Cover-Up Follows Seymour Hersh’s Life Uncovering Secrets

Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’s Netflix documentary Cover-Up follows the life and work of legendary investigative reporter Seymour Hersh. Cover-Up depicts the kind of maverick journalism we desperately need in our authoritarian times.

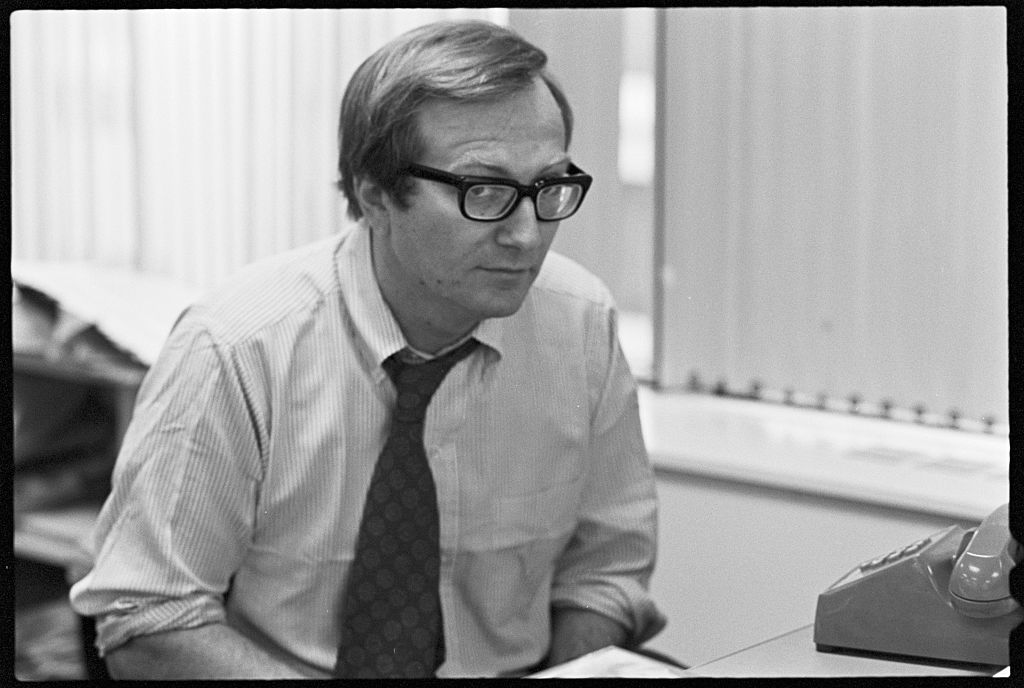

“A theme throughout the film is obviously government abuse of power. But also the failure of the legacy media to do its job.” — Laura Poitras on Cover-Up, her new documentary about legendary investigative journalist Seymour Hersh. (Diana Walker / The Chronicle Collection / Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Ed Rampell

As the Trump regime swings a wrecking ball at the news media, codirectors Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus have created a master class in investigative reporting. Their new documentary Cover-Up, which premieres on Netflix on December 26, chronicles the earth-shaking reportage by eighty-eight-year-old Seymour Hersh, who began his journalistic career as a humble copyboy at Chicago’s City News Bureau and went on to out-scoop his way to earn a Pulitzer Prize, five George Polk Awards, and other accolades.

The muckraking Hersh has exposed some of America’s worst scandals, as well as the corporate press, and in their almost two-hour documentary two cinematic sleuths paint a compelling picture of one of our most prominent truthtellers.

Obenhaus has co-won three Emmy Awards, while codirector Laura Poitras’ Citizenfour (2014), about NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, earned the Best Documentary Academy Award, a Polk Award, and a Pulitzer Prize for Public Service that Poitras shared with the Washington Post and the Guardian. Poitras’ My Country, My Country (2006)and All the Beauty and the Bloodshed (2022) were also nominated for Best Documentary Oscars. In addition to winning an International Documentary Association award for Feature Documentaries, Cover-Up has been shortlisted for 2026’s Best Documentary Oscar and has been a favorite on the film festival circuit, receiving awards and nominations.

Jacobin interviewed Poitras via Zoom at her New York office. This interview has been edited for clarity.

What attracted you to make a film about Seymour Hersh?

Seymour Hersh is a legend of investigative journalism. He has been for the last half century breaking some of the most important stories, exposing American atrocities, government lies, cover-ups, coup attempts, assassination attempts. The list is really long. He’s been somebody who has inspired my work for as long as I’ve been doing documentary filmmaking.

This has been a project that I originally approached Sy about twenty years ago. I just said, “Come on, Sy, like let’s make the movie.” He was very gracious, very charming, very funny, and said, “No f-cking way.”

Let’s get into the nitty-gritty of the highlights that Cover-Up covers. Hersh’s first big national story was exposing the My Lai massacre. What did Hersh find out and how did he do it?

Sy cut his teeth as a journalist in Chicago at the City News Bureau and then got a job at the Associated Press (AP) in Chicago. Did Civil Rights reporting, which is very interesting. Then was assigned to the Pentagon in Washington, DC, which he sort of laughs about: “The Pentagon probably regrets that.” He quickly learned what the government was saying about the [Vietnam] war were lies. So, he became increasingly disillusioned, increasingly skeptical, and he also started working with people who were part of the antiwar movement.

He quite the AP, he actually briefly joined the antiwar campaign of [Senator] Eugene McCarthy, he was its spokesperson and press secretary for several months because it was a way to try to tell the public about what’s happening with this war. He was obsessed with it. He then quits Eugene and then was working freelance at an office down the hall from Ralph Nader, and he just gets a tip.

And the tip says there’s going to be a court-martial. There’s a soldier in the Army who’s going to get court-martialed. No name, no details, something about somebody shooting people up, but not really specifics. His instincts told him he needed to follow this story — and he did. He went to the Pentagon, talked to a general, got the name [Lieutenant William] Calley, then tracked down his lawyer [George W. Latimer]. Sy describes the lawyer taking out the charge sheet and he sees there’s a massacre of civilians.

Then Sy gets on a plane to try to find this guy, Calley. And tracks him down at Fort Benning. So, then he has the story. He knows there was a massacre; he knows the name of the soldier. Then he’s struggling to get it published. Which is shocking, right? You’d think that this is a big story, that everybody would want it. But he went to Life magazine and they said, “no thank you.” I think he went to the Washington Post, et cetera.

Then finally Sy approached David Obst, who was running a very small antiwar publication called Dispatch News and they syndicated it. Which means Sy wrote a story and then David Obst called every editor across the country and said, “We’ve got this story. Will you publish it?” Everybody paid $100 and the first story ran in thirty news organizations, the Boston Globe and others. So, that was the first drop.

Then, he was still obsessed, so he then finds [Vietnam veteran] Ron Ridenhour, a whistleblower, who had written to Congress about this massacre. Then there’s a second story. Then after the second or third story, Sy interviews [Vietnam veteran] Paul Meadlo, whose mother has this line: “I sent them a good boy and they sent me back a murderer.” Then Meadlo does an interview with Mike Wallace. The following day, the New York Times published a transcript of the interview.

What’s interesting about this story is it was over a year — the massacre happened in 1968, and Sy’s story broke in 1969. So, for over a year, it was being covered up by the government and by the journalists who — Sy believes very strongly — would have known about it. If you were on the Vietnam beat, you would have heard about this massacre.

Then we learn there’s a photographer — the Army sent a photographer. Which is what happens. Some of the worst crimes perpetrated by the state are often documented by the state. [Army combat photographer] Ron Haeberle starts to publish his photographs. Then it’s global news. It goes from this tip to being a global story.

For me, it’s a lesson about the importance of dogged investigative journalism, follow your instincts. Don’t say no when the powers that be tell you that there’s not a story there, that there’s nothing to publish, and just keep following the story. The My Lai massacre, ultimately what was revealed is that there were over five hundred innocent civilians, in a village, massacred by US Army soldiers.

And the context of it is that it was something that was ordered from higher up. That [the commander of US forces in Vietnam, General William] Westmoreland, who was running the war, and the generals, they wanted body counts. And that meant killing people — even if they were babies.

You commented upon the Pentagon ruing that Hersh had been assigned to cover it. Can you imagine Seymour Hersh under the rules that Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth has imposed upon reporters at the Pentagon now?

Sy jokes that they sent a Jewish lefty from Chicago to report on the Pentagon. It wasn’t a good idea. No, Sy would never sit in one of those rooms. From Sy’s perspective, Pentagon press briefings or White House press briefings are places where lies are disseminated, from government to journalists. It’s not where the journalism happens. He would never sign one of these oaths, and no journalist should.

But the bigger question is: Why do we have dozens of journalists writing down government lies, then publishing them in their news organizations? When we find out, over and over again, the truth, and the truth totally contradicts those lies. I’m thinking of Donald Rumsfeld, who you see in Cover-Up, lying through his teeth at a press conference about what he knew about the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison.

A theme throughout the film is obviously government abuse of power, atrocities, lies, cover-ups, all that kind of thing, across decades. But also the failure of the legacy media to do its job. To be critical of the wars when they are happening, when people are dying.

Breaking the Watergate story is usually attributed to Woodward and Bernstein. But what role did Hersh play in exposing the Watergate scandal?

It’s always attributed to Woodward and Bernstein, and should be. And Sy attributes it to them. As he says in Cover-Up, they own this story. They showed up, they were running with it. I think it was seven months between Woodward and Bernstein’s first reporting and then [editor] Abe Rosenthal of the [New York] Times finally saying, “We are getting destroyed. We’re getting creamed by the Washington Post on this story. We need to catch up.” And they assigned Sy to work on it. He didn’t want to for a lot of reasons. He was behind on the story by seven months. He didn’t have sources in the White House and the Justice Department. He didn’t want to take over somebody else’s story. And, he was working on the Vietnam War.

But, he did. Sy quickly developed sources. What Woodward says in the film, Sy’s first big story was that the Watergate burglars were still being paid for their silence [six months after the break in at Democratic National Committee headquarters]. Woodward says that really advanced the story. Both because it showed the extent, but it also, for the Washington Post, when you’re alone on a story for a really long time, it’s a lot of pressure on an organization. I mean, you’re going after the president of the United States. Woodward welcomed Sy and getting the New York Times in on the story.

He enjoyed the competition; it was a lot of fun. But still, Sy would be the first to say that Woodward and Bernstein deserve all the credit for breaking that story and bringing down Nixon.

Tell us about Hersh’s 1983 book The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House? What did Hersh reveal about Kissinger, in particular about the US role in the 1973 coup in Chile?

Sy goes from being this outsider, troublemaker, antiwar journalist who exposed My Lai, he gets a Pulitzer — the first independent journalist to ever win a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting. Then he gets hired by the Times. There’s an interview with his editor there, Bill Kovach, [who says] Sy changed the culture inside the New York Times. Kovach has a line that’s something like: “The Times didn’t want to be beat, but was terrified of a story that pushed back against government power.” They wanted both, they wanted the scoops, but they didn’t want to piss off the government.

Sy got to the Times and became obsessed with Henry Kissinger, because of what he was doing behind the scenes all over the world, on “the 40 Committee,” this shadowy organization of US officials who were supporting all kinds of dictators around the world or trying to undermine democratically elected leaders, including [Salvador] Allende in Chile.

Sy was obsessed with Kissinger always. He was in his crosshairs throughout his time at the New York Times. After he quits the New York Times, Sy decides to write this seven-hundred-page The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House. So, Kissinger really hated Sy Hersh and is consistently coming after him. The United States, as it does and continues to do, was supporting an opposition organization in Chile that were thugs and murderers, because they wanted to overthrow democratically elected President Allende. Ultimately, there was an assassination of a general, and ultimately, by supporting this antidemocratic, authoritarian group, there was a coup, Allende is killed, leading to [General Augusto] Pinochet’s reign of terror.

What was Hersh’s role in revealing what was happening at Abu Ghraib prison and how did he go about doing that?

Sy was at the New Yorker on 9/11. [Editor David] Remnick assigned him to be on the 9/11 beat. He did incredible reporting in the immediate aftermath of that. Trying to understand what went wrong, how did this happen? In the lead up to the Iraq War, Sy was totally against the invasion, pointing out this was really about Dick Cheney and Halliburton and making money and oil — and nothing to do with 9/11. There was no connection between Iraq and the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

The tip that Sy got is, after the invasion, in early 2004, he was meeting with a former general in the Iraqi army who starts telling him about Abu Ghraib prison. Saying that there are people being held there who are being tortured to death. Real nightmare stuff. So, he knew about it — but he didn’t have enough quite yet to publish it. Then he was contacted by somebody who worked for 60 Minutes, Roger Charles, who said: “60 Minutes has evidence of torture at Abu Ghraib but the US government is pressuring them not to broadcast it because it’s going to hurt the war effort.”

Which is, as a journalist, a scandal. Right? You have something of newsworthy value you go with it. Roger Charles reached out to Sy because he was worried that this story would be covered up and suppressed, and the world would never know that prisoners had been tortured at Abu Ghraib. So, Sy then contacted a lawyer, as he does — shoe leather journalism. He visited a lawyer who happened to be one of the lawyers from the My Lai case. And that lawyer says, “Yeah, of course, there’s this Taguba Report.” And he hands it to Sy.

And then Sy knows he has the biggest story on the planet. Because the report that was conducted by a two-star general in the US military, Antonio Taguba, basically says that US soldiers were illegally, sadistically torturing prisoners. And then Sy gets photographs — and they’re some of the most horrifying images ever revealed about what the US military was doing there.

Sy pressures 60 Minutes into broadcasting. He says: “Listen, I’m about to publish this. If you don’t broadcast, the second paragraph of my story is going to be, ‘60 Minutes is not fulfilling its obligations as a news organization.’” So, then 60 Minutes does [air its Abu Ghraib story], and Sy publishes his. It’s one of the most important stories about the Iraq War.

What makes Seymour Hersh tick? What is he covering up?

[Laughs.] You know, I don’t think — Sy’s kind of — what is he covering up? He’s protecting his sources, but I wouldn’t call that a cover-up. He doesn’t cover-up a lot, he’s a pretty open book. Always game to answer any question we asked. Even though you get in the film that he has some resistance to talking about his family, he’s very honest and principled to a fault. He really follows his moral compass, I guess.

This film is not a biopic. It’s a portrait of Sy — it’s a portrait of America through the lens of Sy’s reporting. But we do spend some time on him growing up. That’s a lot of what makes him tick. Being the son of immigrants who escaped Eastern Europe during the pogroms, but before World War II, when his whole extended family was wiped out. Total silence of the family.

He grew up in Chicago, not really feeling he had opportunities. Growing up, his dad had a business in a black community, he saw racism up close. He knows that he was lucky — somebody saw the potential in him and got him into the University of Chicago. All of his growing up, his feeling about injustice, fighting injustice, understanding how the real world really works, and also being allergic to lies and bullsh-t — that all feeds into everything he does. He’s just a classic antiauthoritarian. He’s a bit of a punk — he identifies as one.

Hersh is at an advanced age now. What is he working on nowadays?

Sy is at Substack. He has over two hundred thousand subscribers. He writes weekly. Right now, as the film shows, he’s writing about the genocide in Gaza; he’s horrified with what’s happening there. He’s writing about the Trump administration and his concerns for this country. He’s still very active, writing daily. Sy says that, “The day I don’t chase a story like that is the day that I’m dead.” I think he’s going to be doing this his whole life. This is what he does.

The reason I made Cover-Up is because I really think this country has to deal with its lies and its violence and to look at how there is a repeated pattern of wrongdoing, abuse of power, atrocity, followed by lies and cover-ups, and then impunity. With impunity, people aren’t held accountable, it sets the stage for it to happen over and over again. We begin with chemical and biological weapons and the Dugway incident, where 6,six thousand sheep are killed by nerve gas because the United States is experimenting with nerve agents to use in Vietnam [chronicled 1968 in Hersh’s first book, Chemical and Biological Warfare: America’s Hidden Arsenal]. Then the government lies and just that, repeating over and over, across administrations of both political parties. I think we need to interrogate that.

If this film does anything, I hope it makes the audience more skeptical of what they hear from the government and legacy news organizations. We should be critical. All we have to do is look at what’s happening with these extrajudicial assassinations of boats off Venezuela. When did we stop having any kind of due process? It’ll only lead to worse. If the United States thinks it can go around and kill anyone, anywhere on the planet, then we should assume other countries are going to start doing the same. I just don’t think that’s a world we want to be in.

How’s Edward Snowden doing nowadays?

I was just texting with him yesterday. He and his partner Lindsay have two kids, he has asylum. He would like very much to be in a different country; he’s in Moscow. His lawyers have been trying to get him into other European countries. The United States put enormous pressure on all of its European allies not to give him asylum. I think Germany would have wanted to, France. . . I hope he’ll be able to move somewhere else. I should also say that I’m glad he’s not in a US cell right now. He did a great public service.

[Cover-Up premieres December 26 on Netflix.]