If You Like Democracy, You Should Oppose Capitalism

Liberal democracy gives us essential rights like free speech and civil liberties. But without challenging the domination of capital, liberal rights will always be curtailed by the power of the rich.

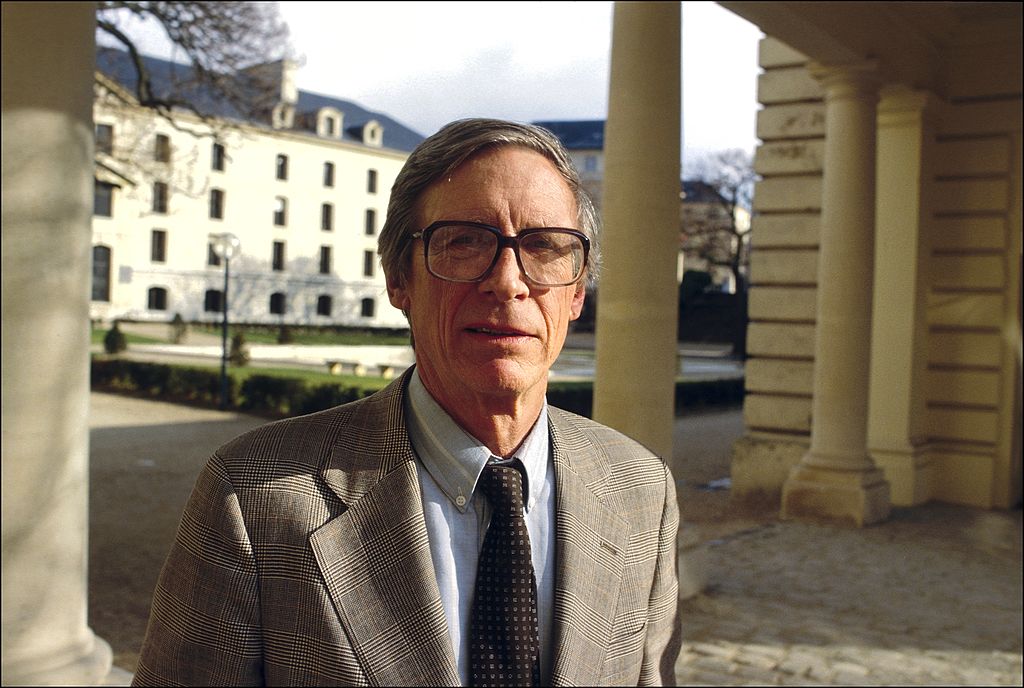

By the end of his life, philosopher John Rawls had become a persistent critic of capitalism. (Frederic Reglain / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

John Rawls was arguably the greatest liberal philosopher of the twentieth century. But by the end of his life — he died in 2002, at the age of eighty-one — he had become a persistent critic of capitalism.

In his 2001 book, Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, Rawls argued that competitive capitalism, and even an extensive Nordic-style welfare state, didn’t meet the requirements of a just society. “Welfare state capitalism,” he wrote, “permits a small class to have a near monopoly of the means of production,” which undermines two of the core principles of justice: that political liberties are held equally by all and that the social order works to the greatest advantage of the least well-off.

Rawls’s preferred alternative was a social order — either a “property-owning democracy” or “liberal socialist regime” — that would “set up a constitutional framework for democratic politics, guarantee the basic liberties with the fair value of liberties and fair equality of opportunity, and regulate economic and social inequalities by a principle of mutuality.” Firms would be democratically managed, but would still “carry on their activities within a system of free and workably competitive markets” with “free choice of occupation” also guaranteed. Unfortunately, he passed away without providing much more in the way of details.

In his great book John Rawls: Reticent Socialist (2017), the philosopher William Edmundson took Rawls’s positions seriously and worked out his radical egalitarianism in far greater depth. Now Edmundson has released a new book, Socialism for Soloists, which builds on his earlier work to contend that “justice requires socialism,” and of a liberal-democratic kind. Most innovatively, Edmundson questions the popular notion that socialists must have the bloodiest of bleeding hearts by insisting that even the staunchest individualists should be socialists.

Much of Edmundson argument is technical and scholarly. But it nevertheless arms us with extremely useful intellectual arguments in the battle of ideas.

Socialism and Equality

Edmundson’s aim is to demonstrate how an individualist commitment to liberal principles should lead to a further commitment to democratic socialism. This kind of enterprise will disappoint some leftists for its lack of political economy, and it leaves Edmundson open to the objection that his abstract moral theorizing is ahistorical and insufficiently materialist.

But to my mind, a socialism that doesn’t ground itself in a morally defensible conception of justice is one that will prove unappealing in the long run. Without a substantive, persuasive vision of the principles of justice that underpin socialism — and an account of how they cash themselves out practically — anti-capitalist critique becomes an exercise in trashing the status quo without offering any meaningful alternative. Edmundson provides us with a plausible philosophical basis for democratic socialism that doesn’t ask us all to suddenly become angels — and for that he deserves a lot of praise.

The basic principles Edmundson develops are clearly modeled on Rawls’s famous principles of justice, asking what kind of society “soloists” — self-interested and rational individualists who “recognize the pressing need for social rules and a common power to enforce them” — would choose to create through a social contract. Edmundson argues that a just society would respect a “principle of political equality: citizens who are equally able and equally motivated should have an equal chance to influence political decisions, regardless of wealth and income” and a “principle of reciprocity: economic inequality is allowed so long as it can be seen to benefit all representative social classes.”

Of the two principles he gives the second considerably shorter shrift, which is disappointing given its importance. Edmundson simply argues that individuals “contracting into” society would be willing to tolerate some forms of economic inequality if they would make everyone better off.

This is partly Edmundson’s response to the well-worn charge that socialists are motivated less by a concern for the poor than by envy of the well-off. And he is correct that any argument which says the poor can be poorer so long as the gap between rich and destitute is narrower will appeal to no one. As Edmundson points out, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels themselves weren’t strict egalitarians. In the Critique of the Gotha Program, Marx lampooned strict egalitarians, arguing that the unequal needs of equal individuals would require them to receive unequal shares to ensure the flourishing of all.

Yet Edmundson provides little sense of how much economic inequality is too much, arguing that “empirical research” may point us to the sweet spot in the future. We’re fortunate that scholars like Thomas Piketty and David Harvey are helping us fill this gap in knowledge. But it’s hard to shake the feeling that Edmundson could have provided more immediate guidance on this important point.

Socialism and Equal Political Liberties

Edmundson spends far more attention defending the socialist implications of the first principle, which is where the real innovation in his argument kicks in.

He points out that most contemporary liberal thinkers express a nominal commitment to equal political liberties for all. Yet virtually none of them have taken seriously how private ownership of the means of production — which Edmundson defines as “those resources and instrumentalities [which] . . . are widely indispensable means of productive activity (or their products are); and they are impossible to be severally owned” — fundamentally undercuts this commitment to equal political liberties for all. In a capitalist society, those individuals — including wholly artificial people like corporations — who own the means of production have far more power and influence than those who do not. They get far more value from their political liberties and can even use those liberties to exclude others from participation, ensuring even laws and regulations meant to benefit everyone equally in fact largely benefit them.

Edmundson’s argument isn’t just a principled one. He marshals both historical and contemporary evidence to show that the equal value of political liberties for all and private ownership of the means of production can never be harmonized. His evidence ranges from the immense influence of industrial capital on the politics of anglophone nations from the early nineteenth century onward to the power that modern big tech wields over the freedom of speech and expression of billions across the globe. Consequently, he says, we have a choice: either maintain our liberal-democratic convictions or accept the domination of capital.

Edmundson argues that no rational individualist could opt for the latter since it generates tremendous instability and ensures that, far from being an efficient system of cooperation for the benefit of all, political rules elevate the wealthy and powerful to still higher peaks of wealth and power. The vast majority of us are left on the outside looking in. A just society, Edmundson says, would forbid private ownership of the means of production and bring it into public hands, democratically managing the economy for the benefit of all.

This is a very powerful argument, showcasing how genuinely democratic liberalism not only can coexist with socialism but requires it.

The means of production Edmundson lists include “the currency, the highway system, the broadcast spectrum, telecommunications, power generation and distribution, navigable waterways, credit, investment banking, insurance, weaponry and munitions, airways, railways, hospitals, agribusiness, any extractive industries, petrochemicals, internet service provides, Facebook, Amazon (especially Amazon Web Services), Google, and so on.” He argues that the public takeover of the means of production could be carried out through something like the Meidner Plan (named for socialist economist Rudolf Meidner) from 1970s Sweden. The plan proposed a high tax on corporate profits paid in new stock, which would be held in a wage-earner fund managed by labor unions. Over time, workers would gain a controlling interest in all major Swedish corporations.

Beyond just public ownership of the means of production, Edmundson argues that there should be caps on the intergenerational transfer of wealth and suggests that certain kinds of public services should be provided — though which kinds are left ambiguous. He also argues that much of the economy would remain within individuals’ hands because many kinds of personal ownership don’t entail private control of the means of production. The line remains necessarily blurred, since much will depend on historical and material circumstances.

Making Liberty Real

Edmundson’s book is short — barely 150 pages — but richly suggestive and clearly argued. He builds on Rawls to show what an appealing liberal-democratic socialism might look like in the future, and demonstrates why those of us committed to the equal value of political liberties should endorse it.

The book’s biggest faults are its frustrating lack of specifics on the degree of economic inequality that would be permitted and what kinds of resources might be publicly provided. But these are minor quibbles next to the achievement of giving us a workable blueprint upon which to innovate and riff.

Socialism emerged from the French Revolution’s demands for liberty, equality, and solidarity, and democratic socialists have long prided ourselves on our concern for equality and solidarity. Socialism for Soloists reminds us that political liberty is absolutely central to socialism, too.