The Dutch Left Had Its Worst Performance Ever

The Dutch elections were a victory for liberal centrists and a defeat for the anti-immigration Geert Wilders. Yet with the overall right-wing vote stronger than ever, there’s little reason for celebration.

The liberal-democratic Democrats 66, led by Rob Jetten, looks set to steer a pro-EU cabinet in the Netherlands. (Simon Wohlfahrt / AFP via Getty Images)

Read most liberal papers’ coverage of the October 29 elections in the Netherlands and you find this sort of headline: “Far Right Beaten, Dutch Good Sense Restored.” After two bruising years in office following an unprecedented electoral victory for Geert Wilders’s far-right Party for Freedom (PVV) in 2023, the experiment of a PVV-led government collapsed. This time, neat technocrats from the liberal-democratic Democrats 66 (D66) look set to steer a pro-EU cabinet. It sounds like a return to steady hands.

But on closer inspection, that is hardly the whole tale — especially for anyone on the Left. Three numbers should make us pause.

First, after the October 29 vote, the core trio of far-right parties — PVV, JA21 (Conservative Liberals), and Forum for Democracy — hold forty-two of hundred fifty seats. In 2023, they held forty-one. Wilders’s party lost eleven, yet JA21 jumped from one to nine and Forum rose from three to seven. In total, they control nearly one-third of the 150-seat parliament. This reshuffle is mainly tactical: once every mainstream party said it would refuse to govern with Wilders, many hard-right voters simply parked their ballot with JA21 or Forum, instead of abandoning this kind of politics altogether.

Second, the combined forces of the Left, in all their colors, have crashed to just thirty seats. The GreenLeft–Labor coalition fell from twenty-five to twenty, the Socialists from five to three. The further-left BIJ1 had already lost its single seat in 2023. It failed to regain it, and no newcomer filled the gap.

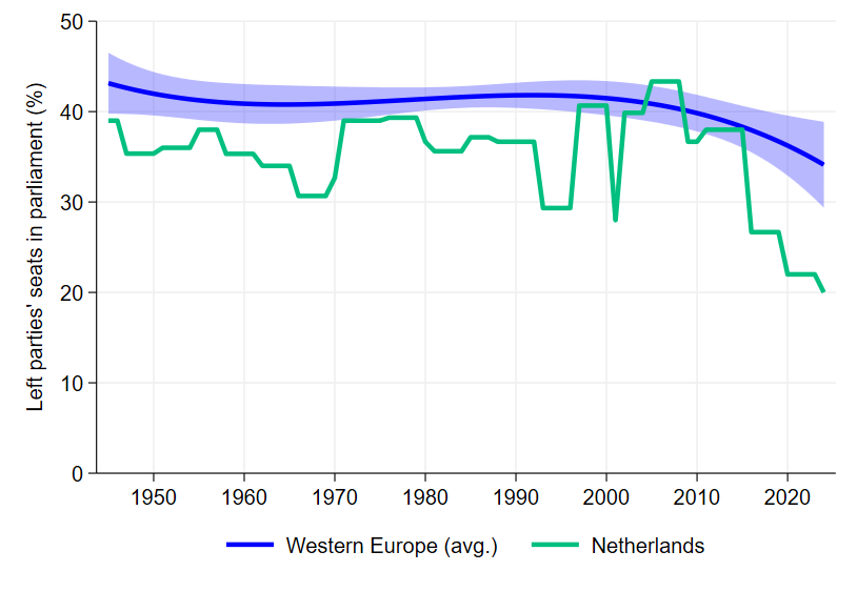

That 20 percent share of seats in parliament is the leanest left-wing bench the Netherlands has recorded since the advent of universal suffrage. This is even more remarkable given the context of this election, following the collapse of a right-wing government widely regarded as a failure. It also followed an election campaign in which economic issues (including housing and health care) were salient to many voters, which should’ve benefited left-wing parties. Despite such favorable conditions, however, they performed worse than ever.

Third, the Dutch left now lags behind all of its Western European peers; most of them by a clear margin. Across the region, social democrats, greens, and other center-left forces still hold roughly a third of parliamentary seats, as seen in the figure below. The gap first opened in the early 1980s, then widened sharply in the 1990s. A short-lived spike in the mid-2000s aside, the Dutch line has slipped steadily while the continental average has drifted only gently downward. Whereas in other countries, Green or radical left parties could at least partly offset the losses of social democracy, in the Netherlands the left-wing parties collapse in parallel to each other. Last week’s result locks the distance at its widest point in the postwar era.

These facts do not erase the relief many feel at Wilders’s retreat. They do, however, warn against declaring the tide turned. The Dutch right is still dug in, the Left is at a modern-day low, and any new cabinet will need at least four parties to govern. That, not a quick “return to reason,” is the real canvas on which the coming technocratic project must paint.

What can today’s Dutch wreckage teach the wider European left? Begin with the big structural change. The Netherlands used to be organized around three broad currents: Christian democrats, social democrats, and liberals. Since the 1990s, every election has chipped a few more bricks from the main pillars of Dutch politics until, by 2017, no party commanded even a quarter of the vote. Four years later, seventeen logos sat on the ballot. What used to be called a “three-river country” has turned into an unpredictable delta comprising any number of branches.

The Right has adapted far better than the Left. A revolving door lets angry voters move from one antiestablishment banner to the next while hardly ever leaving their ideological bloc. When Pim Fortuyn’s list burned out in the years following his assassination in 2002, voters slid to Wilders’s PVV; when Wilders looked too toxic for coalition, many simply tried JA21 or Forum instead. The supply for such voters doesn’t evaporate but only changes its jersey.

The center left, by contrast, keeps losing vessels faster than it builds new ones. The graph shows that Dutch left parties once matched the Western European norm of about 40 percent of seats. Today they hold barely 20 percent. No other Western democracy has seen such a collapse. The Labor Party (PvdA) fell from forty-five seats at the turn of the century to just nine in 2017, and its alliance with the Greens has not halted the slide. In fact, the alliance — which stands to turn into a full merger next year — reduces the revolving door capacity, because disappointed voters from one party cannot switch to the other.

The Dutch left walked into the 2025 ballot divided, unsure of its own voice, and it showed.

The historically more radical-left Socialist Party adopted the opposite pose as the GreenLeft-Labor alliance. It tried to copy the playbook of Germany’s Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance: talk tough on borders while hankering after a lost social democracy. This may have seemed a viable strategy, since the far right predictably failed to deliver on its pro-welfare promises. But voters are used to governments of all stripes failing to deliver on bread-and-butter economic issues. So those attracted to the anti-immigration message stuck with the familiar far-right narrative — which the Socialist Party helped legitimize. Progressives and voters with a migration background just turned away.

As in 2023, GreenLeft-Labor was led by former vice president of the European Commission, Frans Timmermans, who hails from the liberal flank of the Labor Party. He represents calm competence, balanced budgets, and brisk climate action — much the same package D66 has sold for years. Predictably, voters who like technocracy chose the familiar label, once this party got a shot at being an indispensable factor in the new government. D66 leader Rob Jetten topped the polls and now leads coalition talks. Timmermans’s image as a consummate Brussels veteran — and long-standing target of an effective far-right smear campaign — didn’t help him compete with the fresh face Jetten either.

The merger of red and green banners may have hurt more than it helped. Outside the Amsterdam ring road, climate policy already feels like an elite hobby. Tying Labor’s social brand to what is — rightly or wrongly — widely represented as elite, metropolitan environmentalism reinforced that hunch. In small towns where new homes are scarce and petrol is still required to pay the bills, the alliance looked distant, even hostile. And anyone who saw the old GreenLeft party as potentially more radical was forced to recognize it as yet another establishment force.

The “deep green” Party for the Animals only managed to retain its three seats in parliament. Due to divisions within the party over its support for increased military spending, throughout the campaign the party leader faced difficult questions about internal animosities. This made it difficult to gain momentum. On the left-wing activist flank, BIJ1 disintegrated in a storm of rank-ordering oppression. Rows over which community deserved top billing drowned out housing, wages, and schools. The party vanished from parliament and failed to make a comeback despite a change in leadership. Its implosion was a gift to opponents who insist the Left cares more about symbolism than day-to-day life.

Yet daily life is where the real malaise sits. The Netherlands is rich and unemployment is low, but the median voter fears her children will slip backward. House prices have doubled in a decade, private rents soar, and waiting lists for social flats stretch into years. The far right misleadingly nails that anxiety to migration, claiming newcomers price natives out of their own market and asylum seekers are given undeserved priority over the native population. Economists reply that farms and chip fabs need migrant labor at both ends of the pay-scale, but the simplistic story of “queues and overcrowding” carries more punch, especially when accompanied by the usual nativist and racist dog whistles.

Work feels less secure too. Precarious employment becomes normalized, and wages lag profits. Meanwhile each cabinet pares a little more from the welfare state. So even in a country that still ranks near the top of every prosperity chart, ordinary people sense a tightening. Like in many other European countries, many if not most ordinary people feel that the next generations are going to be worse off than them, for the first time in living memory.

There are solid left answers to those woes. A social housing building push, curbs on casual labor, a wealth tax to fund universal childcare and green industry — measures the Dutch budget could absorb better than most. But the parties that should champion them chose shortcuts: echoing the hard-right Wilders on migration or echoing the liberal D66 on prudence. Voters chose the originals.

If the Left is to regain ground, it must do what its rivals already do: speak with conviction. It needs a fresh story that is both materially concrete and emotionally resonant — something that can survive the churn of a fragmented party system. That means tying material security to an open, sustainable future, in words that have resonance beyond Amsterdam alone.

Whether the vehicle is a rebooted Labor, a changed Socialist Party or something entirely new is secondary. The message is what counts. It must be clear, distinct, and rooted in everyday worries. Until it arrives, the seats — be they on the opposition benches or in shaky centrist coalitions — will keep slipping away.