Nurses at Two New York City Hospitals Just Won Historic Strike Victories

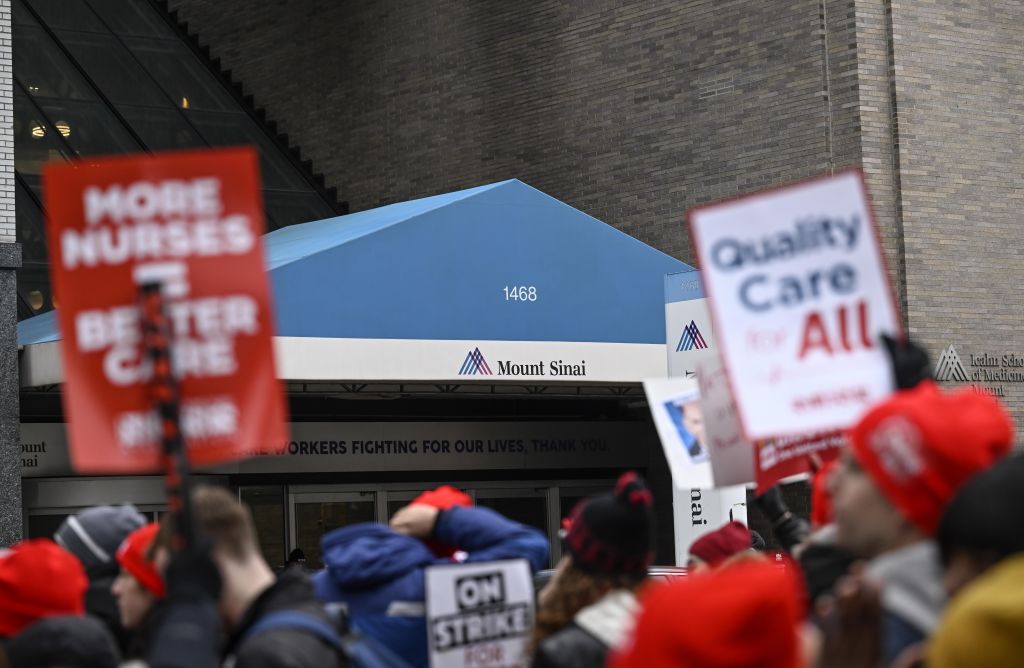

This week, 7,000 nurses at Montefiore Medical Center and Mount Sinai Hospital walked out and won significant victories on patient-staff ratios. Jacobin spoke with striking nurses at both hospitals.

Nurses from Montefiore Medical Center picket in front of their workplace during their strike on Tuesday in the Bronx. (Selcuk Acar / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Sara Wexler

On Monday, January 9, seven thousand nurses at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx and Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City walked out after negotiations over new contracts had stalled. The central demand of nurses at both hospitals, represented by the New York State Nurses Association (NYSNA), was enforcement of safe staffing levels. The nurses complained that the hospitals’ failure to ensure adequate staffing was lowering the quality of care and endangering patients.

Early this morning, NYSNA reached tentative agreements with both hospitals, ending the strike. Nurses won safe staffing ratios as well as language ensuring that the ratios will actually be enforced. Jacobin’s Sara Wexler spoke with nurses at Montefiore and Mount Sinai about the strike and the tentative agreements.

We have a three-year contract. So there’s really no break; we’re always trying to organize and look to the next one. But what we were really worried about at Sinai is safe staffing. This is something that’s gotten worse. It existed far before the pandemic and it only got worse with it. We would go to management every day, in every unit all over the hospital, voicing our concerns, and nothing was ever done.

The strike was about our patients. Nurses and health care workers in general are working in really terrible conditions. Anyone who you talk to, whether it’s a nurse or respiratory therapist or even a doctor, is complaining about our patient loads. What that means is that we have too many patients who need to be seen or too many patients who are very, very sick assigned to us.

With our ability to advocate with our union, we have been telling the institution for the past three years since COVID that we are short; it seems to have fallen on deaf ears. For the last three months, we have tried to negotiate in good faith and explain to the hospital why our staffing-enforcement language was so important to us, why our ratios are so important to us. But unfortunately, it never responded to us. That’s why we had to make this decision that we did, to go on strike.

It was really about safe staffing. At this point, everybody talks about the wages, and the wages were of course a factor. Before the strike, Mount Sinai made less than any other private New York City hospital, and before the strike, we were over five hundred nursing vacancies short. So we’re doubling, tripling up on our patient load. But beyond that is the safe staffing levels. A lot of us have said it doesn’t matter if they increase our pay or double our pay, because it’s not worth it. It’s really about having better staffing in the entire hospital.

Could you tell me more about the patient-staff ratios?

As an ICU nurse, I’m supposed to have either a one-to-one or a one-to-two patient assignment. What that means is I, as one nurse, should never have more than two patients. There’s a reason, because when we are taking care of our ICU patients, or some of the sickest patients in the hospital, these patients can deteriorate in seconds right in front of your eyes. If you are not available to give them the time or the assessments that they need, and then the rapid interventions that they need, it causes delays in care, which we know affect their outcomes and their prognosis.

I think the most patients I’ve had was twenty or so. I really can’t put this into words, but you’re talking about a war zone. Patients are pretty much on top of each other, there’s no way of isolating them — you have a ninety-five-year-old elderly woman who’s out in the middle of the ER for a day or two days before she can get admitted. It’s really horrific.

As an ER nurse, I love what I do. But it has turned into me just chasing my tail and trying to complete orders. I don’t really have time to be a nurse. Patients will get pissed; they’ll get mad at me because they see me the most as a nurse; you have people yelling at you about how nobody’s giving them updates. They feel like they’re neglected. It’s a terrible feeling. Because that’s not what this is about — we want to take care of our patients, we want to make them feel better in every aspect. But we can’t.

What were the nurses’ concrete demands? And do you think those demands were met in the tentative agreement?

One of the things that nurses asked for is for a penalty when we are short-staffed. That’s what we’re calling our staffing enforcement language. I think the nurses of this institution are very demoralized by being short every single day. And the institution has told us so many different times that they’re trying to find nurses. But it’s a question of, “Are you really trying to find nurses? Or are you not?”

Another concrete demand was an end to hallway patients. In my institution in the Bronx, Montefiore, we have what are known as hallway beds, which means that when the hospital has “too many” patients, they place patients in the hallway. There is nothing dignified about being placed in a hallway — you do not have the ability to turn off the lights; you’re not going to get too much sleep, because the lights are on the whole night and it’s loud in the hallways.

Those were the baby problems. But the heavy problems of having hallway patients include the fact that it’s a safety risk to both the patient and to the provider. A patient comes up to the floor when they get their negative flu test, and then, a few days later, they’re flu-positive, and they have exposed everyone who has been in that hallway.

Emergency department (ED) ratios was another concrete demand. We have been asking for ED ratios for a very long time. Our institution had told us that it would never agree to our emergency-room ratios. After we placed strike notice, their tune changed.

I’m excited about the language that we were able to negotiate for the nurses. It’s language that the hospital said that they would never, ever agree to. That language includes a financial penalty for the hospital when nurses are short. One of the most important things to us has always been staffing enforcement. By now, having the language and the contract to fight back, we are going to make sure that we bring in more nurses.

We also were able to negotiate a graduate nurse program, which means that we’re going to be bringing in at least thirty to sixty new nurses a year through a graduate nurse program, which is going to be attached with tuition reimbursement. The nurses can be reimbursed for up to $10,000 to $15,000 over three years. This is going to be a way for us to recruit and retain and bring in new nurses. This is going to positively affect our community and patients, because when we have more nurses, we can deliver better care.

In the tentative agreement, we won staffing ratios, which was the biggest topic on the table, and the subject that management gave us the most pushback on. Each of these ratios were selected by the units with the executive committee and designated strike captains who were able to advocate for each unit’s specific needs. The hospital will accrue a fine each time the ratios are broken. This will really force the hospital to hire more nurses, and hopefully retain them as well.

We also won salary increases — Mount Sinai will have the highest educational differential of all the NYC hospitals. We also won improved health benefits and retiree health, which were some of the other demands we had.

I cannot express how much of a difference it will make with staffing ratios. And we won ED ratios, which is enormous, because the hospital had been dead set against ED ratios specifically. But the fact that we have an enforceable limit on the number of patients to care for at once is 100 percent life-changing, literally and figuratively. I think I will actually be able to go home and sleep at night, knowing that I was able to provide quality care for my patients.

These hospitals totally underestimated us nurses. We called their bluff. We refused to back down and stood in solidarity on the picket lines. I’m confident that this will lay the groundwork for putting staffing ratios in place in more states across the country.

Did the hospital try to bring in replacement labor during the strike?

Yes! There’s all sorts of talk of the ER having twenty-three to twenty-five patients, even with scab nurses. Same thing at Montefiore: on their floors, travel nurses were quitting themselves. They were saying, “I’m about to go outside on the picket lines with them. I get why they’re striking.” They had doctors, physician assistants — people that were nonunion — forcing them to fulfill those roles. It’s very sad, because the hospital knew this; they had ten days to prepare for this strike. And they weren’t prepared.

How did it feel to be on strike?

This has been a phenomenal victory for us as nurses, because for so long, we have sat here and heard our institution call us “health care heroes,” and then we dealt with the last few years, when none of us have felt like we were getting the dignity or respect that we deserve as workers. When we went out to the streets, it felt like we were telling the hospital, all the CEOs, that we are not going to continue working under the conditions that you are providing for us. We’re going to continue to fight for better for ourselves and for our patients.

No worker deserves to work in conditions where they go home at night and can’t sleep. I’m proud of us for taking that stand. Because we took that stand not just for ourselves but to improve the care that our patients are receiving. There’s something really dignified about people standing up against injustice.

Rejuvenating, satisfying. It’s still obviously anxiety-provoking. I was at the picket lines every day. I was actually supposed to start a nursing contract on Monday at a totally different place. But I canceled this contract because I was like, “I need to be here.”

This is what I’ve been fighting for the last six years. I was a month into orientation at Sinai when I realized something wasn’t right. So it’s incredibly empowering. Seeing us nurses together with such a strong workforce — being all outside together and seeing how strong we are is something amazing.

Montefiore has a history and reputation of being pretty badass. Their division of NYSNA is very strong and almost militant. However, Mount Sinai’s in the past hasn’t been as much. So I think Mount Sinai management totally underestimated us. It feels pretty damn good.

How has the strike affected the relationships between you and your colleagues?

This whole past year has been us getting more and more united. Throughout the process of negotiations, people had the opportunity to hear how management speaks about certain things. For instance, when we talk about staffing, management will say that they need more flexibility from nurses, which . . . I already have seven or eight patients; how much more flexible do you want me to be? Where’s the flexibility from the institution to say, “We’re going to hire more nurses”?

I think a lot of nurses in this process have learned that the administration doesn’t really care about any of us. That’s been clear through this three- or four-month-long process of negotiating. That’s also how we were able to build collective power to get where we are today. It has definitely brought us all together.

We’ve always told our nurses that if the conditions at the hospital were different, all of us and our different areas would have a lot fewer problems. For instance, our emergency rooms are overcrowded. So the emergency room sends the hallway patient up to the floor nurse, and then the floor nurse is miserable, because now they have a hallway patient that none of us feel is appropriate for the hallway. It creates this divide between people. But this process has allowed them to see that it is not we who are creating these situations. We have to work with each other to build and to push back. We see that there’s a systemic issue here. We’re not going to let that systemic issue divide us. Rather, we’re gonna unite ourselves so that we get better standards for both our emergency room patients and for our patients who are upstairs. And that’s what we did in this strike.

Can you tell me when and how the organizing started around the strike?