The Black Panthers Who Never Came Home

Fifty-nine years after Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panthers, Charlotte and Pete O’Neal remain in exile in Tanzania. Their story, told through interviews, archives, and firsthand reporting, reveals the movement’s enduring legacy.

Pete and Charlotte O'Neal at the United African Alliance Community Center (UAACC) in Tanzania, where they have lived in exile since 1972 (Jaclynn Ashly / Jacobin)

Charlotte Hill O’Neal is known by several names.

In Northern Tanzania, where she has lived for decades, she is known as “Mama C” because her name is hard for locals to pronounce. She is also called “Mama Africa” for her Afrocentric appearance — including Maasai cheek scarification and a labret nose piercing — and for inspiring local youth to be proud of their cultures.

Her Orisha spiritual name, Osotunde Fasuyi, was given to her during her initiation as a priestess in the Orisha tradition of the Yoruba faith — one of the world’s oldest living religious traditions.

She is also a former member of the Black Panther Party (BPP), which was founded exactly fifty-nine years ago today.

Charlotte, seventy-four, and her husband Pete O’Neal, eighty-five — the former head of the Kansas City chapter — fled the United States more than five decades ago after Pete was targeted by authorities. They have made their home in Tanzania since 1972.

Though she speaks Swahili, the official language of Tanzania, Charlotte’s lingering Midwest drawl remains a reminder of her former life in Kansas City. Her skin is decorated with tattoos of a black panther on her left shoulder and Sankofa, an Akan symbol for gaining wisdom from the past. A nyatiti, a stringed instrument traditionally played by the Luo people of Kenya, has now replaced the gun she once carried during her time in the party.

The couple now runs the United African Alliance Community Center (UAACC) in Imbaseni village outside the city of Arusha. The center’s walls are splashed with murals of black power and civil rights icons like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

Their decades-long story intertwines with the revolutionary spirit of thousands of young African Americans who attempted to stand against injustice but who were instead met with prison, assassinations, and government repression.

Community Uplift

Though their relationship is now a powerful testament to lasting love, Pete admits he “despised” Charlotte when they first met.

Pete joined the BPP in 1968 after a political awakening during a visit to Oakland, California, where the Panthers were founded in 1966. He was formerly incarcerated as a teenager, calling himself a “crook and a thief.”

“My life mirrored that of many young black men and women drawn to street life in the ghetto,” he says.

His friends convinced him to go to Oakland to see this new organization, but he initially had “no interest” in community uplift and thought he would “just do some hustles and make some money.”

Like many, the Panthers’ focus on police brutality initially attracted Pete. He told BPP cofounder Bobby Seale and high-ranking member David Hilliard that he would do anything to “get even with [the police].” But they stopped him, saying, “Brother, that’s really not what we’re all about. We’re not about getting even. We’re trying to change the world,” Pete recounts.

Pete stayed in Oakland for weeks, participating in political education sessions about global revolutionaries like Che Guevara and Mao Zedong. He suddenly had an “epiphany,” he says. “I imagine this is what happens to born-again Christians when they ‘see the light.’ Well, I saw the light.”

Embracing a cause larger than himself, the twenty-eight-year-old former street hustler returned to Kansas City, imbued with the desire for revolutionary change, “not just for black people but people of the world.” He severed ties with his former life and founded the Kansas City BPP chapter in Missouri.

Meanwhile, Charlotte was finishing high school in Kansas City, Kansas. Raised to be very proud of her “Africanness,” she was inspired by Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and the striking images of Panthers marching in their black leather, berets, and shades. At the time, she cut out pictures of Pete from newspapers and pasted them onto her bedroom walls.

“But I never thought I would actually meet him,” Charlotte says with a wide smile. Yet when she finally met Pete in person, it was far from love at first sight.

The Fiery Beginnings of a Panther Romance

Charlotte was a strong student, but she often skipped school to cross into Missouri for political education courses with the Kansas City chapter. About two months after graduating, Charlotte, then eighteen, officially joined the BPP, though Pete was away on a speaking and organizing tour.

Charlotte began living in a “Panther pad,” where young Panthers shared a communal space, modeling the revolutionary socialist society they aspired to create. Together they cooked, cleaned, and trained with weapons.

The BPP had strict conduct rules against narcotics, alcohol, or marijuana use while on duty. Members had to be “very alert,” Charlotte says, because police constantly harassed and arrested them to deplete the party’s resources. Signs around the pad warned members against being “nonfunctional.”

“But we were teenagers, and it was the ’60s,” Charlotte says, tilting her head back with a mischievous chuckle.

One day, she and other young Panthers decided to drop “red devils,” the street name for Secobarbital — a sedative-hypnotic pill used medically for insomnia and epilepsy but widely abused in the 1960s and ’70s.

“We were out of it,” Charlotte recalls. “Having a good time — everyone smoking, doing this and that. We were thoroughly nonfunctional.”

But the young Panthers didn’t know Pete was returning to Kansas City that day. “I walked in and smelled illicit substances in the air,” Pete remembers. “Weed everywhere. They were partying on the porch with the music loud.”

“So I came in on them unexpectedly and said, ‘What the hell is going on?’ Their mouths dropped, and everyone went silent.”

Charlotte was finally meeting the man whose image had covered her bedroom walls in Kansas. “I was so out of it,” she recalls. “I could hardly talk.” Pete, furious with the young Panthers, spotted this young woman he didn’t recognize — who he described as a “skinny little girl with a big fat head.” He glared at her and demanded, “And who the hell is this?”

In a nervous stutter, Charlotte said, “I-I’m Ch-ch-arlotte Hill. I’m from K-K-Kansas City. And I-I joined the B-B-Black Panther Party.”

“Who the hell let her join?” Pete snapped, turning to Charlotte and adding: “Shut up and don’t say another word!”

But Charlotte shot back. “You can’t tell me not to talk. My daddy said I always have the right to speak.” The other young Panthers gasped, Pete recalls. “They were thinking, ‘Oh Lord, she’s dead now.’”

“He was real mad at that,” Charlotte says, smiling and shaking her head at the memory of meeting the man who would become her lifelong partner. “Brother Pete ran a strict ship, and here I was talking back to him.”

“I remember thinking, I can’t stand this girl,” Pete says. As punishment, Pete forced the “thoroughly nonfunctional” Panthers to carry each other on their backs and run around. He then locked them in a storage cabinet.

Despite their rocky first meeting, Pete and Charlotte were living together and married just a few weeks later. Pete says Charlotte has since become the “love of my life, my greatest inspiration, and my best friend.”

Replacing Fear With Action

Charlotte and Pete’s relationship grew alongside the rise and fall of the Black Panther Party.

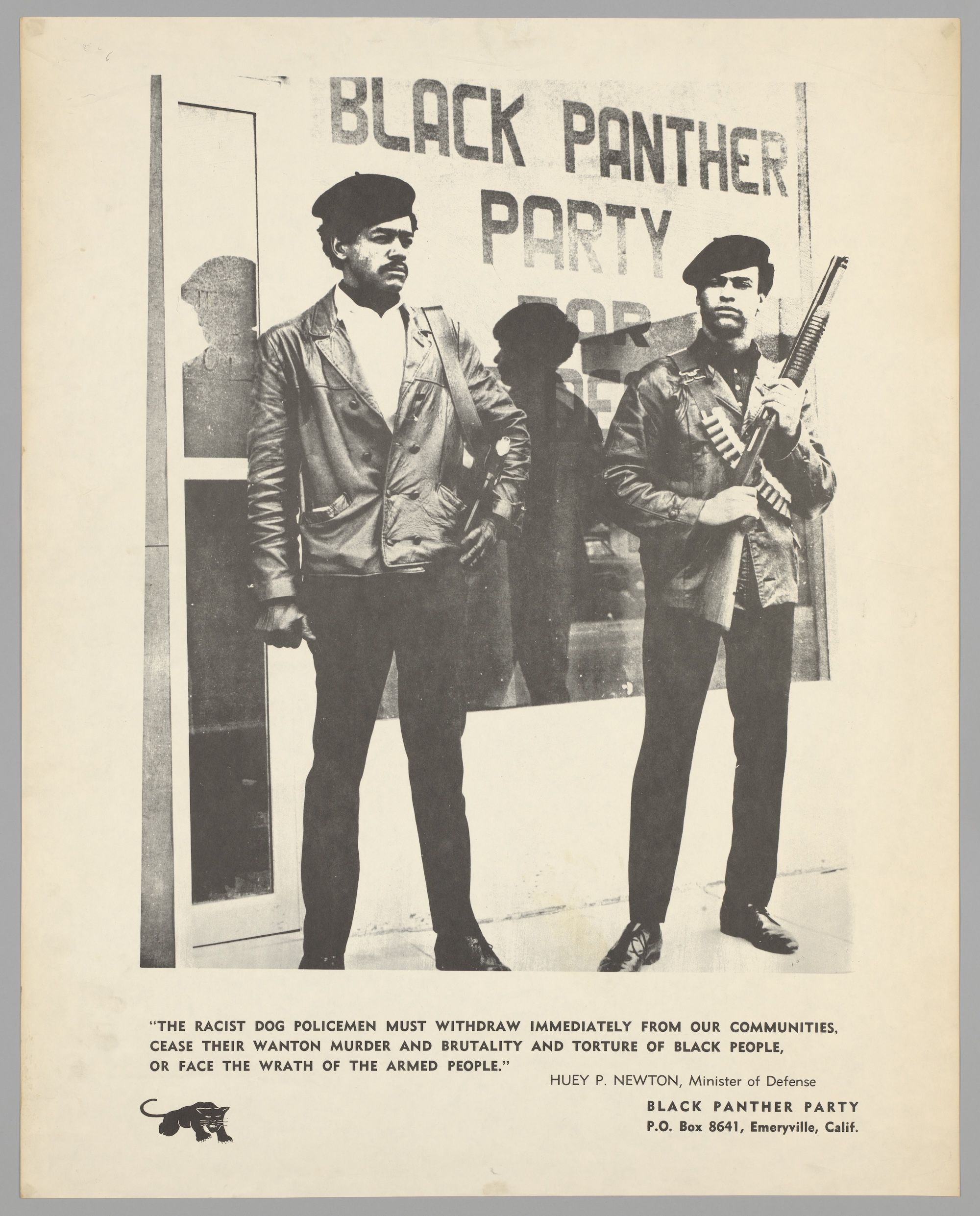

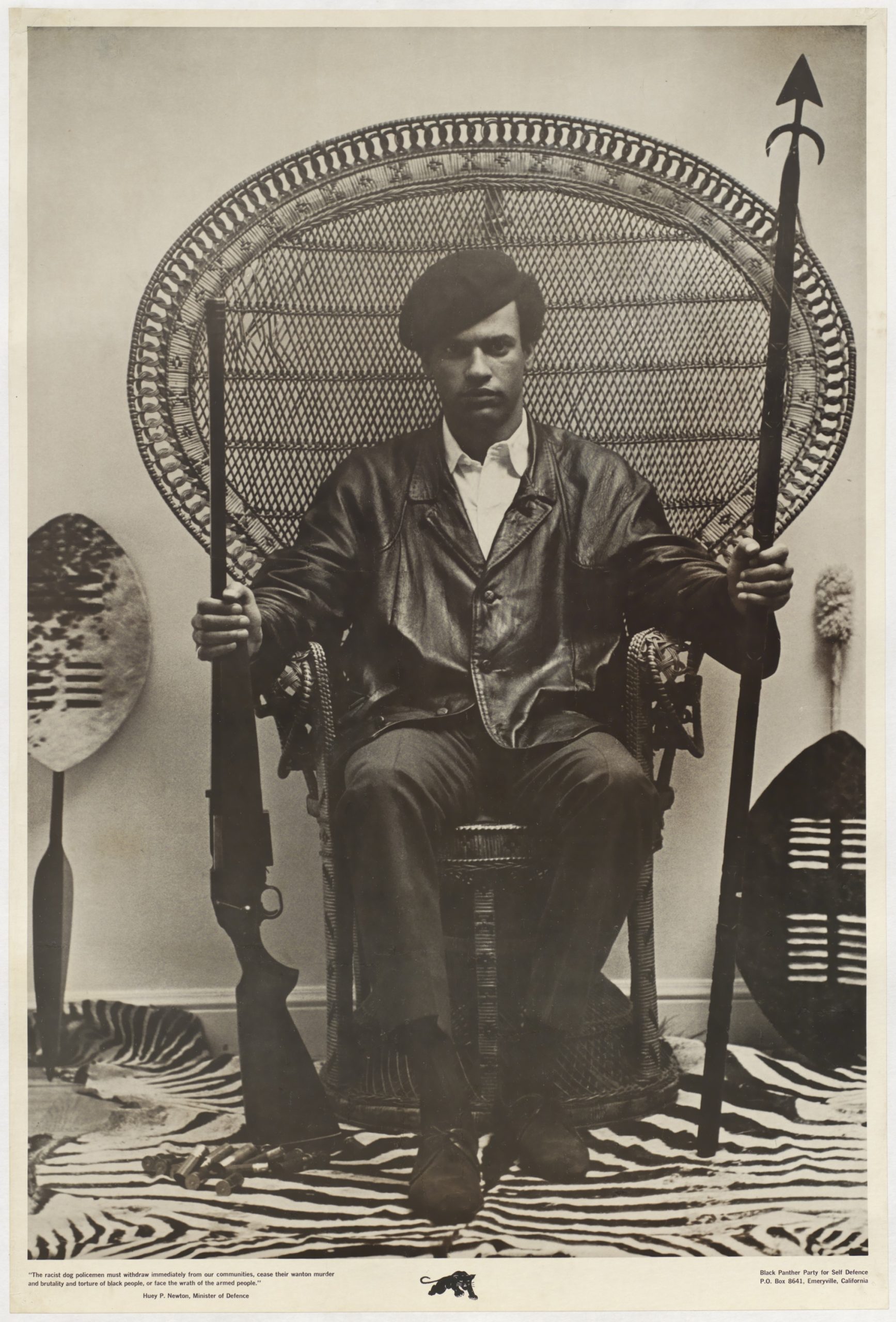

Founded on October 15, 1966, by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale at the North Oakland Neighborhood Anti-Poverty Center, the party — later labeled by the FBI as the “greatest threat” to US security — was built on a ten-point platform calling for self-determination, reparations, full employment, education centered on black experiences, and an end to police brutality, among other demands.

A central belief was the right to self-defense by organizing armed groups to defend the black community from police oppression, citing the Second Amendment. Newton and Seale understood police brutality as a daily reality for black people across age, gender, and class, notes Robyn Spencer in The Revolution Has Come: Black Power, Gender, and the Black Panther Party in Oakland.

This brutality was not just isolated misconduct but a reflection of how racial inequalities permeated law and order, with police enforcing the racial status quo. Self-defense was an organizing tool to empower a long-brutalized community.

“They viewed gun ownership and self-defense as rights long denied to people of African descent,” Spencer says. “Laws made for white people were repurposed by the Panthers for revolutionary aims.” Newton and Seale launched armed patrols of police activity in Oakland, intervening in arrests with cameras, legal books, and legally carried firearms, a sight that often drew crowds.

Many Panther members came from the military or gangs, or learned how to handle firearms through hunting, Spencer notes. “Armed self-defense was visceral and central to their image, drawing people in. But those drawn by guns had to study political education, and those drawn by politics still had to learn to handle a weapon.”

Emory Douglas, minister of culture for the party, designed caricatures of police as pigs in the Black Panther newspaper, a tactic, along with language like “off with the pigs,” that helped “replace fear with collective action,” Spencer says. By turning police from all-powerful figures into conquerable symbols, the Panthers were overturning long-established power dynamics.

Strength and Hope

In direct response to the BPP patrols, then California governor Ronald Reagan signed the Mulford Act in 1967, repealing the law allowing public carrying of loaded firearms. Dozens of armed Panthers protested by barging into the California capitol in Sacramento and disrupting a legislative session.

This audacious stunt and the conspicuous removal of a right clearly not designed for black Americans attracted even more members. The 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr, an icon of nonviolence, caused membership to swell as people sought the Panthers as a more militant alternative.

“After MLK’s murder, their doors flooded with people shocked, hurt, and angry that the leading advocate of nonviolence had been violently killed,” Spencer says.

Black Panther chapters sprang up nationwide to serve local communities, creating education programs, the Free Breakfast for School Children Program, and free medical clinics staffed by volunteer doctors and nurses. The BPP viewed its struggle as part of a larger class struggle, working alongside white activists and others from across the Left.

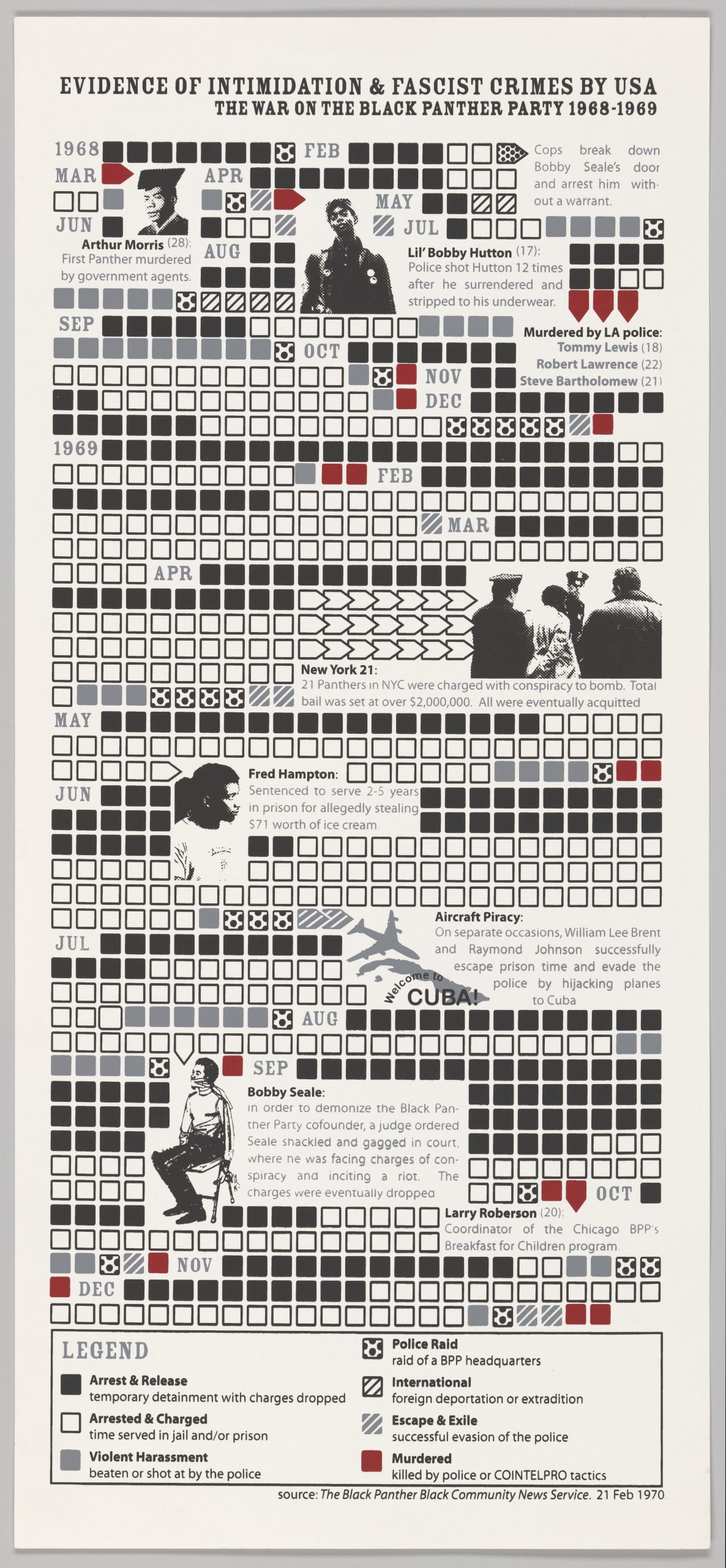

Fred Hampton, the Illinois chapter chairman assassinated by police in collusion with the FBI in 1969 at age twenty-one, famously stated the BPP would fight racism with solidarity, capitalism with socialism, and “reactionary pigs and state attorneys” with international proletarian revolution.

In Kansas City, Pete launched a free breakfast program that fed up to 700 children daily, along with clothing and food distribution, free health clinics, and police patrols. The Panthers also confronted slumlords over illegal evictions. “We’d talk to the brother in a forceful manner until he had a change of heart,” Pete recalls with a slight grin.

Despite their community work, “the news media focused on one thing: ‘A black man has a gun!’” Pete says. “They didn’t want to talk about the beauty of our community uplift programs. I was very proud of that work — it was something I had never experienced before, something as grand and altruistic as this.”

The BPP political education transformed Pete, who then dedicated his time organizing education programs for all community members, including white people.

Charlotte said these programs gave her strength and hope. “We learned about freedom movements and freedom fighters worldwide, and that’s when I began to feel part of an international community,” she says. “I still feel that way — it gave me knowledge and confidence that I continue to carry in my heart and in how I live and relate to others.”

“Down for Doubles”

Since its founding, the Black Panther Party had been under the watchful eye of local law enforcement. Police began targeting BPP vehicles and using criminal law to arrest members to drain the party’s finances with exorbitant bails and legal fees.

In 1967, the FBI expanded COINTELPRO, a counterintelligence program initially aimed at communist groups, to target civil rights and black liberation groups. By 1969, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover was calling the BPP the greatest threat to the nation’s internal security. An FBI memo suggested methods to undermine the BPP, including creating factionalism among leaders and suspicion about finances and allies. The FBI used informants, forged letters, and cartoons to create or exploit tensions, and the phones and homes of party leaders, including Pete’s, were illegally wiretapped.

On October 30, 1969, Pete was arrested for allegedly transporting a gun across state lines. This came two weeks after he and other Panthers stormed a Senate hearing in Washington, DC, with information that Kansas City police were giving confiscated guns to right-wing groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

Pete began to fear for his life. When he would arrive at court, police mocked him during searches, telling him he’d leave jail “in a box.” A black officer later warned him the police planned to kill him. Pete was sentenced to four years.

Despite his prior record, which included a prison escape, the judge allowed him to remain free on bond during his appeal, an unheard-of decision Pete believed was intended to prevent him from becoming a “martyr” in the eyes of the community. Hoover had issued a directive to “prevent the rise of a ‘messiah’” who could unify the black liberationist movement.

Paul Magnarella, a University of Florida professor and author of Black Panther in Exile: The Pete O’Neal Story, says that Pete’s 1970 trial offered “no justice.” It was riddled with “constitutional defects,” he notes. Key prosecution witnesses perjured themselves, a material witness was a paid FBI informant whose status was concealed from the defense, federal law was misapplied, and illegal FBI wiretaps were used.

Pete knew he had to run, though he initially hated the idea of leaving the United States — a plan that Charlotte, by contrast, was “enchanted” by. At the time, the US left maintained what Spencer calls a “modern-day underground railroad” — networks of people and safe houses that helped activists wanted by authorities escape the country.

Charlotte and Pete were not the first Panthers to flee. In 1968, Eldridge Cleaver escaped after being charged with attempted murder following a shoot-out with Oakland police in which seventeen-year-old Bobby Hutton — the party’s first recruit, affectionately called “Lil’ Bobby” — was killed. Cleaver later resurfaced in Algeria, where he established the Panthers’ international section. At the time, newly independent Algeria was a hub for anti-colonial movements.

When planning their escape, they couldn’t tell their families, but they believed they’d only be gone for “maybe two years.” Their home was under twenty-four-hour police surveillance, so they had to sneak out through the back, wearing disguises. Charlotte wore a wig, and Pete straightened his hair. They hid in a car trunk to get past state lines.

They ended up in Long Island, New York, where “rich white communists” set up their documents, and a lawyer drove them to the airport. Before boarding, Pete offered Charlotte, who had a full scholarship to medical school in Texas, a chance to stay.

“I told her she could go on with her life — that no one was looking for her and she’d be safe back in Kansas City,” Pete recalls. But even as a teenager, Charlotte’s response was firm: “No, brother chairman. I’m down for doubles. I’m with you all the way.”

They boarded the plane and began their life in exile.

From Underground to Overseas

Their first stop was Sweden, where they stayed for several months, before flying from Majorca, Spain, to Algiers, Algeria, where they stayed in a “bug-infested” hotel. Pete, lacking contacts, asked the owner for help reaching the local BPP.

When he called, Cleaver was “very suspicious,” he recalls. A major BPP split had formed at the time between Newton in Oakland and Cleaver in Algiers over the party’s direction: Newton focused on community programs, while Cleaver prioritized militancy and international connections.

The FBI’s COINTELPRO exacerbated the tensions. Spencer explains that the bureau viewed the Algiers section, led by Cleaver, as “particularly threatening” because of its potential to forge ties with international liberation movements and US adversaries. The FBI responded by working to isolate Cleaver from the party at home by sending doctored letters to both men to stoke distrust.

Newton began expelling prominent members from the party, including Elmer Gerard Pratt, also known as “Geronimo Ji-Jaga,” a highly respected leader of the Los Angeles chapter. After Cleaver publicly criticized Newton, Newton angrily expelled the entire international section from the BPP, resulting in a bitter split that soon turned violent.

“A lot of people died in the Black Panther Party because of this split,” Pete says. “I gave Charlotte all the money I had and told her, if I don’t come back, leave and return to Kansas City.”

When Pete arrived at the party’s Algiers office, officially called the Embassy of the African American Revolutionary Forces of North America, he introduced himself to Cleaver. “He looked me up and down,” Pete remembers. “Then he said, ‘Where the hell have you been? We’ve been waiting for you for months.’” Pete later learned his mother had sent around twenty letters to the office, knowing he would be on his way.

“They all came out so happy and excited,” Pete says. “It was pure love and camaraderie — I felt like I had finally come home.”

The Black Panther office in Algiers functioned as more than an embassy; it was a living space where members gathered, socialized, and connected with revolutionaries from across the globe — from Vietnamese communists to Palestinian anti-Zionist fighters.

But relations between the BPP and the Algerian government unraveled in 1972 after two hijacked planes landed in Algiers, bringing ransom money meant for the Panthers. The Algerian authorities seized the funds and returned them to the United States, leaving the Panthers strapped for cash. In response, the Panthers denounced the government, which retaliated by cutting their communication lines and placing them under house arrest for six days.

Coupled with Algeria’s warming ties with Washington, these tensions signaled the decline of the Panthers’ international section.

“Pole by Pole”

Hundreds of African Americans, including former Kansas City Panthers, were already living in Tanzania at the time, attracted by its first president, Julius Nyerere, an icon of militant Pan-Africanism, and his philosophy of African socialism, ujamaa.

Pete, however, had no desire to settle in Tanzania. “When things began falling apart in Algeria, I wanted to return to Sweden,” he says. “Others were going underground or trying to get back to the US, but every comrade who did ended up spending decades in prison.”

It was Charlotte who persuaded him to try Tanzania. “She pushed hard for it,” Pete says. “I took her advice — and it was the best I’ve ever received.”

Their 1972 journey to Tanzania was difficult: they were detained in Egypt for lacking a cholera vaccination card. But Charlotte was able to alter their yellow fever documentation to read “cholera,” leading to their release. They then had a “honeymoon at a really nice hotel next to the Nile River” before getting their visas, Pete says.

The Tanzanian government welcomed them as “freedom fighters and political refugees,” Charlotte recounts. She was “overjoyed by the beauty” upon arrival, but Pete, a lifelong city dweller, struggled to adjust.

“But slowly, I grew accustomed to it,” Pete says. “Now you couldn’t drag me away — I’ll be buried here.”

They lived in the coastal city of Dar es Salaam for a year until the heat and humidity began to affect Pete’s health, prompting a move inland to the cooler Arusha region. There they learned to farm and become self-sufficient. Eventually they secured four acres in Imbaseni, a quiet rural village, where they still live today.

The area was then “just bush,” with no electricity or running water, requiring them to walk five miles to collect water in buckets. Charlotte says they started building “pole by pole” with no money, often making their own bricks and constantly finding creative ways to build and survive.

Building a Village

They recycled everything, and Pete even learned to build windmills to generate electricity. They raised chickens, milked cows, hunted, and farmed beans, eventually making sausages that they sold across Tanzania for fifteen years.

The idea for a community center came later. Local elders, impressed by their work, gave them a plot of land near their home. After building a stage for classes and activities, the center became very popular, and traveling back and forth was a hassle. They decided to build the center at their home. The first classroom was for computers, followed by a building for English classes.

In 1991, they officially founded the United African Alliance Community Center (UAACC). It offers Tanzanian youth free classes in art, sewing, yoga, hip-hop, music, and video production. “Everything we do, we insist the youth take on work that shows love for themselves and then for the larger community,” Charlotte says.

While Pete has never been able to return, Charlotte raises funds for the center through annual speaking tours in the United States.

Geronimo Ji-Jaga, who was targeted by COINTELPRO and spent twenty-seven years in prison before his murder conviction was overturned, also lived in Tanzania for ten years before his death in 2011. Geronimo, who won a $4.5 million settlement from the FBI and the Los Angeles Police Department — when it was revealed that prosecutors had concealed evidence proving his innocence — gave Pete and Charlotte $10,000 to improve the village’s access to water.

After striking water, they installed a public tap that eliminated the long daily walk and later helped erect thirty-six electricity poles, giving the community access to both. Other former Panther members have supported the center as well, including Emory Douglas, who has led art classes for the students.

In 2008, they established the Leaders of Tomorrow Children’s Home, which provides twenty-eight disadvantaged children with housing at the couple’s home, education, and health care, making them an integral part of the O’Neal family.

A Lasting Legacy

Married for only a year before fleeing the United States, Charlotte and Pete’s love blossomed in exile. Together they raised two children, Malcolm and Ann Wood. And despite all the challenges, they have never had an argument.

“She’s the only one I can get truly mad at, but all I can do is shut my mouth and stay quiet,” Pete says. “If she’s upset with me, the most she’ll say is ‘Alright.’ That’s been the extent of our disagreements for fifty-six years — just getting mad and not talking.”

Pete, who originally didn’t believe in romantic love, says Charlotte changed his mind. Decades after their less-than-ideal first meeting at the Kansas City BPP chapter, Charlotte has become the energetic one, eagerly making videos, movies, and music with the youth, while Pete has settled into being more of a homebody.

“I was her older man,” Pete recalls.

I was well-traveled and schooled in the university of life. I even took her on her first plane ride — she was a child compared to me. But now it feels like the roles have reversed. I stay home and look after the children. I never thought I had a grandfather bone in my body, but now they spend the whole day with me. At night, I’ll have twenty kids packed into my bedroom and twenty parents in flip-flops waiting outside my door.

He smiles. “And I love it. This is what my exile has become.”

More than a half-century later, Pete continues to carry the trauma of police brutality in the United States. He often feels uneasy coming across local Tanzanian police — who affectionately call him Mzee, or elder, and wave for him to stop on the road. “They all know me and just want to say hi,” he says. “But I still can’t help but tense up.”

The Black Panther Party eventually collapsed in the 1980s. Huey Newton — long hounded by local authorities and the FBI, and having spent years in prison on a dubious murder charge, much of it in solitary confinement — grew increasingly paranoid and suspicious of his own members. An authoritarian atmosphere took hold, compounded by allegations of corruption and Newton’s drug use.

In 1989, Newton, still regarded as one of the most brilliant figures of the Black Power movement, was shot dead on a West Oakland street corner he had once sought to revolutionize.

Charlotte and Pete say they have strived to carry the Black Panther Party’s legacy into their work in Tanzania. “I’m a deeply flawed person,” Pete says, reclining on his bed at home as children wander in and out to shyly ask him questions. “I was then, and I remain that way today.”

“But my goal is always to be a little better than I was yesterday. I don’t always succeed — I backslide — but I hold on to the philosophy of liberation I discovered in 1968. That’s my salvation. I’m not religious, but if heaven exists, I think I’ll get in.”

For Pete, their work in Tanzania is inseparable from the party’s vision. “We see a problem and we address it. I don’t just feed my children — I feed every child. I’m proud of what we’ve built here. This is the best thing I’ve done in my life, even more than in the Black Panther Party.”

When asked if he would ever want to return to the United States, Pete answers quickly: “Hell no!”