The Anti-Tech Backlash Is Going to Grow Stronger

The deleterious impact of technology on everyday life is generating a growing backlash in Western societies. At its most radical fringe, this includes a political subculture that promotes violent struggle against technological civilization as a whole.

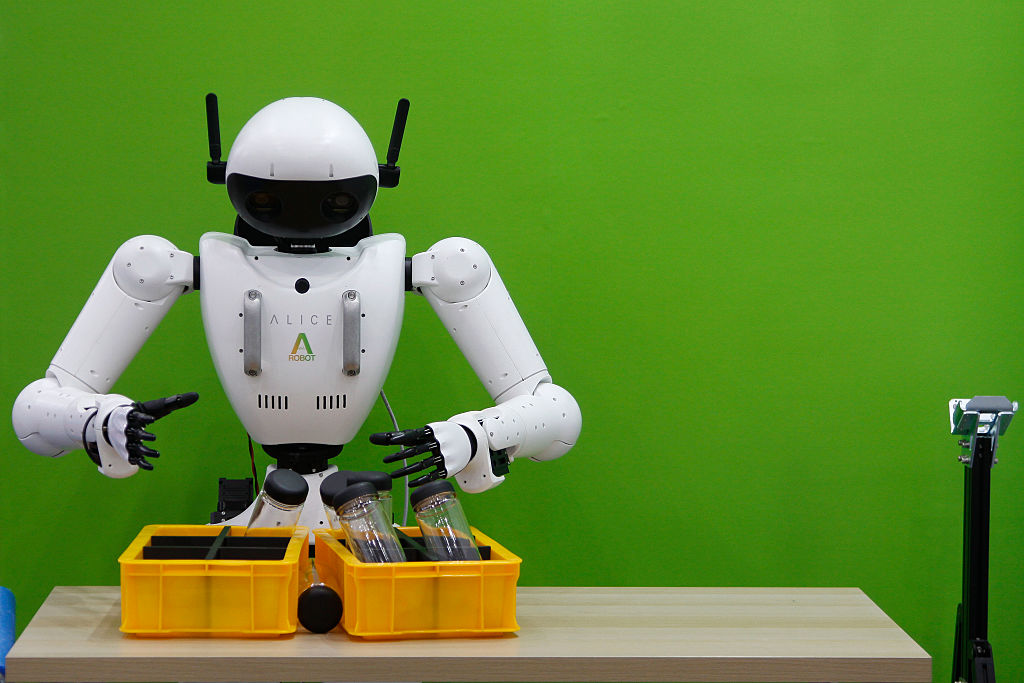

Anti-technology extremism will likely grow in significance as the impact of technology on human life becomes ever more overbearing. (Seung-il Ryu / NurPhoto via Getty Images)

In August 2011, a mail bomb exploded at the Monterrey Institute for Technology and Higher Education in Mexico. Two scientists at the institute were injured — one mildly, escaping with light burns, the other more seriously, with shrapnel from the bomb piercing his chest and perforating his lung.

At first, the Mexican authorities did not know who had carried out the attack. State Attorney General Alfredo Castillo Cervantes told the press that it might have been the action of a criminal gang, or perhaps a disgruntled student. Yet they soon realized that it had been a deliberate terrorist attack.

The bombing formed part of a campaign against scientists involved in the development of nanotechnologies. The perpetrators called themselves the Individualists Tending Toward the Wild (ITS), a group that would go on to proudly adopt the label “eco-extremist.”

The worldview espoused by the Individualists — “nature is good, civilization is evil” — sums up the ethos of a variety of groups and ideologies. Building on the legacy of figures like Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, they want to bring down techno-industrial civilization in a protracted guerrilla war against what they call “the megamachine.”

This political subculture is the subject of Mauro Lubrano’s new book, Stop the Machines. Lubrano analyzes the development of anti-technology extremism and predicts that it will grow in significance as the impact of technology on human life becomes ever more overbearing.

Three Currents

According to Lubrano, anti-technology extremism is “an ideological current that pursues the eradication of technology as a whole, not individual pieces of technology, but the whole technological system.” Looking at technology as a system in this way makes it impossible to distinguish between the positive and negative outcomes of technology. For adherents of this perspective, problems like climate breakdown, war, automation of labor, and the alienation of humans from nature are inevitable features of technology, and the only way to contest them is by attacking the system of techno-industrial society itself.

Anti-tech extremism isn’t a pure ideology that operates independently of other concerns. Rather, it combines with other ideologies to form new worldviews that share a hostility to technological society. Lubrano identifies three types of anti-tech extremist: insurrectionary anarchists, eco-extremists, and ecofascists.

Insurrectionary anarchists combine the fight against tech with their struggle against capital, the state, and the surveillance society, all of which they believe technological expansion has enabled. For Lubrano, eco-extremists meld their hatred of technology with “extremist interpretations of deep ecology” in which they take nature’s side in a war between nature and humanity. Ecofascists blend anti-technology views with white supremacy. For the ecofascist, technology as a system has allowed inferior races to “circumvent Darwinism.” They believe that whites would inevitably dominate in the state of nature to which they seek to return.

In Lubrano’s analysis, anti-tech extremists consider technology to have three components: material (steel, silicon, etc.), theological (an ideology of progress that allows technology to flourish), and human (those who create and benefit from the spread of tech). The last of these components is critical for understanding anti-tech extremism, as the would-be machine breakers regard some humans as a cog within the machine, which for Lubrano means that “to break the machine, you also have to target humans.”

He identifies one figure, Kaczynski, as the key inspiration for this outlook. Between the late 1970s and his capture by the FBI in 1996, Kaczynski sent a series of mail bombs to universities and airports that killed three people and injured twenty-seven. According to Lubrano, “if you want to be an anti-tech extremist you have to deal with Kaczynski, there is no way that you cannot. It’s like wanting to be a communist without dealing with Marx.”

Each of the three currents draws on Kaczynski in different ways. Insurrectionary anarchists embrace his distinction between tools — objects you can create yourself without relying on broader networks — and tech, for which you are dependent on others. Ecofascists draw inspiration from his primitive lifestyle, Lubrano reports: “The fact that he lived in a self-made cabin in Montana appeals a lot to their worldview.”

Lone Wolves

Although some insurrectionary anarchists don’t believe in targeting people rather than property, groups that lie within all three of the tendencies Lubrano identifies have attacked or killed people over the last fifteen years. Eco-extremist groups like the ITS and the Pagan Sect of the Mountain carried out several bomb attacks on technological researchers that seriously injured several people in Mexico and Chile (they also falsely claimed responsibility for several murders).

In 2012, an insurrectionary anarchist group in Italy called the Informal Anarchist Federation kneecapped the boss of a nuclear engineering firm in Genoa. It justified the attack in the following terms: “The science-technology pairing has never been at the service of humanity, in its deepest essence it shows the imperative need to eliminate everything that is irrational, to dehumanize, to annihilate, to effectively destroy humanity.”

Unsurprisingly, the tendency with the highest kill count is ecofascism, which has inspired several lone-wolf shootings. The Terrorgram Collective is an online network of white supremacists that circulates propaganda and encourages members of the network to kill. Thirty-five crimes have been attributed to members of the collective, including several mass shootings.

The anti-tech extremism of Terrorgram is evident in its ideology as well as the acts it promotes in the real world. Kaczynski has his place in the pantheon of “saints” that members of the network glorify. Terrorgram describes its strategy as one of “militant accelerationism,” deliberately intensifying trends to bring about collapse and reap the rewards. According to Lubrano, this approach flows from a sense that “the world as we know it will soon end and usher in something new.”

Inspired by this outlook, members of the collective carried out multiple attacks on substations in the United States in a bid to collapse the power grid. This was a practical application of anti-tech politics that aimed to reduce technological complexity while allowing fascists to take power during the chaos.

Other fascist mass shooters have also drawn on anti-tech ideas. Lubrano emphasizes that commentators have generally overlooked the anti-tech ideas contained in the manifesto of Patrick Crusius, the shooter who murdered twenty-three mostly Hispanic people at a Walmart in El Paso in 2019.

Along with his xenophobic hatred of Mexicans who were supposedly engaged in an invasion of the United States, Crusius’s manifesto draws on anti-tech ideas: “He also mentions the fact that his dream job will probably be automated. And therefore, the combination of mass migration and automation in the workplace will likely mean that all of his future dreams will remain dreams; he will not be able to realize them.”

Things to Come

I spoke to Lubrano and asked him why studying these trends is worthwhile if they operate on a relatively small scale. He argues that people often ask, “How could we not see this coming?” when new forms of terrorism break through to the collective consciousness in a spectacular display of violence.

What sets the far-right and anarchist strands of anti-tech extremism apart from previous forms of terrorism is that they are often increasingly “post-organizational,” relying on “a leaderless approach” and “networks where membership is more or less fluid.” These networks come together on apps like Telegram or Discord: ironically, it is technology itself that facilitates those seeking to overthrow the technological order.

Lubrano has conducted his work within the field of academic terrorism and political violence studies, a discipline that can make policy recommendations to states looking to deal with terrorism. I asked him about the risk that panic around anti-tech extremism could lead to a crackdown on more nuanced tech-critical perspectives, from explicit ones, like the reappraisal of the Luddites occurring in books like Gavin Mueller’s Breaking Things at Work and Brian Merchant’s Blood in the Machine, to the more implicit challenge that gig worker unions pose to the oppressive conditions generated by exploitative tech platforms.

Lubrano makes a distinction between a totalized extremist backlash against technology and the arguments of a writer like Mueller, “who says that history has not been kind to the Luddites because the Luddites were not anti-tech at all; they were against the unmitigated introduction of technology in the production process, but they were not anti-technology as such.” More broadly, he warns against a clampdown in the name of “securitization”: “If we were to respond to a surge of anti-technology violence by demonizing everyone who displays a critical perspective on technology, we’re just furthering and confirming the narrative of these groups.”

In the West, pessimism about the role of technology in society is growing. A recent Gallup News poll found that 75 percent of Americans believe that AI will reduce the total number of jobs, while just 33 percent trust that businesses will use AI responsibly. According to a survey conducted in the UK earlier this year, nearly half of those between the age of eighteen and twenty-five wish the internet had never been invented and 68 percent said they feel worse after spending time on social media.

This pessimism, particularly around AI, offers fertile soil for the spread of ideas that reject technology in its entirety. In France, the group Anti-Technology Resistance (ATR) is currently recruiting in ecologist circles and joining campaigns against the construction of resource-consuming data centers in poor areas on the outskirts of major cities like Paris and Marseille. ATR is a nonviolent group: although it refers to Kaczynksi, it draws on his later writings that advocated political organization in preference to mail bombing, with the intention “to stop and dismantle the technological system born from the first industrial revolution.”

Society, according to Lubrano, needs to “promote a different way for us to relate to technology, a way that puts humans and our relationship with our nature and one another back at the center.” Anti-tech extremists don’t pose an existential threat to society, but they are a symptom of a growing malaise associated with technological saturation. As governments in the West bet the house on AI, we can expect a backlash against tech in many different forms to continue.