How Mexico Reshaped the Global Economy

During the twentieth century, Mexican leaders shaped international institutions by demanding economic redistribution from wealthy countries to the Global South. But the system that emerged ultimately impoverished Mexico — and thwarted the ambitions of the decolonizing world.

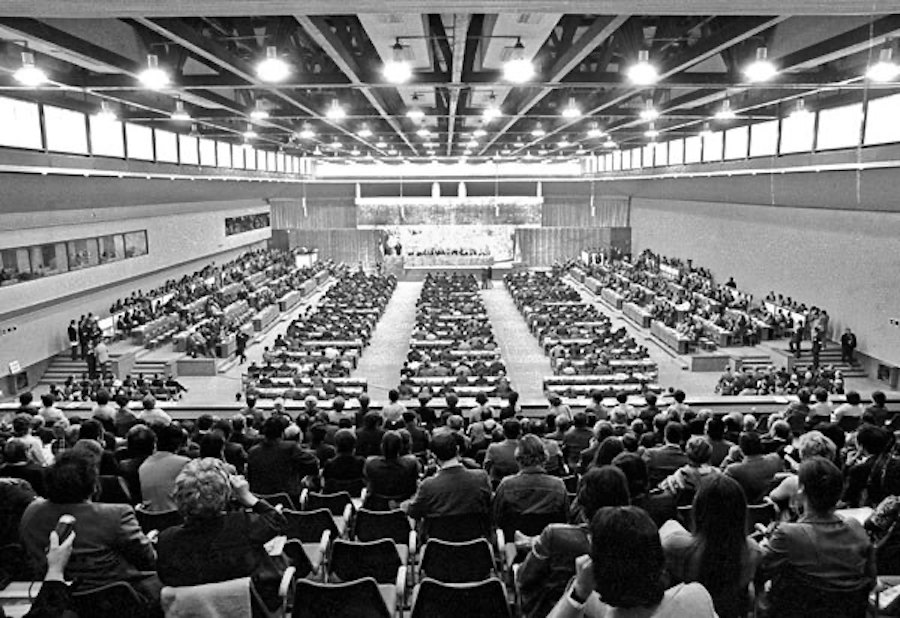

The inaugural ceremony for the third session of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development in Santiago, Chile, where President Luis Echeverría of Mexico proposed the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States. (United Nations)

- Interview by

- Jonah Walters

Only a generation removed from a world-historical revolution, Mexico enjoyed decades of sustained economic growth after World War II. But while many scholars have analyzed the country’s economic trajectory, fewer have investigated how Mexico shaped the international capitalist order itself.

A new book by historian and sociologist Christy Thornton, Revolution in Development: Mexico and the Governance of the Global Economy, adds a global dimension to the story of Mexico’s economic ascendance during the twentieth century — and its eventual ruin in the form of the 1982 debt crisis.

As Thornton shows, Mexico’s attempts to reform global economic governance played an important role in the formation of international institutions like the World Bank. But later, as Mexico became increasingly tethered to the international financial system it had helped create, the country’s radicalism eroded. By the 1950s and ’60s, Mexico was vigorously defending the prevailing system from new challenges posed by the decolonizing world.

In Revolution in Development, Thornton frames this understudied history as a cautionary tale for today’s radicals. Earlier this month, she spoke with Jacobin’s Jonah Walters about the global repercussions of the Mexican Revolution, the “undying dream” of international financial reform, and the contradictions at the heart of economic development.

What led you to write Revolution in Development?

I came to this research because I was interested in international financial institutions and the role of the Global South within them. Some of my most formative political moments were as part of the global justice movement in the aftermath of the Battle of Seattle protests. Those experiences led me to begin thinking about the role of debtor countries within international financial institutions.

When I set out to study the history of institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), I kept finding unexpected references to Mexico: it surprised me to learn, for example, that the Mexican finance minister Eduardo Suárez chaired a commission at the Bretton Woods monetary conference (1944) alongside the much more famous John Maynard Keynes.

Looking back at how international institutions were created and reformed in the twentieth century, I found that Mexico’s participation always seemed to turn on questions of property and sovereignty. The idea for the book, then, was to answer how and why this happened.

Elite Mexicans, specifically experts in the field of international finance and economics, are the human subjects of your history. They’re also, in large part, your sources. Why did you choose to focus on them?

This book draws on research from a few distinct fields, and I tried to combine a sociological focus on the state and state power, an analysis of the institutions of international political economy, and attention to historical narratives “from below.”

The people I follow in this book are mostly white, male, highly educated, powerful state representatives — not marginalized voices. But because perspectives from the Global South have been largely excluded from analyses of international institutions and global governance, these elite Mexicans occupy a paradoxical place.

When they operated in the international sphere, the people I write about were frequently derided for being Mexican and judged unfit for international economic negotiations by US and European experts. Their ideas and expertise were systematically dismissed by their contemporaries — and by many subsequent scholars.

I think of this story, then, as taking some of the lessons of Latin American histories from below and deploying them in more social-scientific debates about international governance, which have only recently begun to include voices from the Global South.

In doing this, the book builds on debates about the nature of development as an international project. A wave of post-development scholarship in the 1990s made important criticisms of the conventional view of development as a neutral, technocratic science. Arturo Escobar and others argued that development was in fact a mechanism of domination — a means through which the Global North perpetuated imperial practices of control after decolonization.

In response, however, a number of scholars argued that development could also be a fundamentally national project — the Global North and international institutions weren’t necessarily turning all the dials in the Third World. In many cases, the leaders of developmental states set policy according to domestic prerogatives, sometimes in defiance of what international creditors wanted.

This book takes the next step in this debate: It examines how Third World actors sought not just to define and implement their own national development plans but also how they attempted to reform the very international system within which those plans would be carried out.

Many of the actions Mexico takes in your book derive from the authority of the 1917 Mexican Constitution, which radically contradicted prevailing liberal notions of property. How did that constitution destabilize international relations, and why was it so threatening to the architects of US imperial power in the hemisphere?

The Mexican Constitution of 1917 is what historian Greg Grandin has called “the world’s first fully conceived social-democratic charter.” It was the first constitution in the world to do things like guarantee labor rights, limit the length of the working day, mandate equal wages for women and men doing equal work, and guarantee universal secular education.

But one of the most important things it did was to define property rights very differently from the reigning liberal conception of property. Rather than being vested in individual owners, property was defined in Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution as vested in the nation. This didn’t mean the state owned all the property, land, and subsoil resources. It meant that the state was responsible for seeing to the equitable distribution of that property, in the service of the public good.

This redefinition immediately caused uproar among foreign interests with investments in Mexico — in petroleum, mines, railroads, and agricultural land, especially. For the state to assert itself as the arbiter of how property was distributed was taken as a massive affront not only to international capitalists but also to the representatives of liberal states like the United States and Great Britain.

The Mexican Constitution set up a fight that would continue throughout the twentieth century about the economic sovereignty of poorer, weaker, and debtor states in the world order. What kind of limits could these countries place on the prerogatives of international capitalists? This became a key question throughout the Third World in the decades that followed.

How and why did this fight over Mexico’s economic sovereignty become one to reform international economic governance?

One of the many consequences of the Mexican Revolution was the destruction of foreign property holdings and the failure to pay many types of foreign debts — and the 1917 Constitution seemed to codify Mexico’s repudiation of these foreign claims.

As a result, Mexico was systematically excluded from the international financial system by Washington and Wall Street for more than twenty-five years, and it was during this period that Mexican leaders began to champion the idea of forming new institutions that could be fairer to the Global South.

Mexican state representatives had two objectives when they approached international economic governance: representation and redistribution. In fighting for representation within international institutions, Mexican officials began to argue as early as the League of Nations negotiations in 1919 against a hierarchical understanding of international affairs — the idea that stronger and richer states should get to make decisions for weaker and poorer ones.

By the late 1920s, as Mexico’s bilateral negotiations with its creditors (mostly New York and London bankers) faltered repeatedly, Mexican officials began to argue not just for representation in international decision-making bodies but also for the redistribution of surplus capital from the North to the South.

A key moment came after the Mexican foreign minister, José Manuel Puig Casauranc, proposed what he called a “new legal and philosophic conception of credit” at the Inter-American meeting of 1933 in Montevideo, Uruguay. There, Puig argued that the credit form itself had come to unfairly structure international relations. Recognizing that capitalists in the United States and Europe required productive foreign outlets for their surplus capital, he pointed out that creditors needed the debtors just as much as the debtors needed them.

Puig therefore advocated a reciprocal relationship in international finance. He and his collaborators wanted a new set of financial rules and institutions that would prevent the kind of predatory financial speculation that had proven so destructive during the Great Depression.

By the 1930s, then, representation and redistribution became the twin pillars of the Mexican state’s interventions in discussions about international economic governance.

And as your book shows, Mexico was surprisingly successful at shaping the international development apparatus in its interests, especially in the first half of the twentieth century.

That’s one of the most remarkable things about the story: Mexican state actors were able to repeatedly convince US government officials of the importance and logic of their ideas. Particularly in the New Deal period, as other scholars have also shown, there was a multidirectional exchange of expertise through which Mexican officials had tangible influence on policymakers in the United States.

When the World Bank was established under the title “International Bank for Reconstruction and Development,” for example, that was because Mexican and other Latin American actors had been arguing, over the preceding decade or more, that such a bank could — and must — channel the surplus capital of the North to productive use in the South: that it should tackle not just the reconstruction of Europe but also the development of the poorer countries.

Once that capital actually started flowing, however, Mexico’s oppositional stance eroded. As an unintended consequence of their advocacy in the early part of the century, Mexico spent the 1950s and ’60s defending institutions like the World Bank and the IMF from more radical challenges from left governments in newly decolonized countries, which felt excluded from the system that Mexico had helped establish.

Mexico is famous for its rapid economic growth in the mid-twentieth century. This growth was accomplished, in large part, by a “import-substitution industrialization” (ISI) strategy, through which an interventionist Mexican state collaborated with the private sector to lessen the country’s reliance on imported products and foster domestic industry. How should we understand the “Mexican miracle” in the international context?

The Mexican miracle was a period of high growth — around 6 percent a year — that took place from the 1940s to the 1970s. During this time, Mexico was rapidly industrializing, the population was surging, and new middle classes were developing. It was the period during which the state’s import-substituting development model really bore fruit.

But even in the import-substitution industrialization period, some of the most dynamic and important sectors of the Mexican economy were driven by foreign investment. We tend to think of Mexican ISI as emblematic of independent national development, but in many ways it involved a deepening reliance on foreign investment and trade, especially with the United States. Protecting that investment was key for the Mexican state, and the actions it took in the international sphere during this period reflected a desire to keep investors happy and foreign capital flowing.

Of course, this period was also characterized by the consolidation of a single-party state under the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). The social compromise the party engineered was based on the state overseeing the national investment strategy and mediating any conflict between capital and labor — what they called tripartismo, and what today we recognize as a kind of corporatism.

This compromise, however, was achieved through a political system that was increasingly dominated by a soft-authoritarian single-party politics that was willing to violently repress any dissent expressed outside these corporatist channels. As the urban working classes swelled and the rural poor felt increasingly left behind, it was becoming clear that there were many Mexicans who weren’t experiencing anything like a “miracle.”

You characterize the proposals Mexico put forward in the 1970s as a “global corporatist compromise.” How did the PRI’s tight control over domestic politics come to shape the Mexican state’s vision of global economic governance?

When Nixon ended the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in 1971, the United States also levied a new 10 percent import tax — a potentially damaging unilateral action to a Mexican economy increasingly tied to US markets. Mexican president Luis Echeverría tried to mitigate the crisis by creating new regulations for international investment and trade explicitly modeled on the corporatism they had constructed at home.

To that end, Mexico proposed the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States in 1972, and spent two years negotiating it at the UN. To head off the more radical challenge from countries like Cuba, Chile, and Algeria, Mexican officials argued, they needed to create an international version of the tripartismo they had created at home.

Mexican official Porfirio Muñoz Ledo argued, for example, that the developing countries were akin to workers and the industrialized countries akin to capital, and what was needed were “good collective contracts” that would resolve the looming conflict between them. The charter was supposed to be that kind of contract.

But Mexico’s domestic repression was also an important factor in the context of the Cold War. One of the key arguments that Echeverría made to US officials like Henry Kissinger was that he was uniquely positioned to mediate the growing international economic conflict between North and South precisely because he had been so good at repressing left dissent at home. The charter, he argued, was a necessary reform that would prevent those further to his left from fomenting revolution.

After two years of negotiations, the charter ultimately passed in the UN General Assembly, with a hundred twenty countries voting to approve it in late 1974. But US business interests ensured that the United States voted against the charter, and the whole episode convinced some in the foreign policy establishment that the UN had definitively turned against the United States. This launched a new right-wing doctrine in US foreign policy that would come to dominate in the 1980s.

Your book ends on the cusp of the 1982 Mexican debt crisis, at a moment when what you call the “unintended consequences” of Mexico’s international developmental vision were coming into stark relief. How did the financial institutions Mexico helped create ultimately bring about the end of Mexican developmentalism?

While there was continued work in the late 1970s on the North-South question, culminating in the 1980 Brandt Commission Report, Reagan’s election in the United States ensured there would be no redistributive North-South compromise.

Even without that framework, however, foreign capital, driven by the petrodollar boom, continued to pour into Mexico. The government borrowed increasingly large sums to spend on social programs and state investment. Mexico’s foreign debt ballooned under Echeverría and his successor, José López Portillo, surging from $4 billion to $50 billion during the 1970s, and then skyrocketing to over $80 billion in 1981 alone.

When it was announced in 1982 that Mexico couldn’t meet its foreign obligations, the country had taken on so much debt that it was a systemic risk. If Mexico went down, it could take Wall Street with it. The US government stepped in to intervene, creating a rescue package with the private banks and multilateral institutions like the IMF and World Bank.

This agreement kept the Mexican government afloat but required the radical reorientation of Mexican economic policy. World Bank structural adjustment programs were put into place to oversee the privatization of state-owned businesses, the lowering of tariff rates, the reform of the tax system, and the weakening of organized labor.

This marked the beginning of what today we call the Washington Consensus. Of course, liberal economists and many business leaders in Mexico were all too happy to see these “free-market” reforms put in place with the help of the international institutions, as well.

Thus, by the 1980s, the very international institutions that Mexican officials had spent decades demanding, building, and defending ultimately became important architects of the neoliberal transition. In the end, these institutions were used to dismantle the state developmental project itself.

You’ve said that Revolution in Development is, on one level, a cautionary tale. What do you mean by that?

I think there remains a consensus among many development scholars, development practitioners, and some leaders in the so-called developing world that if we could only come up with the right rules for global capitalism and create the right kinds of international institutions, we could finally solve the problems of poverty and inequality that plague us. In this way, the hope that successful development will finally be achieved with the right reforms of international institutions remains an undying dream.

The book attempts to show the mechanisms by which Mexico’s pursuit of that dream helped to shape the apparatus of international development itself. But it is not, on the whole, a heroic story of resistance from below, or merely a reclamation of the agency of the Global South in international affairs. It’s a cautionary tale because it’s a story that should be read as much for Mexico’s achievements as for the limits they encountered.

The book shows how, for example, time and again, even when Mexican experts convinced US government officials to accept their ideas — convincing them to create the Inter-American Bank in 1940, or negotiating deep reforms to the proposed charter for the International Trade Organization in 1948 — they could be stymied by the organized power of capital. Mexican proposals that could be useful for US geopolitical and financial power were appropriated and incorporated into agreements and institutions. But those that fundamentally challenged the prerogatives of international capitalist interests were defeated again and again.

As scholars and activists think about South-South cooperation and international economic reform today, I hope this book offers lessons about the ways that Mexico’s reform campaigns — intended in some ways to save global capitalism from itself, to make it work for the poor countries as well as the rich — were co-opted, deflected, and/or rejected.

Returning to this history can help us see the possibilities, but perhaps more importantly the limits, of such reform.