Why the Left Should Embrace Brexit

Remainers claim that Brexit will be an economic apocalypse. But it provides the opportunity for a radical break with neoliberalism.

Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn delivers speech on Brexit in 2017. (Credit: Getty)

Nothing better reflects the muddled thinking of the mainstream European left than its stance on Brexit. Each week seems to produce a new chapter for the Brexit scare story: withdrawing from the EU will be an economic disaster for the UK; tens of thousands of jobs will be lost; human rights will be eviscerated; the principles of fair trials, free speech, and decent labor standards will all be compromised. In short, Brexit will transform Britain into a dystopia, a failed state — or worse, an international pariah — cut off from the civilized world. Against this backdrop it’s easy to see why Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn is often criticized for his unwillingness to adopt a pro-Remain agenda.

The Left’s anti-Brexit hysteria, however, is based on a mixture of bad economics, flawed understanding of the European Union, and lack of political imagination. Not only is there no reason to believe that Brexit would be an economic apocalypse; more importantly, abandoning the EU provides the British left — and the European left more generally — with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to show that a radical break with neoliberalism, and with the institutions that support it, is possible.

Modelling Dystopia

To understand why the anti-Brexit stance of most European progressives is unfounded and actually harmful, we should start by looking at the most pervasive Brexit-related myth of all: the idea that it will lead to an economic apocalypse. For many critics this is an open-and-shut case, proven simply by citing a much-publicized leaked report prepared by the British government’s own Department for Exiting the European Union (DExEU). The document concludes that all possible forms of Brexit, from remaining in the Single Market to a free-trade deal or no deal at all, would have a substantially negative impact on the UK’s GDP. Estimates range from a 2 percent lower GDP and 700,000 fewer jobs over the next fifteen years to an 8 percent lower GDP and as much as 2.8 million fewer jobs.

This line of argument can be found in a recent article by anti-Brexit commentator Will Denayer, which cites the fact that the report was produced by Britain’s “pro-Brexit government” as proof of its reliability. However, he fails to acknowledge that these forecasts suffer from a neoliberal bias embedded within the forecasting models themselves. The mathematical models used by the British government are highly complex and abstract, and their results are sensitive to the numerical calibration of the relationships in the models and the assumptions made about, for example, the effects of technology. The models are notoriously unreliable and easily manipulated to achieve whatever outcome one desires. The British government has refused to release the technical aspects of their modeling, which suggests they do not want independent analysts examining their “black box” assumptions.

The neoliberal biases built into these models include the assertion that markets are self-regulating and capable of delivering optimal outcomes so long as they are unhindered by government intervention; that “free trade” is unambiguously positive; that governments are financially constrained; that supply-side factors are much more important than demand-side ones; and that individuals base their decision on “rational expectations” about economic variables, among others. Many of the key assumptions used to construct these exercises bear no relation to reality. Simply put, the forecasting models — much like mainstream macroeconomics in general — are built on a sequence of interrelated myths. Paul Romer, who earned his PhD in economics in the 1980s at the University of Chicago, the temple of neoliberal economics, recently provided a scathing attack of his own profession in a paper titled “The Trouble With Macroeconomics.” Romer describes the standard modelling approaches used by mainstream economists — which he calls “post-real” — as the end point of a three-decade intellectual regression.

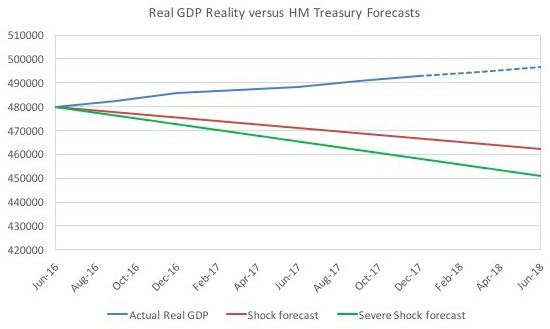

It is no surprise, then, that these models utterly failed to predict the financial crisis and Great Recession, and continuously fail today to produce reliable forecasts about anything. Brexit is an obvious example. In the months leading up to the referendum, the world was flooded with warnings — from the IMF, the OECD, and other bastions of contemporary economics — claiming that a Leave vote in the referendum would have immediate apocalyptic consequences for the UK, causing a financial meltdown and plunging the country into a deep recession. The most embarrassing forecast on “the immediate economic impact of a vote to leave the EU on the UK” was published by the Tory government. The aim of the “study” in question, released in May 2016 by the UK Treasury, was to quantify “the impact … over the immediate period of two years following a vote to leave.”

Within two years of a Leave vote, the Treasury predicted that GDP would be between 3.6 and 6 percent lower and the number of people unemployed would rise by as much as 820,000. The predictions in the May 2016 “study” sounded dire, and were clearly aimed at having the maximum impact on the vote, which would be held a month later. Just weeks before the referendum, the then-chancellor George Osborne cited the report to warn that “a vote to leave would represent an immediate and profound shock to our economy” and that “the shock would push our economy into recession and lead to an increase in unemployment of around 500,000.”

Nonetheless, the majority of voters opted for Brexit. In doing so, they proved economists wrong once again, since none of the catastrophic scenarios predicted in the run-up to the referendum have occurred. As Larry Elliott, Guardian economics editor, wrote: “Brexit Armageddon was a terrifying vision — but it simply hasn’t happened.” With almost two years having passed since the referendum, the economic data coming out of the UK makes a mockery of those doom-laden warnings — and of the aforementioned government report in particular. Data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), shows that by the end of 2017, British GDP was already higher by 3.2 percent relative to its level at the time of the Brexit vote — a far cry from the deep recession we were told to expect.

Meanwhile, the unemployment rate dropped from 4.9 percent to 4.3 percent between June 2016 and January 2018, while the number of people unemployed fell by 187,000 — a forty-three-year low. Economically inactive people — those who are neither working nor looking for a job — fell by the largest amount in almost five-and-a-half years. So much for the countless workers that were supposed to be made unemployed as a result of the Leave vote.

Particularly embarrassing for the professional doomsayers is the data on British industry over the past two years. Despite the uncertainty concerning the negotiations with the EU “manufacturing is seeing its strongest growth since the late 1990s,” according to the Economist as well as the British manufacturers’ association EEF. This is largely due to a growing demand for British exports, which are reaping the benefits of the lower pound and improved world trade conditions. According to a report by Heathrow Airport and the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR), UK exports are at their strongest position since 2000. As the Economist recently put it: “Britain’s long-suffering makers are enjoying a once-in-a-generation boom,” as the shifts induced by Brexit engender a much-needed “rebalancing” from boom-and-bust financial services towards manufacturing. This is also spurring a growth in investment. Total investment spending in the UK — which includes both public and private investment — was the highest of any G7 country during 2017: 4 percent compared to the previous year.

Predictions that a Leave victory would cause the British economy to be crushed by a “run on the pound” have proven equally unfounded: yes, sterling has indeed lost ground to other major currencies since the referendum, but not only has this not destroyed the British economy — quite the opposite, in fact, as we have seen — but its value has been on the rise again since early 2017.

The Sainted Single Market

So, given the paucity of evidence for Brexit precipitating an economic collapse, what was behind the blind certainty of the commentariat? One important piece of ideology undergirding the whole Brexit debate is the notion that Britain enjoyed huge economic benefits from joining the EU (or EEC as it was known in 1973). Does that claim hold up to evidence? As a recent study by the Centre for Business Research (CBR) at Cambridge University shows (see graph below), “there was no improvement in UK growth in per capita after 1973 when compared with previous decades. Indeed, GDP per head clearly grew more slowly after accession than it had in pre accession decade.”

The researchers conclude that “there is no evidence that joining the EU improved the rate of economic growth in the UK.” The much-vaunted establishment of the Single Market in 1992 didn’t change things — neither for the UK nor for the EU as a whole. Even when we limit ourselves to evaluating the success of the Single Market on the basis of mainstream economic parameters — productivity and GDP per capita — there is very little to suggest that it has lived up to its proponents’ promises or to official forecasts. The following graph provides a long-term comparison between the EU 15 and the US in terms of GDP per hour worked (one measure of labor productivity) and GDP per capita.

The data clearly shows that not only has the Single Market (starting at the green line) failed to improve the EU15 economies relative to the US, but would actually appear to have worsened it.

Even more interestingly, the creation of the Single Market has not even boosted trade within the EU. The following graph shows the percentage of exports between EU and EMU [European Monetary Union, developing into the eurozone] countries as a percentage of total EU and EMU exports. After experiencing a steady rise throughout the 1980s, this proportion effectively stagnated between the Single Market’s creation in the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, and has been on a downward trend ever since (with a slight recovery post-2014). A Bruegel note adds that “the Euro Area has been following nearly the exact same pattern as the European Union as a whole, suggesting the common currency might not have had the expected effect on trade between Euro Area members.”

The same applies to the share of UK exports to the EU and EMU, which has stagnated since the creation of the Single Market and has been in decline since the early 2000s (returning to the level of the mid-1970s), with non-EU export markets growing much faster than those within the EU and the eurozone.

As the Cambridge researchers note, this suggests “a negligible advantage to the UK of being a member of the EU.” Moreover, it shows that Britain has been diversifying its exports for quite some time and is much less reliant on the EU today than it was twenty or thirty years ago. A further observation drawn from the IMF Directions of Trade database is that while global exports have grown fivefold since 1991 and advanced economies exports have grown by 3.91 times, EU and EMU exports have only grown by 3.7 and 3.4 times respectively.

These results are consistent with other studies that show that tariff liberalization in itself does not promote growth or even trade. In fact, the opposite is often true: as Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang has shown, all of today’s rich countries developed their economies through protectionist measures. This casts serious doubts over the widespread claim that leaving the Single Market would necessarily mean “lower productivity and lower living standards.” It also exposes as utterly “implausible,” in the words of the Cambridge researchers, the Treasury’s claim that Britain has experienced a 76 percent increase in trade due to EU membership, which could be reversed upon leaving the EU. The Cambridge economists conclude that average tariffs are already so low for non-EU nations seeking to trade within the EU that even in the case of a “hard Brexit” trade losses are likely to be limited and temporary.

The Left and Liberalization

This makes even more ridiculous the contemporary left’s support for “free trade.” We should wince at the thought of what future historians will think of such aberrations as the Labour Campaign for the Single Market, or its allies Yanis Varoufakis and his DiEM25 group. Especially if we consider that even mainstream economists such as Dani Rodrik are now explicitly saying that trade liberalization “is causing more problems than it solves,” is one of the root causes of the anti-establishment backlash engulfing the West, and that the time has come to “plac[e] some sand in the wheels of globalization.” In this sense, one would expect the Left to see Brexit as the perfect opportunity to “rewrite [the] multilateral rules,” as Rodrik counsels — not to cling tooth and nail to a failing system.

Furthermore, it is often forgotten in the debate over Brexit that the Single Market is about much more than just trade liberalization. A crucial tenet of the Single Market was the deregulation of financial markets and the abolition of capital controls, not only among EU members but also between EU members and other countries. As we argue in our recent book, Reclaiming the State, this reflected the new consensus that set in, even among the Left, throughout the 1970s and 1980. This consensus held that economic and financial internationalization — what today we call “globalization” — had rendered the state increasingly powerless vis-à-vis “the forces of the market.” In this reading, countries therefore had little choice but to abandon national economic strategies and all the traditional instruments of intervention in the economy, and hope, at best, for transnational or supranational forms of economic governance.

This resulted in a gradual depoliticization of economic policy, which has been an essential element of the neoliberal project, aimed at insulating macroeconomic policies from popular contestation and removing any obstacles put in the way of capital flows. The Single Market played a crucial role in the neoliberalization of Europe, paving the way for the Maastricht Treaty, which embedded neoliberalism into the very fabric of the European Union. In doing so it established a de facto supranational constitutional order which no individual government has the power to change. In this sense, it is impossible to separate the Single Market from all the other negative aspects of the European Union. The EU is structurally neoliberal, undemocratic, and neocolonial in nature. It is politically dominated by its largest member and the policies it has driven have had disastrous social and economic effects.

So why does the mainstream left have such a hard time coming to terms with Brexit? The reasons, as we have noted, are numerous and often overlapping: the Left’s fallacious belief that “openness” and trade bring prosperity; its internalization of mainstream economic myths, particularly concerning public deficits and debts; its failure to understand the true nature of the Single Market and of the European Union in general; the illusion that the EU can be “democratized” and reformed in a progressive direction; the flawed notion that national sovereignty has become irrelevant in today’s increasingly complex and interdependent international economy, and that the only hope of achieving any meaningful change is for countries to “pool” their sovereignty together and transfer it to supranational institutions.

One important reason for the Left’s embrace of anti-Brexit panic has been the welcome distraction this offers from dealing with a more substantial problem: that the economic system underpinning the West in general is in serious decline. Another study by the aforementioned CBR at Cambridge University found that the impact of Brexit is likely to be much more mild than government forecasts “even if the UK ends up with no free trade agreement or other privileged access to the EU single market” — that is, even in the event of a so-called “hard Brexit.” Overall, the Cambridge researchers found:

The economic outlook is grey rather than black, but this would, in our view, have been the case with or without Brexit. The deeper reality is the continuation of slow growth in output and productivity that have marked the UK and other western economies since the banking crisis. Slow growth of bank credit in a context of already high debt levels, and exacerbated by public-sector austerity prevent aggregate demand growing at much more than a snail’s pace.

In other words, to the extent that the UK continues to face serious economic problems — suppressed domestic demand, ballooning private debt, decaying infrastructure, and deindustrialization — these have nothing to do with Brexit, but are instead the result of the neoliberal economic policies pursued by successive British governments in recent decades, including the current Conservative government.

These deeply embedded neoliberal ideas can only be challenged by a democratic revolution in British politics — but here again the Brexit debate has hampered progress, revealing a profound mistrust of democracy. This is exemplified by the claims that without the “protection” of the Single Market the UK would slip into a dystopian nightmare, where it would be overrun with “genetically modified foods, chlorinated chicken, and access to procurement of protected sectors like health care” and where, as Denayer writes, human rights would be “substantially” reduced, and “principles of fair trials, free speech and decent labour standards” would be compromised. While it may be true that in some areas previous right-wing British governments have been positively constrained by the EU in their push for all-out deregulation and marketization, the notion that the British people are incapable of defending their rights in the absence of some form of “external constraint” is patronizing and reactionary.

Just as Britain’s current economic woes have much more to do with domestic economic policies than with the outcome of the referendum, the country’s future largely depends on the domestic policies followed by future British governments, and not on the result of the UK’s negotiations with the EU. As John Weeks, professor emeritus at the University of London, writes: “The painful truth is that the vast majority of British households will be better off out of the European Union with a Labour government led by Jeremy Corbyn than in the European Union under the yoke of a Conservative government led by anyone.”

Indeed: a democratic socialist government led by Corbyn is the best option for the majority of British citizens and for the British economy. This leads to an obvious conclusion: that for a Corbyn-led Labour government, not being a member of the European Union “solves more problems than it creates,” as Weeks notes. He is referring to the fact that many aspects of Corbyn’s manifesto — such as the renationalization of mail, rail, and energy firms and developmental support to specific companies — or other policies that a future Labour government may decide to implement, such as the adoption of capital controls, would be hard to implement under EU law and would almost certainly be challenged by the European Commission and European Court of Justice. After all, the EU was created with the precise intention of permanently outlawing such “radical” policies.

That is why Corbyn must resist the pressure from all quarters — first and foremost within his own party — to back a “soft Brexit.” He must instead find a way of weaving a radically progressive and emancipatory Brexit narrative. A once-in-a-lifetime window of opportunity has opened for the British left — and the European left more in general — to show that a radical break with neoliberalism, and with the institutions that support it, is possible. But it won’t stay open forever.