What Eugene Debs and the Socialist Party Can Teach Us About Freedom

Jeff Bezos wants us to believe that allowing billionaires to wield enormous power makes us all better off. Eugene Debs and the Socialist Party, founded 120 years ago this summer, had a very different vision for society: one of empowered workers and freedom from domination.

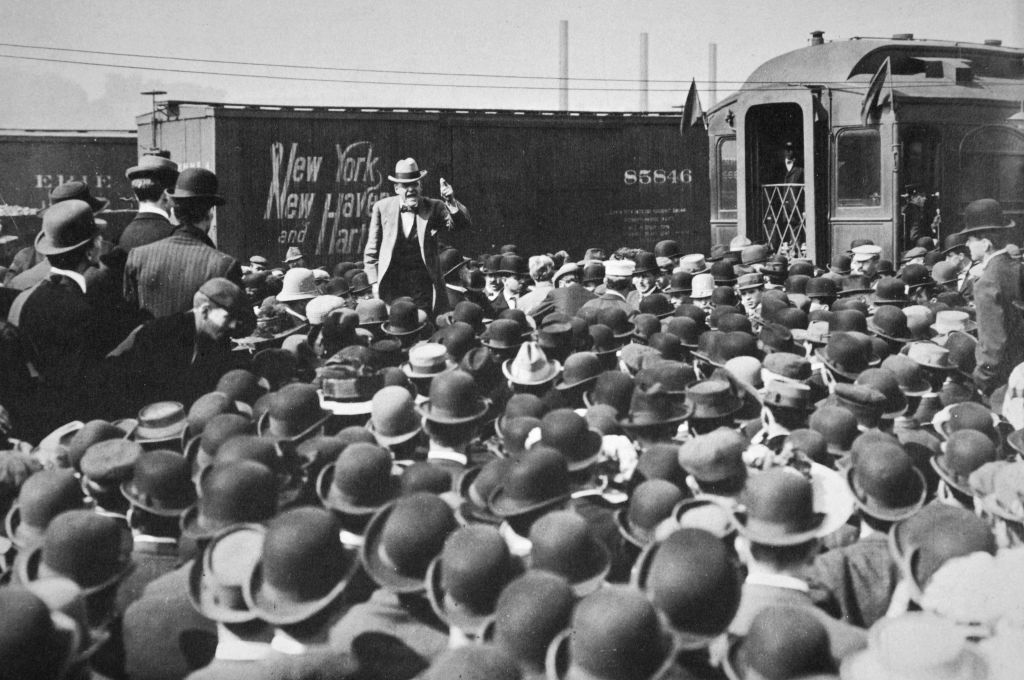

Socialist Party of America leader and five-time presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs addresses a crowd. (Historica Graphica Collection / Heritage Images / Getty Images)

Just call it the summer of billionaires.

In July 2021, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson preened for the cameras before blasting off into space, beating fellow billionaire Elon Musk to the punch. In separate trips, the two peered down at the blue planet, suspended above us mere mortals, experiencing weightlessness for an ethereal few minutes. It was “the best day ever,” enthused Bezos, he of the $190 billion net worth. Musk, perhaps nursing a bruised ego, salvaged the summer by winning a $3 billion contract from NASA over the howls of Bezos’s space-exploration company, Blue Origin.

Workers, meanwhile, have been consumed by more prosaic concerns this summer: Fear of eviction. A deadly new coronavirus variant. Lethal heat waves, floods, and wildfires.

This disconnect — workers struggling to get by, the uber-rich struggling to get to another planet — sums up our new Gilded Age, where the organizing principle seems to be that granting the rich extraordinary say over our economic, political, and social life will ultimately benefit the rest of us. As Bezos acknowledged in his most recent letter to shareholders, he considers Amazon and himself the true wellspring of social value — the rightful rulers of the world, in so many words.

But is this really all we can hope for? To cheer on the billionaires from the launchpad, clapping like seals while we earnestly await what they might bequeath to us next?

Another summer, 120 years ago, a radical new party laid out a very different view of what fosters freedom and human flourishing. The organization: the Socialist Party of America. Its standard bearer: Eugene V. Debs.

“The capital of the country is held in the hands of a few,” Debs declared that summer on the Fourth of July, speaking at a park in Chicago. “And these few, though untitled and uncrowned, wield greater power than crowned kings and despots.”

He may as well have been talking about Jeff Bezos and company. In Debs’s eyes, and the eyes of many socialists of the day, the rise of industrial capitalism had spawned a new form of bondage, where workers toiled for bosses and plutocrats controlled the political system. The sovereignty of the people — that democratic dream of the dispossessed since the French and Haitian revolutions — had been dipped in the acid bath of capitalism and come out a disfigured, mutilated effigy.

Later that month, on July 29, 1901, delegates gathered in a four-story hall in Indianapolis, Indiana, and formed the Socialist Party of America. Their cause — dethroning the Bezoses of their day and empowering ordinary workers — proved surprisingly successful in the laissez-faire United States. By 1912, party membership had soared to 113,000 (from less than 20,000 in 1904), and Socialists boasted hundreds of elected officials across the country. In Western mining camps, midsize industrial towns, and immigrant working-class districts in major cities such as Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and New York City, scores flocked to the Socialist banner. Oklahoma Socialists built the strongest state party in the nation (attracting tenant farmers by the thousands), and Socialist newspapers honeycombed the country (led by the folksy Kansas-based Appeal to Reason, whose peak circulation reached 760,000).

For the party’s poor and working-class supporters, the Socialists explained why their lives were often-dispiriting trials of toil, hardship, and humiliation. The problem, according to the party, was the despotism of capitalism: the system turned workers into bosses’ underlings — forced to work or starve — and made the political arena a fetid square of ravenous corporations and bought-and-paid-for politicians. They proposed an array of immediate reforms (from the eight-hour-day and unemployment insurance to public ownership of major industries and equal voting rights for African Americans and women), while advocating, in the long term, a “cooperative commonwealth,” where the economy would be democratically controlled and the political system would be rid of plutocrats.

Freedom was central to that vision. “As long as he owns your tools he owns your job,” Debs told a labor convention in 1908, referring to employers:

[And] if he owns your job he is the master of your fate. You are in no sense a free man. . . . You will never be free . . . until you are the master of the tools you work with, and when you are you can freely work without the consent of any master.

This radical view of freedom was popular in working-class circles in Debs’s day, part of the “republican” political tradition that scholars have excavated in recent decades. Originating in ancient Greece, republicanism sees freedom as “non-domination” — freedom from arbitrary rule. In its socialist guise, republicanism seeks freedom from the caprices of the boss and pushes for democratic control in political, economic, and social life.

Think again about Jeff Bezos: The question for socialists like Debs isn’t whether Bezos acts with occasional benevolence, but whether he wields unaccountable power over his workers and the political system. Bezos would like us to toast the $400 million he donated to charities this summer and eye with glee the impossibly vast inventory of Amazon.com. We’d be better off remembering the Amazon workers forced to pee in bottles because of the company’s frenetic work pace; the pregnant Amazon warehouse worker who miscarried after her bosses refused to give her lighter duty; the company’s intense union-busting campaign against workers in Bessemer, Alabama; Amazon’s public competition for its second headquarters, which saw cities grovel before the company for the chance at investment; and Amazon’s intimation that it would leave Seattle (thus devastating the local economy) if the city council didn’t nix a tax on the rich. Bezos’s world is one of bowed heads and forced servility, the imperious stare of autocrats and the brutalizing hierarchies of capitalist society. It is the antithesis of freedom in the socialist imagination.

The Socialist Party of America peaked around 1912 and plummeted after World War I, done in by ferocious repression (including the jailing of Debs himself for antiwar statements) and ruinous intra-party conflicts. While Socialists could point to a few remaining strongholds in subsequent decades (such as Milwaukee and Bridgeport, Connecticut) and members lent their talents to crucial democratic struggles (the labor movement, the civil rights movement, the feminist movement), the party never regained its early twentieth-century luster.

Yet Debs and the Socialists gifted us a way of thinking and talking about freedom that should roll off our tongues today.

How else to describe Jeff Bezos and his merry band of billionaire space travelers except as potentates who, as Debs put it, “wield greater power than crowned kings and despots”? How else to think of Amazon workers forced to submit to grueling work schedules but as “in no sense free” (Debs again)?

While the Socialist Party’s prescriptions need updating, they, too have much to recommend themselves. Workers would be freer to determine the course of their lives if we had shorter working hours, more democratic workplaces, a massive wealth tax, public control of investment and major industries, and guaranteed health care, education, housing, and childcare.

In the antiwar speech that eventually landed him in jail, Debs put it well: “Yes, a change is certainly needed, not merely a change of party but a change of system; a change from slavery to freedom and from despotism to democracy, wide as the world.”

Translation: If our desire is freedom, we need less Bezos — and more socialism.