of wider interconnected geopolitics. Mapping the entangled landscape, from the intimacy of the home to the harsh bureaucracy of migration decisions and the halls of government from which they emerge, gives a hint of the scale. The second is how contemporary asylum policies are reworking historical relationships — not repeating but reconfiguring them.

Today, deportations, restricted asylum rights, and the stripping of legal protection are tightening the terms of political belonging along ever more squeezed parameters of nationalism in various countries, including Germany, Turkey, the UK, and the United States. This is happening alongside the flexing of naked imperialist ambitions, from Trump’s oil grab in Venezuela to Turkey’s intervention in northern Syria. Historicizing these shifting connections between nationalism, capitalism, and forms of imperialist power gives a clearer sense of their stakes and implications. Starting from the struggles of the migrant provides a more focused lens for analyzing the power structures converging at these moments, touched by overlapping agendas, actors, and techniques.

Through Kaya’s archival arrangements, the close relationship between Turkey and Germany is brought more clearly into view, tied together through not only economics, trade, and political diplomacy but asylum policies. As Cem Kaya notes at the end of his Pop, Pein, Paragraphen lecture, these historical asylum policies included Germany’s granting of protection in 1918 to Talaat Pasha — the de facto leader of the Ottoman Empire who is widely considered one of three architects of the Armenian genocide. Pasha was assassinated by gunshot in Berlin in 1921 by Soghomon Tehlirian, a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. The location of his shooting lies a few hundred meters from the administrative court where Cemal Kemal Altun committed suicide. Kaya poignantly asks how we should understand the connected fate of these two men, one a convicted war criminal and the other a young leftist student, who were treated so differently by distinct German governments.