No, the GI Bill Did Not Make Racial Inequality Worse

It’s fashionable to say that black veterans got no real benefits from the GI Bill. In truth, for many, the GI Bill was a rare positive experience with government that contrasted sharply with the indignities of Jim Crow.

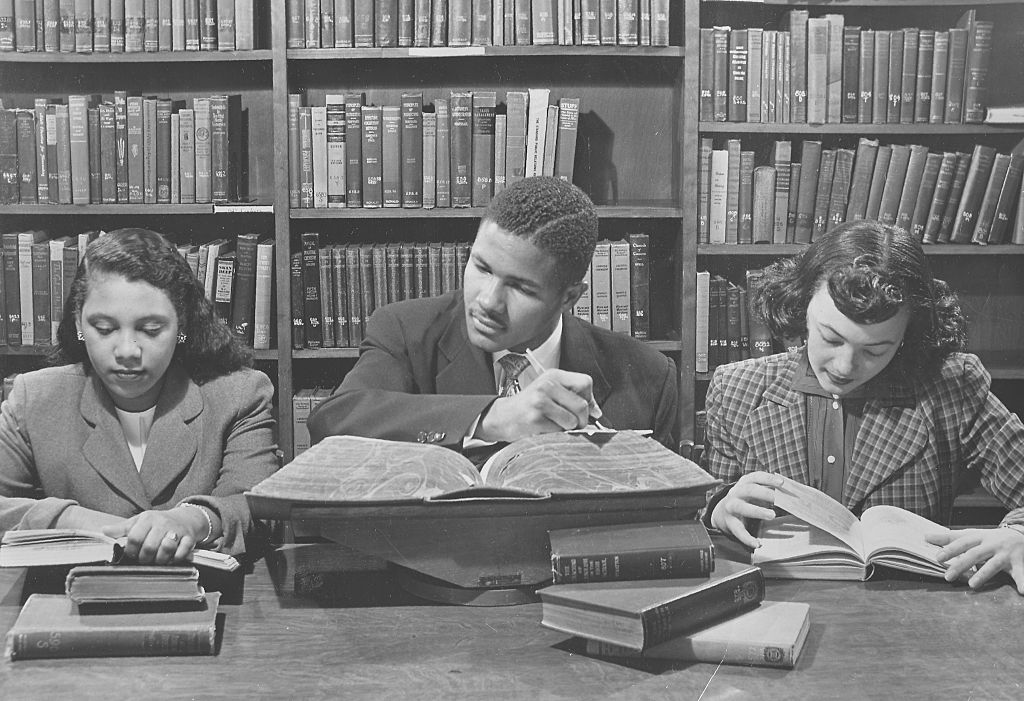

College students at Morgan State University, Baltimore, Maryland, 1955. (Afro American Newspapers / Gado / Getty Images)

Gentry Torian fought bravely with the 92nd Infantry Division, the only all-black infantry division to see combat in Europe during World War II, only to return home to racial discrimination. Reflecting later to his wife, Celeste Torian, he said of postwar America, “The only good thing was the GI Bill.”

“Every black we knew used the GI Bill,” Celeste told political scientist Suzanne Mettler. Gentry used it to fulfill his lifelong dream of becoming a public schoolteacher.

Scores of black veterans across the country had experiences similar to the Torians’. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, popularly known as the GI Bill, offered an exceptionally comprehensive list of benefits to World War II (and later Korean War) veterans. Any veteran with at least ninety days of service and without a dishonorable discharge was eligible. The benefits included unemployment payments of $20 per week for up to one year and low-interest loans to buy a house, farm, or business.

But the GI Bill is perhaps best known for how it transformed higher education in this country. Veterans who served for at least ninety days were guaranteed one year of education or vocational training, with another month added for each additional month of service up to four years. Veterans who used these benefits did not have to pay a dime in tuition costs, and they even received monthly subsistence payments.

It has become a popular trope to insist that black veterans did not benefit in any substantial way from the GI Bill. For example, the famous professor of African American history Henry Louis Gates Jr asserted that the “GI Bill systematically excluded most African Americans” in a recent YouTube video. In early 2022, this historical interpretation of the GI Bill compelled the introduction of a bill that would extend certain GI Bill benefits to surviving spouses and some direct descendents of black World War II veterans.

It is certainly true that there were problems and limitations in the implementation of GI Bill benefits for black veterans. But many of those limitations were a product of a Jim Crow system that predated the bill’s passage. The GI Bill did not create these structural limitations, and the elimination of Jim Crow was always beyond the scope of the legislation’s ability.

A wholesale dismissal of the legislation obscures the fact that black veterans’ experience of the GI Bill was far more nuanced and positive than many critics suggest. Their stories are documented in Suzanne Mettler’s work, including her book Soldiers to Citizens: The G.I. Bill and the Making of the Greatest Generation and her article specifically about black veterans, “The Only Good Thing was the G.I. Bill.”

Interviews with people like Celeste Torian reveal that, for many black veterans and their families, the GI Bill represented an exceptionally positive experience with government that contrasted sharply with the indignities of Jim Crow. To ignore this experience is to discount the role of the expanded welfare state in improving the lives of black Americans in the context of extreme racial inequality.

Black Veterans and the GI Bill

When it came to implementation, the GI Bill fell shortest in its distribution of low-interest home loans. Here, the long-standing discriminatory practices of the real estate industry were the decisive factor.

Though the federal government guaranteed the loan, applicants had to find a bank or lending agency they could use. Local banks often denied loans to black individuals and families. Ebony magazine reported that out of 3,329 VA-backed loans in Mississippi in 1947, only two went to black veterans. One black veteran in a survey testified, “I was required to make a 10 percent down payment because I was told that colored GIs were a bad risk.”

There is no question that black GIs were largely unable to take advantage of the GI Bill’s home loan benefits. However, black veterans’ experience with the educational benefits of the GI Bill were much more positive.

Too often, scholars have used a narrow framework through which to evaluate the usage of GI Bill benefits. Several academic papers have asserted that the educational inequality between blacks and whites was worsened due to the GI Bill. But that conclusion can only be sustained if one focuses exclusively on college attendance and graduation. This perspective fails to take into account both inequalities that predated the GI Bill and the full scope of educational benefits offered.

By the end of World War II, only 17 percent of black soldiers had graduated from high school, compared to 41 percent of white soldiers. Clearly, black veterans were not as well-positioned to use the benefits for college education as their white counterparts. Most black veterans utilized the GI Bill for vocational training and other noncollege programs. Overall, 3.5 million veterans gained vocational training through the GI Bill, causing the number of trade schools in the country to triple.

When taking into account the full range of GI Bill benefits, black veterans actually made use of them at a higher rate than white veterans. A 1950 Veterans Affairs study found that 49 percent of nonwhite veterans had used the benefits, compared to 43 percent of white veterans. Surprisingly, black veteran usage was higher even in the Jim Crow South: 56 percent of nonwhite Southern veterans had used the GI Bill by 1950, compared to 50 percent of white veterans.

In the North, widespread usage of the GI Bill by black veterans advanced the desegregation of institutions of higher education in the early postwar period. Black veteran Reginald Wilson remembered that one-third of the veterans at his alma mater Wayne State University were black at the time he attended.

Tuskegee Airman Henry Harvey used the GI Bill to attend Northwestern University. In an interview with Mettler, he reflected that, without the GI Bill, “I possibly would have continued my education, but it would have been at a local junior college . . . where the tuition was $60 a semester. . . . So there’s a possibility I would have gone to college, but it would have taken much longer.”

In the Jim Crow South, the choices for black veterans were more limited due to the segregation of higher education. Again, this was not an effect of the GI Bill but a preexisting practice that the GI Bill itself could not remedy.

Even as all-white colleges kept black veterans out, historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) like Howard University, Morgan State University, Morehouse College, and more greatly expanded due to the increased demand. Between 1946 and 1947, overall enrollment at colleges and universities increased by 13 percent, but enrollment at HBCUs expanded by 26 percent.

While the expansion of HBCUs could be seen as positive, the manner in which it took place during this period was not ideal. Already underfunded, HBCUs did not have the proper resources to absorb this increased enrollment. Many students reported overcrowded classrooms and inadequate living conditions. Nevertheless, while the GI Bill did not overturn educational inequality in the South, it did dramatically increase educational opportunities for African Americans.

Available data suggests that the GI Bill may have been even more meaningful to black veterans than to white veterans, perhaps because it stood out so sharply from the discrimination they experienced in other areas of life. In a World War II veterans survey, 92 percent of black higher education beneficiaries and 89 percent of black noncollege beneficiaries in the 92nd Infantry Division considered the bill a turning point in their lives. Only 78 percent of white higher education beneficiaries and 58 percent of white noncollege beneficiaries said the same.

In Mettler’s countless interviews and testimonials, black veterans from the 92nd Infantry Division detailed the many ways the GI Bill acted as a positive force in their lives. One beneficiary claimed that the program “broadened my scope of knowledge, made me hireable, interesting; increased my friendships, which now, fifty years later, still permeate my life.”

Others said the GI Bill “helped me get a job with General Motors,” “gave me a chance to try other venues of work,” or simply “helped me make a decent living for my family.” These accounts from black veterans themselves need to be fully taken into account when considering the effects of the GI Bill.

The GI Bill and Civil Rights Activism

Mettler goes further than just asserting that the GI Bill was a positive experience for most black veterans. She also makes a compelling argument that the program helped boost civic engagement and civil rights activism among its beneficiaries.

Again, the GI Bill could not and did not end Jim Crow. Even after gaining an education using the GI Bill, most black veterans faced fierce discrimination in the job market. But that process itself had an interesting effect: the experience of the GI Bill raised black veterans’ expectations of government, helping throw into sharper relief the gap between the way they were treated and what they knew was possible. Mettler explains:

After the war they encountered the discriminatory job market and social system, but they knew from their G.I. Bill experience that they had the right to be treated on equal terms to other Americans. Thus, their encounter with discrimination at this juncture provoked their political mobilization, as the fundamental unfairness of such treatment became all the more evident and intolerable following experiences that differed so sharply.

Available data supports this assertion. During the height of the civil rights movement, from 1950 to 1974, 35 percent of black GI Bill users participated in protest activities, compared to 8 percent of nonblack GI Bill users. Black GI Bill users were overrepresented in the organizations that were most active in the fight for civil rights, such as the NAACP and Urban League.

Between 1965 and 1979, during the height of new local black governing regimes, 31 percent of black GI Bill users were involved in local government compared to 4 percent of black nonusers. Black veterans were also very active in fraternities that played an important supporting role during the civil rights movement, such as Alpha Phi Alpha, Omega Psi Phi, and Kappa Alpha Psi.

The story of Hosea Williams is a great example of this dynamic. Williams used the GI Bill to complete high school and then went on to earn a master’s degree in chemistry from Morris Brown College. After getting hired by the US Department of Agriculture as a research chemist, Williams was recruited to serve on the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Martin Luther King Jr’s staff.

NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers used his GI Bill benefits to enroll at Alcorn State University in Mississippi. His college experience prepared him for a life of activism as he became class president, yearbook editor, and student newspaper editor. Most important of all, Evans was exposed to the civil rights movement on campus.

Disputed Legacies

The GI Bill has received much the same treatment in American political discourse as the New Deal. It has become fashionable to simplistically dismiss New Deal social programs as hopelessly racist and unavailable to African Americans. While there is no denying that New Deal benefits were not distributed equally, these historical accounts propagate a wildly misleading picture of how black people actually interacted with the New Deal in its totality.

In the context of a thoroughly racist society, the New Deal represented a significant step forward for many black working people. As scholars like Adolph Reed have tirelessly pointed out, blacks were overrepresented in many New Deal programs like the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps, where black workers made up a larger share than their percentage in the overall population.

Far from an abstract academic debate, cynical and inaccurate depictions of the New Deal have been used to try to discredit both of Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaigns and the overall growing social democratic tendency in US politics. There is a similar danger in ignoring the complexity of black Americans’ experience with the GI Bill.

A more accurate and nuanced appreciation of the GI Bill’s usage among black veterans is needed. The program’s large-scale success should give us hope that governance for the public good is possible again for all working people, regardless of their race.