Americans Are Starting to Love Unions Again

Labor union approval is now higher than at nearly any point in the last 50 years. The reasons: shit pay, teacher strikes, and Bernie Sanders.

Educators, parents, students, and supporters of the Los Angeles teachers strike gather in Grand Park on January 22, 2019 in downtown Los Angeles, California. (Scott Heins / Getty Images)

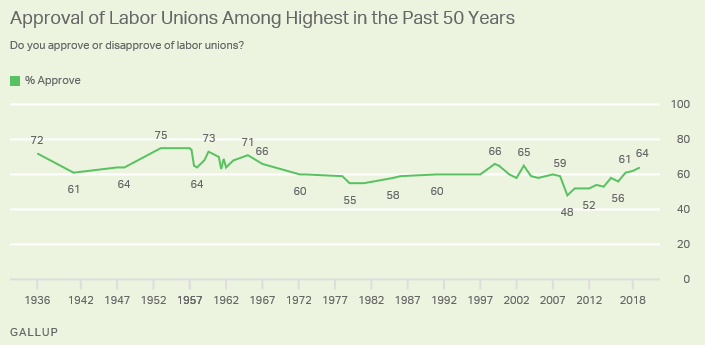

This Labor Day, we have cause to celebrate. Public support for unions has reached 64 percent in a recent Gallup poll.

Gallup has been asking the public about support for unions since 1936. Since 1967, the polling agency observes, the union approval rating “has only occasionally surpassed 60 percent. The current 64 percent reading is one of the highest union approval ratings Gallup has recorded over the past fifty years.”

To make sense of this trend, we need to take three factors into account: wage stagnation and benefits erosion, the teachers’ strike wave, and the rise of Bernie Sanders.

The first factor — substandard wages and benefits — only makes sense when you consider it alongside the other two. Wages are increasingly insufficient to cover skyrocketing living costs, and employers continue to slash benefits to increase profits, making life harder for working people. This is an obvious source of frustration with the status quo, a basic factor that causes working people to turn to collective action in the form of unions.

But worsening conditions don’t automatically juice unions’ approval rating, and they certainly don’t lead directly to increased union membership. On the contrary, wages have been stagnating since the seventies, and since then the union approval rating and union density itself have gone down, not up. Neoliberalism has been ascendant since the mid-seventies, and in that time its footsoldiers have been able to both wring more productivity and profit out of workers without sharing and also convince many workers that it’s the unions who are greedy.

So eroded conditions alone are not responsible for the uptick in the union approval rating. People don’t automatically warm to unions just because their employers are treating them poorly. They have to be presented with a credible alternative.

Enter the teachers’ strike wave, which started in 2018. The strikes in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Arizona, California, Washington, and several other states put unions in the news, making them visible and relevant to large segments of the population for the first time in decades. And importantly, by “bargaining for the common good” — or connecting their demands to the wellbeing of communities as a whole — the strikes were successful at impressing on people that what’s good for unions and workers is also good for students, parents, and the entire public.

But there’s still a missing piece of the puzzle. When the Chicago teachers went on strike in 2012, for example, the mainstream media gave them a chilly reception. This owes to the tenor of the broader conversation about public schools and unions, shaped by privatizers and union-busters in the education reform movement. For example, in 2008 Time Magazine published an issue with a photo of union-buster Michelle Rhee on the cover, hyping her heroic “battle against bad teachers.” And in 2014 the cover of Time read, “Rotten Apples: It’s nearly impossible to fire a bad teacher. Some tech millionaires have found a way to change that.” The story talked about the “war on teacher tenure” like that was a good thing.

Since then, public opinion about teachers and their unions has done an about-face. When teachers began striking en masse in 2018, they received largely sympathetic media coverage and overwhelming public support. At the height of the teachers’ strike wave, Time’s cover sported a portrait of a teacher overlayed with the words, “I have a master’s degree, 16 years of experience, work two extra jobs, and donate plasma to pay the bills. I’m a teacher in America.” That was one of three special covers for that issue, each sympathetically profiling a particular public school teacher. The feature inside was titled, “13 Stories of Life on a Teacher’s Salary.”

Since then, public opinion about teachers and their unions has done an about-face. When teachers began striking en masse in 2018, they received largely sympathetic media coverage and overwhelming public support. At the height of the teachers’ strike wave, Time’s cover sported a portrait of a teacher overlayed with the words, “I have a master’s degree, 16 years of experience, work two extra jobs, and donate plasma to pay the bills. I’m a teacher in America.” That was one of three special covers for that issue, each sympathetically profiling a particular public school teacher. The feature inside was titled, “13 Stories of Life on a Teacher’s Salary.”

Suddenly, it seemed, teachers and teachers’ unions were no longer considered the problem with public education. In fact, empowering them could be the solution.

What changed between 2014 and 2018? We’d be remiss if we ignored the fact that right in the middle of that period, the most pro-union presidential candidate in Democratic Party history ran for president. Bernie Sanders used the massive platform the race guaranteed him to criticize inequality and extol the virtues of unions and collective worker action. Even after he lost the primary, he spent the next several years spreading the same pro-worker, pro-union message, including elevating unions’ demands and materially assisting them in their fights against the boss.

Sanders has pulled American politics to the Left and created a much more pro-worker political climate on the whole. It was in this new climate that the teachers began to strike — as Eric Blanc points out in his book Red State Revolt, teachers in West Virginia and across the country were emboldened to take action by the unexpected success of Sanders’ message. And it was in this new climate that their strikes were greeted favorably by both the press and the public.

There are no guarantees that this spike in the union approval rating is permanent. But in anatomizing the bump, we can see what kind of work needs to be done to turn the trend into something more lasting.

Unions should continue to make themselves visible to the broader public through strikes and seek to foreground class-wide demands that benefit entire communities. Socialists should continue to use electoral politics to agitate against corporations and on behalf of workers and unions, on as big a stage as possible. If enough effort is put into these projects, it’s conceivable that this spike will only mark the beginning of a labor movement resurgence, creating a populace vastly more friendly to unions — and ultimately more likely to join them.