W. E. B. Du Bois on Blowing Up the White House’s East Wing

The vision of W. E. B. Du Bois was one of congressional democracy, critical of presidential regimes that concentrate power in the hands of one individual — an individual who can, say, impose his vision of a White House ballroom in the sky upon all of us.

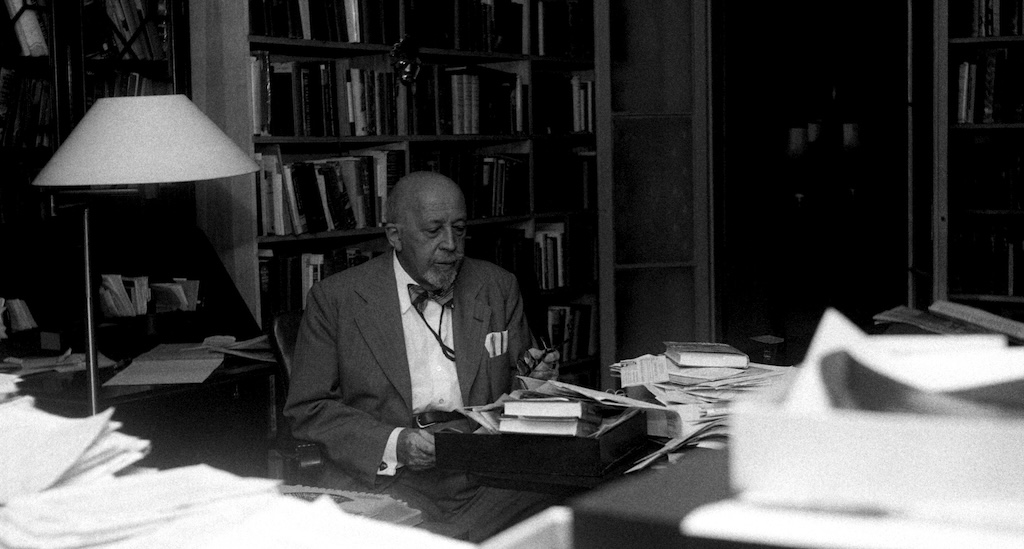

Author, sociologist, historian, and civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois poses for a portrait at home in Brooklyn, New York. (David Attie / Getty Images)

One of the elements of W. E. B. Du Bois’s argument in Black Reconstruction in America that surprised me most the last time that I taught it (or maybe the time before that), was just how much attention he pays to the Radical Republican vision of congressional power and congressional government over and against a Constitution based on presidential power and presidential government.

Du Bois even suggests that had the Radicals won, we might have had a system more like the parliamentary democracies of Europe, or at least of Britain, where the chief executive is simply the leader of the party in parliament, and not an office completely apart from that party and that parliament. For Du Bois, that vision of parliamentary government, as opposed to presidential government, was very much tied to the Radicals’ vision of racial equality and small property–owning democracy — even, at the edges, of workers’ democracy.

I bring this up as I read about Trump’s plans (after denying such plans) to demolish entirely the East Wing of the White House, which are grotesque in every way you can imagine, for the sake of building the biggest ballroom ever. Incidentally, that desire, and its frustration, is a recurrent grievance in Trump’s many complaints in one of his many campaign books prior to 2016, about how he repeatedly called the White House to offer to pay for a big new ballroom there and how Obama, snoot that he was, never would take his call.

Against Trump’s plan, the Democrats are insisting that the White House is the “people’s house.” That, too, is an old trope in American politics, but it’s flawed. It’s premised on a populist idea of the presidency, where the president is the only official in government who can speak to and for the whole people. Hamilton, as always one step ahead of everyone else, saw the possibilities most clearly: if you could make the president speak for the whole, to represent the unity of the people, Congress would be delegitimized, or at least lowered in the people’s esteem. Thus lowered, Congress would never be able to truly counter the president.

Against that vision, we have that of Du Bois and the Radicals of Reconstruction: a vision of congressional democracy. This was a vision shared by Marx, who also was critical of presidential regimes; the power of the executive and the weakness of the legislature was one of his major criticisms of the constitution of France’s Second Republic, which he made even before Louis Bonaparte established his dictatorship. It is a vision of a world that does not hinge upon what happens every four years in one election, of a world where one individual can’t impose his vision of a ballroom in the sky upon all of us, of a world in which our actions and those of our representatives, on a day-to-day, more proximate (in time and space) basis, matter most.

That, it seems to me, is what we should be working toward in the long term.