The New COVID-19 Relief Bill Is Good, But Not Good Enough

The good news: in passing the American Rescue Plan, Democrats are finally rejecting the logic of austerity. The bad news: the party did not use the bill to secure essential long-term economic protections for Americans, nor do anything that would anger the wealthy.

House speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer sign the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 on Capitol Hill on Wednesday, March 10, 2021 in Washington, DC. (Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

When Joe Biden signs the American Rescue Plan (ARP) on Friday, he will prove that the Democratic Party is finally willing — at least for a moment — to turn on the money hose and for once aim it not at Wall Street moguls, but instead at the raging wildfire of poverty and desperation incinerating the poor and middle class.

That’s the very good news. The bad news is that the party’s COVID-19 relief bill also indicates that Biden might have been serious when he promised a room full of wealthy donors that nothing would fundamentally change about the macro-economy’s structure.

Democrats did not use the must-pass bill to make essential, long-term changes to protect Americans against future emergencies. Instead, the party avoided including any measures that might generate significant opposition from powerful corporate lobbies in Washington. Even worse, the ARP could make it far more difficult to enact structural changes in the health care sector that has been at the center of the pandemic and that helped make our country so uniquely unprepared for such a threat in the first place.

To be sure, the package is a necessary rejection of austerity politics that have dominated Democratic politics since Bill Clinton promised in 1996 that “the era of big government is over” and since Joe Biden proudly cast himself as a deficit hawk in juxtaposition to his party’s New Deal tradition. This tectonic shift has been abrupt: When Democrats held a whopping fifty-eight Senate seats during the 2009 recession, Barack Obama listened to austerians like Lawrence Summers and passed a wholly inadequate $787 billion stimulus bill. By contrast, with Democrats only holding fifty Senate seats amid the COVID crisis, Biden rejected Summers’s and his acolytes, and passed a $1.9 trillion bill.

Biden only begrudgingly arrived at his current position. In August 2020, his campaign was telling reporters that “the pantry is going to be bare” and deficits meant “we’re going to be limited” in being able to spend any money at all. Then, in December, the New York Times reported that Biden was urging Democratic lawmakers to accept a COVID-19 aid package that included no direct aid checks at all.

After promising voters in Georgia that $2,000 checks “will go out the door immediately,” Biden quickly downgraded the amount to $1,400. The White House also entertained sharply limiting eligibility for those checks and cutting off payments to forty million Americans who received them in previous bills. (The final legislation wasn’t quite as draconian: it only penalized eleven million people.)

The larger shift against this kind of austerity, then, reflects progressive pressure successfully shifting the terms of the budget debate away from the deficit scolds and away from Biden’s own previous ideology. It also illustrates a better-late-than-never realization among Democrats that for all the nostalgia, the Obama era wasn’t all that great. Obama’s too-small stimulus delivered the weakest economic recovery in the post–World War II era, which not only ruined lives but also created the conditions for Republicans to regain power. Now, it seems Democrats have finally learned some lessons about both the economy and their own political survival.

“What happened in 2009 and ’10 is, we tried to work with the Republicans, the package ended up being much too small, and the recession lasted for five years,” said Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer of New York. “People got sour; we lost the election.”

This must-pass pandemic relief legislation — which could be the only major initiative to get through a filibuster-gridlocked Senate for some time — is being billed as “historic” because of its sheer size, and it may well have expanded the realm of what is considered possible within the confines of the existing economic structure and political paradigm.

But the definition of “possible” remains an enormous problem. Lawmakers studiously excluded major initiatives that would fundamentally alter the economy. There is nothing in its 628 pages that will make the financial system more fair and economically shield people from the next crisis or boom-bust cycle. There is very little in the bill that reduces corporations’ hegemony over our lives, requires the wealthy to sacrifice anything, regulates predatory industries, or changes the relationship between labor and capital.

If, as Rahm Emanuel once said, we should “never allow a good crisis to go to waste” because it is “an opportunity to do the things you once thought were impossible,” the Democratic Party honored the first sentiment but fell short of the second concept. Democrats did utilize the crisis for real progress — but they did not maximize the opportunity when they could have.

We live in a media ecosystem that rewards narratives over facts, and America has developed a political system that portrays politics as a root-for-the-home-team sport. The situation encourages people to view complex legislation and the players involved in binary terms of good and bad.

But that is not honest, and it is not reality. So here is a nuanced look at the good, the bad, and the ugly of the ARP — and what the legislation signals for the future.

The Good: A Mini, Temporary Version of the Great Society’s War on Poverty

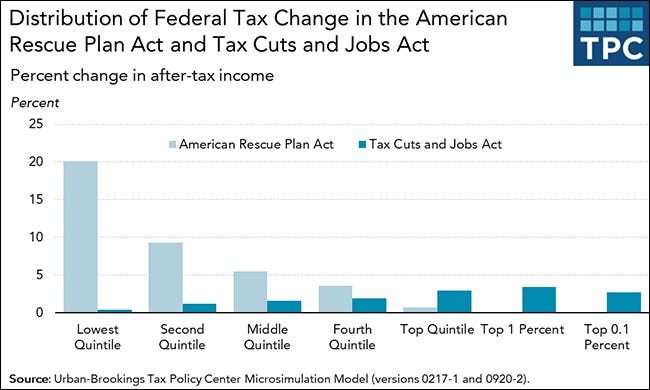

As a spending bill, the ARP’s impact cannot be overstated. It is the mirror opposite of the Trump tax cuts, targeting most of its benefits to the bottom end of the income ladder, rather than the top. It will send stimulus checks up to $1,400 to an estimated 280 million Americans, continue additional $300 weekly unemployment benefits until the end of August, and distribute up to $3,600 to families per child through monthly payments over one year beginning on July 1.

These three measures are expected to increase the incomes of the poorest 20 percent of Americans by an average of 33 percent, while the poorest 60 percent could see their incomes increase by an average of 11 percent, according to estimates from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. One estimate suggests that the legislation will slash child poverty in half.

New York magazine has aggregated other outlets’ reporting on additional important benefits of the bill including:

- More than one million unionized workers who were poised to lose their pensions will now receive 100 percent of their promised retirement benefits for at least the next thirty years.

- America’s indigenous communities will receive $31.2 billion in aid, the largest investment the federal government has ever made in the country’s native people.

- Black farmers will receive $5 billion in recompense for a century of discrimination and dispossession, a miniature reparation that will have huge consequences for individual African American agriculturalists, many of whom will escape from debt and retain their land as a direct result of the legislation.

- America’s childcare centers will not go into bankruptcy en masse, thanks to a $39 billion investment in the nation’s care infrastructure.

- Virtually all states and municipalities in America will exit the pandemic in better fiscal health than pre–COVID-19, which is to say a great many layoffs of public employees and cutbacks in public services will be averted.

Taken together, this is a miniature, temporary version of the Great Society’s War on Poverty. It shows what Democrats can do in absence of intense business opposition.

In other words, it illustrates that Democrats can at least muster the political will to ignore the deficit hawk industry in Washington and use the federal government’s money cannon for something other than enriching their Wall Street donors.

That is, to use a Biden-ism, a big f-ing deal.

The Bad: Nothing Has Structurally Changed Yet

In the year since the COVID-19 pandemic first took hold in the United States, American billionaires have gained a combined $1.1 trillion worth of wealth. The stock market hit record levels in 2020 while poverty increased faster than ever before. While the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Federal Reserve’s corporate debt buying spree propped up Wall Street, essential workers like grocery workers, postal employees, and teachers sacrificed their health and risked their lives to enrich capital.

If you were not affluent heading into this crisis, you were at risk of economic devastation from job loss, lack of savings, skyrocketing health care costs, and low wages. And while the ARP will thankfully help millions survive the next few months, it does not provide many structural fixes to the problems that created such precarity in the first place.

Yes, it strengthens regulatory agencies that police workplace safety. And yes, arcane Senate rules required it to include tiny and perfunctory tax increases on the wealthy. But it does not attempt to begin permanently reshaping the economy so that more Americans are secure the next time we face another crisis. It’s still leaving people in poverty today.

The bill’s huge and laudable investments in the basic social safety net are critical. But as the American Prospect and the Washington Post both note, the outlays are not permanent, and many will expire in short order. At the same time, nothing has fundamentally changed in the power dynamic between workers and employers.

This is the analysis for 2021. The major programs responsible for this poverty reduction are set to expire by the end of this year.

— Jeff Stein (@JStein_WaPo) March 10, 2021

No omission from the relief legislation makes that latter reality more obvious than the Democrats’ failure to include a minimum wage increase in the bill.

As its name implies, a minimum wage is the bare minimum that a government can do to structure the relationship between capital and labor. Raising the minimum wage from its historic low is extremely popular, involves few downsides, and is the absolute least that could be done to begin structurally changing the economy so that workers are protected at the bottom end of the income ladder.

And yet even this minimal reform was apparently too much. The administration almost immediately surrendered the wage hike to the nonbinding opinion of the Senate parliamentarian, an unelected adviser they could have overruled or replaced.

Senate Democrats followed the Biden administration’s wishes and removed the $15 minimum wage from their COVID-19 bill, allowing Sen. Bernie Sanders a chance to add the measure back to the bill as an amendment as a purely symbolic gesture. Even though the amendment was guaranteed to fail, eight Democratic senators spiked the football by voting against it, anyway, including the two representing Biden’s home state of Delaware.

Now, sure, you can try to argue that passing a minimum wage increase or any other measure to begin structurally fixing the economy is not within the mandate of an emergency relief bill. But that’s like saying deckhands on a cannon-battered ship should focus only on bailing out water and not patching some of the holes in the hull. The argument also ignores the reality of a Senate in which there are few must-pass bills and even fewer that can use the reconciliation process to circumnavigate the filibuster.

And pretending something like a minimum wage increase has nothing to do with the pandemic-driven economic crisis ignores data showing that, according to a recent Brookings Institution study, “a $15-per-hour federal minimum wage would disproportionately benefit the country’s essential workers” during this pandemic, because those workers comprise “approximately half (47%) of all workers in occupations with a median wage of less than $15 an hour.”

The minimum wage failure is significant not merely because it denies millions of workers a long-overdue raise that they deserve, but also for what it says about the prospects of future economic reform.

A $15 minimum wage was a wildly popular policy that Democrats promised, and yet they decided to use their power to deliberately maneuver it from a situation in which it would need fifty-one Senate votes to pass and into an impossible scenario in which it would need sixty Senate votes. Then they deviously convinced their cable TV acolytes and social media fans to cite an unelected bureaucrat to claim that this was the best the party could do.

In standing by the parliamentarian, they set a new precedent that minimum wage increases cannot be included in the reconciliation process, potentially dooming it to permanent filibuster. And they did all this even though a minimum wage increase did not face mobilized, all-hands-on-deck corporate opposition, since the current minimum wage is so absurdly low, even many business behemoths aren’t offended by the modest increase.

But Democrats had no appetite for any fight at all, no matter how mild or winnable. Congressional leaders did not have the guts to face down even the mild business opposition the initiative might face.

The White House, meanwhile, sent National Economic Council director Brian Deese to CNBC to say, “The president and the vice president both respect the parliamentarian’s decision and the process.”

And progressive lawmakers did not have the stomach or the solidarity to stand up against their own party and withhold their votes until some form of wage increase was added to the legislation.

This behavior raises a troubling question: If the Democratic Party isn’t willing to fight on something as elemental and no-brainer as a minimum wage increase, can we really expect them to fight tooth and nail for other far-reaching economic proposals that are absolutely necessary, but that would ignite a true war with corporate power?

The Ugly: Fortifying the Power of Private Insurance Corporations

It’s not great that the ARP lacks permanent measures to restructure the economy, but at least that situation can in theory be fixed with additional reforms. What’s worse is that instead of expanding Medicare or establishing a public health insurance option as Democrats promised, the final COVID-19 relief bill will deliver tens of billions of dollars to health insurance companies, further fortifying a for-profit health care system that continues to cause so much pain and suffering.

The legislation will increase and expand subsidies for insurance plans offered on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace through 2022, and it will pay the full cost of COBRA premiums through September, so people who are laid off can keep their employer-provided health insurance plans.

The expanded ACA marketplace subsidies will help millions of people in the short term, eliminating premiums for poorer families while also significantly helping enrollees who don’t currently qualify for any premium assistance because they earn too much money ($51,040 for individuals, or $104,800 for a family of four).

But the subsidy plan — based on health insurance lobbyists’ demands — is designed to herd more Americans into ACA plans that feature steep deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs. These plans leave patients dealing with ten times the amount of out-of-pocket costs as people on Medicaid.

Adding insult to injury, insurance companies denied 17 percent of in-network health claims made by patients on ACA plans in 2018, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Democrats did literally nothing to improve the quality of these health insurance plans before funneling more people into them.

Subsidizing ACA plans and COBRA coverage could also make it even more difficult to pass structural reforms to the health care system down the line.

ACA insurance plans and COBRA coverage are both very expensive, in part because private insurers pay providers double or triple what Medicare or Medicaid will. Putting more people on these plans will further boost the already outsize profits of health insurers and hospital chains and translate to bigger budgets for the corporate lobbying groups and propaganda campaigns that serve their interests.

Again, conflict avoidance came into play here. Rather than pursuing a campaign promise for a public option and igniting a fight with the health care industry and its army of corporate lobbyists, Democrats did the opposite: they spliced those lobbyists’ plan right into their legislation, giving the corporations exactly what they wanted.

To build off this political success, the health care industry’s chief front group is now airing ads to pulverize the party’s watered-down public option plan before it gains any momentum — even as the Democratic Party released a new Love Actually–themed ad touting the subsidies that will flow to health insurance companies.

By the time Democrats are ready to think about advancing some type of structural health care reform, they could easily decide it would be much simpler to once again throw more money at health insurers instead.

Hope and Change?

Beyond its policy implications, the COVID-19 relief bill suggests a few things about the present and future of American politics.

First and foremost, the bill spotlights the limits of progressive lawmakers in Congress. They had the numbers to force the legislative branch to make the bill better and include elements like a minimum wage increase. But they seemed to view the legislation through the lens of harm reduction, wagering that pushing too hard for any structural policies would jeopardize the bill’s passage and, by extension, the much-needed immediate financial relief it will provide to millions of Americans.

Their decision to go along and not wield power was a lamentable, though not surprising, calculation. The progressive wing of the Democratic Party has been so disempowered for so long that it doesn’t seem to yet have the political skills, intestinal fortitude, or will to wield power as ruthlessly as conservative party players like West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin.

The polls showing the popularity of the COVID-19 relief bill also may indicate a potential realignment in politics — but with some caveats.

It may be true, as Vox argues, that politics is now so tribalized and nationalized that a suburb-anchored Democratic Party is indeed willing to support the deployment of a money cannon to help poor people. If that holds true, that would be a significant change from the old conception of the affluent suburbs as monolithically hostile to big government fiscal policies.

But in this case, the legislation at issue asked nobody to sacrifice anything or adapt to anything, so the theory might not hold. It may just be that wealthier Democratic constituencies are willing to tolerate the money cannon, as long as nobody has to pay higher taxes, nobody has to remunerate their workers more equitably, and nobody has to pay a bit more for their DoorDash delivery.

Of course, making the bill’s investments permanent would be genuinely historic. Such a move would signal the first steps toward the kind of social welfare state that other advanced industrialized economies built for their populations long ago.

If history holds true, however, even those steps are not assured. Defeated deficit scolds will likely now amp up their complaints about the national debt, just like they did after Obama’s much smaller stimulus bill. Democrats will face a test of whether they can withstand that propaganda or succumb to a new version of a Simpson-Bowles commission aiming to try to slash social programs in the name of fiscal responsibility.

The other more imminent test will be the upcoming Democratic initiatives that could actually propose structural reform and will therefore prompt real opposition. Corporate America may have been cool with giving consumers some money to spend, but it is not going to roll over and play dead in the face of legislation to strengthen union rights, raise taxes on the wealthy, close Wall Street tax loopholes, reform the health care system, or reduce carbon emissions. And now that Democrats flinched on the minimum wage, the corporate lobby may double down on efforts to stop similar legislation in the future.

Will Democratic lawmakers really fight for people and the planet in the face of a concerted opposition? Will MSNBC-addled Democratic Party fans stop pretending the White House is powerless to do things? Will Biden actually motivate and use the power of the presidency to fulfill its promises? Will Democratic constituencies even tolerate such initiatives, if the efforts require financial sacrifice or lifestyle changes?

If the answer to these questions is no, then the ARP could still be a success — albeit a limited one. The legislation could usher in a new paradigm that is better than what we’ve had in the recent past, but not one that meets this era of existential crisis.

We could end up lurching from emergency to emergency and muscle through boom-bust cycles, holding on to the possibility that when things get really bad, the government will belatedly fire up the money cannon and do something for working people, rather than just bailing out the banks, as it had in the past.

That would be nothing to scoff at. In fact, it would be a welcome departure from the let-them-eat-cake-ism of the Reagan era. But it would not represent a return to a New Deal approach that seriously invests in economic institutions and combats precarity over the long haul.

That is the sort of moon shot we need, and the ARP could be a key step toward making that happen. But that brighter future would require Democrats to show some willingness to actually fight corporate power.

The big question remains: Does this party believe in hope and change, or does it believe nothing should fundamentally change?

The answer remains unclear — but we will find out soon enough.