William Blake Was a Prescient Critic of Capitalist Alienation

Before socialism even had a name, the poet and painter William Blake saw how the Industrial Revolution’s "dark Satanic mills" harmed humanity. His visionary work condemned the forces of commodification and cold calculation in emergent capitalism.

An 1807 portrait of Romantic poet, painter, and printmaker William Blake (1757–1827) by Thomas Phillips (Universal History Archive via Getty Images)

Comparing the poet, painter, and master engraver William Blake to his contemporary William Wordsworth in a 1991 London Review of Books article, Jonathan Bate wrote that “Blake’s wildness was what shaggy men like Ginsberg needed a generation ago, but Wordsworth’s sobriety and steady eye can do more for us now.”

A generation further on, it’s time we get back to Blake, who was indeed “wild” in his radically anti-imperialist, counter-enlightenment spirit. Though some of his contemporaries would seek to brand him a reclusive madman, he was in fact an engaged, critical contributor to a larger eruption of anti-rationalist mysticism in London during this time, and not even particularly eccentric within those circles. Blake was clear-eyed about the poisonous effects that rapidly expanding commerce, industry, and empire would have on human creativity, recognizing decades before Marx’s birth how capitalist social relations alienated man from his species.

Marx and his followers would later develop a rationalist critique of capitalism underpinned by the observation that history is primarily driven by societies’ systems of production. Before this argument fully bloomed in the second half of the nineteenth century, there had been numerous radical movements seeking to overcome the existing class order, including Ranters, Diggers, Levellers, Muggletonians, and, later, the utopian socialists such as Robert Owen and Charles Fourier. Though Blake was not formally a utopian socialist, his work similarly condemns the forces of commodification, cold calculation, religious dogmatism, and hyper-accelerated worker exploitation brought on by the raging Industrial Revolution — his “dark Satanic mills.”

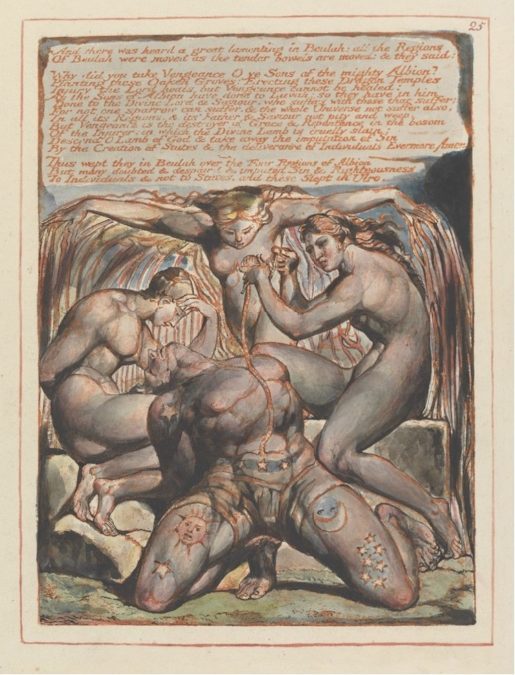

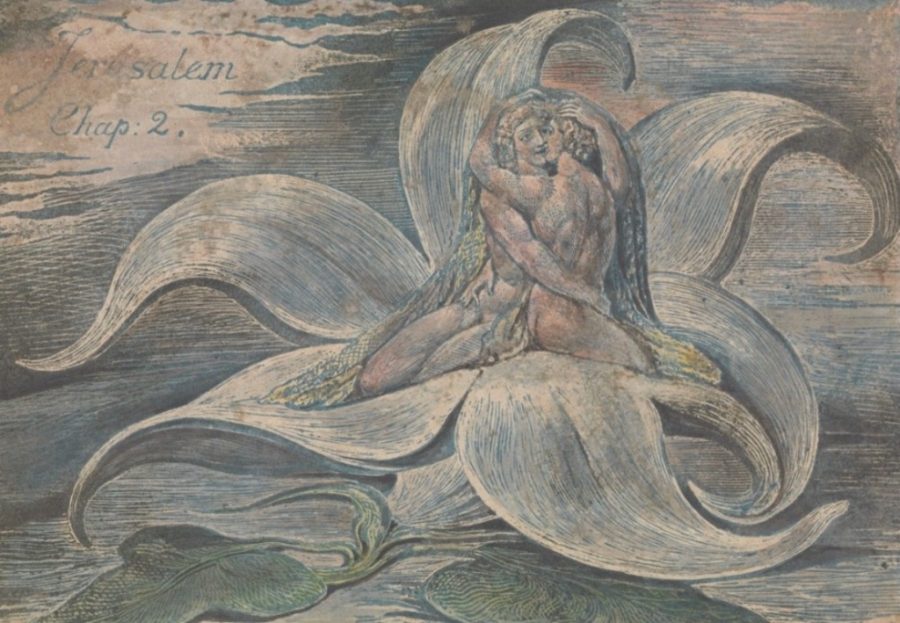

William Blake: Burning Bright, an exhibition at the Yale Center for British Art, features over one hundred of Blake’s works, including his “illuminated” books: hand-printed, spectacularly illustrated one-of-a-kind publications blending verbal and graphic art. A form of relief etching he developed, dubbed his “infernal method,” enabled him to write and illustrate on the same plate. Each work was copied in notably small numbers, often over the course of several years.

Songs of Innocence and of Experience was the first of Blake’s works produced in this way to receive attention; its poems are among his most accessible, featuring such classics as “The Chimney Sweeper,” “London,” “The Tyger” (the poem the exhibition gets its title from), and “The Lamb.” Plates from the collection dominate the first room of the exhibition.

The pastoral poems collected in Songs of Innocence are representations of childhood, where society fleetingly appears harmonious, and nature and the cosmos controlled and protected by beneficent angels. And yet children must grow, and Songs of Experience is comprised of the bleak, cruel images that they will come to recognize as they do. These poems, noted the critic Northop Fyre in his seminal study of Blake, Fearful Symmetry, “show us the butcher’s knife which is waiting for the unconscious lamb.”

The close reading of one of these poems conducted by the historian E. P. Thompson reveals how Blake chose his words deliberately to highlight not just the general condition of humanity but the specific condition of individuals in the industrializing city in which he lived. In “London,” not only are the grotesque symptoms described, but so is their cause, through constant allusions to commerce and market relations. “In a series of literal, unified images of great power Blake compresses an indictment of the acquisitive ethic. . . which divides man from man, brings him into mental and moral bondage, destroys the sources of joy and brings, as its consequence, blindness and death.”

Blake straightforwardly identifies the Church, the state, and marriage as institutions actively suppressing human potential, as well as our own “mind-forged manacles” placing harsh internal limits on our political and social imaginations. The effort to break these manacles led directly to the efflorescence of utopian socialism, which then, perhaps paradoxically, gave way to the rationalist Marxism that has characterized most socialist movements from the mid-nineteenth century onward.

Against Reason

Plates from America: A Prophecy and Europe: A Prophecy — among Blake’s most overtly political works — are also on display in this room. Here, he further develops his mythological characters; the works center around the conflict between Orc, the spirit of rebellion, and Urizen, the rationalist reaction of the law and the state. Blake used this singular mythology throughout his career to express aspects of humankind, which he saw as all “alike” yet with “infinite variety.”

Blake viewed the Enlightenment’s emphasis on rationality, standardized metrics, and abstract, generalizable likenesses across humanity and the natural world as a diabolical flattening of existence. In another work on view in this first room, There Is No Natural Religion, he warns that “the same dull round, even of a Universe, would soon become a mill with complicated wheels.”

For Blake, witnessing the American and then French Revolutions, which ultimately had secured only the “right” to trade in the global market, reason alone could never form the basis of a truly emancipatory social upheaval; this manner of thinking could only replace one tyrant with another. “And if it abolishes tyrants altogether,” suggests Frye, “it can only do so by establishing a tyranny of custom so powerful that the tyrant will not be necessary. . . . An inadequate mental attitude to liberty can think of it only as a leveling-out.” He added, “Democracy of this sort is a placid ovine herd of self-satisfied mediocrities.”

While reason would later form the basis of the Marxist critique that would become salient for industrialized workers, Blake’s more Romantic anti-capitalism was the dominant strain of radicalism in his time. Over the course of his life, Blake would perceive keenly through this lens the gradual replacement of the traditional sovereignty of the individual monarch with the laws of private property and exchange.

All Things Common

Blake was a highly heterodox Christian thinker in the antinomian (literally, “against the law”) tradition. The Christian God “makes no sense whatever,” explains Frye, “as a Supreme Bookkeeper, rewarding the obedient and punishing the disobedient. Those who labor all day for him get the same reward as those who come in at the last moment. His kingdom is like a pearl of great price which it will bankrupt us to possess.” Blake understood the hegemonic view of God as a senior accountant to be interlocked with the money economy that was proliferating and tightening its grasp in his time. “Leave counting gold! Return to thy oil and wine,” Blake writes, exhorting the financiers and bankers for whom living people are mere playthings to go do something useful with their time on earth.

As Blake biographer David Erdman notes:

The great trade expansion which was part of the industrial revolution appeared to Blake in the guise of production for war and for the markets opened by military crusades. His way of saying so in cosmic hyperbole was to declare that the whole creation was built by slave labor under “the great Work master,” Urizen.

The name Urizen (your reason and horizon) and the more comedic Nobodaddy are the mythic designations Blake gives to the joyless, unimaginative, yet powerful side of humanity that is about abstract logic and reason. “The poet’s hostility toward this ‘Governor or Reason,’ explains Erdman, “is thoroughly republican or, to the modern mind, socialistic.”

In his book Common Measures: Romanticism and the Groundlessness of Community, Joseph Albernaz takes this further, investigating critiques of measure, or the “framing of existence,” put forward by Romantic artists such as Blake who were particularly attuned to how technologies of measurement enabled the enclosure of the commons, the proliferation of the commodity form, the violent racial categorizations underpinning slavery, and the expansion of empire. Measurement is a tool used to “ground” communities, legitimizing chimeric regimes of race, class, nation, and other identities, and obfuscating humanity’s essential “groundlessness” or commonality.

Albernaz focuses on the long poem Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion, of which Yale holds the only complete hand-colored version. Plates from this work, completed between 1804 and 1820, are on view in the final major section of the exhibition. Though Jerusalem may appear to be a vast, epic, darkly impenetrable work featuring an immense cast of mythological characters, Albernaz argues that the work is ultimately an attempt to identify the groundlessness that is already present, but hidden, in the modern world.

Jerusalem, Albernaz points out, is a deeply excessive work where “characters tumble bafflingly through dozens of barely discernible nested and ringed mini-narratives.” The text and its esoteric images challenge the reader’s conception of time and space. But the work is at its core about community and the decisions a society can make in the face of human finitude and separateness. The society Blake lived in attempted to close off the human experience both physically and psychically: “The eye of Man . . . clos’d up & dark / The Ear a little shell . . . / . . . The Nostrils, bent down to the earth & clos’d . . . The Tongue . . . / . . . A little sound it utters, & its cries are faintly heard.” People were increasingly “estranged,” as Marx would later describe it, from their senses and from each other.

In Jerusalem and elsewhere, Blake sought to communicate his idea of true universal human community — beyond measure, beyond money, beyond the traditional Christian laws of “moral virtue” — residing immanently within “grounded” society, within every single atom, every single moment, every single person.

At the end of the exhibition, we come to a three-foot-long engraving, “Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales,” which Blake finished a few years before his death. The gorgeous original copper plate sits beneath it, and we are brought back to Blake as a master craftsman. Blake’s wildly vivid illustrations and inspired poems were published together in “illuminated” books and were in no way distinct pursuits, inseparable as well from political philosophy and theology. The publication of these visionary works was enabled by Blake’s inventiveness within his craft, his new method of etching making it possible to combine image and text.

While the development of a rationalist framework against class society would arrive in due course, this visionary thinker understood that the commodification of craft would come at a tremendous psychic price. This exhibition showcases a spiritual front in an infernal class war burning in England throughout Blake’s life.