Testaments Betrayed

How Yugoslavia's vibrant Marxist humanists morphed into right-wing nationalists.

View of Grbavica, a neighbourhood of Sarajevo, approximately 4 months after the signing of the Dayton Peace Accord that officially ended the war in Bosnia. Lt. Stacey Wyzowski / Wikimedia

Much has changed since Gerson Sher traveled to Yugoslavia to research his dissertation amid the political and intellectual ferment of the late 1960s. For one thing, the idiosyncratic country that captured his imagination no longer exists. Nor does Praxis, the group of Marxist humanist philosophers Sher studied. But this is not the only reason he responds warily to a request for an interview: “I am appalled,” he says, “that you should be interested in Praxis at this time.”

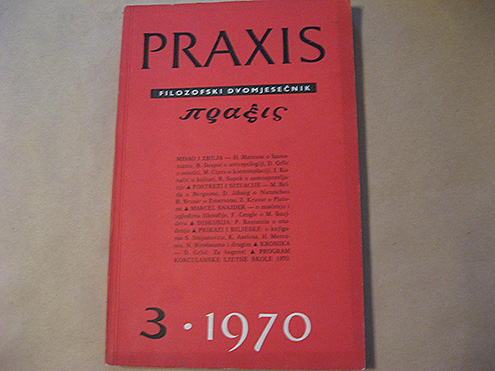

Why? After all, according to the Harvard political theorist Seyla Benhabib, “the name Praxis has a distinguished history. It was used by dissidents against Stalinism and identified with the project of democratic socialism.” Sher’s dissertation, later published as Praxis: Marxist Criticism and Dissent in Socialist Yugoslavia (Indiana, 1977), explored what seemed a promising strain of humanist thought emerging from the University of Zagreb and the University of Belgrade. In the 1960s and 1970s, a glittering roster of Western intellectuals attended the Praxis group’s yearly retreats on the Adriatic island of Korcula: Jürgen Habermas, A.J. Ayer, Norman Birnbaum, Lucien Goldmann, and Herbert Marcuse were just a few of those who gathered around the Yugoslav group and served on the editorial board of its eponymous journal. Strange, then, that today the term “Praxis” and the names of some of its leaders are just as often associated with the notoriously anti-humanist rhetoric of Serbian nationalism and the murderous politics of Slobodan Milosevic.

History, the Praxists urged, “is made neither by objective forces nor dialectical laws; it is made instead by people, who act to transform their world within the limits of historical possibilities.” So wrote Sher in 1977. In the precarious decade to follow, the Praxis philosophers would indeed transform their world. But the way they did so was not, at that time, imaginable to academics in the West. Who could have known that one of the Praxis philosophers would later become vice president of Milosevic’s party — and its chief ideologue during the Bosnian war? Or that another member, once a passionate critic of nationalism, would sign a 1996 petition calling for the Hague to drop war-crimes charges against the brutal Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic, whom the petition dubbed “the true leader of all Serbs”?

Not all of the Praxists followed their leaders down the dark road of Serbian nationalism. The Croatian members cleaved to their humanist principles through the bloodiest years of the Yugoslav wars. And in Serbia, some of the most courageous and lonely expressions of dissent have come from former Praxists and their students.

The fault lines along which not only Praxis but the Yugoslav nation would later splinter were invisible to the group’s foreign admirers back in the 1960s. After all, to progressives abroad, Tito’s Yugoslavia stood for something uniquely inspiring: Not only was it less authoritarian than the Eastern-bloc countries, but Tito had adopted a uniquely ambitious program of worker self-management that promised to help Yugoslavia realize the most utopian Marxist project any country had yet attempted. To the extent the Praxis group spoke of nationalism, it was to oppose it as an atavistic threat to the universalistic principles of humanism and Marxism. The region’s grim history and simmering internal rivalries were the last thing on anyone’s mind.

Norman Birnbaum, now a law professor at Georgetown University, explains, “When we went to Yugoslavia at that time, we did think the nationality question had been solved. It was the Titoist truce, or illusion, or parenthesis.” Croatian-born historian Branka Magas puts it differently. The Western leftists who took up with Praxis as late as the 1980s and early 1990s, she says, “never really saw Yugoslavia. They saw self-management. They only saw the country through the lens of what interested them.”

Looking back on Yugoslavia during the Tito years, writes Tim Judah in The Serbs: History, Myth, and the Destruction of Yugoslavia (Yale, 1997), one “cannot fail to be struck by just how inconsequential some of the great debates of the past have turned out to be.” Indeed, it might seem today that Marxist humanism and self-management were just a couple of blind alleys off the highway to Sarajevo. But when Praxis coalesced around these concerns in the 1960s, they looked for all the world like the yellow brick road to a utopia where democracy would at last nourish socialism. It was time for the communist bureaucracies that had ossified in Eastern Europe to give way, the Marxist humanists argued, and let a dynamic, participatory socialism flower.

At its inception, the philosophical journal Praxis was merely the successor to Pogledi, a political journal issued from Croatia’s capital, Zagreb, in the 1950s. Pogledi was a casualty of state interference: It lasted only three years. Chief among the defunct journal’s contributors had been the University of Zagreb sociologist Rudi Supek, who participated in the French Resistance as an emigre during World War II and later led an underground prisoners’ organization when he was interned at Buchenwald; and the University of Zagreb philosopher Gajo Petrovic, a Serb from Croatia who gravitated toward the early Marx, existentialism, and Heidegger. Birnbaum remembers, “Supek and Petrovic were impressive for their moral rigor, their utter disdain of careerism. They were people you loved to be around.” From the ashes of Pogledi, Supek, Petrovic, and their colleagues went on to start their summer school on Korcula in 1963 and a new journal, Praxis, in 1964. The group that formed around these ventures consisted of a close-knit circle of friends and colleagues — some from Supek’s and Petrovic’s departments at the University of Zagreb and another eight from the philosophy department at the University of Belgrade.

The philosophers published their new journal in a Serbo-Croat Yugoslav edition and in a multilingual international edition. And its editorial collective adopted an agenda that was more unified than anything Pogledi had ever set forth: The Praxis group advocated freedom of speech and of the press, and they believed that Stalinist authoritarianism had to be redressed in practice and rooted out of Marxist theory itself. To this end, they prescribed a return to Marx’s romantic early writings, particularly the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Marx’s more influential later work would emphasize the iron laws of historical determinism. But the 1844 Manuscripts waxed lyrical about the creative potential of human activity, through which man might realize his “species being.”

This orientation was hardly a Yugoslav invention. If anything, the Praxists took their cue from neighboring Hungary, where Georg Lukacs had amassed a following of like-minded dissidents. Like Lukacs, the Praxists were captivated by the early Marx’s theory of alienation. In an ordinary capitalist or a Stalinist socialist society, man was alienated from himself by the commodification of his labor and by the overweening power of a small, privileged class and its institutions. A utopian Marxist society, the Praxists imagined, would overcome that alienation; it would unleash human creativity — or “praxis” — by doing away with the ruling class through self-management. The workers would directly control not only their workplaces but also social and cultural institutions — even local political parties and governing bodies. The state, given enough time, would of its own accord “wither away,” just as Marx had predicted.

Yugoslavia, despite Tito’s bold initiatives, fell far short of this ideal. In Yugoslavia’s hybrid economy, the much-touted self-managing enterprises were exposed to market pressures, on the one hand, and capricious state control, on the other. Regional oligarchies took root: In the end, local power brokers manipulated and ignored workers’ councils in much the way managers do everywhere. But the Praxists saw these problems as evidence that self-management had not gone far enough. They were at once self-management’s most passionate exponents abroad and the Yugoslav system’s fiercest internal critics.

That Tito tolerated Praxis at all is remarkable. Virtually no other Communist country, with the possible exception of Hungary, allowed as much vocal dissent as Yugoslavia did in Tito’s day. But there were limits to Tito’s tolerance. At a philosophy faculty meeting in 1967, Ljubomir Tadic, a Praxis philosopher at the University of Belgrade, instigated a particularly perilous game of chicken with the authorities. In the antiauthoritarian spirit of Praxis, Tadic publicly criticized the constitutional provision that allowed Tito to remain in office for longer than his eight-year mandate. When the renegade professor came under government investigation, the faculty stood united behind him, and he was permitted to keep his job.

With the enthusiastic support of the Belgrade Praxists, student demonstrations convulsed the University of Belgrade in June 1968. The students protested their poor living conditions and demanded an end to authoritarianism, unemployment, and, for good measure, the Vietnam War. Local Serbian authorities urged Tito to send military troops onto the Belgrade campus. After all, it was that same summer that Soviet tanks would put an end to popular protests in Prague. But unlike his ham-fisted counterparts in Moscow, Tito deployed a feline cunning to dispense with his foes. In a televised appeal, he proclaimed himself deeply sympathetic to the activists’ concerns. In fact, he said, it was only Yugoslavia’s bureaucracy that stood in the way of the agenda he and the students shared. If the bureaucrats did not allow him to meet these students’ demands, he declared, he would resign. Of course, the demands were not met, and Tito did not resign. In fact, only two weeks after he gave this speech, he urged the University of Belgrade to dismiss its Praxis philosophers on the grounds that they were “corrupting” students. The plight of those philosophers, known as the Belgrade 8, became a matter of international concern.

That summer was particularly memorable at Korcula. Richard Bernstein, now a political philosopher at the New School for Social Research, recalls, “Everybody who was a significant leftist, in the East or in the West, came to the 1968 meeting. All the leaders of the student movements in Germany, Eastern Europe, and the United States were there.” But even as the editorial boards of Praxis and theNew Left Review sunned themselves on the beaches of Korcula, the Belgrade 8 held on to their jobs by a slender thread.

Throughout this period, the Yugoslav government was undergoing a subtle but significant shift. From the end of World War II until 1966, Tito’s main challenge had been to consolidate his unwieldy multinational state. Even within his inner circle, debates raged over whether Yugoslavia’s six constituent republics — Bosnia, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia — should be granted greater autonomy or tethered more firmly to a central authority. History had taught that in the Balkans one ignored these questions at one’s peril: The short-lived first Yugoslavia (1918–1941) opted for a rigid centralism; the state was governed by a Serbian monarchy and the country’s military, culture, and politics were overwhelmingly dominated by Serbs. Throughout those years of oppression, Croatia smoldered with resentments — and during World War II, the latent animosities exploded. Under fascist leadership, Croatia pursued a genocidal campaign against Serbs as well as Jews. The savagery of the killings shocked even German SS officers stationed in the Balkans.

With this history in mind, Tito’s regime walked a fine line between a strong central state, which was by and large favored by Serbs, and a loose confederation of republics, which was generally favored by Croats and Slovenes. Centralism prevailed in the early postwar years, but momentum started to build in the other direction in the mid-1960s. A new set of constitutional arrangements slowly took shape, offering greater autonomy to each republic. But this did not appease those who favored a looser confederation. A Croatian nationalist movement was born of the sentiment that the reforms of the late 1960s had not gone far enough. Among the activists’ grievances was that Croatia, which was more industrialized and generally wealthier than Serbia, Montenegro, and Macedonia, carried more than its share of Yugoslavia’s economic burden. Extremists advocated Croatian secession. Students, intellectuals, and even local Communist authorities gathered around a Croatian cultural society called Matica Hrvatska until Tito disbanded the group, purged its participants from political life, and arrested student leaders.

Watching the growing nationalist militancy of their fellow Croatian academics, the Zagreb Praxists were horrified. And for this very reason, Tito suddenly found these Praxists indispensable: After all, nationalism was a greater threat to the fragile nation than Marxist critique would ever be, and the members of the Zagreb group were outspoken and eloquent against the greater evil. So even while the Belgrade Praxists, who were associated with student unrest, appealed to the international community for protection, their Zagreb counterparts, who were associated with the fight against Croatian nationalism, continued their work in peace.

Against this backdrop, Praxis published a special issue on nationalism in 1968. It was the high tide of the journal’s resistance to the politics of ethnic identity. In one essay, Ljubomir Tadic, himself a Bosnian Serb, argued that nationalism contradicted the very notion of universal humanity. In place of justice, the nationalist asserts the right of the strong to dominate the weak and the power of violence to resolve conflict. “One quickly forgets,” Tadic wrote, “that Serbian and Croatian nationalisms … have remained militant, despotic ideologies that lack political and cultural creativity in all their forms.” Where social justice and political liberty were in decline, Tadic theorized, nationalism would emerge ascendant. But socialist Yugoslavia had demonstrated “the superiority of proletarian class-consciousness over nationalist consciousness, [and] the advantage of democratic unity over imposed unity or forced disintegration.”

Other contributors were equally impassioned. Danko Grlic, a Croat, vividly evoked the irrationality of nationalism. Once unleashed, he warned, it would be impervious to logic: “You do not reason or theorize about the nation; for the nation you only struggle and die; you love the nation as the flesh of your flesh, as the essence of your being, drinking it with your mother’s milk; it is body and blood …”

Otvoreni Magazine.

The allegiance of Praxis to a united Yugoslavia seemed clear enough. But given the ever present threat of government censorship, there was little that Yugoslav intellectuals published in those years that was completely transparent. The Zagreb philosopher Zarko Puhovski, the youngest Praxist by about twenty years, says that the group’s disputes over politics and ideology were often disguised as conversations about less controversial questions of aesthetics or ontology. “One kind of debate functioned as a replacement for other kinds of debate,” he recalls.

This was particularly evident when Puhovski himself edited a special issue of Praxis in 1973. He received a submission from the well-known Serbian novelist Dobrica Cosic. It was a short piece that argued that true socialism was not possible in an unenlightened society and that faith in the people — of which Cosic claimed to have little — was the “last refuge for our historically defeated hopes.” Which people and what hopes? The article did not specify. But Puhovski detected a disturbing nationalist message all the same. Nor was he impressed with the article’s argument or its rigor: “I had the junior approach of believing that philosophy and sociology were specialized fields,” he recounts with a touch of sarcasm. “I didn’t think Cosic’s piece was up to the level. It was bad nationalist propaganda.” He turned it down.

His elders chided him that he simply did not understand how important a figure Cosic was. Cosic was best known as the author of Yugoslavia’s most celebrated Partisan war novel, Far Away Is the Sun (1950), in which a company of Partisan soldiers affirm their commitment to Yugoslavism and Communism by executing a Serbian nationalist in their midst. But Cosic’s colors had begun to change: In 1968 he had been expelled from the Central Committee for accusing the regime of fostering Albanian separatism in Kosovo. Even so, he would not be widely considered a nationalist writer until the late 1970s and early 1980s, when he published a series of novels that explicitly addressed Serbian history and grievances. At that time, he cut such a distinguished figure in Belgrade that he was frequently called the father of the Serbian nation.

As the 1973 issue of Praxis neared press time, Puhovski was on his own: the editorial board split seven to one in Cosic’s favor.

The appearance of nationalist tensions within the Praxis group was a harbinger of tensions that would soon spread across the country. Years later, when war raged in Kosovo, American newspapers would plug 1989, the year Milosevic revoked Kosovo’s autonomy, as the beginning of the end of Yugoslavia. But many Serbs would say the country’s fate was sealed as early as 1974. That was the year a controversial revision of the Yugoslav constitution went into effect, devolving broader powers than ever before to the six republics and granting full autonomy to two provinces within the republic of Serbia: Kosovo and Vojvodina. Since the Serbs were scattered across the republics — more than a million lived in Bosnia and at least 500,000 in Croatia — these constitutional reforms were to feed a growing sense of grievance among the Serbs.

In Belgrade, two strains of protest greeted the 1974 constitution. A student strike seized the university campus in the name of Marxist ideals: Where, the students asked, were the pan-Yugoslav interests of the working class reflected in this new constitution? The students feared that the reform, with its emphasis on divisions among the republics, would weaken Yugoslavia’s socialist unity by opening a Pandora’s box of ethnic grievances and demands. As if to prove the students right, other critics of the constitution, including Dobrica Cosic, protested that it unfairly disempowered the Serbs.

In subsequent years, Serbian nationalists would bitterly complain that Tito’s policy had been “A weak Serbia is a strong Yugoslavia.” But why shouldn’t it have been? Of the country’s six official nations, the Serbs were far and away the most populous, outnumbering the Croats two to one. If multinational Yugoslavia’s culture and politics were to be governed by majority rule, the country would not survive: The non-Serb populations had strongly developed national identities and long, distinct histories of their own. Not only that, but they occupied more compact territories than did the Serbs. If they felt overly dominated, they could be tempted to secede. So Tito restrained the potentially overweening influence of the Serbs by dividing Yugoslavia into territorial units and constantly readjusting the internal balance of power.

Today, some critics blame the constitution of 1974 for the growth of nationalist movements in Croatia and Slovenia. More likely, it was a response to the nationalist movements that were already stirring. In any case, the most scathing criticism was leveled by the Serb nationalists: The new constitution rested on a double standard. If Yugoslavia’s units of political participation were its ethnic groups, or “constituent nations,” then the Serbs in Bosnia and Croatia, who were represented by Muslim and Croatian leadership, respectively, went unrepresented. But if the units were territorial, then why was Serbia the only republic whose territory included autonomous provinces over which it had little control?

The truth was very simple: in multinational Yugoslavia, Tito had deliberately redistributed power from the strong to the weak. And if his belief really was that a strong Yugoslavia required a weak Serbia, perhaps he was not mistaken. Much later, in 1989, when Milosevic finally did enforce Serbian control of its provinces, Serbia emerged strong — and Yugoslavia fell to pieces. The terrible irony in all of this is that the geographically dispersed Serbs may have benefited more than anyone from the years of Serbia’s weakness. For of all the Yugoslav nations, only the Serbs needed a unified Yugoslavia more than it needed them.

If 1974 marked the beginning of Yugoslavia’s national crisis, it also augured the end of the Praxis group’s legal existence. Tito purged the Belgrade 8 from the university the following year. The six-year-long struggle between the state and the professors had simply exhausted itself. Not only were the Belgrade 8 suspended from teaching, but the journal Praxis was also banned. This time, the protests of American academics (including Daniel Bell, Noam Chomsky, and Stanley Hoffman) fell on deaf ears.

For more than a decade, the Belgrade 8 — Mihailo Markovic, Svetozar Stojanovic, Ljubomir Tadic, Zagorka Golubovic, Dragoljub Micunovic, Miladin Zivotic, Nebojsa Popov, and Trivo Indjic — wandered the globe, accepting visiting professorships abroad and meeting secretly in Belgrade. Only Indjic accepted the government’s offer of a low-profile post at an institute. The others insisted on nothing less than a full return to the University of Belgrade, which was not forthcoming. Markovic, the group’s best-known member abroad, took a part-time philosophy post at the University of Pennsylvania. Stojanovic taught at Berkeley and at the University of Kansas. Meanwhile, in Zagreb, the situation was slightly less dire. “There were pressures,” remembers Zarko Puhovski. “I couldn’t publish for two years. But it was nothing remotely like the situation in Belgrade.”

The rest of the 1970s and the early 1980s were disappointing years for the Belgrade 8. They organized what they called the Free University, which mostly consisted of seminars held in private homes, but they could not advertise these meetings, and they were constantly on guard for police interruption. At least one Free University session convened at the novelist Dobrica Cosic’s house. Neither a Marxist nor a philosopher, Cosic was a personal friend and shadowy influence on the Praxis group although never an actual member. In the 1980s, his ties to Praxis pulled tighter; but to what extent the Praxists already shared his incipient nationalism remains a mystery. Cosic collaborated with Tadic on two projects in the early 1980s: One, a proposed journal that would criticize bureaucracy and champion freedom of expression, was immediately suppressed by the government; the other, a petition against censorship laws, was also swiftly defeated. The government press denounced Cosic and his Praxis friends as “hardened nationalists and open advocates of a multi-party system,” but the group continued to convene as a committee to promote freedom of expression.

Meanwhile, Yugoslavia had gone into a deep economic slump: Foreign debt had skyrocketed to $19 billion, unemployment was up to 17.5 percent, inflation topped 120 percent, and the standard of living precipitously declined. The Yugoslav experiment no longer enjoyed the prestige in the West it once had. And in 1980, Tito’s death left the rickety multinational structure leaderless and volatile.

In Kosovo, the Albanian majority, which was largely poor, uneducated, and powerless, had grown restive. The Albanians had never had the status of Yugoslavia’s other “constituent nations”: Tito’s regime reasoned that because there was an Albanian homeland outside Yugoslavia, they should be considered a “national minority” instead. The Kosovars countered that fully 40 percent of the world’s Albanian population resided in Yugoslavia. Demonstrations swept the province in 1981, demanding first and foremost that Kosovo be granted the status of a republic, including the right to secede. The movement reached a fever pitch: Serbs and Montenegrins were attacked and threatened, Orthodox holy sites were desecrated, and some activists began to call for secession and union with Albania. Yugoslav police squelched the riots, imposing a state of martial law whose severity scandalized Croatian and Slovenian intellectuals. A great many Albanians languished as political prisoners in Kosovo’s jails. Meanwhile, the province’s Serb minority felt increasingly scapegoated and threatened.

Wikimedia

With Praxis driven underground, the Korcula summer school, needless to say, was long since over. But something new had begun: The Inter-University Center, in the majestic Croatian city of Dubrovnik, was an international institution that sponsored conferences and short courses run by intellectuals from all over the world. Because it was not managed by Yugoslavs, it was relatively free from government interference. Once again, prominent Western leftists crossed the Adriatic. One of the Praxists approached Jürgen Habermas about teaching a course in Dubrovnik as a way of reviving the spirit of Korcula. The revered German philosopher and heir to the Frankfurt School returned to Yugoslavia with Richard Bernstein to co-teach a course in 1979. The Praxis group, however dispirited, reconvened in Dubrovnik, where it encountered a new set of sympathetic leftists from the West. Seyla Benhabib remembers that she went to Dubrovnik in 1979 in order to get to know Bernstein and Habermas. That she also encountered the Praxis group was merely a happy accident. All she knew about the Praxists’ activities at that time was that “they had been expelled and gone into the opposition.”

It was in Dubrovnik that Habermas, Bernstein, and German philosopher Albrecht Wellmer hatched a plan to revive the Praxis journal that had so interested them in the 1960s. To provide the disfranchised dissidents with a new, international forum for their work could only do the cause of democratic socialism good, the Western philosophers figured. Together with Markovic and Stojanovic, they launched Praxis International in 1981.

The new journal attempted to pick up where the old one had left off but with a less Yugoslav focus: It included many Praxis-style theoretical essays on Marxism and, as the 1980s wore on, it covered Eastern European countries in transition. Produced mostly in the United States and published by Blackwell, the journal was far more eclectic than the first Praxis had been: Contributions in the late 1980s and early 1990s addressed the political thought of Cornel West, the relationship between feminism and socialism, and other topics of general interest to left-leaning intellectuals.

By this time, Mihailo Markovic was clearly the Yugoslav group’s leader, and he came to play a crucial role in the revived journal. A fluent English speaker, he was gregarious, cosmopolitan, and urbane. Both his anti-Stalinist and his antifascist credentials were impeccable: He had fought in Tito’s Partisan army during World War II and prided himself on extending aid to Yugoslav Jews. In his philosophical work, Markovic emphasized Marx’s commitment to human dignity, freedom, and self-realization.

Bernstein and Markovic became close friends over the course of their joint stewardship of the journal. David Crocker, a philosopher at the University of Maryland and the author of Praxis and Democratic Socialism: The Critical Social Theory of Markovic and Stojanovic (1983), also came to consider Markovic a personal friend. Only Andrew Arato, a professor of sociology at the New School, had an instinctive dislike for the elder Serb. Markovic reminded him of an apparatchik. “He was clearly an authoritarian personality. I remember once he kept me outside in a snowstorm for forty minutes, trying to convince me that political parties were a bad thing,” Arato says with a laugh. “He wouldn’t let me in the restaurant — as if by the sheer force of his personality, he would persuade me that democracy didn’t need to work through parties.” Other Belgrade Praxists, he says, were very much in Markovic’s thrall. “But when they were not together with Mihailo, one could talk to them about everything. They were more flexible and more Western.”

Of the Zagreb Praxists, very few of the old-timers were enthusiastic about the Belgrade group’s new publishing venture. Zagreb’s elder statesmen, Rudi Supek and Gajo Petrovic, attended the first meeting. Supek was amenable to the new journal; but Petrovic felt strongly that the name Praxis should not be used. Praxis, Petrovic argued, connoted a joint Belgrade-Zagreb publication, whose international component came at the Yugoslavs’ invitation. This new journal, however, was to be published in English and dominated by Belgraders and Americans. It was international before it was Yugoslav, and for this reason, he insisted, it should have a new name and a new identity. Perhaps Petrovic also sensed that his Belgrade colleagues had changed and that political consensus was a thing of the past. If he did, he did not say so.

Praxis International‘s American editors were not particularly perturbed that, with the exception of Supek, they had lost the Zagreb contingent. Says Seyla Benhabib, “The question of ethnicity was irrelevant. They were all Yugoslavs. To us outsiders, it wasn’t even like asking, ‘Are you Italian American or Irish American?’ It was more like asking, ‘Are you Bavarian or from Berlin?'”

Yugoslavia’s six republics and two autonomous provinces were already on a collision course by the mid-1980s, but even the most astute Western observers did not perceive what lay ahead. The most visible sign of trouble was in Kosovo, where martial law had only stoked the flames of ethnic strife. The Serb minority clamored for Belgrade’s attention: In 1985 Kosovo’s Serbs sent a petition to the central government, claiming that Serbs had been raped, murdered, and driven from their homes by the province’s ethnic Albanians. Couldn’t Belgrade do something?

To what extent Kosovo’s Serbs were persecuted remains debatable. To be sure, they were outnumbered, and there is no reason to doubt that they faced threats, vandalism, harassment, and even the occasional act of criminal violence from an Albanian majority that deeply resented Slavic rule. But to Yugoslavs outside Serbia, complaints of anti-Serb discrimination in Kosovo were incomprehensible. After all, Serbs were hardly an oppressed group in the nation as a whole, whereas the Albanians formed something of an underclass.

So it was a surprise to many of the Belgrade Praxists’ admirers when three key members of the group — Markovic, Tadic, and Zagorka Golubovic — signed a 1986 petition in support of the Kosovo Serbs. Cosic also signed. It was not just that the petition painted a florid picture of Serbian suffering in the southern province. It was also that the signatories obliquely urged the government to revoke Kosovo’s autonomous status — something Serbian nationalists had been pushing the parliament to do. After all, the petitioners reasoned, with its “unselfish” aid to the impoverished province, Serbia had amply demonstrated that it took the Albanians’ interests to heart. Ominously, the petition’s authors intoned: “Genocide [against Kosovo’s Serbs] cannot be prevented by … [the] politics of gradual surrender of Kosovo … to Albania: the unsigned capitulation which leads to a politics of national treason.”

When Branka Magas, a historian who had emigrated from Yugoslavia in 1961, saw the petition, she was alarmed. She republished it, along with her own devastating critique, in the British journal Labour Focus on Eastern Europe. Magas’s essay was called “The End of an Era,” and she signed it with an assumed name that disguised her Croatian background. “This unexpected, indeed astonishing, alignment of Praxis editors with nationalism,” she wrote, “has aroused considerable dismay among their friends and sympathizers, for it delineates a complete break with the political and philosophical tradition represented by the journal.”

According to Magas, the editors of Labour Focus were skeptical. Mihailo Markovic’s reputation as a humanist preceded him. Could there be some mistake? The editors sent Magas’s piece to the Praxists for a response. Markovic, Tadic, and Golubovic were outraged. They had not abandoned their ideals, they wrote. They pointed out that they continued to publish Praxis International, a journal dedicated to democratic socialism, and that they served on Cosic’s committee for freedom of expression. They insisted that they spoke out against repression, no matter what the victims’ ethnic background: “Are we nationalists because we also write on national issues (which are very acute in Yugoslavia now), or because we, being Serbs, also defend Serbian victims of repression?”

To Magas, this exchange sent up a red flag. The rhetoric of Serbian victimhood, she noticed, was disturbingly similar to the rhetoric of a document that had recently been leaked to the Yugoslav press: the draft Memorandum of the influential Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences. The Memorandum was what the New York Times reporter Roger Cohen has called “an incendiary catalog of Serbian resentments and ambitions.” Its authors claimed that Serbs outside Serbia were in grave danger, that Yugoslavia was disintegrating, and that despite Serbia’s superior contribution to the winning side in World War II, its people were divided and underrepresented in post-1974 Yugoslavia. Many analysts have described the seventy-four-page document as the catalyst for Milosevic’s rise to power: It provided the conceptual blueprint for a Greater Serbia.

Magas later discovered that one of its authors was Mihailo Markovic.

In 1989, Seyla Benhabib took over the American editorship of Praxis International. At the time, she knew that conflict was brewing over Kosovo, but she did not yet understand its history or its dimensions. Her Praxis colleagues were little help. It was curious, she thought, that Svetozar Stojanovic, her Yugoslav co-editor, never wrote about recent developments in his own country.

Virtually all of Praxis’s Western collaborators remember Stojanovic as the most ideologically flexible of the Belgrade group. While Markovic cleaved to Marx’s 1844 Manuscripts, Stojanovic explored the possibility of a limited free market. He was the only Praxist seriously to investigate liberalism, and in a 1971 Praxis essay, he had dared to criticize Tito as a “charismatic leader.” Remembers Arato, “Stojanovic was more talented than Markovic, and Markovic was the boss.”

But when Benhabib brought up Kosovo in 1989, Stojanovic seemed annoyed and stunned. “Why do you want to know about Kosovo?” he asked. Benhabib replied, “There is a conflict there, and we don’t understand what that conflict is about.” Said Stojanovic, “Have we ever written about the Palestinian conflict in Praxis?” It was Benhabib’s turn to be uncomfortable. “Sveta,” she remembers saying, “what are you talking about?”

“Well, you know,” he reasoned, “a lot of our editorial board members are Jewish. There are just some issues we don’t touch.”

But, Benhabib protested, Praxis International did not avoid the Palestinian conflict because some of its editors were Jewish. It did so because the Middle East did not fall within its purview. Questions of nationality in Marxist countries, on the other hand, were obviously germane. Stojanovic relented. However, Benhabib notes, “When the article about Kosovo was written, Sveta, who was a moderate man, did not write it himself. It was Mihailo.”

Publishing Markovic’s Kosovo article, Benhabib says now, is the one editorial decision she truly regrets. The piece, which appeared in 1990, begins in an eminently reasonable tone. Nationalists on both sides of this debate, Markovic declared, have failed to listen to each other’s arguments. It was time to evaluate the facts.

The Albanians, Markovic calmly explained, are a backward, clannish people who have proven incapable of lifting themselves from poverty. The other Yugoslav republics have poured endless funds into Kosovo, but without results. The reason for this is both simple and sinister: Albanian nationalists have adopted a rapid birthrate as a demographic weapon against the Serbs. As a result of this scheme and of fiscal mismanagement by corrupt Albanian leaders, there are simply too many Kosovar mouths to feed. Compounding these economic problems is an ideological rift. The ethnic Albanians did not fight alongside the Yugoslav Partisans in World War II; for this reason, Markovic lamented, the populace never accepted the socialist revolution, and worse, it nurtures fascist tendencies left over from the Axis occupation.

But the most incredible piece of Markovic’s argument was yet to come. It might seem, Markovic mused, that the Albanians are just a small, poor, oppressed minority. But the truth is that throughout history the Albanians have had great powers on their side, while Serbia limped along on her own two feet. And just who were the Kosovo Albanians’ powerful protectors? The Ottoman Empire, Austria-Hungary, Italy, the Vatican, Great Britain, the Comintern, the United States, Pan-Islamic fundamentalism, Albania, and a cabal of bureaucrats in the Yugoslav government.

Some extreme solutions might suggest themselves, Markovic noted: violent police repression and compulsory family planning, for instance, or a partition and “exchange of population” that would leave the mineral-rich north of Kosovo to Serbia and the rest to Albania. But Markovic drew back from these possibilities. He proposed instead that autonomy be maintained, that investment in the province be scaled back, and that family planning be instituted “in a gentle and psychologically acceptable way, and by the Albanians themselves, using primarily educational means.”

In today’s light, the article is chilling. Benhabib is most struck now by the passage about the Albanians’ birthrate and their subsequent abject poverty. “This is cliche neofascist thinking, racist thinking about an oppressed group. You will find racists everywhere saying the same thing.” But back in 1990, the alarm bells somehow failed to sound. Benhabib knew very little about Kosovo, and to find out more, she had asked Stojanovic to commission a piece.

“Sometimes I felt like webs were being spun around me,” Benhabib says now. Not long after Markovic’s article appeared, Yugoslavia began its bloody disintegration. In 1991, Slovenia and then Croatia declared independence, touching off the Serbo-Croat war. Benhabib was in Frankfurt then, and people started approaching her about her colleague Markovic, who by this time was vice president and ideologue of Milosevic’s socialist party. “We’d run into individuals who would say, ‘Are you aware of what you are doing?'” she recalls. But it was after Bosnia ignited in 1992 that Benhabib became really uncomfortable. “We were being instrumentalized for prestige and credit,” she now believes. The last straw was an interview Markovic gave the New York Times in August 1992: “I don’t understand why there is so much opposition to cantonization,” he told the reporter, regarding the partition of Bosnia. “The alternative is creation of a Muslim state in the heart of Europe. Perhaps the Americans want to support this. … But we find this very disturbing.”

By 1993, Benhabib says, “we found that the situation had gotten too dirty, morally and politically.” The only way out was to stop publishing the journal and to cut ties with Stojanovic and Markovic. Praxis International published its last issue, “The Rise and Fall of Yugoslavia: Stations of a European Tragedy,” in January 1994; it included Slovenian, Croatian, and Serbian perspectives on Yugoslavia’s disintegration. Richard Bernstein’s friendship with Markovic was shattered by the Bosnian war. As for Benhabib, she has not kept in touch with Markovic or Stojanovic: Since the breakup, she says, “I have an aversion to following their careers.”

If Mihailo Markovic was not who his Western friends and collaborators had thought he was, who was he? Did he jettison his humanist beliefs to cozy up to a new regime? Or had he been a wolf in sheep’s clothing all along?

“Many people have read Markovic as being a cynic and a betrayer of Praxis,” says Bernstein. But in Markovic’s distorted vision, Bernstein suspects, “Serbia represented the progressive element of Yugoslav society” — the element bent on keeping Yugoslavia united and on preserving its socialist structure. Over time, he lost all perspective. “That’s the tragedy of Mihailo Markovic,” says Bernstein. “Instead of seeing the dark and ugly side of Serbian nationalism, he committed himself to it.”

The full measure of that commitment was apparent when Markovic became the vice-president of Milosevic’s party in 1991. David Crocker saw his old friend at a conference in Africa that year. Why, Crocker asked, had he joined the Serbian government? The philosopher’s answer was simple: “I got involved in politics to save the Serbs in eastern Croatia.” Otherwise, Markovic claimed, “they will be slaughtered.”

What on earth had made him think such a thing? But he was not alone. By 1992, the terms of political debate in Yugoslavia had undergone a dramatic shift. No longer was it a question of exactly how tightly the six republics and two autonomous provinces should be yoked to Belgrade’s central authority. As Communism crumbled across the former Eastern bloc, the Yugoslavs began to revive their own pre-Communist paradigms. But in Yugoslavia, these paradigms were extreme and unworkable, drawing on the country’s ugliest memories and worst fears: a Serb-dominated unitary state, which non-Serbs remembered bitterly from the first Yugoslavia; and the fratricidal killing fields of World War II, in which Serbs were overwhelmingly victimized. It seemed increasingly impossible for the country either to stay together in multinational form or to break apart without apocalyptic destruction.

Looking back now on the 1968 nationalism issue of Praxis, what appeared to be an antinationalist consensus starts to take a more ambiguous shape. Both the Serbs and the Croats repudiated the then-ascendant Croatian nationalist movement and supported the continuance of a united Yugoslavia. For the Croats, this stance was explicitly opposed to that of Croatian nationalism. But for the Serbs, the position was compatible with both a principled anti-nationalism and their own national interest: After all, Yugoslavia was really the only viable option for keeping the Serbs in one state. This is to say not that Markovic, Tadic, and the others were hoping to create a Greater Serbia back in 1968 — but that they didn’t need such a hope. Yugoslavia was perfectly comfortable. The Croats may have seriously grappled with the issues of ethnicity and nation in Yugoslavia in 1968. But the Serbs who blithely upheld Yugoslavism did so with all the arrogance, however well intentioned, of any majority.

Furthermore, whatever else the Praxists were, they were Marxists. In Croatia, to go on being a Marxist — or a Yugoslavist — placed one in opposition to the right-wing nationalist regime of Franjo Tudjman. And indeed, many of the Croatian Praxists have remained strong supporters of human rights: Zarko Puhovski, who is now vice-president of Croatia’s Helsinki Committee on Human Rights, has raised his voice courageously against the Croatian army’s ethnic-cleansing campaigns. And the economist Branko Horvat ran for president in 1992 on an antiwar, anti-authoritarian platform.

But for the Serb Praxists, the situation was different: To continue to support the country’s socialist forces was to ally oneself with Milosevic’s government, and to oppose Milosevic, it seemed, was to oppose what was left of Yugoslav communism. “His world fell apart,” Benhabib says of Markovic. “Liberalism was unacceptable. He did not want free-market capitalism.” Certainly, the new opposition parties, most of which were not only nationalist but also right wing or royalist, would not be acceptable to a Communist of Markovic’s generation. He apparently decided that Milosevic represented the future of Yugoslav socialism. After all, Milosevic had inherited the Communist Party apparatus, and his governing socialist party was among the last ones standing in Eastern Europe. Of course, Milosevic had mixed that deadliest of cocktails: socialism and nationalism. Markovic became one of the regime’s most outspoken and unrepentant apologists. And then, in 1995, he was purged from power — the government, it seems, had come to see his nationalist views as too extreme.

Of the Belgrade 8, none disgraced himself as thoroughly as Markovic, but there can be no question that nationalism captured the hearts and minds of many other Praxists. Consider the case of Svetozar Stojanovic and his ally, Dobrica Cosic.

In his 1997 book, The Fall of Yugoslavia: Why Communism Failed, Stojanovic wrote that the revolution in his thinking occurred in 1990, when mass graves from Jasenovac, Croatia’s World War II-era concentration camp, were disinterred for reburial. Stojanovic found himself confronted by his children’s anger: He had never talked to them about Jasenovac before. After all, such memories were suppressed during the Tito years. From that moment on, Stojanovic declared, he decided that his political work should be dedicated to the memory of Jasenovac.

Stojanovic’s political career would rise in tandem with that of his close friend, Cosic. In 1992, Milosevic appointed Cosic to a figurehead presidency of the rump Yugoslavia, and Cosic brought Stojanovic in as his top advisor. Many observers inside and outside Yugoslavia hoped that the presence of such reputable, if openly nationalist, figures marked a change of political course. Instead, it bought Milosevic a year of improved public relations abroad, while within the government, the moderates’ hands were tied.

In his book, Stojanovic condemns the Milosevic regime’s criminal activity on nationalist grounds: If one shares in collective pride, he reasons, one must also share in collective shame. And he claims that Cosic protested Milosevic’s deployment of brutal paramilitary formations in Croatia and Bosnia. At the same time, however, Stojanovic and Cosic did support Milosevic’s territorial aims. Yugoslavia could not be dismembered along the frontiers of its onetime republics, Stojanovic and Cosic argued. A “deeper map,” they believed, lay submerged beneath the map of Tito’s Yugoslavia; and this true map would account for the swaths of Croatian and Bosnian land that had been populated by Serbs for hundreds of years.

Cosic and Stojanovic were open to various solutions: Croatian independence might have been acceptable, Stojanovic implies, if Croatia had been willing to guarantee substantial autonomy to its Serb-populated territories. In practice, critics would object, such solutions were untenable. There would be autonomy for the Serbs in Croatia; and within that autonomy, should there be autonomy for the Croats in Serbian Croatia? And what, then, of the Serbs in Croatian Serbian Croatia? It is tempting to see this line of reasoning, which leads ineluctably to a reductio ad infinitum, as a sophistic device whose real purpose was to force Yugoslavia’s reintegration on Serbian terms.

Cosic’s presidency lasted only a year, and when he was ousted in 1993, Stojanovic left politics as well. Six years later, in the eerie silence following the Kosovo war, the Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences reconvened to consider the Serbian national question. At the June 1999 meeting, Cosic spoke at length of the ruin suffered by the Serb nation. “I appeal to Slobodan Milosevic’s patriotic consciousness and civic responsibility to resign in order for indispensable changes in Serbia and the federal state to begin,” he concluded.

Markovic took a harder line: “Our tragedy lies not in the fact that this or that person was head of the state. Our tragedy lies in the fact that the great powers have decided to destroy our country.”

Stevan Kragujevic / Wikimedia

Although only Stojanovic and Markovic served in the government, most of the Belgrade 8 have been politically active in the 1990s, and only a few have explicitly opposed the politics of Serbian nationalism. Ljubomir Tadic and Dragoljub Micunovic formed Serbia’s first democratic opposition party, the DS, in 1990. Although its founders’ ties to Praxis gave it the reputation of being the left wing of Serbia’s movement for liberal democracy, the DS established strategic alliances with parties on its right, including royalists and hard-line nationalists. The party’s leaders explained that these compromises allowed them to make a credible showing in parliamentary elections. But the conversion of Tadic, at least, to nationalism nevertheless seemed complete. He lent his uncritical support to the Bosnian Serbs, even meeting personally with their leader, Radovan Karadzic. With Markovic, Tadic signed a 1996 petition urging The Hague to drop its charges against Karadzic, “the true leader of all Serbs.” This was a remarkable act for a man who had written so eloquently in 1968 about nationalisms as “militant, despotic ideologies.” Gerson Sher, who remembers Tadic’s 1967 book, Order and Freedom, as a “masterpiece” of humanist thought, says ruefully, “Tadic is the greatest mystery of them all.”

Tadic’s colleague in the DS, Micunovic, maintained a more moderate reputation. He remained visible in public life until his former student Zoran Djindjic ousted him from the DS leadership in 1994. Djindjic, who also studied with Habermas and contributed to Praxis International, is today a presidential hopeful and favorite in the West. Micunovic now heads a pro-democracy nongovernmental organization. David Crocker, who saw him 1998, recalls, “He seemed a man who had given up in despair. The opposition had fragmented, nothing had come of it, and Milosevic was more powerful than ever.”

It is typical of recent Serbian politics that those Praxists who sought power were the ones who differed least with the ruling regime. Other Belgrade Praxists kept a greater distance from politics but continued to agitate for a genuinely democratic future. It was a member of the Belgrade 8 — Nebojsa Popov — who co-founded one of Serbia’s most principled and least popular parties, the Civic Alliance of Serbia, in 1991. Among its stated aims was “to overcome nationalist and class collectivism.” As the little brother of the two largest opposition parties, the Civic Alliance joined the Zajedno coalition that led protests at the University of Belgrade in 1996 and 1997. In one of the more surreal scenes to emerge from 1990s Belgrade, Popov appeared on Nikola Pasic Square with a pot of beans in February 1997. He and his colleagues were cooking beans for “all those hungry for freedom, truth, and democracy.” They pledged to continue “beaning” for 330 days or until Milosevic was deposed.

Among Popov’s allies are members of another Praxis offshoot: the Belgrade Circle, a small nongovernmental organization. Its president, Obrad Savic, was one of the students the Praxists led in the protests of 1968. Savic has been unsparing in his criticism of Markovic and Tadic’s turn to nationalism; in return, Tadic has denounced him as the founder of “anti-Serb mondialism.”

Some of the same people who were once drawn to Praxis and Praxis International — Habermas, Richard Rorty, Chomsky — today publish in the Belgrade Circle Journal, whose special issue on human rights will be published as a book this month by Verso.

Ultimately, it is story of the Belgrade Circle’s founder, the Praxis philosopher Miladin Zivotic, that sheds the starkest light on the Yugoslav tragedy. The foreign intellectuals who were drawn to the Praxis vision of self-managing socialism back in its halcyon days did not take great notice of young Zivotic, whose attentions were devoted mostly to culture. By the 1980s, Zivotic and his students formed a vanguard of poststructuralist scholarship in Belgrade, turning away from the Praxis fascination with Marxism in favor of Foucault and Derrida. Together with the aging dissident Milovan Djilas, Tito’s onetime heir apparent, they founded the Belgrade Circle in 1992. According to Richard Bernstein, “There came a point when Marxism, even Marxist humanism, was old hat. It no longer spoke to the right issues. The Belgrade Circle allowed the younger generation to rebel against the stale clichés of the older generation.”

But Zivotic and his followers made their real reputation as peace activists. During the war years, the Belgrade Circle expanded to include a motley array of workers, filmmakers, intellectuals, and artists. At its height it had five hundred followers, who convened every Saturday for public events geared toward interethnic dialogue and peace.

In 1993, Zivotic traveled to besieged Sarajevo, slipping through Bosnian Serb lines to meet with the city’s Muslim leadership. Back in Belgrade, he received a series of anonymous telephone calls from strangers who threatened to slit his throat. He spoke out in solidarity with Kosovo’s Albanians, and when Muslims in Serbia’s Sandjak region came under threat, he went to live with them in protest. Against ethnic cleansing he proclaimed, “If living together is impossible, then life itself is impossible as well.”

Although he had been permitted to return to the University of Belgrade in 1987, Zivotic was no longer happy there by 1994. He told the New York Times, “I could not stand to go to work. I had to listen to professors and students voice support and solidarity for these Bosnian fascists, Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic, in the so-called Republic of Srpska. It is now worse than it was under Communism. The intellectual corruption is more pervasive and profound.” A friend remembers that Zivotic “was physically destroyed by the time and the evil amid which he lived.”

In 1997, Zivotic gave a talk in London about the anti-Milosevic demonstrations that were then taking place at the University of Belgrade. He knew that the West had high hopes for the activists, but he also knew that their leaders were themselves nationalists. Branka Magas was at this talk. “He was very disappointed with the Praxis people,” she says. “He was a humanist.”

Two weeks later, Zivotic was dead. “He was extremely tormented by what had happened,” says Magas. “He died of a broken heart, I think.”