Socialist Politics Can Break Through to Asian Immigrants

Politicians have long used red-baiting to win Asian American votes, assuming an aversion to anything labeled socialist. But Zohran Mamdani’s primary triumph in Asian immigrant neighborhoods suggests that economic populism can overcome ideological baggage.

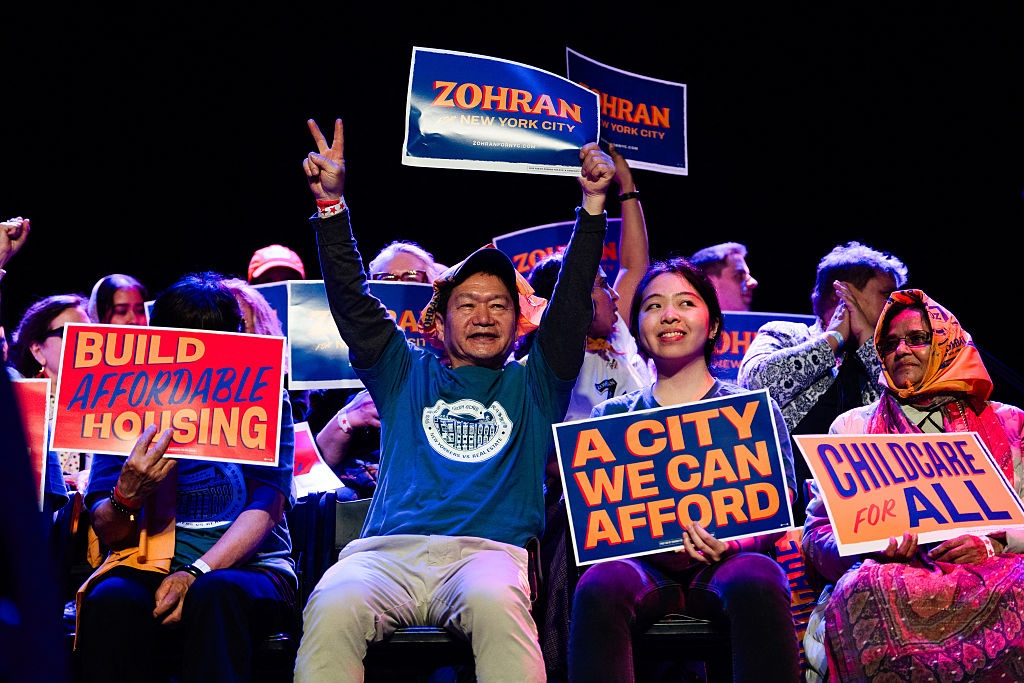

In the New York City mayoral election, Asian American immigrants are willing to gamble on a socialist, despite historical ambivalence or aversion among many of them toward the concept. (Madison Swart / Hans Lucas / AFP via Getty Images)

Two Chinese Communist Party intelligence officers sit across from each other in a windowless room, incense smoke curling up from a ceramic vessel. They’re discussing their newest asset, US congressional candidate Jay Chen.

“This Jay Chen for American Congress, he’s perfect for China,” one of them says. “He’s one of us, a socialist comrade who supported Bernie Sanders for Supreme Leader!”

“Sanders loves Mao, Chen loves Sanders,” his partner responds, before they both throw their heads back and cackle.

The two men were actors in a 2022 election ad, not spies in a B movie. Then-US congresswoman Michelle Steel, a Korean American Republican from pastel-blue Orange County in southern California, ran a campaign that stood out nationally for its McCarthyist zeal in a cycle when inflation and the economy dominated most voters’ minds. Steel, gambling that invoking Chinese communism would be enough to defeat her Chinese American opponent in an Asian-plurality district, won by nearly five percentage points.

Republicans campaigning to represent Asian American communities in Congress, state legislatures, and city councils across the country have used similar playbooks, while also exploiting interethnic tensions and fears over anti-Asian violence by tarring their opponents as soft on crime. The red-baiting strategy assumes that first- and second-generation Asian Americans from countries like China and Vietnam, where ruling parties still claim a “communist” banner despite embracing state-led capitalism, as well as people from neighboring Cambodia, South Korea, and Taiwan — whose politics are shaped by proximity or past experiences with self-styled “communist” leadership — will recoil at any mention of communism or socialism.

Such attacks build on a long tradition of Asian American leaders stoking and exploiting anti-communist feeling — from Kuomintang-friendly publications urging fervent opposition among Chinese immigrants against the mainland government to civic organizations that reported suspected leftists to federal law enforcement agencies. Republicans are hardly the only ones to use this tactic: Steel’s 2024 vanquisher, Democrat Derek Tran, turned the tables, accusing Steel herself of having even stronger communist ties.

But New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani, an avowed democratic socialist, has challenged strategists’ assumptions about Asian American immigrants’ political reflexes. In the June Democratic primary, Mamdani, running on a platform that framed left-leaning policies as a promise of liberation from economic hardship and the calculations of moneyed interests, triumphed in Asian American precincts that largely cast their ballots for centrist incumbent Eric Adams four years ago.

“[Mamdani] spoke in the universal language of, ‘I feel your pain, and I’m trying to implement policies that will make your life easier.’ To some people that may be socialism, to others, that might just be ‘economic populism.’ Either way, he spoke in a way that was not scary and that opponents would have a hard time labeling as scary,” Varun Nikore, executive director of AAPI Victory Alliance, told Jacobin. “His messaging on affordable housing, on childcare, on other issues was grounded in people’s tangible concerns.”

Perhaps surprisingly, given the community’s assumed political taboos, surveys frequently show that Asian Americans are more likely to support social services and government spending than Americans as a whole. According to Colleen Lye, a professor at University of California, Berkeley, immigrants holding a negative view of communism often associate it with corruption and political persecution, not with welfare. They “are often coming from societies in which there’s already a strong developmental state, like Singapore and Japan,” Lye told Jacobin. “When you’re accustomed to the social services that your home country has built up and might have benefited from them, your attitude toward redistribution is probably going to be much more positive.”

Mamdani performed well in the primary across New York’s ethnic enclaves, where first- and second-generation immigrants are likelier than their more integrated counterparts to congregate and find support from neighbors who speak their common language, streets that smell of familiar ingredients, and community-specific services that can lower the cost of living. His message found traction in places like Pelham Parkway, a heavily Vietnamese American neighborhood in the Bronx, where the median household income barely scratches $60,000 — about 75 percent of the city’s median household income.

Former New York governor Andrew Cuomo won the Bronx convincingly, but Mamdani pulled ahead of his rival in Pelham Parkway by ten points, even though Vietnamese American voters have long stood out as the most conservative group among Asian Americans (in a 2023 Pew survey, 51 percent of them identified with the Republican Party). Mamdani posted better numbers in other Asian neighborhoods, winning the primary by twenty-eight points in Manhattan’s Chinatown and sixteen points in New York’s Asian-majority 49th state assembly district, where Republican state assemblymember Lester Chang ran for reelection unopposed in 2024.

In New York City, working-class residents of all races are suffering from an affordability crisis that has forced many of them out of the city entirely. This, perhaps, explains why Asian American immigrants are willing to gamble on a socialist, despite historical ambivalence or aversion among many of them toward the concept.

“A lot of the intergenerational conversations that are happening right now revolve around the older generation seeing that their kids are not able to move out and afford a home because of college debt and high rents, and they have to let their kids keep staying with them,” said Lye. “There’s nothing quite as educational as seeing your kids struggle.”

From the Street to the Ballot Box

Mamdani’s primary victory suggests that electoral candidates can energize Asian American voters by embracing the same issues that drive grassroots activism in their communities. He’s done so in tandem with groups like CAAAV: Organizing Asian Communities, an organization founded in 1986 and maintained by Asian working-class immigrants alarmed by issues like anti-Asian hate crimes and gentrification pricing people out of the neighborhoods they live in.

“There’s a very long legacy of intergenerational union and community organizing in Chinatown and similar neighborhoods, with veterans passing down knowledge and ethos to younger members,” said Carolyn E Lau, a Brown University PhD candidate specializing in local resistance to gentrification. She pointed to the 1982 Chinatown garment workers’ strike, which drew 20,000 participants demanding higher wages, paid leave, and adequate cost-of-living adjustments, as a central event in the minds of Chinatown’s working-class residents.

In some neighborhoods with higher concentrations of H-1B immigrants, however, labor militancy is relatively tepid. And despite some impassioned activism, Asian Americans report lower levels of party registration and don’t turn out as often as African American and white voters, which has led to an untrue “stereotype that Asian Americans are apolitical and don’t really care about civic life,” Lau said. “If particular issues and local policies are more energizing for Asian Americans than most election campaigns,” she added, “it’s probably because those politicians are not doing enough to earn their trust.”

Taking advantage of the vacuum created by liberals’ neglect of working-class issues, recent right-wing campaigns have escalated their efforts to court Asian American voters. After the 2024 election, political pundits scrambled to publish articles about their success on that front. But Mamdani, already known in his assembly district and Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) circles for going on a two-week hunger strike in solidarity with exploited taxi drivers, charged into the vacuum with a pro-working-class platform that CAAAV Voice, the political offshoot of CAAAV: Organizing Asian Communities, delivered to over 15,000 voters in the lead-up to the primary.

Organizing by community groups like CAAAV helped lay the groundwork for Mamdani’s campaign to emerge as New York City’s most dramatic expression of left-wing, materialist politics in recent memory. Long before Mamdani’s proposed four-year rent freeze became a universal rallying cry for his supporters, CAAAV, Coalition to Protect Chinatown and the Lower East Side, and other groups representing thousands of immigrant tenants and youth, regularly advocated for a freeze at meetings of the Rent Guidelines Board. Despite those efforts, the board voted to allow landlords to raise the rent during all four years of Eric Adams’s mayoralty.

The callousness of the Adams administration and the city’s moneyed interests, CAAAV Voice communications manager Irene Hsu told Jacobin, has helped build the very class-conscious movement that seems poised to deal them the sharpest reverse in decades. “In the past, we’ve seen that politicians aligned with establishment and corporate interests create an illusion of scarcity to pit people against each other,” she said. “We intervene in this by using opportunities like Zohran’s mayoral campaign to strengthen neighborhood-based organizing — getting on streets and doors to win back our people so they are leading in a fight for a working-class city.”

Mamdani has committed himself to building an overtly socialist movement in New York City; he even personally recruited NYC-DSA’s ten thousandth dues-paying member at a canvasser appreciation party. There’s hardly a stampede of older Asian American immigrants into the DSA, even if they support Mamdani on the whole. But to be effective, socialist politics must be appealing and intelligible to people beyond a vanguard of self-identifying cadres. By putting forward a pro-working-class platform that echoes long-standing community demands, Mamdani has successfully appealed to a constituency that had appeared to be trending rightward — and may do so again in the general election — with potentially galvanizing effects for community organizing far beyond the election in November.

If working-class and immigrant communities do not fit neatly into established ideas of Left and Right, Mamdani’s campaign has been “a useful opportunity to mobilize people who may not otherwise identify with the Left, so we can organize long-term against an affordability crisis manufactured by establishment forces that have abandoned them,” said Hsu. Polls suggest Mamdani will have a chance to battle this affordability crisis from city hall and confront a revealing test of democratic socialism’s potential in the United States: how convincingly its most prominent advocate can maintain the trust and support of communities that conventional wisdom once wrote off as unreachable.