Who Can Beat Trump?

The numbers don't lie: Bernie Sanders would be a formidable general election candidate.

Earlier this month, Vox quoted me in an article that polled various academics about Bernie Sanders’s chances in a general election. My opinion is that Sanders would be at least as strong a Democratic candidate as Hillary Clinton, and perhaps a stronger one.

A few weeks ago, I took a closer look at the familiar case against Sanders on electability grounds: “He would be another McGovern”; “his lead on the GOP in early polls is meaningless”; “he’s too liberal for American voters”; etc. These arguments against Sanders, I argued, rested on a number of faulty assumptions about history, demographics, polling, and ideology.

Vox reporter Jeff Stein interviewed two of the political scientists whose work I cited. I’m far from an expert on presidential politics — or political science generally — and I admit I was a little concerned that my arguments might be exploded by scholars with a much deeper background on these issues.

But after reading the piece, it seems to me that that neither Stein nor the specialists he interviews address the substance of my arguments, or responds to my data analysis with a competing analysis of their own.

In defense of polls showing Sanders with large leads over GOP rivals, I cited Robert Erikson and Christopher Wlezien’s book The Timeline of Presidential Elections. Over the last half century, they found that “trial heats” between hypothetical Democratic and Republican candidates, as early as April, generally yielded results that weren’t far off from the final outcome in November.

Stein writes that this conclusion “evades the core of Erikson and Wlezien’s findings.” I don’t think that’s a fair characterization. Here’s how UCLA political scientist Lynn Vavreck characterized Erikson and Wlezien’s book in her 2014 review in Perspectives on Politics:

The book makes three important points. The first is simply to illustrate for readers the impressive aggregate-level stability that defines most election-year poll results and how closely those polls are tied to eventual outcomes. Beginning in April of each year and going through to November, Erikson and Wlezien show that in each of the 15 years they investigate, the early polls (even several hundred days out) do a pretty good job of characterizing the eventual outcome.

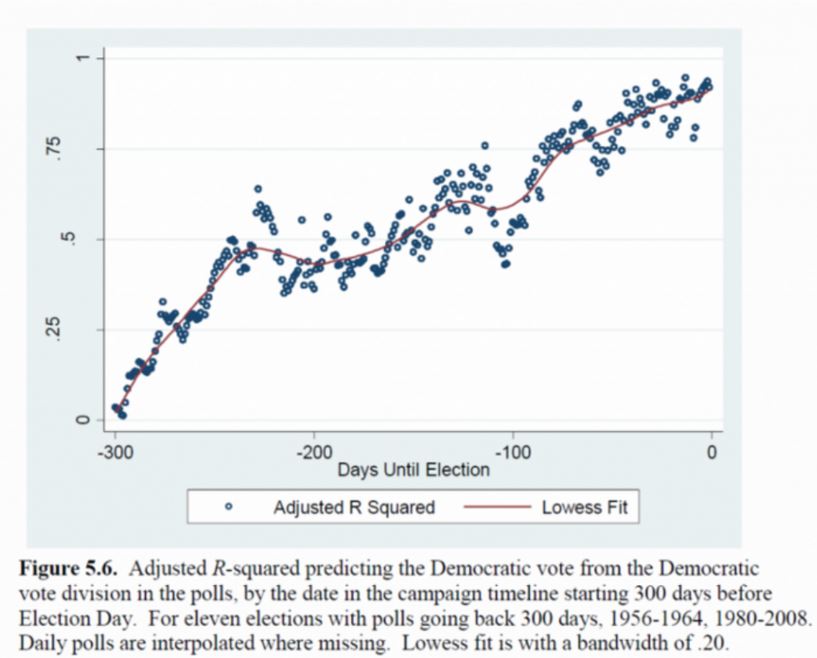

Stein cites an “online summary” of the book, which downplays the significance of polls taken “early in the year.” But I don’t think any online summary of Erikson and Wlezien’s volume holds as much weight as the data in the book itself. Here’s one chart from the book that shows how closely trial heats from around 270 days before the election have tracked with final results in November.

The same stable pattern held for the 1996 and 2012 elections, too. Erikson and Wlezien’s overall results — and commentary about the meaninglessness of early polls — are heavily dependent on results from elections between 1952 and 1992.

As I wrote in my earlier post, I think there’s a good case to be made that increased polarization over the last twenty years has resulted in a much more stable electorate. Of course this is just a hypothesis, presented by a non-specialist — but neither Erikson nor any of the other specialists in the Vox piece even address the idea, let alone take time to explain why it might be wrong.

It’s worth adding that it’s now March 14, and Election Day in November is now just 238 days away. If anything, the trial heat polls showing Sanders in the lead over GOP favorites Trump or Cruz — which remain as consistent as ever — have grown more meaningful.

Even leaving out the relatively stable 2012 election, Wlezien’s own r-squared chart indicates that trial heat polls from about 240 days out, while far from infallible, are significantly predictive. My guess is that a chart that only included data since 1992, or even since 1980, would show even greater significance.

Stein also interviewed D. Sunshine Hillygus, whose work I cited as evidence that so-called “moderate” voters actually tend to hold a number of strong competing views — and hence might be drawn to Sanders’s strongly liberal economic program. Hillygus seems to disagree that Sanders might appeal to these “cross-pressured” voters, and of course she’s entitled to her opinion.

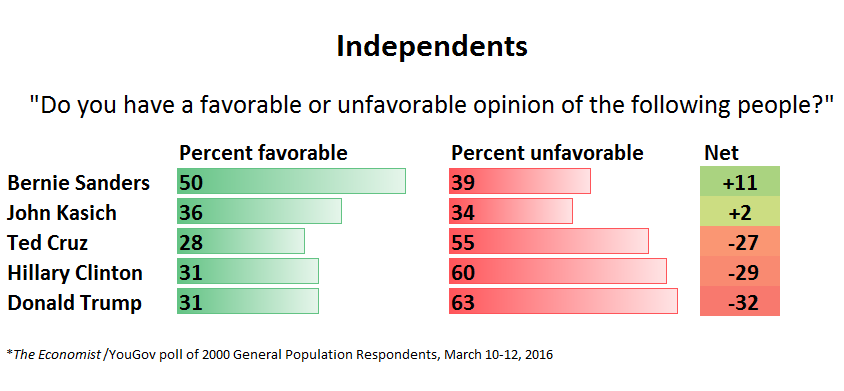

But there’s nothing in her reply — or Stein’s piece as a whole — that deals with the well-established pattern of independent voters overwhelmingly preferring Sanders to Clinton, both in primary elections and in trial heats versus Republicans. Nor does it address the occasional phenomenon, seen in New Hampshire and Oklahoma, of “moderate” and “conservative” Democratic primary voters breaking for Sanders.

I think these results are consistent with Hillygus’s portrait of “cross-pressured” voters responding to Sanders’s economic message, even if they are quite conservative in other ways. In a campaign against Donald Trump, Sanders has a powerful means to appeal to these independents. Hillary Clinton, despite her more “moderate” positions on a number of issues, has virtually none.