The Socialist Who Helped Bring Marx to America

The early-20th-century socialist and New York mayoral candidate Morris Hillquit saw liberalism and democracy as providing a foundation for a transition to socialism. Alongside Eugene Debs, he helped to forge a distinct American socialist tradition.

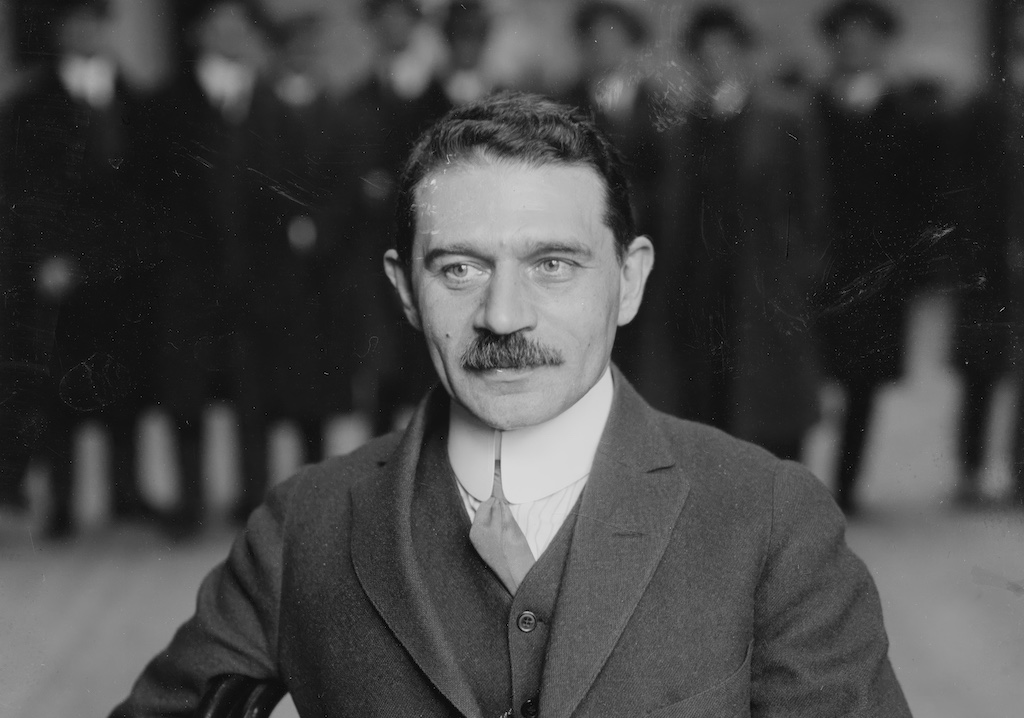

Portrait of Morris Hillquit taken between 1910 and 1915. (Heritage Art / Heritage Images via Getty Images)

In the summer of 1920, Benjamin Schlesinger, president of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), sailed for Europe and Soviet Russia. The ILGWU — then one of the six largest unions in the United States and among the most left-wing within the American Federation of Labor (AFL) — sent him officially to attend the International Clothing Workers’ Congress in Copenhagen. But what Schlesinger remembered most of his trip was an impromptu midnight meeting in Moscow with Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the world’s first socialist state.

The encounter, held in Lenin’s modest Kremlin office, was informal and warm. As Schlesinger later recalled, Lenin greeted him not as a foreign dignitary but as a comrade. “Before I realized it, I knew that we kissed each other, Russian style, and it appeared so simple, so matter-of-course-like to me.” He went on to describe a man whose

eyes are kind and laughing, especially when he is engaged in conversation. Lenin laughs very frequently, giving a start every time something strikes him particularly funny. . . . After two minutes talking with him, I thought I knew Lenin for a number of years; not only knew him, but that we were friends and comrades for a long time. There was not a trace of ceremony or officiality about the entire affair. We kept on constantly interrupting each other and breaking into one another’s talk. And then his reassuring smile and laughter! There was something genuinely bewitching about it.

There was, however, a moment of slight tension when the subject of some openly anti-Bolshevik Socialists came up:

In the course of our further conversation I mentioned the names of Spargo and Walling. Lenin almost trembled with indignation. “These are vermin,” said, “recently someone showed me their books about Russia. I could not see further than the first two pages. It nauseated me; they are traitors of the worst kind.”

“The Socialists in America will probably have no quarrel with you regarding your definition of these men,” I said, “but I am under the impression that you have called Kautsky ‘traitor’ too. I know Kautsky, and I wish to confess that every time I read you calling Kautsky ‘traitor’ it grievously pained me.”

“We never impute dishonesty to Kautsky. He is doubtless very honest in his opinions,” Lenin said, “but we do say that he went off the right course, and that his attitude towards Russia is unforgivable.”

Yet, surprisingly, Lenin then expressed respect for another Socialist leader, Morris Hillquit, whom he characterized as “an honest Socialist, bound by principle though limited by circumstance.” Hillquit was the American Socialist closest to Schlesinger: as the lawyer for the ILGWU, he was a close collaborator with Schlesinger in union affairs. Both were pillars of New York’s Jewish socialist/labor world — a world whose dominant institutions included the Jewish Daily Forward, the United Hebrew Trades (a federation of Jewish labor unions in New York City), and the Socialist Party of America (SPA) — and the two men operated in the same orbit.

What makes Lenin’s words of praise curious is that Hillquit’s views were closely aligned with those of the man Lenin had dubbed the “renegade Kautsky.” And Lenin’s approbation was all the more curious given that condition seven of the official “Conditions of Admission to the Communist International,” published just a month earlier under Lenin’s guiding hand, had included Hillquit by name among a group of “notorious opportunists” who must be repudiated by any national party desiring membership in the Comintern.

From Riga to the Lower East Side

Born Moishe Hilkowitz in Riga in 1869, the “notorious opportunist” Morris Hillquit grew up under the restrictions and pogroms of the Russian Empire. He belonged to a generation of Jewish intellectual workers radicalized by tsarist repression and drawn to the promise of socialism. Like tens of thousands of others, he joined the migration to New York’s Lower East Side, arriving in 1886.

There he worked as a garment cutter by day and studied law at night, eventually becoming a defender of fellow workers before the courts. And it was as a new immigrant, gathering with other youngsters, after a long day of working in the grueling conditions of the garment industry, on the roofs of Cherry Street on New York’s Lower East Side, singing, laughing, but most of all vociferously arguing the relative merits of anarchism, positivism and socialism — Peter Kropotkin, Auguste Comte, and Karl Marx — that he found himself drawn to and convinced by the logic of Marxism.

The two worlds he had known — tsarist autocracy and American democracy — shaped his politics. From the first, he learned the futility of underground conspiracy; from the second, the potential of legal agitation, organization, and free speech. Hillquit’s conviction that socialism could advance through ballots rather than barricades came directly from the contrast between these experiences.

From De Leon to Debs

By the 1890s, Hillquit had joined the Socialist Labor Party SLP), led by Daniel De Leon, a Columbia. University–trained scholar turned firebrand. De Leon imagined socialism as a kind of disciplined army: workers organized by industry, drilled in doctrine, and directed by a centralized party. But his sectarian authoritarianism alienated many, including Hillquit, who saw in De Leon’s denunciations of unions and rival parties a dogmatism incompatible with democracy.

Hillquit, along with Meyer London and Henry Slobodin, led the 1899 revolt that broke with De Leon’s SLP and helped found the Social Democratic Party, which soon merged with Eugene V. Debs’s forces to create the SPA in 1901.

Where De Leon saw workers as soldiers awaiting orders from the socialist high command, Hillquit saw citizens who must be persuaded, educated, and organized within democratic institutions. His socialism was Kautskyan: class struggle expressed through elections and unions, not insurrections. Capitalism, he argued, was already socializing production; socialism would simply make that tendency conscious and democratic.

Debs and Hillquit: Prophet and Engineer

If Debs embodied the moral passion of American socialism, Hillquit was its theoretical and strategic brain. Together they made an improbable but effective pair: the railway fireman turned orator and the Jewish lawyer-intellectual from the Lower East Side. Debs spoke in parables of justice and solidarity, Hillquit in the measured cadences of legal argument. One could move a crowd to tears, the other could draft a platform to win an election and write carefully reasoned pamphlets and books, appealing to, and trusting in, the intelligence of his readers.

Their cooperation symbolized the SPA at its height — a fusion of moral idealism and organizational realism. Debs was jailed for opposing World War I; Hillquit defended him before the courts and the public. Both saw socialism not as a dream but as history’s next stage. In Socialism in Theory and Practice (1909) and Socialism Summed Up (1913), Hillquit wrote that socialism was “the natural outcome of social evolution.” Marxism, he insisted, was “a science of society, not a gospel of revolt.”

The American Marxist

Hillquit’s lifelong project was to translate Marxism into the idiom of American democracy. Following Kautsky, he believed that socialism would arise from capitalism’s contradictions, not from a conspiratorial plotting. Yet unlike European Marxists, he held that the United States offered a uniquely favorable terrain for peaceful transition. Its democratic framework — universal suffrage, a free press, and freedom of assembly — gave the working class the tools to conquer political power legally. “The conquest of political authority,” he wrote, “can and must be achieved through the lawful exercise of democracy.”

This wasn’t Bernsteinian revisionism — Hillquit still envisioned temporary compromises as part of the road to the end of private property, the abolition of the market, the socialization of industry, and the end of the wage system; and he never would have said, as Bernstein did, that “the movement is everything, the end is nothing.” Yet he rejected violent revolution as both impractical and unnecessary in a country where workers already had the vote. His vision was of industrial democracy — the extension of political rights into the economic sphere.

That perspective made Hillquit the intellectual architect of what later historians would call “American Marxism.” He regarded the Constitution not as a bourgeois trap but as a usable instrument, a set of forms to be filled with new social content. The socialist task, as he saw it, was to complete the democratic revolution the American Republic had only begun.

Opponents to the Left and Right

Within the socialist movement, Hillquit’s moderation earned him enemies on both flanks. When the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) emerged under the charismatic “Big Bill” Haywood, preaching sabotage and the general strike, Hillquit warned that “insurrection without organization is chaos.” Haywood, a former miner with one eye and a commanding presence, saw Hillquit as a timid intellectual. Their feud at the SPA’s 1912–13 conventions split the party: the IWW wing walked out, accusing Hillquit of bureaucratic conservatism; Hillquit accused them of adventurism that would doom the cause.

For Hillquit, socialism was not a rebellion against law but its extension to the economic sphere — “industrial democracy” realized through collective ownership and political majorities.

The ILGWU, where Hillquit served as counsel and strategist, embodied this tension. It was one of the few AFL unions explicitly committed to socialism; yet it was also deeply pragmatic, balancing militant strikes with collective bargaining and legal contracts. For Hillquit, this synthesis — mass action within a legal framework — was the essence of Marxism adapted to American soil.

Building — and Losing — Coalitions

The SPA that Hillquit helped construct was a fragile but remarkable coalition: immigrant garment workers, Midwestern farmers, trade unionists, and radical intellectuals. Under his organizational discipline, the party grew to nearly 120,000 dues-paying members by 1912 and elected hundreds of local officials, including Congressman Victor Berger of Milwaukee. In that year’s presidential election, Debs won 900,000 votes — the high point of Socialist electoral power in the United States.

But holding such a coalition together proved impossible. The AFL, under Samuel Gompers, rejected political action, insisting that unions should deal only with “wages, hours, and conditions.” The IWW condemned the SPA as bureaucratic and reformist. In the wake of the success of the Russian Revolution, the party’s left wing broke away (actually, was expelled), taking most of the membership with it. And when the United States entered World War I, repression and hysteria shattered what unity remained.

Hillquit and Debs led the party’s antiwar opposition, condemning the conflict as imperialist. The government answered with censorship, arrests, and mob violence. Debs went to prison; the magaine The Masses was banned; and Socialist rallies were attacked. Yet Hillquit’s 1917 New York mayoral campaign, run under the slogan “For Peace and Democracy,” drew 145,000 votes — nearly 22 percent of the total. For a bespectacled immigrant lawyer denouncing the war from the Left, it was an extraordinary showing.

That campaign marked both the zenith and the turning point of Hillquit’s influence: the last moment before the Russian Revolution, the Red Scare, and the Communist split transformed the terrain entirely.

Revolution Abroad, Repression at Home

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 divided the world socialist movement. To many young radicals, Lenin’s success made Hillquit’s parliamentary socialism seem obsolete. The newly formed Communist parties denounced the SPA as cowardly, while the state unleashed the Palmer Raids against radicals of every stripe.

Hillquit’s answer came in his 1921 book, From Marx to Lenin, a systematic defense of democratic Marxism. The Bolshevik version of the dictatorship of the proletariat, he wrote, had become “the dictatorship of a party.” True socialism required universal suffrage, civil liberties, and the rule of law — the very institutions the Bolsheviks had suppressed. His argument anticipated later social democratic critiques of Stalinism: socialism without democracy, he warned, would reproduce despotism in a new form.

But history was moving the other way. The Red Scare decimated the SPA; tens of thousands joined the new Communist movements. Within the ILGWU, factional wars mirrored the international split, as Communist shop-delegate groups fought Socialist leaders for control. Hillquit’s faith that procedure and persuasion could reconcile class conflict looked increasingly naive in an era of repression and unemployment. By the mid-1920s, Hillquit was, in effect, a lawyer for a cause that had lost its client.

Why Hillquitism Failed

Historical conditions doomed the Hillquit vision to failure. His strategy required a mass labor base and a political system open to third parties — neither of which the United States possessed. A constitution that privileged contracts and private property, a court system that protects them at every step, the two-party structure, the ethnic and craft fragmentation of the working class, and the ideological conservatism of the AFL all blunted socialism’s advance.

In Europe, Social Democrats paired electoral politics with powerful industrial unions, building generous (though still vulnerable) welfare states from that alliance. In America, by contrast, the New Deal absorbed the Socialist agenda into liberal reform, preserving capitalism while neutralizing its opposition. As the German Communist Rosa Luxemburg warned, “If we take the stand of social reform as an end in itself, then the socialist movement degenerates into a bourgeois reform movement.” Hillquit, ever the gradualist, believed that expanding democracy was itself revolutionary. Both were partly right: without mass struggle, democracy stagnates; without democratic institutions, socialism perishes.

The Hillquit Dilemma

By the time of his death in 1933, Hillquit had seen his movement battered by red-baiting and sectarianism. Yet he never abandoned the conviction that democracy and socialism were inseparable. “To destroy democracy in the name of socialism,” he wrote, “is to destroy the seed in order to hasten the fruit.”

Today’s American left inherits Hillquit’s dilemma in a new key. The Democratic Socialists of America, the Bernie Sanders campaigns, and the growing progressive bloc in cities like Chicago and New York all operate within capitalist democracy, hoping to transform it from within. Their challenge is the same one Hillquit faced: how to turn electoral reform into structural transformation without being absorbed by the system they seek to change.

Hillquit’s failure needn’t mean the democratic road to socialism is closed — it only shows that democracy alone is not enough. Without effective communication that is sensitive to the needs and beliefs of its audience, mass organization, independent working-class power, and economic leverage, elections become safety valves rather than engines of change. Yet the historical record is equally clear: without democracy, socialism curdles into tyranny.

Hillquit believed that socialism in America must speak the language of American democracy — not as camouflage, but as fulfillment. The republic’s best ideals — equality, popular sovereignty, the rule of law — could reach completion only through social ownership. As a Marxist, he understood that this goal required the maturation of economic and political conditions beyond his time.

The road he charted remains unfinished. But his central intuition endures: that the fight for socialism in America will pass, as it always has, through democracy itself — crooked, uphill, and incomplete.