Muddling Through Isn’t Enough

Modern democracy seems resistant to programs of sweeping change. But they may be the key to its survival.

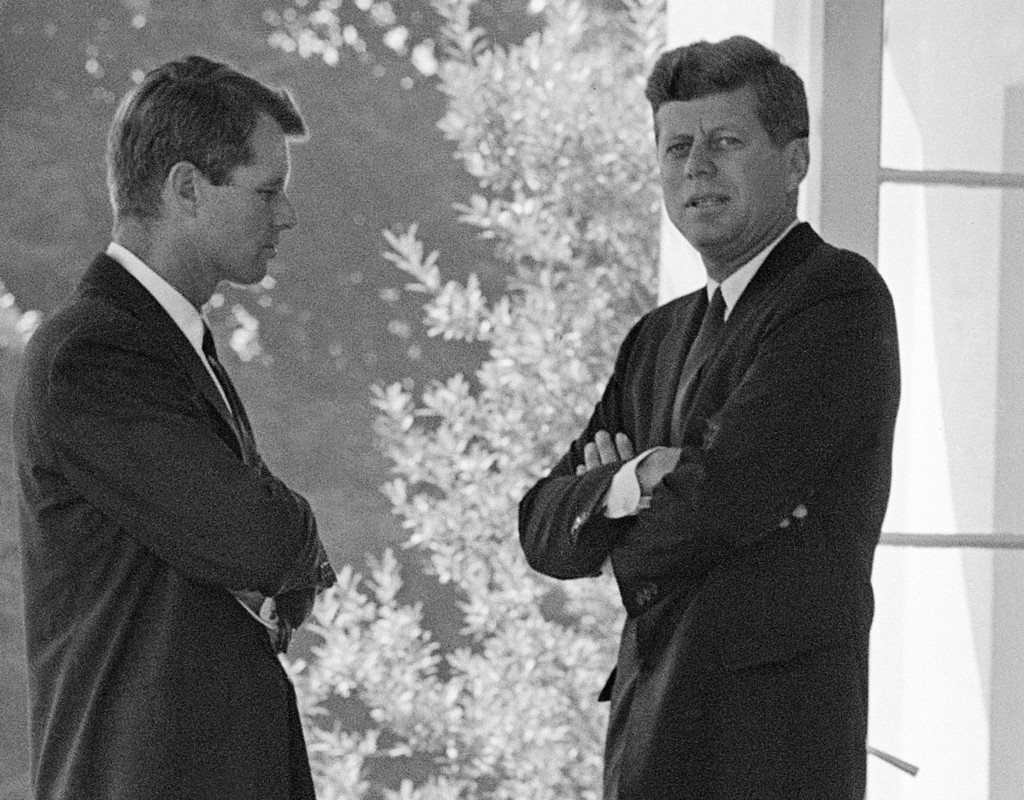

President Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, confer on October, 3, 1962 during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Cecil Stoughton / John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

At the height of the eurozone crisis, in 2011 and 2012, and then again in 2015 when Greece threatened to tumble out of the currency union, one could hear daily laments in the international press about the EU’s tendency to “muddle through” and its preference for “kicking the can down the road.”

The inability to deal decisively with the eurozone’s problems was attributed to the obstacles of democratic politics: too many national leaders constrained by too many domestic publics, each with different wishes, each able to vote prime ministers and presidents in and out of office come election time.

Some grumbled about the EU’s high-handed, technocratic style, but many more complained at its inability to deal swiftly with the banking and sovereign debt crises. The German sociologist Claus Offe captured the public mood in his 2015 book, Europe Entrapped. Unable to move forward, and unable to move back, Europe was the victim of a dramatic absence of political will.

In The Confidence Trap, originally published in 2013 and recently reissued in a revised edition, David Runciman performs the spectacular feat of turning this conventional wisdom on its head. Muddling through and kicking the can down the road are not the regrettable features of a Byzantine European Union whose many parts fail to add up to any coherent whole. Rather, these responses are the hallmarks of how democratic polities deal with crisis. More than that, they’re not failings. They are at the core of what enables democracies to survive and outlive autocratic regimes.

Succeeding by Accident

Runciman’s book isn’t just a defense of elections or the intricacies of slow and cumbersome policy-making. In fact, it is not that at all. It’s about the virtue of “democratic progress through adaptability,” that is, how democracies adapt to crises by default rather than by design, and in ways that are often derided at the time but prove remarkably enduring with hindsight.

Referring to the failure of the 1933 World Economic Conference, Runciman writes that:

The strength of democracy is its ability to turn make-or-break occasions into routine moments of political uncertainty… Democracy is more durable than other systems of government not because it succeeds when it has to, but because it can afford to fail when it has to. It is better at failure than its rivals.

The book’s main claim is that democracies suffer from a “confidence trap.” This is a version of the economists’ “moral hazard” problem, a regular concern for the insurance industry. Moral hazard occurs when responsibility for risky behavior is no longer with the risk-taker: buying life insurance may make someone feel more sanguine about going skydiving or canoeing through white-water rapids. Bailing out the banks may have seemed necessary to save the international financial system in 2008 but it also sent a message to the financial sector: any gains from risky behavior are yours but the losses will be socialized through public intervention.

For Runciman, democracies face their own moral-hazard dilemma. Their ability to survive a crisis by muddling through and adapting at the margin stokes the belief that democracies will always survive crises. This creates the kind of hubris that brings on the next crisis — hence, the confidence trap. When democracies learn that their mistakes are “reparable,” they also begin to think these mistakes may not matter very much. But there is no final reckoning for all these mistakes. The band-aids deployed by democracies are surprisingly durable. What the French call “le grand soir” amounts to little more than the myth of a “day of judgement” borrowed from Christian eschatology. Democracies stumble from one crisis to another, but without ever falling flat on their face.

The various episodes discussed at length in the book suggest that crises are resolved through a mixture of adaptability and experimentation, with a bit of luck thrown in. For example, in 1962, when the German political class was rocked by the scandal of the decision by Franz Josef Strauss, the defense minister, to arrest the editors of a leading magazine, it seemed as if the residual authoritarianism of postwar West German politics, combined with its stolid avoidance of political controversy, had finally met its match. Time for renewal, for change, for a breath of fresh air. But Runciman argues that the so-called “Spiegel affair” was an important turning point only in retrospect. At the time, trivia and gossip dominated public discussion and many of those involved — including Strauss himself — were only temporarily removed from the German political scene. This was political renewal in the absence of any real social or political transformation — but renewal nonetheless.

Runciman’s reading of these past crises is a challenge to anyone who thinks themselves well versed in twentieth-century political history. His book takes on democracy’s many doomsayers — from H.G. Wells to Samuel Huntington — and tries to prove them wrong. Indeed, he suggests that such pessimism constitutes not so much an objective assessment of the capacities of democratic polities to respond to crisis as a part of the democratic condition itself, along with optimism and hubris.

An anti-essentialist message runs throughout the book. For the author, there is no underlying truth to democracy, no core revealed by the pressure of crisis. Instead, two contradictory impulses shape democratic politics — one towards fatalism, the other towards immediacy and hubris. The very desire to find an “essence” or “core” to democracy stokes the hubris that can do democracy so much damage.

Runciman makes this point by comparing two US presidents, Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Roosevelt made a virtue of acting incrementally and experimentally. Wilson, a cautious politician most of his life, attempted towards the end of his political career to “pin democracy down” with his Fourteen Points peace plan. For Runciman, he committed the fatal mistake of trying “to capture the democratic future in the present” — an act doomed to failure given that democratic systems are only interested in short-term considerations.

Crisis in the Long Run

Anti-essentialist claims often contain their own essentialism. In Runciman’s case, we seem to observe the cunning of a certain kind of democratic reason at work. Take political scandals, for instance. Runciman accepts that, more often than not, they focus on voyeuristic trivia. But there’s a method to this madness: such democratic “distractions” help reduce the possibility that crises will usher in radical plans for system-wide change. Levity prevents us from looking too hard at how our democracies work, which saves them from our dangerous tinkering.

He also suggests that the superficiality of democracies makes them more effective at dealing with the most serious crises. The prime example here is the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Though the crisis was profound, with world-historic implications, one of JFK’s principal preoccupations was how his management of it would play out in the forthcoming midterm elections. Far from being a distraction, Runciman suggests these elections prevented Kennedy from being overwhelmed by events.

There is a note of “all’s well that ends well” here. Yet Runciman is far less sanguine about the present “crisis of democracy.” In his 2017 afterword, he takes on Brexit, Trump, and other recent events and asks what they suggest about his original argument. In some respects, they fit well, he concludes, but in general he suggests this time will be different. The reasons he gives for the difference are compelling enough.

One is that on a strictly Tocquevillian reading of democracy — and Tocqueville is Runciman’s main intellectual guide for this journey — the twin tendencies of fatalism and anger aren’t supposed to work their way to the very top of the political pyramid. Citizens, not leaders, are the vessels for these kinds of contradictory impulses. Tocqueville believed that leaders in democracies would resemble schoolmasters, whose relationship to mass publics would be one of stern instruction and enduring patience. But while there was always something schoolmasterly about Barack Obama, Trump has nothing of that.

Runciman also doubts whether the capacity for unlimited experimentation at the margin (as opposed to grand experiments à la Stalin or Mao), which has been the greatest guarantor of democratic survival, still exists in contemporary advanced democratic states. Both fiscally and ideologically, Western societies are exhausted. There is little “slack left in the system.”

But is the boundary between constructive experimentation (FDR) and ad hoc tomfoolery (Trump) as clear as all that? Is it not a matter of political preference whether one considers something to be wise or reckless? And is hindsight not decisive when judging past events? After all, JFK’s concern for the midterm elections during the Cuban Missile Crisis would look rather different had it elicited from him a decision that led to nuclear war.

One problem is that almost all responses to crisis by democratic governments look a little cobbled together when considered from the perspective of a single year — 1947, 1974, 2008, etc. To judge a crisis, we have to widen our perspective, and Runciman recognizes this by ending his chapters with an “aftermath” section. But it is difficult to escape the single-year focus of the chapters. With a broader understanding of crisis, it becomes clear that we see something more than just “renewal without transformation” in democratic political systems.

1974, for instance, was a single moment in a larger historical event — namely, the unwinding of the post-1945 accommodation between capitalism and mass democracy. In 1974, advanced industrial societies like the US and the UK were still trying to salvage something from that postwar social contract. It was not until well into the 1980s that business decisively won its struggle against organized labor. Social change in democracies rarely takes the form of a crisis of the old order, rapidly resolved in favor of something new. But that doesn’t mean no change takes place at all.

Blueprints for the Future

What sort of politics emerges from such an alternative history of democratic development?

The message that perhaps comes out most clearly is that in a democracy, it is very dangerous to dream. Any attempt to transcend the immediacy of the political moment — the scandal, the next electoral test, the struggles within a cabinet or a political party — and advance a grand vision or plan for society is to attempt to tie democracy down with promises about what life might be like in the future. When Wilson shifted from pragmatist to dreamer, he was doomed. FDR survived by refusing to dream at all. JFK’s inability to rise above the electoral pressures during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis is what saved the day. You cannot, argues Runciman, take democracy out of the present and pin it to any particular vision of the future.

But if we take a longer view of crises, and of change within democracies, we see there is a vital place for dreamers. Very few blueprints for change are implemented immediately. Most fall by the wayside, pushed aside by the constant jostling for position that is party politics. But ideas are picked up later, circumstances change, and new opportunities arise. Perhaps it was even these many different ideas about how to achieve the good life that made “democratic progress through adaptability” possible in the first place.

“Muddling through” only really works when it takes place amidst a real debate about how society should be organized. What looks like pragmatic adaptability on the surface is really the struggle — and resulting compromises — between competing interests and competing visions. When raised to the level of an end in itself, muddling through works less well — and that is the problem we have today. Dreaming in a democracy may be dangerous, but we need such dreams if democracy is to survive.