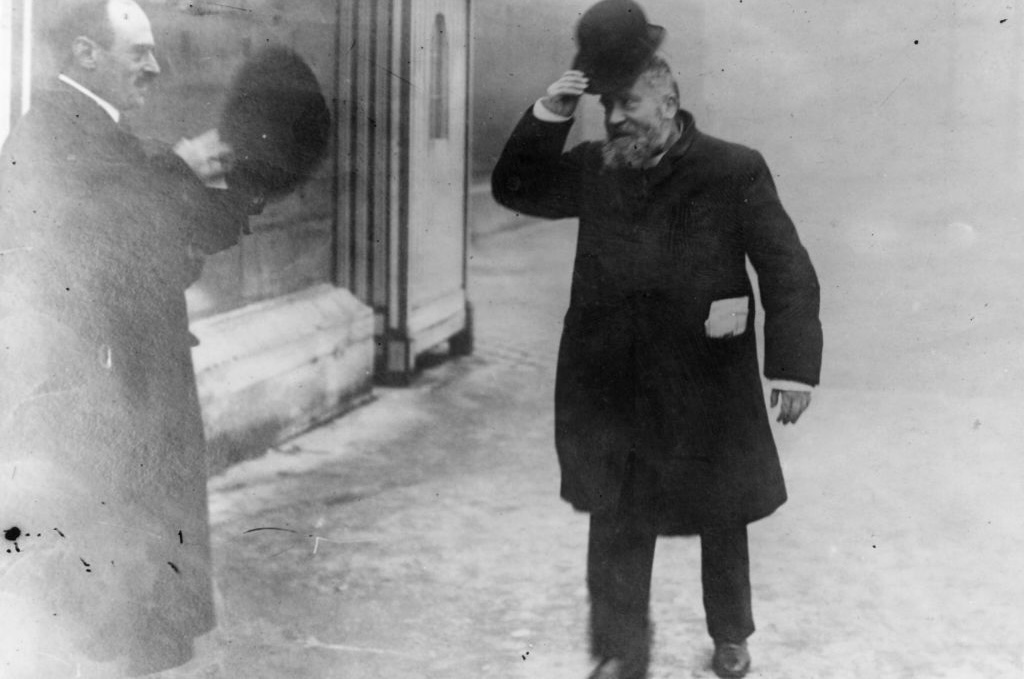

Jean Jaurès, an Iconic Leader of International Socialism

One of France’s leading socialists, Jean Jaurès was assassinated just days before the outbreak of World War I. An impassioned defender of working-class internationalism, his murder signaled Europe’s descent into war.

In Leon Trotsky’s words, Jean Jaurès was both one of the “two most outstanding representatives of the Second International” of socialist parties and the “greatest man of France’s Third Republic.” (Topical Press Agency / Getty Images)

- Interview by

- David Broder

In the years before World War I, Jean Jaurès was one of the leaders of the international workers’ movement — and he was assassinated on July 31, 1914, because of his courageous stand against the looming bloodbath. A martyr for peace, Jaurès was soon canonized both by Communists for his internationalism and by Socialists for his democratic vision of social change. In Leon Trotsky’s words, Jaurès was both one of the “two most outstanding representatives of the Second International” of socialist parties and the “greatest man of France’s Third Republic.” Founder of the newspaper l’Humanité, Jaurès’s name still has a monumental place in French public life. Yet he is today less renowned abroad than contemporary socialists such as Karl Kautsky.

Born in 1859, Jaurès began his political life as a republican and fought many battles to defend the French republic from reactionary and monarchist forces. From the 1880s, he increasingly did so as a socialist, inspired by both the radical traditions of the French Revolution and the rising labor movement. Compared to more doctrinally Marxist figures like Jules Guesde, Jaurès’s approach was more “possibilist” about gradual change within the republic’s institutions. In this vein, he took a stand in defense of army captain Alfred Dreyfus, the victim of an antisemitic smear campaign that polarized French politics between Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards at the turn of the century. At the same time, Jaurès was the champion of a united socialist party, and together with Guesde founded the French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO) in 1905.

For a century after his assassination, few of Jean Jaurès’s works appeared in English. Yet this has begun to change, with the publication of his Socialist History of the French Revolution and, most recently, a collection of his Selected Writings, “On Socialism, Pacifism and Marxism,” edited by Jean-Numa Ducange and Elisa Marcobelli. Jacobin’s David Broder, who translated the Selected Writings, interviewed the editors about Jaurès’s role in French republican history, the impact of Marxism on his thinking, and his lasting influence on the socialist movement.

Jean Jaurès is, surely, a deeply French figure, linked to the context of the Third Republic [founded in 1870 and lasting till 1940], the republican tradition, and the national political culture that made him an icon for many. His eloquence, his roots in parliamentary life, and his connection to republican history explain why he is celebrated in France even beyond the Socialist camp specifically.

However, his role was by no means solely “national.” In the Second International, Jaurès was one of the most influential voices in favor of cooperation between socialists and the maintenance of peace. In the years leading up to the outbreak of World War I in 1914, he constantly sought to mediate between different currents and strengthen international solidarity. His moral authority and authority as an orator made him a point of reference not only in France but also for many European socialist figures. That said, after his death and especially outside France, his influence proved less enduring than that of figures such as Karl Kautsky, whose Marxist theoretical elaboration lent itself more readily to circulation in the international labor movement. Jaurès, more a politician and popular tribune than a systematic theorist, remained more tied to his national context.

Jaurès became a Socialist around a decade after the crushing of the Paris Commune and the consolidation of France’s Third Republic. What did the context of the 1880s–1890s imply for his understanding of French republicanism, and what different conditions did this create compared, for instance, to that of Social Democrats in Wilhelmine Germany?

There are many aspects to consider, but ultimately the key point is this one: Jaurès was the youngest member of the National Assembly in 1885 when he was elected as a republican MP (he was not yet a socialist), and he came from a family that included several important military figures and politicians. From that time onward, and until his death, Jaurès maintained links with leading politicians who would go on to occupy the highest offices in the French Republic. Although he was hated and despised by many, he was a man of the “system,” so to speak, able to talk directly with political leaders, whereas in Germany leading Social Democrats like August Bebel and Kautsky were much further removed from the political elite. This was the case for many French socialists, including, to a lesser extent, Jules Guesde. The Third Republic consolidated in the 1880s was certainly a “bourgeois republic” . . . but a republic nonetheless. And Jaurès was fully integrated into this republican establishment — even more so than many French nationalist figures. This was a major difference with Germany, where the Social Democrats were unable to form a “republican” political coalition, even though rapprochements were beginning to emerge, with the liberals in particular, around the turn of the century.

How did the Dreyfus affair affect Jaurès’s attitudes toward the Republic, and did other socialists agree?

Jaurès chose to defend Dreyfus, who was attacked for being Jewish, because he believed that combating the nationalists’ antisemitism was a fundamental issue. However, many socialists (including Jules Guesde) did not want to defend Dreyfus because he was a soldier. As the argument went, soldiers crush workers’ strikes, so we could hardly take a stand for this one. This was a head-on confrontation and created difficult problems, even hampering unity among socialists.

In the context of the Dreyfus affair, part of the nationalist right wanted to overthrow the republic. Jaurès was determined to defend the republic and, to this end, took a very “right-wing” position for the international socialism of the time: he advocated an alliance with the republican bourgeoisie against the “hard” right. At that time (1899–1900), the entire left wing of the international socialist movement railed against Jaurès’s position, including a certain Rosa Luxemburg.

In the context of the foundation of a united socialist party (the SFIO), Jules Guesde is often seen as the more doctrinaire and “Marxist” figure. How fair is this impression? In what sense was Jaurès’s politics — and his writings on the French Revolution — specifically informed by Marxism, and what kind of Marxist culture did he have?

Jaurès wasn’t a “Marxist” in the sense of Kautsky or Luxemburg. He drew on Marxism because he was greatly influenced by reading certain texts by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels and also found value in several of the Marxist texts of his time.

For example, he wrote the preface to a French translation of Kautsky’s work on parliamentarianism and socialism, to show that it is possible to be a Marxist and an ardent defender of parliamentarianism. He had difficult debates with Luxemburg, but he read her work and listened to her arguments. We also know — unfortunately, there are few traces left — that at the end of his life he read Rudolf Hilferding’s Finance Capital . . . which he even quoted in a speech to the National Assembly at the time! In short, he fed intellectually on the Marxists of his time, while remaining a republican and distancing himself from the more doctrinaire ones. Guesde, on the other hand, had little interest in theory, and his Marxism was above all a militant tool to fuel the propaganda of the workers’ party. Guesde is much less interesting to read, but he is fascinating to study because, after all, he was the one who founded the first workers’ party with basic Marxist principles.

But what is striking, despite everything, is that Marxism was present throughout the SFIO in 1905. This would long remain the case. When Léon Blum, a friend of Jaurès, became head of France’s Popular Front government in 1936, he did not give up on his claim to Marxism . . . and until his death, he would maintain great respect for these Marxist “principles,” which were fundamental to the SFIO. This “French Marxism” was anti-Bolshevik, anti-Stalinist, rather republican and reformist, but . . . still Marxist! It was undoubtedly something quite original in Europe.

The turn of the twentieth century saw major debates in the International connected to the “revisionism” debate in Germany and also the dispute over “Millerandism,” or the participation of socialist ministers in bourgeois governments. What were Jaurès’s positions in these regards?

Jaurès’s approach was pragmatic and open, seeking to reconcile socialist ideals with the political and institutional reality of the Third French Republic. On revisionism (a theoretical debate begun in Germany by Eduard Bernstein, who proposed a reformist revision of Marxism, favoring gradual and parliamentary reforms over the revolutionary perspective), Jaurès took a nuanced position. He did not fully adhere to Bernsteinian revisionism, but neither did he share Kautsky or Luxemburg’s rigid condemnation of it.

For Jaurès, socialism should not renounce its ultimate goal — the socialist transformation of society — but could and should use the parliamentary route and social and democratic reforms as concrete tools for advancement. In this sense, Jaurès took an intermediate position: neither dogmatically revolutionary nor purely reformist but in favor of a strategy that integrated democratic achievements into the socialist perspective.

When the socialist Alexandre Millerand joined Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau’s government in 1899 — a government that also included General Galliffet, who had repressed the Paris Commune — Jaurès, unlike many other socialists, supported Millerand’s choice, seeing it as a historic opportunity to defend the republic and promote social reforms from within the institutions. For Jaurès, socialist participation in a bourgeois government was not a betrayal in itself but depended on the conditions: if it served to safeguard democracy and improve the conditions of workers, it could be justified. This position aroused strong criticism in the Second International, especially from German and Italian socialists, who saw it as a dangerous compromise with the bourgeoisie and a deviation from Marxist principles.

The Peruvian Marxist José Carlos Mariátegui insisted that Jaurès should not be counted among the “domesticated revolutionaries”; other accounts call him a great partisan of concord and conciliation. What role did social conflict and mobilization play in Jaurès’s thinking? How far did he believe in gradual change?

Jaurès was fundamentally a gradualist; that much is clear. On several occasions, Jaurès fought to defend republican institutions, when other socialists believed they should be challenged and even destroyed. He was prepared to go to great lengths to achieve “conciliation” for this cause, even beyond the republican left, and thus including part of the center right.

Still, Jaurès was also highly attentive to social issues and the inequalities generated by capitalism. He believed that class struggle existed and that strikes, even occasional general strikes, could be necessary to advance working-class demands. Other “Marxists” such as Jules Guesde, were disdainful of workers’ autonomous action and the idea of general strikes or even strikes in general.

This is why many activists much further to the Left than Jaurès have always respected him despite their differences. The syndicalist leader Alfred Rosmer, for example, left a highly significant assessment, in which he praised Jaurès for his ability to engage in dialogue with the revolutionary trade union, the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT). Upon his death, Vladimir Lenin, who disliked Jaurès’s reformism, refused to pay tribute to him. . . . But he also refused to write a highly critical text, because he knew how popular Jaurès was among the French proletariat at the time.

How far was Jaurès an opponent of French colonialism?

Jaurès’s attitude toward French colonialism was complex and not without its ambiguities. He cannot be defined as a radical and systematic opponent of colonialism, but this did not prevent him from developing a critical position.

In his early political career (say, the 1880s–1890s), Jaurès did not openly oppose France’s colonial expansion. Like other French republicans and socialists, he saw colonization as a possible means of economic progress and the spread of republican civilization, so long as it was conditioned by a universalist ideal. In the following years, however, he became more critical of colonialism. He condemned the excesses of military conquest, violence, and the exploitation of indigenous populations.

During the Fashoda Crisis of 1898, for example [a territorial clash between Britain and France in East Africa], he insisted on the need to avoid imperialist conflicts that could lead to a European war. For Jaurès, colonial expansion should never endanger peace or divert energy from the social struggle at home. Jaurès was not a consistent anti-colonialist in the modern sense of the term. He sought to subordinate colonial policy to principles of justice, peace, and social progress and severely criticized colonialism when it took violent and predatory forms.

Jaurès was assassinated just days before France entered World War I. What kind of impact did this have on the socialist movement and on the split that followed soon after?

This is a question that rears its head every time the relationship between Jaurès and the war is discussed, and it remains difficult to answer. The assassination of Jaurès on July 31, 1914, just a few days after France entered the conflict, deprived the SFIO of its most authoritative leader, its most brilliant speaker, and a staunch defender of peace. The immediate impact of his death was immense: the French and foreign press celebrated him emphatically, while his funeral offered both the political world and ordinary people the opportunity to pay a collective and moving tribute. The SFIO also received a large number of telegrams of condolence from socialist groups in various countries, including the most geographically distant.

At that very moment, France was heading toward war, and the Socialist parliamentary group decided to vote in favor of military credits, effectively joining the Union Sacrée — meaning, national unity behind the war effort. Strikingly, both supporters of peace and advocates of national mobilization invoked the legacy of Jaurès: the former claiming that he would have maintained his pacifist stance, the latter arguing that, in the face of danger, he would have put the defense of the French Republic before his loyalty to internationalism.

At the time of the Socialist-Communist split at the Tours Congress, in 1920, the late Jaurès continued to be a symbolic battleground: the Communists claimed him as a precursor of revolutionary internationalism, while the reformist Socialists celebrated him as a defender of democracy and peace. After his death, therefore, Jaurès became a shared memory but one that was sometimes interpreted in contrasting ways.

Is Jaurès, more than a martyr, a figure whose thought and example really informs the French left today?

Jaurès is indeed a martyr, but he is above all a founder and a lasting reference point, whose thinking continues to feed into a certain part of the contemporary French left, both in terms of its values (peace, democracy, social justice) and its historical identity. Politically Jaurès remains the symbol of the reconciliation between socialism and republican democracy. His insistence on the link between social progress and democratic institutions was a constant source of inspiration for the SFIO and, later, for the Parti Socialiste. On an ethical and idealistic level, his pacifism, his universalism, and his ability to conceive of socialism not as a dogma but as an open and humanist movement remain a reference point. His defense of peace in 1914 is regularly cited as an example of moral courage.

In the collective memory, Jaurès is remembered not only as a victim of the coming war, but also as a model of eloquence, intellectual commitment, and the struggle for social justice. The schools, streets, and monuments dedicated to him bear witness to his living presence in French political culture.

I believe that Jaurès did, indeed, leave a deep mark on the French left. He was one of the authors of the 1905 law separating church and state, which is still one of the most debated and discussed laws in France today. The issue of laïcité, or “state secularism,” remains a controversial one. But more profoundly, Jaurès had an impact in other areas, and I believe that many people outside France find it difficult to understand the particularities of the French left because they know nothing about Jaurès (except perhaps that he was a “reformist” with a revolutionary veneer).

In fact, Jaurès pioneered a rather original political combination. On the one hand, he was clearly a reformist, a “moderate” and a republican: he believed that socialism should be achieved in stages and that violent revolution was a thing of the past. But alongside this moderation (and this was only a relative moderation, compared to the entire political spectrum of the time), he drew inspiration from Marxism to understand the contradictions of the social and political world, whereas most of the socialist figures interested in Marxism at the time were more politically radical. In other words, Jaurès “republicanized” a Marxist-inspired socialism. This formed a hybrid doctrine that would leave a deep mark on both the moderate and radical left, among Socialists and Communists alike, and even on the far left.

Jean Jaurès is a national icon in France, celebrated by different political camps, while in the anglophone world he seems less cited by socialists today than contemporaries like Karl Kautsky. Why is that? Was his example “French” alone, and what role did he play in the international socialist movement?