New Deal–Era Leftists Tried to Win Beautiful Social Housing for the Masses

The US housing system is organized around subsidized private homeownership and underfunded public housing. But during the New Deal, leftists had a different vision: beautiful social housing for all but the rich.

Children playing at the Carl Mackley Houses in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1935. (Alfred Kastner papers, Collection No. 7350, Box 45, Record 12, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming)

- Interview by

- Daniel Denvir

Few things so define US society, politics, and economy like housing. It is an asset unlike any other, an unrivaled motor of the real and financial economy around which wealth, power, status, and security orbit. It powers the system at the highest level and commands allegiance to it from below.

The United States has a two-tier housing system, with a dominant private market organized around private homeownership and a much smaller and heavily stigmatized, underfunded, and — in recent decades — increasingly privatized public housing system reserved for only the very poorest.

In her 1996 book, Modern Housing for America: Policy Struggles in the New Deal Era, Gail Radford tells the story of Catherine Bauer, the Labor Housing Conference, and the New Deal–era struggle to make the American housing system a radically social one. In place of the two-tier system that won out, Bauer and her allies proposed a massive federally backed system of noncommercial housing that would appeal to and house the majority of Americans in beautiful homes and vibrant, socially connected communities.

Radford’s book has been rediscovered in recent years by a new generation of housing and tenant organizers. In fact, the stories Radford tells have helped inspire me to do the organizing I’m doing to win a statewide public housing developer — to build mixed-income housing that will house both poor and working-class people and appeal to the majority, and in doing so, drive down rents across the board.

This interview, which originally appeared on Jacobin Radio’s The Dig, has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Homeownership Before the Great Depression

Your book is about the fork in the road, when the dream of a more socially oriented US housing system lost out to the system we have today. But before we get there, where did the attachment to private homeownership as core to being an American come from? What did that look like in the decades leading up to the Great Depression?

I’ve always been skeptical of this idea that homeownership was so important and innate in Americans. Before the 1930s people tend to think of the big industrial cities as places where the poor lived. Maybe they have some hazy idea that the poor were in tenements, but of course they weren’t, except in New York City. Families built small wood-frame houses for themselves when they could. They bought these, but they also constructed them themselves. They had no services, in many cases, no indoor plumbing.

But they did, when people were able to purchase them, provide a kind of security that we never have as renters.

Political elites and economic players have done a lot to promote this conception. There were efforts during the 1920s to showcase houses, to introduce Americans to more appliances and so forth, to get people more oriented toward buying their own house and furnishing it.

And then people in the housing industry are very good at propagandizing the idea that owned homes are wonderful. If this was something they could expect that people would believe in the first place, it seems hard to think that they would bother. So to some extent, I think we’ve been propagandized by this idea.

It also has to do with getting away from landlords. Landlords are terrible in general. You’re living under a kind of arbitrary rule that many people in Europe don’t face. People in Europe oftentimes live their whole lives in apartments, but they have rent control and rights that give people protections and stability.

And so there’s this kind of lust for homeownership. Maybe it comes out of the frontier or the American experiment or just sort of as a side effect of being a settler society. But the proposition that homeownership specifically is this innate, powerful drive — I’m skeptical of that. Land speculation, real estate speculation — that seems a better interpretive framework for me.

Let’s get into the historical narrative. Why, in the first decades of the twentieth century, did the cost of housing begin to skyrocket, and what were the consequences of that on the ground? And then how did the politicians, social workers, and policy makers of the Progressive Era — from the radical Edith Elmer Wood to more mainstream proponents of market solutions — propose fixing the escalating crisis?

Part of the problem was the increasing cost of materials. But another part was savings: there were now other places for people to save their money, besides just putting it into building a house that they might sell or rent to someone else. Real estate was not the only possibility for small savers, and that meant that a lot of the housing, by the time we get to the 1920s, was not developed by small-scale speculators, but rather larger development operations.

Once this happens, these larger developers want a higher return on their investment, and so they build primarily for the top of the market. There was a tremendous amount of residential construction during the 1920s, but most of it was aimed at the top third of the market, and that segment was satisfied by the time we get to the middle of the decade.

This is one of the lead-ups to the Depression. People didn’t notice it at the time. Housing, along with cars, was among the drivers of this very hot economy in the Roaring ’20s. But housing production was starting to get less profitable because the product that was being produced wasn’t affordable.

Even for middle-income people, housing was a very risky proposition, in part because of the way mortgages were organized at the time. You got a mortgage, and it only lasted for five or six years. You made monthly payments, but those monthly payments were only on the interest. And so when the mortgage ended, you owed the bulk of it. When times were good, your lender would just turn over your loan and things would just start again and you’d be paying off interest. But as the ’20s went on and then into the 1930s, lenders were not interested in refinancing mortgages. And a lot of people were foreclosed on.

During World War I, Congress for the first time authorized the federal government to directly construct housing — for industrial workers in this case. How did the war remake the debate over government intervention in the housing market, given how intensely hostile business interests and prevailing ideologies had been to anything infringing upon the private sector and private homeownership in particular? You cite a quote from 1918, from Senator Albert Fall, who called federal housing programs “an insidious, concerted effort to overturn the entire government of the United States.”

The housing was actually extremely appealing. There’s still much of it still in existence today. A lot of it was large neighborhoods that were planned by designers who were familiar with the latest theories of garden cities that had been popularized in Great Britain.

But before I talk about the actual housing that was built and the neighborhoods, let me just answer your question about why. What was the opening for these programs in the first place? The crowding and lack of any facilities around a lot of the war plants were incredible. The manufacturers couldn’t get a workforce because there was no place for workers to live. And so, it was a crisis situation in terms of running an industrial war. That’s what made it possible to set these plans in motion for shipbuilders and also war manufacturing of other kinds, especially. These were places along the East Coast, but there was some building on the West Coast too.

The design people who got hired to run the program were extremely talented, and these communities they created were charming. Unfortunately, it got shut down immediately when the war ended and the government started selling them off piecemeal to the highest bidder. There were efforts by residents to set up some kind of co-op arrangement and buy them as a group from the government. These couldn’t get established fast enough, and the whole thing ended abruptly. But a lot was built before it ended.

So these neighborhoods really did pose something of a competition. Some were rowhouse developments, but some were freestanding and grew closer together. They had parks and community facilities integrated into the neighborhoods. These really were extremely appealing alternatives.

The World of Catherine Bauer

The star of your book is a remarkable woman named Catherine Bauer, who in 1934 published the book Modern Housing, and later went on to lead an organization called the Labor Housing Conference.

To start, who was Bauer? How did she develop her interest in housing? And what did she mean by modern housing? What did she propose in terms of the economics of home-building, the government role in home-building, the design of homes, and how a family’s home would be embedded in larger developments, communities, cities, and really entire metropolitan areas?

Catherine Bauer started out as a person who was very interested in art, architecture, and culture. When she was just out of college, she went to Paris and took in these various streams of modern art and culture. And as time went by, she became involved with Americans and Europeans who were interested in the housing question. Partially by accident, she ended up being part of a study group of architects and urban planners in the United States who were influenced by the European housing movement. They were very much concerned with creating a more egalitarian way of living.

Bauer traveled through Europe and met a number of the leading architects in the 1920s. There were a lot of cities throughout Europe that were funding housing, and so the leading architects of the time — who we associate with international-style modernism — were very excited about these commissions that were available to them, where they could build on a large scale and also use some new materials and techniques to bring costs down.

Bauer was taken with all of this. She wrote about it and spent a lot of time with Americans who were interested in implementing some of these ideas here in the United States. And that’s the basis of her book, Modern Housing. She didn’t mean modern in the sense of more modern architecture, necessarily. She meant up-to-date housing, with the kinds of amenities and possibilities that the new kinds of building could bring. As you say, she is the heroine of my book — that’s where I pick up my title, Modern Housing for America.

Bauer was able to move in a lot of different circles and integrate a lot of ideas, and she was able to kind of package them in a way that made them more legible and understandable to a fairly wide audience. But as time went by, she changed. She was no longer a kind of art dilettante, and she was no longer just focused on design questions the way she had been when she kind of got started.

She started to understand that to put some of these ideas into practice, there had to be a political movement, and one had to attend to the financial dimensions, which she initially was not really concerned with.

And coming into her own politically also marked her moving out of the shadow of and away from her lover, Lewis Mumford.

Mumford was very important in her life. She met him by chance. She was working at a publishing house. He was married, but they had an affair that went on for several years. He found her a wonderful intellectual companion as well as romantic partner. And on her side, she learned an enormous amount from him.

But he felt that, according to her, society was just moving in a progressive direction and that the hopes for a more rational, just society would kind of just emerge.

That there was some sort of innate, embryonic communism that modern society would just sort of produce.

Yes, exactly. And about the same time she was having real questions about this and feeling that he wasn’t really responding to the moment. She also felt that he wasn’t responding to the moment when he had to make a choice between her and his wife. His attitude was that he didn’t need to because it was fine with him if everything just continued as it was. But she became restless and became involved with people who had a more political orientation.

The key person here was an architect named Oscar Stonorov, who had a European background and came to the United States with aspirations to be a kind of Ernst May for the United States. May was a city planner for the city of Frankfurt in the 1920s, and he had just designed a lot of the housing that was built in Frankfurt: terrific, still-standing, wonderful examples of the kind of thing I was talking about earlier, where the architects were able to get big commissions to build in large-scale ways in Europe in the ’20s.

So Stonorov was much more of an activist, as well as an architect, and was connected with the labor movement. Bauer came to believe that the only way that new housing possibilities were going to happen was for organized groups of people who wanted good, affordable housing for themselves to demand this politically.

As you touched on, the rise of social housing in European cities was a key reference point for Bauer and for others in her milieu. Why, after World War I, did so many European countries build out a massive amount of noncommercial housing? What factors, from intense working-class militancy to theoretical currents like utopian modernism, led to that happening? And what did Bauer and her cohort learn from places like Red Vienna?

Let’s start with Red Vienna, which is still an international showcase for social housing. There was a housing crisis in Vienna after World War I. It wasn’t caused by the war — there had been severe housing shortages and unaffordable costs before — but the war made everything worse.

After the war Vienna was the capital of a small state, whereas before it had been the center of this huge empire. There was unrest throughout Europe and even revolution. The bourgeoisie were very frightened about the possibilities of being expropriated, and the strongest party in Vienna was the Social Democratic Workers’ Party.

The Social Democrats who took over the city council were very oriented toward a more egalitarian world, and housing seemed to them a critical good that they needed to try and provide for their constituency. There was a lot of energy from the bottom to have better housing options. But one of the features that made their housing program possible was the fact that the industrial elite believed that the Social Democrats were their best bet of protecting themselves against some kind of revolutionary event.

Because of that, these elite were willing to allow the Social Democrats to institute these very draconian taxes on property. Essentially, the industrial capitalists cut loose the property-owning part of capital. By the end of it — building started in 1923, and continued for a decade — 10 percent of the population was rehoused. It was phenomenal.

The government didn’t contract with for-profit builders, but instead directly financed it. The city government set up firms that would create materials, cement, and lumber for flooring, so the programs that were put in place — which in the United States would be carried out by private operators — were all kept in-house, and therefore the government wasn’t helping the real estate industry become more powerful within politics.

So it was the most aggressive example of the social housing movement in Europe at this time, but there was large-scale building in Germany and other countries as well.

One other key factor that you mentioned — one that you write Bauer failed to account for — was the fact that the real estate industry was a less powerful force in this period in European capitalism than it was in the United States, something that made non–real estate capitalists in Europe much more willing to support noncommodified housing.

Right. And partially because it helped them. That’s a piece that I should talk about, regarding industrial capitalists in Vienna. The important thing for them was keeping wages low. And part of that had to do with keeping housing prices and rents low. So that’s one of the reasons they were willing to put up with what was really a major blow to capital being in charge of things. They were willing, as I said, to cut loose the property owners in order to save themselves. And those groups weren’t as tightly integrated as they have been historically in the United States.

Here in the United States, real estate speculation is just part of everything — it’s not such a distinct feature — and it’s also incredibly powerful. Every congressional district has boards of realtors, has developers who are organized in groups, and at the national level as well, manufacturers who are still involved with real estate. I mean, these days, institutions of higher learning are real estate operators; hospitals are real estate operators. And it’s so connected and so politically powerful. We’ve just finished with our developer president, but George Washington was out there laying out property as well.

Housing and the New Deal

The Great Depression wreaked havoc on the housing industry, bringing construction to a halt and causing foreclosures to skyrocket, which was both a signal of the general crisis and a major sectoral motor of that crisis. The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 created the Housing Division, part of the Public Works Administration (PWA), marking the first non-wartime direct federal intervention ever into the housing market.

What was the Housing Division? Who led it, and what factors made it, as you write, “significantly influenced by those who hoped to initiate a single, broad policy approach aimed at the majority of Americans?”

When the National Industrial Recovery Act was passed, part of the money was put into a public works agency that was headed by a man named Harold Ickes, the head of the Department of the Interior. He started out as a progressive, reform-minded Republican in Chicago, which was very corrupt, very rough and tumble. And Ickes came out of that experience, along with maybe just his innate character.

He had a few rough edges.

Yes. He was quite rigid. I have a soft spot for him. He was an anti-racist, and he was very incorruptible personally. People who worked with him found him difficult, partially because he was so controlling — everything had to come over his desk. But in his defense, he was really set on not having scandals break out that would undermine the political strength of the New Deal. And anything having to do with real estate is always vulnerable to self-dealing and corruption.

The PWA did a lot of big projects — dams, electrifying railroads, and so forth. But Ickes segmented off a piece of it that would be the Housing Division and hired design professionals and public and urban planners who had been influenced by these kinds of ideas that we’ve been talking about — ideas developed in Britain, their garden cities, the international mass-housing movement. These ideas about design were just coursing through this world of architecture and urban planning.

So it was only reasonable that many of these design ideas were tried out by the PWA.

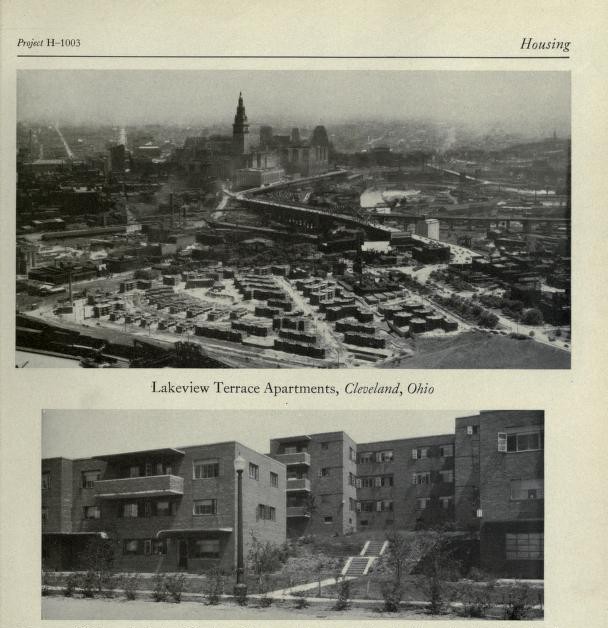

Just to give you a concrete sense of what I’m talking about: one of the very nicest of the PWA projects was built in Cleveland — Cleveland Terrace. I was lucky enough to have a conversation with the lead architect on that project years later. His name was Wallace Teare, just a really lovely person. I asked him if he was aware of these building projects that were going on in Europe. And he said, “Oh, yes.” He said, “Like a lot of architects in that period, I had these designs that I wanted to try out. And I kept them in a drawer because I couldn’t get any because there were no commissions to be had in the 1920s for large-scale projects.”

So Teare was part of a national group of people who were aware of what was going on but had no way of putting any of it into action — until the Housing Division starts making it possible to build projects throughout the country, eventually around fifty. These designers were part of this conversation that Bauer was so seminal in developing.

The 1932 election not only elevated Franklin Roosevelt to the presidency, but also elected a Congress within which, you write, “non-Southern Democrats represented a working majority in the House for the first time of what would be only a few times in the 20th century.” And you write that Roosevelt and the New Deal liberal Democrats envisioned housing policy as a way to give people stable, affordable homes to revive the economy and to make their base into a constituency that would underpin a permanent Democratic majority.

What were the various ways these people envisioned housing policy? What was the state of the debate over what to do about housing within the New Deal coalition?

You ask about the ideas of the people at the center of the New Deal. At the point the Roosevelt administration comes in in the spring of 1933, home foreclosures were running at a thousand a day. And the financial industry that was involved with mortgages was on the verge of collapse. So it wasn’t surprising that one of the very first things the administration did was set up a temporary program called the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), and the HOLC refinanced something like a million home mortgages.

But it didn’t do anything to revivify the commercial housing market. And since residential housing, along with automobiles, was a major driver of the economy in the 1920s, it’s not surprising that people like Roosevelt thought, “We need to get the commercial housing market working again.”

It’s sometimes not appreciated how much of a fiscal conservative Roosevelt was. Many of the people around him might have been more amenable to a directly financed program of home building. But Roosevelt was very interested in setting up programs that didn’t show up on the budget, that worked indirectly. And the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which was set in motion very early, was very effective at doing just that.

The modern housing program would not have made sense to him, and he wasn’t that gung ho about the PWA. He had very conventional ideas about housing, in many ways not that different from Herbert Hoover. But he relied on Ickes, very much trusted him, and very much wanted to keep him happy, and he was willing to go along.

One key piece of that early New Deal political context that you highlight is that the Housing Division was able to get off the ground in significant part because the real estate capitalists who had always opposed public housing were back on their heels and were in no shape economically — and thus politically — to challenge it.

Yes, one of the things that happened, though, as a result of reforms that were made in the 1930s — HOLC, FHA, Fannie Mae (FNMA) — was that those programs stabilized the real estate industry, and by the end of the ’30s it started picking up steam.

So the government actually built up the political power of this sector through these programs, and it meant that although the PWA didn’t run into such strong headwinds, by the time we get to the later ’30s and a program for American-style public housing — what we call public housing — was proposed, the real estate industry had been revivified to the point that there was a lot of opposition, and it had a big impact on creating a very constrained program.

Labor and the Promise of Public Housing

In 1933, the American Federation of Hosiery Workers immediately jumped at the Housing Division’s offer of loans to build affordable housing and went on to construct this development in Northeast Philadelphia called the Carl Mackley Houses, a project that we’ll talk about more in a moment. But first, how did these Philadelphia labor radicals get turned on to the idea of social housing, and what made unions like the Hosiery Workers — and also the New York–based Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, a much larger union — so interested in challenging capitalist control over the economy and in the organization of everyday life and consumption?

Yeah, partially because they too were influenced by the European mass-housing movement, knew about it, and had traveled to Europe and seen some of these developments.

And like Bauer, they were quite entranced and talked it up to people — the idea that through cooperative enterprises, ordinary people would have control of more of their lives, could be shielded from the market. These kinds of ideas that we might call social democratic — they were just part of the conversation in left union circles at that time.

Out of the hosiery workers union came the Labor Housing Conference, and the idea was to make projects like the Mackley Houses part of an amply funded, large-scale, nationwide social housing program, something larger and more permanent than the Housing Division. Bauer took up the leadership of the organization, and she immediately set about converting organized labor to its agenda, which was no small task. Despite these left labor currents that we’ve been discussing, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) had declared in 1932 that government-sponsored housing was against American “ideals of individual initiatives and rights.”

What was the Labor Housing Conference, and how did it bring labor over to its vision? And then what role did it envision unions having in an American social housing system?

The Labor Housing Conference was a really marginal operation consisting of Bauer, Stonorov, and some allies in the labor movement. The challenge, as you indicate, was that a lot of American labor was quite conservative. But as the housing and building crisis mounted, people in the traditionally very conservative construction segment of the labor movement become more amenable to ideas about government-funded construction projects.

If they had more time before World War II, before the pro-commercial housing programs of the New Deal had taken hold, it’s possible that the backing of the labor movement — which grew over time — might have been able to push things more in a direction of the modern housing conception for policy. But the window of opportunity closed.

Now, what were the hopes of the modern houses when it came to labor? One was that federal policy would make it possible for organized groups in civil society — mainly labor unions, but also cooperatives of other types — to come to a federal housing agency and get low-cost capital to build noncommercial projects of the kind they wanted, in the kind of place they lived, and in which they would have a lot of input into the design, and that this kind of active, grassroots energy would connect with a nationally coordinated program. And for them the obvious seedbed for this was the labor movement.

You write: “That some moderate-income people not only found PWA housing appealing but were allowed to move in points to one of the best features of the PWA program in its first years: that it was not means tested.” I think it’s hard for many people today to understand why the government should be building housing for people who are not poor, though building housing for the majority is precisely what social housing is all about.

Why did the Labor Housing Conference see public housing becoming a relatively universal program as so crucial? What was the group’s vision of the place for state-built, state-funded, or state-coordinated noncommercial housing in the larger housing market?

To respond to your first question: Why did they see it as so important? I think it can just go back to the old social work saying, which is that policies that are aimed specifically at poor people end up poor policies. And that’s because the poor, by themselves, are not a powerful constituency. They don’t have the political weight to get things for themselves, by themselves.

In the 1980s, when the Reagan administration came into power, it was set on cutting back social programs. And there was pushback across the board for a number of these efforts. Funding was restored in many areas. But the place that the extreme cutbacks happened was public housing, housing vouchers, etc. Something like 80 or 90 percent of federal funding was withdrawn from housing programs.

On the other hand, programs that cover the majority of people in this country, what policy scholars called universalist programs, have a lot of resilience politically. The poster child for this is Social Security, which was established in the 1930s: although it comes under pressure, it continues as the so-called third rail of American politics.

So the Labor Housing Conference’s concept was partially based on an idea of creating a powerful political constituency that would maintain this program over time, but it also had to do with a vision of better patterns of urban growth. It wanted to replace this speculative, sprawling, low-density, formless building pattern that was starting to take shape with large-scale, comprehensively planned urban regions with walkable neighborhoods. And the Conference felt that this would be not just a cheaper way to build, but it would be a more supportive and satisfying context for people’s lives.

You write, “The real problem with private ownership was that it seemed to reinforce the privatism that characterized US political culture.” What was the Labor Housing Conference’s vision for a new housing system leading to the creation of new social realities and new forms of political consciousness? Because the dominant New Deal housing framework was achieved through support for the private mortgage market via the FHA, that ends up creating a very different sort of political subjectivity, a political subjectivity that, rather than guaranteeing a permanent Democratic majority (which was Roosevelt’s aim), lays the groundwork for quite the opposite. What sort of political subjectivity and forms of sociality do the Labor Housing Conference see a social housing system helping to facilitate?

Its plan was designed neighborhoods where there were social facilities, places for people to meet in formal and informal ways that depended on these more compact residential areas — people could walk to things rather than using automobiles all the time.

In the vision of the hosiery workers — specifically the housing project they sponsored, the Mackley Houses — the nursery school was the part of it that integrated people and got them working together and getting to know each other. The nursery school was extremely well run. People from outside the complex brought their children, some professional people, and it was a place where people volunteered to help mothers. It was also a place where the residents got together to support each other. It never really ran on its own in an easy way financially. And so the mothers would get together and have rummage sales and bake sales and various kinds of entertainments to make money for the nursery school. It sounds kind of laborious keeping this thing afloat, but everybody who was connected to it said that it was the best thing about the complex, because it meant that they got to meet other families and create these bonds.

So in terms of that vision of sociability that you were asking about, I think the nursery school represents that really well.

The socialization of socially reproductive labor.

Yeah, exactly. And it just happened kind of organically. It wasn’t forced on people.

Yeah, the Mackley Houses, which opened in 1935, were really intended to foster a certain sort of community and even left-wing political life. But it seems that mostly, with the strong exception of the nursery, residents just thought the development was a nice place to live, not a utopian experiment.

Right. In retrospect, there might have been more things the union leadership might have done to communicate these ideas to people. But they didn’t have the capacity to do that at the time. They were under terrific pressure in other areas and didn’t have extra people to do educational outreach.

This was one of the things Bauer was concerned about in terms of publicizing these ideas so that people would start asking for them, asking for a new kind of housing, and would move into new kinds of housing already excited about the possibilities that this would offer. But there wasn’t a common knowledge of these kinds of alternatives in the United States at this moment.

You just mentioned that the hosiery workers might have been able to more intensively program and support different sorts of community life within the Mackley Houses. But the workers were under such incredible stress, being a militant union in a rapidly declining industry, and indeed the very economic realities of constructing the Mackley Houses with PWA support made them too expensive for hosiery workers to rent.

Yes, which was a big disappointment. But it does point to the fact that it was possible to build housing for the middle, and have people, even professional people, schoolteachers, move into this situation because they could see all the opportunities that were there: the swimming pool, the meeting room.

Balconies.

Yes, it was expensive, but more expensive than they wanted. Part of that was that they weren’t given capital as cheaply as the federal government could have done. And had the place been subsidized a little more at the beginning in terms of capital costs, the rents could have been kept a lot lower.

Cutting Public Housing Short

Or they could have had a more diverse mix of rents so that at least some substantial portion of the units were renting at a lower level.

We’re not at 1937 yet, at the point where the PWA’s Housing Division, a temporary program, is supplanted by the Housing Act’s permanent public housing program. But what was it during the life of the Housing Division that circumscribed its scope and scale so that not only were there not more Mackley Houses, but the Mackley Houses could not be as affordable as they needed to be to accomplish their mission?

There’s two issues that speak to this question. One is that Ickes, who was in charge, was interested in creating a corporate subsidiary, an authority structure that was legally independent of the government agency, and could function flexibly in the market. Roosevelt backed him and even committed something like $100 million to fight to capitalize this mechanism that Ickes wanted. But the controller of the treasury was an appointee of Hoover’s, and there was no way to remove him until his term ended. And he refused to transfer the money.

So Ickes had to work through the vehicle of the Housing Division, which was much clunkier and slowed everything down. Added to that, he faced the problem of trying to put together places to build. And here is one area where the direction of his conception of the best direction to go really diverged from the modern housing proponents.

This is the question of slum clearance versus greenfield development.

Yes, exactly. And whatever the abstract merits of greenfield development — which he might have even agreed with — he felt that politically to keep support coming, especially for something as radical as direct federal intervention into the housing market to produce housing, he had to respond to all the people who thought they should be doing slum clearance. But the problem was that slum property was divided up between many owners (some of whom had died decades before) and organizations that had ceased to exist. Managing to buy up property so that there would be large areas for construction was a nightmare. Toward the end, the only thing to finish off the job would be to condemn land and use eminent domain.

But this path was blocked as well because the courts wouldn’t go along. And when two layers of the federal courts ruled against him, the only option he had was to go to the Supreme Court, which was quite conservative still at this point. Roosevelt was afraid that a major ruling against this would threaten some of his other programs. So Ickes at that point was stuck with the option of getting local organizations, housing authorities, to condemn property. And the courts went along with that.

But all of this took a lot of time, and it meant that Ickes had to just wait. We know that, looking back, many communities never organized a housing authority, never asked for help setting up low-cost housing, low-rent housing for the poor people in their area. They kept them out in the first place by zoning rules, or they ignored them. And places that did have housing authorities, they were often dominated by local businessmen, many of whom were real estate speculators themselves.

Even though there wasn’t any building happening during the 1930s, they had their eyes on the edge of growth: the greenfields that you talked about. They wanted to keep those available for themselves when the market picked up. And so they, too, emphasized slum clearance over greenfield development to the local housing authorities.

Which is interesting, given that American public housing soon thereafter becomes fundamentally intertwined with slum clearance throughout much of the twentieth century.

Yes. And real estate owners liked this because it meant that areas were cleaned up at taxpayer expense, and private developers’ properties gained value. Or else they got this cleaned-up area themselves to build on.

For much of the twentieth century, we thought of public housing as federally funded, but built and run by local public housing authorities. Then, since the destruction of public housing commenced, arguably, in the 1980s, we have thought not so much about public housing — though plenty still exists — but more “affordable housing,” built in large part by nonprofit community development corporations using federal tax credits.

What forms of centralization and decentralization between various forms of government and nonprofit entities and labor unions did Bauer and the Labor Housing Conference envision?

Bauer and her colleagues and the people in the Labor Housing Conference imagined that organized groups would have the ability to get support from federal programs to build housing that they envisioned as meeting their needs. And it wouldn’t be a kind of cookie-cutter, one-size-fits-all federal program. There would be a range of cooperatives and labor unions.

In some way, you might think that, well, this is like the community development corporations (CDCs) of today. But their vision was different than the CDC’s in that they thought of these groups that would organize to get loans and technical assistance from the federal government. These would be people who would be living in the housing themselves and not just nonprofit developers who were doing it for them. And so there’d be a much more democratic grassroots flavor to the program.

Yeah, that’s interesting, because in their vision, the federal government would have played a much larger role. But at the grassroots, the program would simultaneously be far less state-centric.

Yes. That was something that Bauer tried to get written into the permanent legislation, but wasn’t successful.

An Example in Harlem

We got the worst of the state and non-state roles possible in the end.

The other major example of housing in your book, alongside the Mackley Houses, are the Harlem River Houses, built for black people specifically. They were constructed by the Housing Division after it shifted from indirectly subsidizing groups like the hosiery workers building housing to directly developing housing. And it was a very nice project and is still considered so today. It’s what we might have wanted out of a social housing system in America: lots and lots of Harlem River Houses.

But before we get to the development itself, can you lay out the context of what led to it getting built? What housing conditions prevailed at the time in Harlem? What sort of black militancy around housing emerged in response to those conditions? And why did other ventures fail to provide a solution?

Harlem is a fascinating case of investor catastrophe. This part of Manhattan seemed, to real estate investors large and small in the early part of the twentieth century, to be perfect for luxury housing. And they built a lot of it, only to find that the swarms of wealthy families they had counted on didn’t materialize. Because they were left empty-handed and desperate for revenue, they were willing to offer housing to black families in a way that most property owners weren’t at the time.

And black people did move into Harlem in great numbers. The housing available wasn’t ideal because they couldn’t support these very fancy apartments and brownstones that had been built, so the places were cut up into tiny pieces. It looked good if you were walking along the street.

Gorgeous brownstones.

Yes, but people were crowded into them, and there was a lot of suffering that didn’t meet the eye. And there were tenants organizations formed, ones that were led by more mainstream, black professionals, but also ones that were influenced and connected with the Communist Party. They spent a lot of time educating people, essentially, and they did a lot to promote grassroots militancy and sponsored demonstrations and various events to publicize the idea that the government needed to respond to the terrible housing situation in Manhattan, and specifically in Harlem.

Going back to what we talked about in terms of the Mackley Houses and how a lot of the people who came in did it on the basis that it just looked like a nice apartment, and they hadn’t really been educated about the American housing problem in general — in the 1930s in Harlem, this tenant organizing did the education about how they could have better housing options. When the Harlem River Houses finally opened, the people that came in were poor, but they were fairly sophisticated about how the government needed to relate to housing from their standpoint, with their interests in mind.

But you ask about other elite responses to the Harlem housing problem. The one that stands out is efforts by philanthropists and conservative elites from the late nineteenth century onward to develop housing that would be affordable to poor people within the capitalist market system. The best example of this was the Paul Laurence Dunbar Garden Apartments that were developed by Rockefeller — not the senior Rockefeller, but his son, who loved architecture and was the money behind restoring Colonial Williamsburg and Radio City Music Hall. He got it into his head that he would build housing in Harlem that would be entirely within the private sector.

He hadn’t made any of his fortune himself, but was very dedicated to proving that the private sector could solve the housing crisis.

That’s right. It’s quite amazing. The state of New York had passed a law that meant if you were a company that agreed to keep your profits down, you could get tax abatements. But Rockefeller, as you say, was very anxious to prove that this could all be done without any government intervention whatsoever. He didn’t take those, and he hired an architect who designed a lovely building.

And of course, the ultimate cost was more than was imagined at the beginning, so the rents were higher than he had hoped. The most affluent black Americans who lived in Harlem moved in, and the place was terrific for a little while until the economy crashed. Pretty soon the whole financial structure that Rockefeller had set up collapsed. But he had hopes that this would be a great success and he would expand it. So just on spec, he had purchased a big area that was unbuilt in Harlem, not too far from the apartments.

And it was the fact that that land was sitting there at the point that the PWA Housing Division was set up that made black Harlemites think that the government should do something to use that land productively and create housing. And that’s what I mean about people becoming conscious that there were alternatives, and that they could live better if they had government support to supply them with high-quality housing. They came to the Harlem River Houses when they were opened with that sense in mind, so they had this vision that never got created in Philadelphia.

As an aside, I think one key thing about creating mixed-income public developers today, even if at the beginning they don’t have sufficient subsidies to build as much or as affordably as we would hope, is that just creating the capacity for the state to build housing for anyone creates the possibility of posing a political demand for housing to the state.

There’s a housing crisis right now, and it’s not in the popular consciousness at present that the state is an entity upon which you could make a demand around housing. So people are pissed off, but they go to the state and say, we’re upset about the housing crisis and politicians say, something something affordable housing, more construction, something, something.

Or we’ll do something to get rid of the homeless people on the sidewalk that are upsetting you and we’ll take them somewhere.

Right? Because people are aware that the state has carceral and repressive institutions that it can unleash. So those demands seem plausible to people.

The Harlem River Houses, again, were considered to be very nice at the time and are still considered to be so today. But they also screened prospective tenants to ensure that applicants were nuclear families of “good character,” and project staff performed a weekly rent collection that included an intrusive apartment inspection. In other words, it was an incredibly paternalistic setup.

The income requirements were also very specific, requiring people to be low income but not so poor that they couldn’t pay the rent. And yet again, this project was and remains today, I believe, truly beloved by its residents. What various, and maybe contradictory, lessons should we learn from Harlem River?

In terms of design, one of the features that everybody loved about it was that it was small enough and low enough to be a real community. It fit in with the neighborhood, even though it was built as a superblock. It was open to the street in a way that didn’t seem to mark it off as something different.

Of course, New York public housing has been more successful than public housing in other big cities where it was built. And a lot of that has to do with the fact that New Yorkers are used to living in apartments. But Harlem River was four and five stories, and it had these very attractive interiors and nearby playing fields for older children and gatherings of various types. So it was just a physically appealing place to live. And it wasn’t impersonal. People knew each other. I interviewed people who had lived there as children, and they talked about how they knew other parents. They felt there were always people who were looking out for them, looking after them, and maybe educating them.

Some other lessons about Harlem River: you pointed to the fact that there was this thin group of people who were not too wealthy or not too poor. And the fact that the New York authorities could find enough of these people who fit this very specific image points to the fact that there were thousands of black New Yorkers who needed a place to live. But as time went by, there were pressures on all the housing authorities in the country to orient themselves more toward the very poor, as opposed to the working poor. And some of the original residents weren’t all that thrilled about having people with no regular incomes move in, because some of these families were troubled. They were difficult neighbors. And this points to the various pressures that public authorities have been under over the years.

We haven’t been entirely honest about a preference for the very poor and what that means for the living conditions of more organized families, as well as the income potential of the housing authority, because these folks can’t pay rents enough to keep places operating, and the federal government hasn’t stepped in to really make up the difference — at the same time as it’s required authorities to take more people whose incomes are so low.

Private Over Public

Again, it’s a context of scarcity — a scarcity resulting from politics and the political balance of power and historical contingency that is forced upon public housing authorities. The proposal put forward by Bauer and the Labor Housing Conference was to house everyone but the truly rich.

What were the political fights, coalitions, and debates leading up to the 1937 Wagner-Steagall Housing Act? What was the balance of power between housing advocates ranging from the Labor Housing Conference on the Left to the more mainstream National Public Housing Conference? And critically, where did a revived real estate industry fit into it all?

The thrust of the federal energy around housing had to do with reviving the private industry. Housing was so important for the whole economy, and it provided construction of all kinds. But residential construction, specifically, employed so many people. So the original effort was to stop mass foreclosures and create better opportunities for financing than had existed. That’s where the FHA stepped in, with its indirect program that meant the federal government didn’t seem to be the main actor that it seemed with the FHA. It seemed like that was just the private sector healing itself.

And as that healing took form, this private industry became more confident, in fact. Another piece of the puzzle was the establishment of Fannie Mae, which set up a secondary market for mortgage lenders and made financing more available, cutting interest rates for potential borrowers.

These programs were not aimed at housing the poor. They were aimed at the private real estate market, and they were successful at not only stabilizing it, but also expanding it. Because in the 1920s, middle-income people had a hard time affording housing. But after the financial restructuring of the FHA and Fannie Mae took hold, individual families were able to tap capital markets themselves and get lower-cost loans that meant they were laying out less money.

By the end of the ’30s, it was obvious that the private market was going to be way more successful than it was in the 1920s.

And the idea that there would be a permanent program of federally subsidized housing was anathema to a lot of people who were connected with real estate, and they fought it tooth and nail.

Even the extremely limited, narrowly defined, underfunded one that ultimately passed, they fought that tooth and nail.

Yes, they did. They pared it to the bone as much as they could when the legislation went through Congress. And then after that, they attacked it. To people like us, when we think of how unpopular public housing has been over the course of our lifetimes, we think, “Why were people in private industry worried about this for a second?”

One answer is that any model of government support for production is threatening just because of the example it sets. The other one is, in fact, a secret about public housing just getting us beyond our images of the Pruitt-Igoe apartments in St Louis being blown to smithereens. Public housing isn’t as bad as it has been made out to be. One researcher made the point that everyone hates public housing, except for the people who live there and the people who are trying to live there.

They have waiting lists of years in many places.

That’s right. That’s not to say that residents are happy with exactly how it’s working. They would like changes. They would like more funding. They would like better government. But overall, there’s a surprisingly high rate of satisfaction that housing researchers have found when they’ve surveyed people in public housing.

And all the public housing, despite these stereotypes that we have, is not these bleak high rises. Most of it is garden apartments throughout the country. And it’s something we could build on rather than just turn our backs on. It is something we should save and appreciate and recapitalize as much as we can.

How did the 1937 Housing Act lead to the public housing system that we ultimately got, or at least the one that we did have before it began to be dismantled in the ’80s and ’90s? One critical consequence was that the public housing system that won out over social housing required that construction be done far more cheaply than it was under the Housing Division. So unlike Mackley or Harlem River,

the housing produced under the Wagner Act usually looked unambiguously like poor people’s housing, that it was in fact meant to be. Thus, passage of the Wagner Public Housing Act marked the institutionalization of a two-tier framework for federal intervention into the housing market.

It lent these caps on spending that meant public housing tended to look different a lot of the time, especially in the big cities, and also to be placed in areas that private entrepreneurs weren’t interested in. I think that that aspect is underappreciated, that it wasn’t just the buildings themselves. It was the fact that they were placed in areas that were rundown and not well connected to the rest of the city. The transportation options were poor.

Racially and economically segregated.

Yes. So there was the physical situation of public housing. But also, the fact that it was directly funded made it more obvious what the government had to do with creating it, and made it seem more expensive than it was because the supports that the government had given — and continues to give — to private housing are indirect, so they’re invisible to most people.

The mortgage interest deduction is just one piece of this. Just to give you a sense of the scale of this, mortgage interest deductions — scholars call them tax expenditures — cost the federal government $85 billion. The direct costs for all of our housing programs for poor people cost $50 billion. And that’s just one of the ways we’ve subsidized the private housing market. And this is “tax reform” under Trump, which means a lot less people are itemizing than used to. So the disparity was much greater before the Trump tax cuts.

A major goal of Roosevelt’s housing agenda was to create a materially grounded, permanent constituency for the Democratic Party. But as you write,

over time, the particular character of the New Deal housing settlement has played a major role in undermining a majority coalition in favor of activist government. Given that the mechanisms to reorganize the financial system used by the New Deal housing programs were largely invisible to the average person, many core Democratic constituencies came to believe that they were not receiving any public help. Meanwhile, these groups perceive themselves to be paying for programs to benefit groups they regarded as less hardworking and deserving than themselves. As it worked out then, most Americans came to credit the market and their own efforts for the increase in living standards that occurred after the New Deal.

How did this two-tier American housing system so decisively shape the American twentieth century? And perhaps, if you can allow yourself the speculation, what sort of counterfactual history might we have happened instead, if the Labor Housing Conference’s model had won the fight?

In terms of shaping the politics, it really laid the basis for the Reagan Democrats and the alienation of a lot of middle-income people from the idea of activist government, which they started imagining to be only in support of poor people and racial minorities.

In terms of the possibilities that might have been available had the Labor Housing Conference and its allies been more successful, it seems possible that it could have laid the basis for a better life for a lot of Americans before we even get into their political consciousness.

I grew up in Southern California, which was extraordinarily formless around Los Angeles in the 1950s and ’60s. People would ask me where I was from, and I didn’t have a sense of being from any particular community, because as you drove around, you just drove through more developments that looked like what you just passed. It was just low-density sprawl everywhere. There was no mass transportation to speak of. Everything depended on having a car — the kind of sprawl development where women, particularly, were isolated in their suburban homes.

All this brings out the vision of the Labor Housing Conference — it was not just houses, it was urban design more generally, so that there were more opportunities for sociability and just general convenience. If the kinds of options that Bauer was hoping to get written into the ’37 act had gone through — things like opportunities for co-ops and labor unions to sponsor housing demonstration projects, so that more people could have seen some of these neighborhoods and then would have been able to ask more specifically for something that they didn’t even know existed — it would have led to people thinking of the government supporting them and maybe supporting them better.