Newspapers Won’t Save Us

Newspapers are a key part of a healthy press that is vital to any democratic society. But we shouldn’t valorize the corporate media as our last line of defense against Trump or anything else.

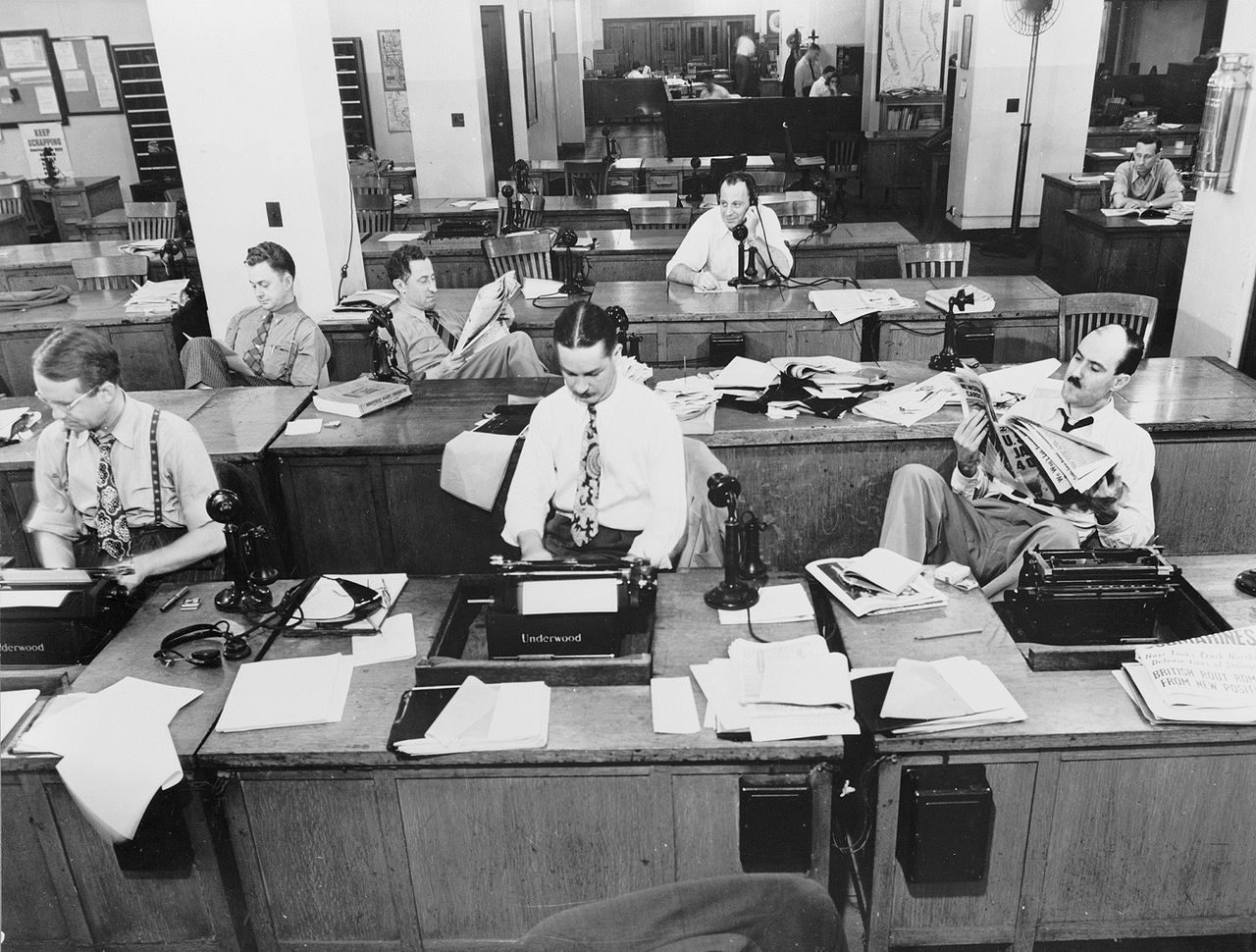

New York Times newsroom, September 1942. Library of Congress

These days, everyone not named Donald Trump adores newspapers.

According to a 2018 YouGov survey, more people trust the information in their local newspaper than any other media source. At 74 percent, newspapers earned three times the trust of news from social media networks. Presidential candidate Andrew Yang wants to subsidize them with a $1 billion “Local Journalism Fund.” Apple rolled out a “News+” subscription service intended to distribute them digitally. Hollywood keeps making hagiographies for print journalism like The Post and Spotlight. The Washington Post spent a small fortune on a Super Bowl ad in February to pat itself on the back for a journalism job well-done along with its self-serious slogan: “Democracy dies in darkness.”

The appeal is understandable. The United States needs clear-eyed, fearless reporting that is skeptical of its leaders, especially with Trump declaring news sources that expose his endless lies or stray from his official narratives “enemies of the people” or “fake news.”

But where to go? The internet is rife with bots, dummy websites, and misinformation; the constant mudslinging of social media is exhausting, and cable news channels like Fox and MSNBC often serve as thinly veiled public relations wings of the Republican and Democratic parties. In comparison, fussy old newspapers naturally emerge as our best hope for informing us about the world around us — a time-tested rock in an age of uncertainty.

But liberals’ rush to defend America’s papers can obscure a deeper truth: the free press isn’t as free as we’d like to believe. Fox News is half right when they say there’s a liberal bias in corporate media — more precisely, a neoliberal slant. That slant disempowers the working class by downplaying their agency, narrowing the range of acceptable political ideas to exclude the Left, and ensconcing the idea that our only power comes from our own wallet or the ballot box.

The newspaper industry is still dominated by profit-driven corporations who survive at the mercy of other businesses buying advertisements — or, as is increasingly the case, the whims of billionaire benefactors like Jeff Bezos. Journalists also rely on access to elites in government, business, and the entertainment world for stories, so it’s against their interest to anger those sources and risk losing that access.

Being beholden to powerful interests sometimes directly leads to blatant pay-for-play coverage, such as the way that billionaire Sheldon Adelson remade the Las Vegas Review-Journal to suit his conservative agenda after purchasing it in 2015. But the effect is often more subtle than that, coming from structural biases that favor the interests of the rich through conscious or unconscious strategic decisions.

Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman’s classic 1988 book Manufacturing Consent had a term for the kind of reporting that results from these inherent biases: “systematic propaganda.”

“The national media typically target and serve elite opinion, groups that, on the one hand, provide an optimal “profile” for advertising purposes, and, on the other, play a role in decision-making in the private and public spheres,” Chomsky and Herman wrote.

The national media would be failing to meet their elite audience’s needs if they did not present a tolerably realistic portrayal of the world. But their “societal purpose” also requires that the media’s interpretation of the world reflect the interests and concerns of the sellers, the buyers, and the governmental and private institutions dominated by these groups.

Ironically, Manufacturing Consent explains why Chomsky himself and other third political parties, activists, and dissidents have been so rarely quoted in mainstream political and news analysis over the last three decades. In my interview with the Intercept’s Jeremy Scahill last year, he noted that “Chomsky is perhaps the most famous living American dissident, and he is never invited [to talk to the media],” Scahill said.

Newspapers may crow about their commitment to “objectivity,” but their idea of balance is horizontal, not vertical, which boils down to giving equal space to the narrow political perspectives of elites.

There’s no better example of newspapers’ natural bias revealing themselves than Bernie Sanders’s first presidential campaign in 2016. Sanders represented a massive problem for the press: as a sitting US senator, he was an insider; but his democratic-socialist views and political independence meant newspapers wanted to treat him like a dangerously far-left outsider.

At first, the press reacted to his insurgent campaign with silence. He got so little ink compared to Trump and Hillary Clinton that it became a phenomenon deemed the “Bernie Blackout.” In an analysis for Harper’s in 2016, Thomas Frank noted that Hillary Clinton earned three times as much coverage in the mainstream media as Sanders from May to November 2015.

Once the chattering classes started talking about Sanders more, the coverage tended to be critical. Of two hundred Washington Post editorials and op-eds about Bernie published in early 2016, the negative (with headlines like “Nominating Sanders Would Be Insane”) outnumbered the positive roughly five to one, compared to a nearly fifty-fifty split for opinion pieces on Hillary Clinton. And as FAIR’s Adam Johnson noted, that total included sixteen negative Washington Post pieces in a single sixteen-hour period.

Sanders is now a frontrunner in the 2020 race, but the Post is still on the attack — running at least ten anti-Sanders op-eds over a two-week period starting March 18. And the gratuitous hit pieces keep coming, like Jennifer Rubin’s May 20 column: “Is Sanders past his sell-by date?”

Newspapers’ biases go way beyond electoral politics. Editors and journalists tend to view the economy and jobs through the eyes of bosses over their workers.

For instance, a 2015 University of Sheffield study of the UK’s newspaper coverage of the economy between 2007 and 2014 concluded that reporters overwhelmingly used neoliberal framing to describe the effect of the financial crisis or austerity measures. Ordinary people were described as consumers, not citizens, and what mattered most was their spending power and productivity. “Issues like health or poverty were sidelined,” the study noted, and economic recessions were treated as natural disasters outside of human control, not as calamities created by capitalist institutions.

There’s a reason why the daily business section prints stock market over unemployment or living-wage numbers. As Christopher R. Martin notes in No Longer Newsworthy, newspapers have all but abolished labor reporting over the last generation. What you get instead of stories about unions are ones that traffic in the Great Man theory of work. They valorize heroic CEOs that generate big profits for shareholders and render the rank and file invisible except when they’re laid off in massive numbers (judged to be good or bad depending on how Wall Street responds to it).

White-collar and corporate crime leads to much more human misery, disability, and death, and costs society more money than violent and property crime. But the face of crime in newspapers is overwhelmingly poor.

Here’s a particularly galling headline from a recent Chicago Tribune’s business section: “Ever have one of those days? Walgreens’ CEO lost $1.2 billion Tuesday.” It’s an eight-hundred-word article that discusses the pharmacy-store company’s stock prices but not the economic health of the basic Walgreens employee. Why lament the fact that a majority of the company’s 415,000 workers make less than $10 an hour when you can mourn the decline in wealth of CEO Stefano Pessina, whose fortune is still over $11 billion?

These institutional biases are baked into nearly every newspaper in the United States, from the New York Times to the Des Moines Register, but they’ve been normalized or obfuscated over time.

There are signs, however, that the status quo is changing. The internet has devastated newspapers’ ad revenue and more than one in five local papers have closed since 2004, according to a University of North Carolina report. Indeed, this is a tragedy that has resulted in less coverage of local politics and a less informed citizenry.

But the distinct upside of the destabilizing effects of the web and social media is that elite media gatekeepers’ power has been weakened. Sanders made an effort to bypass the hostile press and spread his democratic-socialist policies directly to voters through social media.

Social media and the web have also helped labor and activist groups organize better. The last few years have seen a number of large, left-wing protest movements like the Women’s March and Black Lives Matter and labor stoppages, including strikes by 373,000 teachers and educators in six red states. Democratic socialism’s rise and labor and protest movements’ resurgences have reached a critical mass — meaning newspapers have fewer excuses to avoid covering them.

The Washington Post is right that democracy dies in darkness — so maybe it’s time for some self-reflection. I suggest Bezos and company watch The Post again.

It’s a dramatized version of WaPo’s decision to publish the Pentagon Papers that many critics saw as a stirring ode to newspapers’ glory days. It “triumphs as an energizing call to arms against any political tyrant who’d deny journalists the right to speak truth to power,” gushed critic Peter Travers in Rolling Stone.

What’s lost in the praise is that The Post is also a story about how a powerful newspaper almost refuses to publish documents that expose the lies and cover-ups of the Vietnam War because of the pressures inherent to the corporate press. The wealthy heiress who runs the Post (Katharine Graham) almost caves to avoid pissing off nervous shareholders during the company’s stock market launch and because she’s close friends with one of the war criminals (Robert McNamara) who escalated the war in Vietnam. Behind the scenes, she also battles with Ben Bradlee, an editor who has a chummy relationship with JFK.

That Graham and the Washington Post made the right decision in 1971 doesn’t account for the countless other stories buried or mishandled by newspaper executives and editors over the last few generations because of those same pressures.

Through a different lens, The Post proves that liberals still wear rose-colored glasses when it comes to the shortcomings of corporate print journalism. Not that you’d hear that in a Super Bowl commercial.