The Socialist Mayor of Schenectady

Long before Zohran Mamdani, Schenectady, New York, elected a socialist mayor who tried to make good on radical promises inside city hall. His short experiment still speaks to the challenges — and possibilities — of governing on the Left.

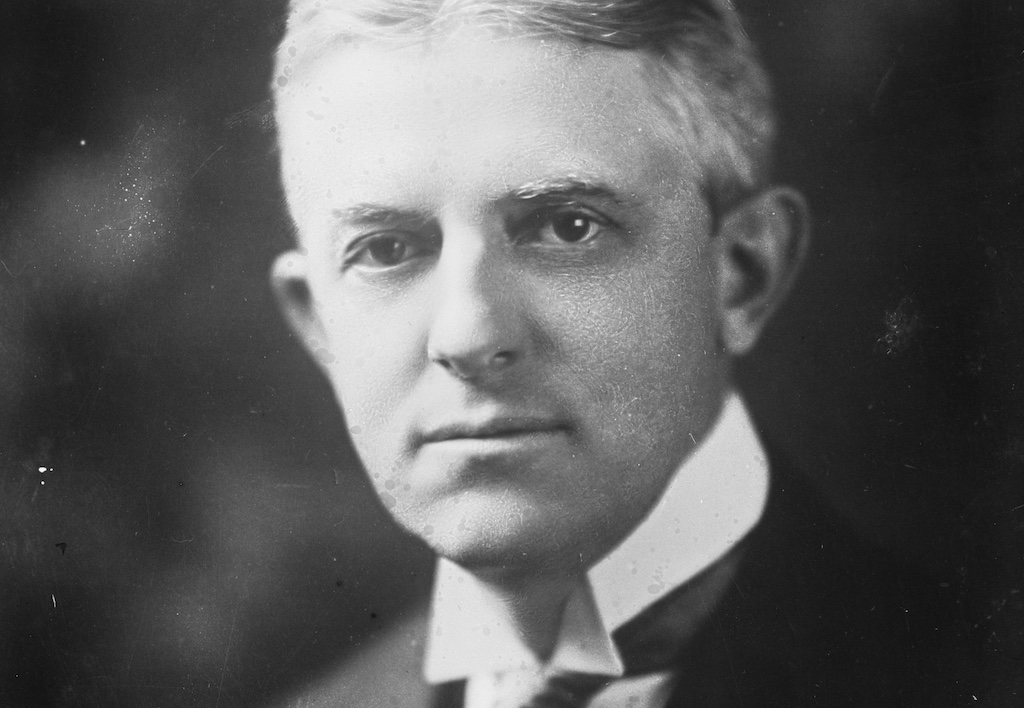

Photograph of George Lunn, 1915. (Library of Congress / George Grantham Bain Collection)

In April 1912, Walter Lippmann was feeling down. Four months earlier, he had taken what seemed to him like an exciting post-collegiate political gig: assistant to George Lunn, the newly elected Socialist mayor of Schenectady, New York, a city of about 75,000 people twenty miles north of Albany.

Lippmann’s hopes of witnessing a revolution from the ground up were soon dashed, as he found that his work entailed more paper pushing than Marxist theorizing. So Lippmann quit. In a letter he wrote to a Socialist Party colleague a year later, he reflected on his time in Schenectady. The problem, Lippmann argued, was that Lunn had been elected by a town of progressives who wanted him to pass progressive, not Socialist, policies. Concerned about his own political future, Lunn was happy to oblige.

Winning Too Soon?

On paper, George Lunn didn’t seem like much of a Socialist to begin with. Lunn was a Protestant minister who had moved to Schenectady in 1904 to work at the city’s First Reformed Church. Five years later, he had created his own congregation focused on workers’ rights — a group that, unsurprisingly, appealed to the area’s Socialists.

Those ties to the Socialist Party would propel Lunn into the 1911 Schenectady mayoral election as the party’s nominee. What Lunn lacked in political experience he made up for in political instinct. His timing was simply impeccable — socialism was on the rise across the United States, with Milwaukee, Wisconsin, having recently elected a government staffed by the party. By the end of 1912, Eugene Debs would take 6 percent of the vote in the presidential election, one of the best showings for a third-party candidate in the twentieth century.

Schenectady’s own unique political situation made it a logical place for socialism to take root. As Lippmann put it, the Democratic and Republican parties were rampant with corruption and “utterly hopeless,” meaning the city’s progressive voters — lovers of Teddy Roosevelt and William Jennings Bryan alike — were “quite ready to turn temporarily to” anyone, even the Socialists.

Lunn tried to capitalize on this mass dissatisfaction with the “old parties,” selling himself as the reform candidate of good governance who just so happened to be a Socialist. He promised some radical ideas, like opening up city-owned grocery stores, but those interventions were accompanied by basic, commonsense reforms: rooting out police corruption, giving the city more control over road paving rather than assigning the job to private companies, and overseeing important sites like dental clinics and playgrounds. His hope was to build a coalition between the block of Socialists who flocked to his church and the larger mass of progressives likely to be wooed by his mainstream reform proposals. On November 7, 1911, Lunn’s plan worked, and he was elected the first Socialist mayor of Schenectady, New York.

But in Lippmann’s recounting, the moment Lunn won, municipal socialism lost. Lunn’s coalition created an impossible dilemma for the incoming Socialist administration: Where should the “allegiance of Socialists elected by non-Socialists” lie? Lippmann thought the answer was intuitive: “The administration was elected by non-Socialists. It represents them.”

Lippmann acknowledged that an administration representing non-Socialists could still do some good things as it followed through on its mandate. It could, for example, “clean out graft” and improve playground facilities, tasks that were not “unworthy of a ‘revolutionist’” and are “good things worth having now.”

However, what such an administration could not do was actually enact anything like socialism. The basic definition of socialism, for Lippmann, was diluting returns on property and using those funds for a social benefit. Lunn’s administration certainly hadn’t been elected to do that — its mandate was limited to making some reforms while “keeping taxes where the Democrats left them.” Lunn and the Socialists would lose reelection if they increased taxes, so they “boasted” that the “first principle of their economic policy was to keep the tax rate where it was, or to reduce it if possible.” That made “the point of view” of Lunn’s administration “literally non-Socialist.” “The label Socialist will not make Socialists out of officials elected by progressives,” Lippmann explained.

The solution, as Lippman saw it, was to go back to the moment everything went wrong: when Lunn tried to win the election. Lunn was an ineffective Socialist because he had been elected by progressives, so the easy fix, in Lippmann’s mind, was to just not have Lunn elected. Rather than creating a platform designed to appeal to the masses, Socialists should have just run an “honest campaign” discussing what real socialism would mean and thus making it “extremely improbable that the great mass of progressives will swing to us.” In that scenario, Socialists could maintain their ideological purity while working toward the moment when there would be a true Socialist majority to elect a true Socialist candidate.

To gain experience in the interim, Lippmann argued that movement devotees should seek other forms of political action like union involvement and work on local committees — after all, of all the things Socialists were good at in the early 1900s, “administrative efficiency [was] not one of them.” This work would also create a basis of converts and a direct line of “propaganda” to build the Socialist majority, so that one could win an election while saving “ourselves from the embraces of fickle friends.”

“Elections are the last goal of political action, and not the first. They should come only when the social forces are organized and ready,” Lippmann argued. Otherwise, the closest that American Socialists would ever come to a revolution would be a revolutionarily efficient dentist in upstate New York.

Marching From the Margins

One hundred years later, parts of Lippmann’s letter still ring true. For the few people who have heard of the tiny city of Schenectady (and the fewer who know how to pronounce its name), it’s because there was a Charlie Kaufman movie set there two decades ago (Synecdoche, New York), not because there’s a secret socialist utopia hiding upstate. Lunn’s administration failed to transform Schenectady.

But that doesn’t necessarily render Lippmann correct in saying that Lunn should not have run in the first place. In the past century, socialist candidates have lost a whole lot of elections, and we don’t seem to be any closer to the fabled moment when “the social forces are organized and ready” to power an actual victory.

One reason for that is rooted in something that Lippmann overlooked: it’s hard to build a mass movement if one can’t see progress being made. It’s very likely that some devoted Zohran Mamdani supporters will soon feel much like Lippmann did about Lunn. But what Lippmann couldn’t see in 1913 was that something like the Mamdani administration will give the democratic socialist movement a real morale boost, not to mention an invaluable opportunity to test-run plenty of ideas. That’s good reason to be optimistic, even if Lippmann wouldn’t have thought so.

The best guide to using that optimism and avoiding the mistakes of Walter Lippmann in 1913 is, well, Walter Lippmann in 1913. A few months after his Schenectady reflection, Lippmann published A Preface to Politics. The book argued that most people had very broad ideas about how the world worked, and that they pragmatically chose policies and justifications that fit those ideas. Take Karl Marx, who “saw what he wanted to do long before he wrote three volumes to justify it. Did not the Communist Manifesto appear many years before Das Kapital?”

In other words, what mattered weren’t thousands of exclusionary rules about true socialism. What mattered were the broad outlines of socialism that leaders could follow to create policies based on a particular situation.

As much as A Preface to Politics was a sharp turn from Lippmann’s views earlier that year, the argument he landed on still applies today. If the Mamdani administration strays from the spirit of its broad promises, then democratic socialists should criticize it, much like Lippmann criticized Lunn. But unlike the young Lippmann, supporters should give the mayor room to be pragmatic rather than dogmatic. Otherwise, to quote the end of Lippmann’s Schenectady letter, they will “confuse what is already very confusing,” and doom many aspirant socialists to abandon the ideology after four months in New York City.