Nothing Ventured, Nothing Gained

Class struggle and running for office often pull in opposite directions. But we can’t build a socialist politics without navigating those waters.

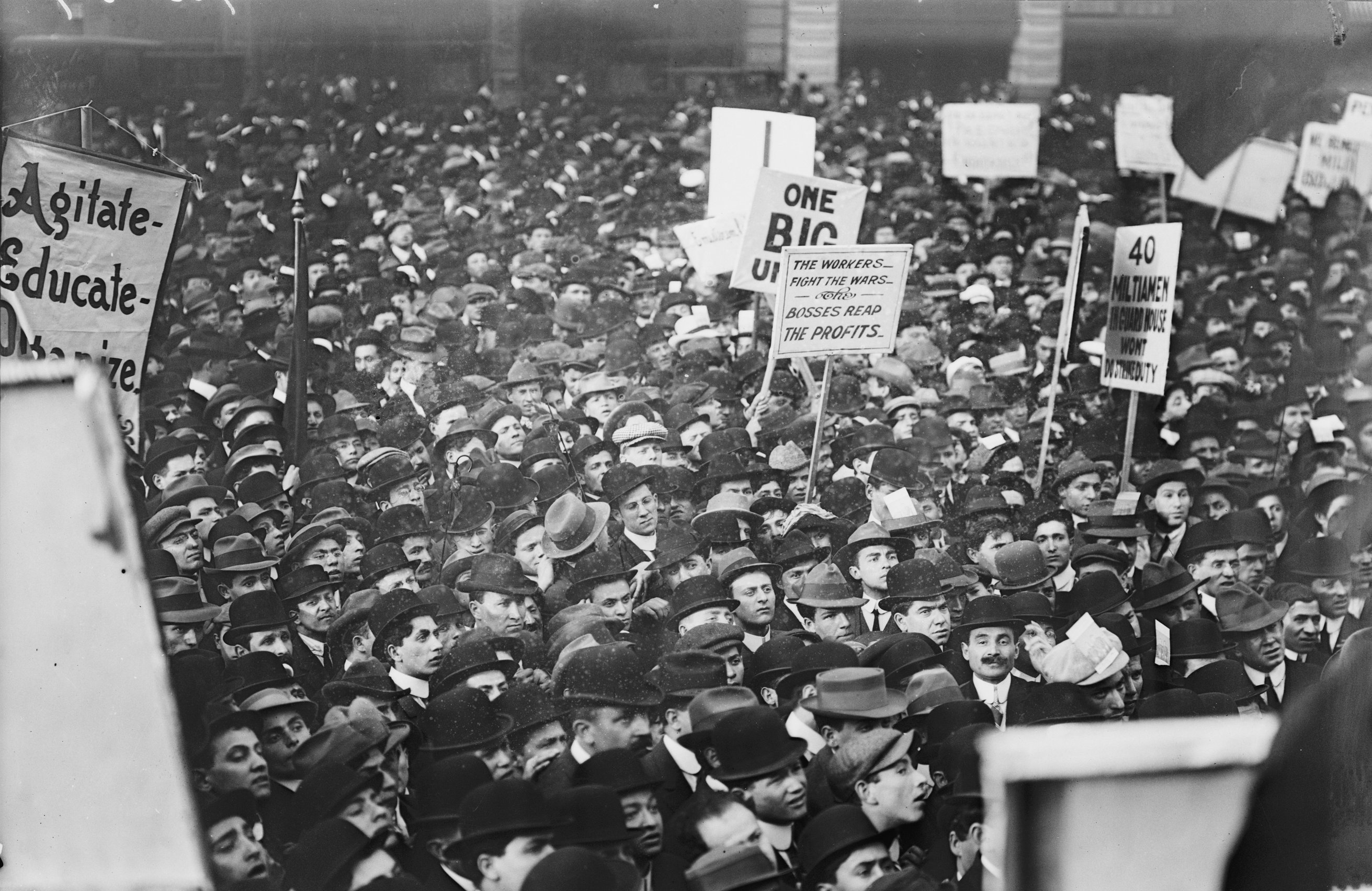

Socialists in Union Square, NYC, May 1912. Library of Congress / Flickr

Our Road to Power” explored the relevance of the Bolshevik experience for left organizing today. Charlie Post’s rejoinder to it offers a welcome opportunity to clarify its main claims and to develop them. Much of Post’s essay agrees with and repeats what was in mine. But some of it is tendentious, representing claims that aren’t implied in “Our Road to Power,” much less advocated.

Two structuring conditions confront the Left today, and both differ from the situation a hundred years ago. The first is that the Second and Third Internationals were operating in an era of state breakdown — what we might call a “revolutionary era.” Across much of the capitalist world, this opened up possibilities for socialist parties to attempt a capture of power. This effort was only successful because of the Left’s deep roots in the working class and its ability to mobilize it to deepen the political crisis and displace traditional power centers.

The socialist left today is lacking both of these conditions. Across the advanced capitalist world, the ruling class is completely unified, the state is stable, and there is no structural political crisis. There is deep disenchantment with neoliberalism, and this is what has allowed the astounding success of Sanders and Corbyn. But it is impossible to take this as a political crisis.

Second — and this was the real crux of my article — the Left is not only utterly isolated from labor, but has morphed into a formation that isn’t much bothered by that fact. It is mostly located in universities and its social base is urban professionals, not wage laborers. In the United States, it is minuscule in size and its main challenge is not to marshal its forces and avoid co-optation, but to grow to a size where co-optation might even matter.

If there is any way out of this impasse, I argued, it will be by taking reality as it is. First, it seems clear that the Bolshevik strategy of a frontal assault on the state is not on the agenda. This means that political strategy will have to be different from theirs, even while the goals are the same. Second, I suggested that whatever political organizations the Left generates to revive itself will most likely have to build on the Second International’s model of mass cadre-based organizations.

Whatever their failings, nothing else has come even remotely close to being as effective. And lastly, the Left needs to come back to class struggle as the focus of its politics — it has to base itself in the working class the way that both the Bolsheviks and the first generation of social-democratic parties did. No matter what the strategic orientation — revolutionary or aggregative — the prospects for significant political gains will depend on an organized and mobilized labor movement.

And what will be the strategic orientation of this revived left? In my view, the first ingredient is to build its class base, which is the indispensable foundation for anything else it might pursue. But this will have to be combined with an electoral component, so that we might use the levers of state power to both weaken the structural power of capital and further enable organizational capacities of labor. But this comes with a challenge. Left-wing social democrats had a similar ambition in the interwar and early postwar years. But the pressures of managing a capitalist economy and winning votes wound up overwhelming their socialist ambitions, and by the 1980s social-democratic parties were on their way to becoming centrist or even neoliberal organizations. If the Left is to successfully navigate the new course, it will have to find a way of avoiding this fate. And this is where I left it.

Post accepts much of what I have to say, and in order to advance the debate, it’s important to mark out the zones of agreement. First, and most importantly, he accepts that a ruptural break with capitalism is not on the agenda. It will be useful to clarify what this means. It does not suggest that a ruptures are now and forever impossible. For something to not be “on the agenda” means that it is not a realistic possibility in the short to middle run. It could become a live issue down the road, and indeed, I agree with Post that if socialism is to ever be achieved, it will require a final break, probably with a political upsurge of some kind. But political strategy has to be geared toward the world as we find it, and for the foreseeable future, such developments are not in the cards. To his credit, Post accepts this and gears his argument to its consequences.

Second, he also agrees that any chance for Left advance depends on returning to its roots in the working class. Indeed, Post has been arguing in favor of this for many years, so it is no surprise that he amplifies it here. And third, he also agrees that the best political vehicle for it is still the mass cadre-based party developed by the Second International — though modified to the best of our ability to minimize its negative tendencies.

His worries are concentrated on one point — my recommendation to combine electoral politics with class struggle. But on this issue, Post’s argument becomes rather obscure. The crux of his rebuttal is to point to the dangers entailed in running for political office and then managing the responsibilities of power within capitalism. Now, if he embedded that argument in a wholesale rejection of electoral politics, it would be a clear and lucid (if sectarian) point of view. But to his credit, Post seem to agree that any viable left will have an electoral wing as part of its political strategy. He agrees that fighting for reforms is essential to a socialist movement, and to consign the Left to forever pressuring the state from without is to stack all the odds against it.

But then, if we are to engage electoral politics, while building a base within workplaces and neighborhoods, as Post seems to agree, this amounts to nothing other than what I recommend — to move forward by combining class struggle with an electoral wing. Once he agrees with this basic point, it seems to me that the circle is closed and there is no deep strategic difference between us. The task now becomes how to navigate its challenges.

Post seems to be aware of this basic convergence, but because of his anxiety to differentiate himself from me, he begins to stretch things, bending my argument to suit his purposes. He points to the obvious fact that electoralism and class organizing sometimes come into conflict with each other and argues that when they do, the Left has to choose the side of class organizing. But he insinuates that my view somehow militates against this outlook, so that I’d recommend sacrificing class organizing for more votes, or that I am neutral about it. Perhaps he infers that since I argue for combining the two, I’m indifferent as to which one matters more. He has me saying that the Left ought to give “equal weight” to them. But I never say that and for Post to suggest otherwise is surprising.

First of all, to argue that the Left should combine two approaches, says nothing about their mutual relation. Now, I can imagine the reader asking for more clarity on what I might mean, if I had left the argument at that bland formula and said nothing else in the paper. But I said a great deal more — my argument was that the source of the Bolsheviks’ strength as well as the social-democratic parties’ success was their reliance on class power. The whole point of the essay, after all, was to urge the Left to implant itself again in labor so that it might gather up its power.

Relatedly, Post reminds us that when reforms have been passed, it has required massive, quasi-revolutionary political mobilizations. Again, I not only agree, but made that point in my paper. The implication is that my strategy runs up against this somehow. But how, exactly? It only does so if I am construed as a traditional social democrat, maybe a shill for the Democrats, advising people to vote and then go home. But this would wildly distort what I said, since my point was to argue for building the kind of power that might enable the mobilized power that Post correctly sees as the condition for reforms.

In sum, readers might legitimately ask what the big deal is here. The points Post raises are most welcome, but they are also entirely consistent with my argument. They amount to a fair warning that things might go wrong, that class struggle and state office often pull in opposite directions. That is true, of course. And if Post had recommended that we reject state office altogether, or reject electoralism, then there would be a real disagreement. But to his credit, he eschews the sectarian route. The fact is that, across the world, there is simply no question about whether or not socialists should have an electoral dimension as part of their strategy. The only debate is over how to manage it in combination with class organizing

The odds are, of course, stacked against us. The attempts so far to combine class struggle and electoral efforts as a strategy for socialism have failed. But what is the other option? The Left has to confront the world as it is, not as we’d like it to be. If Post and I are right that, in the middle run, a ruptural break with capitalism is off the agenda, then this strategy is the only game in town. It has its risks, of course. But try finding a strategy that doesn’t.