How Wallace Shawn Found His Voice

An interview with the actor, playwright, and socialist Wallace Shawn.

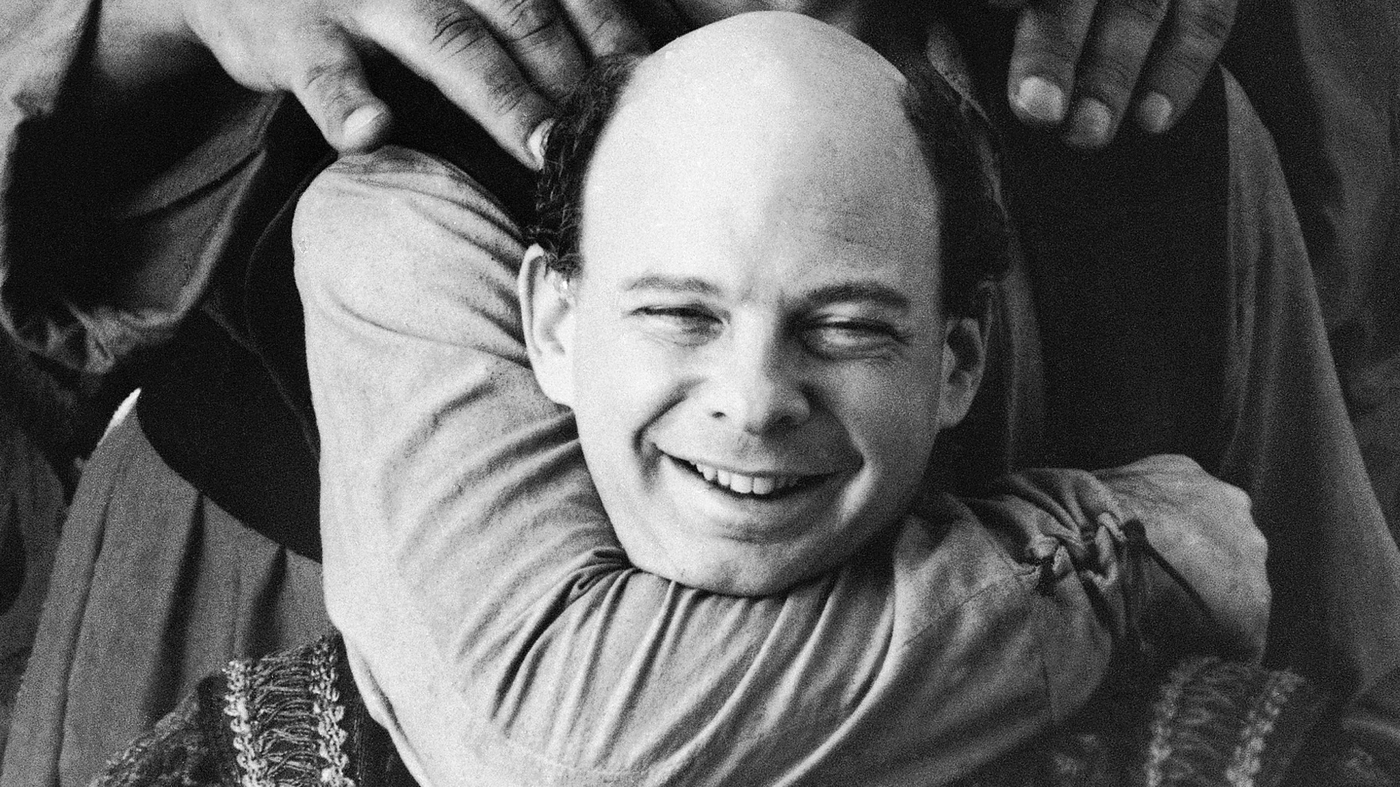

Still from The Princess Bride.

- Interview by

- Jason Farbman

On first sight Wallace Shawn’s face will transport you. If you have watched movies or television in the last forty years, there is a cultural milestone, which you love deeply, in which Shawn has played an unforgettable role. Depending on your age, that will be Gossip Girl, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Clueless, The Princess Bride, or My Dinner with Andre, which he also wrote. On the street, children who hear him speak instantly register the voice of Toy Story‘s Rex the Dinosaur.

Shawn is also a playwright, whose work has consistently pushed past the comfort levels of the comfortable and wealthy to expose their complicity as society degrades. Only months into the Trump administration, two of his older works on life under totalitarian states have received new stagings — Evening at the Talk House in New York, and The Designated Mourner in Los Angeles. Each has garnered far more press attention today than when they were first staged under Democratic administrations (Obama in 2015 and Clinton’s in 1996, respectively).

In addition to plays, Shawn is an essayist who has just published his second book, Night Thoughts, which explores capitalism, extremism, revolution, and punishment, among other themes. He’s an open socialist, who has participated in early efforts to free Chelsea Manning, been a vocal supporter of Palestinians, and sits on the advisory board of Jewish Voice for Peace.

Jacobin’s Jason Farbman spoke with Wallace Shawn about the role art and artists can — and can’t — play in building political movements, and how a famous actor became an open socialist.

Night Thoughts

In Night Thoughts you’re very clear that humanity desperately needs an entirely different social system. In what seems to be a recurring theme for you, you spend some time discussing the tragically untapped potential of so many people.

The most overlooked fact about the world is that all the people we see when we walk around every day, or when we turn on the television, were not inevitably destined to be the way they are today. We take it for granted that, however they are, they were born that way, and could never have been any different. We encounter people who seem terribly limited in different ways, and we think “Oh, that’s too bad,” but given a different social system, they wouldn’t have been that way.

You might say, “Not every baby is born with the potential to be a genius like Noam Chomsky.” I don’t know if that’s true or not. But certainly everybody we see could have been very, very different from what they are, and more than what they are.

The brutal reality is that privileged people see people who were born without privilege, people who didn’t have a privileged upbringing and education, as belonging essentially to a different species. To be frank about it, privileged people view the majority of the people they see and meet, the not-privileged, as creatures born with a lower degree of intelligence than themselves, because the un-privileged speak differently, dress differently, consume different cultural products, et cetera.

Privileged people assume that the less-privileged are less privileged precisely because they were born with a lower degree of intelligence. That’s their unconscious sociological analysis. Even those privileged people who have thought about it and who know that that isn’t true are unable to retain that awareness on a daily basis. It’s not something they have time to think about. Privileged people think, “I was born intelligent. That’s why I’m a lawyer or a playwright. The guy making my sandwich was born less intelligent. That’s why he’s making sandwiches or dealing drugs and being thrown in prison.”

Night Thoughts is a book about capitalism, class, and revolution. And yet you don’t once use the words “worker” or “capitalist.” It reminded me of your earlier essay, “Why I Call Myself a Socialist,” which does not feature a single use of the words “capitalism” or “socialist.” And yet these are two profoundly affecting pieces about the lives and opportunities and talents denied to so many people under capitalism.

Well, you have to ask, what is a writer? To me, the social role of a writer is partly to try to avoid carelessness and laziness in the way we use words, because we live in a world of great intellectual confusion. People bully and manipulate each other by using language very vaguely and trying in effect to trick people into agreeing with them. So to me, writers should try to be very sure that both their readers and they themselves truly understand what they’re saying. For me, it helps to use simple words, to try to avoid clichés, and to stay away from words and phrases whose meanings are disputed or unclear. It’s not helpful to use undefined phrases that could mean many different things. Most people don’t know what the word “capitalism” means. And among those who do, the definition is disputed.

I think if I have a talent, it probably lies in explaining certain things to people who don’t already think them. I don’t think it’s impossible that I could say some things that would nudge someone — at any rate, someone who is something like the way I used to be — in the direction of where I am today. So I don’t want to start right off by alienating those people. I don’t want to use phrases that might make people feel, “Well, he’s a member of a special club that I don’t belong to.”

It’s also not how I talk. I’m trying to speak in my own voice. Night Thoughts is very short because it contains everything I think, everything that I believe I can express clearly and that I think I’m right about. If there were more things, they’d probably be in the book and maybe it would be 650 pages long.

You instead use the words “the lucky” and “the unlucky.”

To say “lucky” and “unlucky” is quite an accurate description of the people of the world. It’s also not using words that identify me with a particular sect. Sure, I’m a leftist, and I could use leftist words. But why should I? I also come from a Jewish background. I could pepper my writing with Yiddish expressions, but it’s not my style. If you do that too much you’re saying, “This is written for a certain group of people, by one of them.”

Throughout the book, you are making structural arguments, and about people being compelled in certain directions. It was interesting to me how you traced this line of thinking to a discussion of punishment, about what to do with capitalists after the revolution.

Why are you thinking about what to do with the rich after the revolution?

Well, I believe in radical change. I don’t think the rich should rule the world, as they do now. But if a different system should replace the current one, the character of the new system will be determined to an important degree by how it treats those over whom it would then have power, the former rulers. I don’t believe in revenge or even really in punishment, and I think that people who take revenge against formerly powerful monsters become at that moment powerful monsters themselves. Of course I’m a member of the bourgeoisie, and so are most of the people I know and love, so you might suspect my motives when I say these things. You could say I’m trying to protect the asses of the bourgeoisie, and my own ass is one of the ones I’m protecting. But I can’t deny my own beliefs simply because someone might suspect my motives. Those are my beliefs.

I don’t believe in punishing the poor. And I don’t believe in punishing the rich, either. I don’t believe in punishing the innocent. And I don’t really believe in punishing the guilty. I realize that leaves a lot of questions on the table that I don’t resolve in the book. For instance, what do we do with serial killers, who are driven to commit murder again and again? There must be some way we can cope with those people. We don’t want them to kill everyone.

Punishment of some kind is a very articulate way for society to express its disapproval of certain actions. There should be some way that society can express its disapproval of what was done. But I don’t really believe in punishment, because I think it’s based on an erroneous idea of how people make decisions. Person A decides to murder Person B. Well, a lot of forces go into what we call “a decision,” and a lot of those forces are unconscious and not under the control of the person making the decision. Blaming the murderer assumes that he could have behaved differently. It’s hard to prove that.

You discuss a revolution that can upend capitalism, globally. It’s a task so enormous it can be impossible to imagine: conquering the greatest military powers the world has ever seen; taking control of the running of society; and the organization of working people across the world to cooperate in these tasks. These more practical aspects are what most consume the attentions of people on the left. Where does culture fit into all of this?

We need emotional depth and sensitivity. Particularly if you’re imagining, as I do in the book, “What if the Left succeeds?” Let’s be frank. Sometimes people with wonderful motivations have disappointed everyone when they came into power, because of a lack of emotional depth and sensitivity and compassion. Just to overcome global warming alone requires brains! To try to guide society, that requires emotional depth and sensitivity.

People need the wisdom, or the imagination, of others. Who do you learn from? You might have a wise and compassionate friend. But very few people, maybe no people, can invent their own menu of possibilities. Don’t great works of art have something to teach you? Maybe Tolstoy has something to teach you. Maybe Debussy. Maybe many others. No one would deny that Noam Chomsky has special intellectual capacities. Beethoven has special capacities, Ibsen had great insight into the psychology of human beings. If we’re imagining that a better world could be created, don’t we need their help?

We were talking about the neglect of higher culture. Then there’s the way the Left understands mass culture, which can be brainless or even have terrible political conclusions. But millions of people see it, the entertainment industry makes millions and millions of dollars. Quite a few people draw pessimistic conclusions from this, about what that says about people. As if that’s just sort of a static fact about people, that Hollywood is giving them what they already want. What do you think about the popularity of mass culture?

I grew up on a book called the Blue Fairy Book by Andrew Lang, which was a collection of fairy tales written by nineteenth century writers. These were folk tales that were told and passed on and then transcribed and re-imagined by some rather sophisticated storytellers.

Yes, I have participated in the creation of some very popular, commercial works, quite a few of which contain fairy tale or folk tale elements. But from my point of view, most American storytelling films are quite reduced — less refined, less complicated, and less profound than the fairy tales I grew up on. If people had been exposed to the earlier versions, they would have understood and loved them, but most people have not been exposed to the earlier versions.

A diet of sugar can addict you to sugar. You can become addicted to chicken fingers to the point that you would reject a delicious plate of pasta in favor of chicken fingers, but if you were to overcome the addiction, you would actually enjoy the pasta more than you ever enjoyed the chicken fingers.

People have a great hunger for stories, for imaginative expression, for insight, so if there’s no way they can access Charles Dickens or Verdi or other very popular but slightly complicated artists, they’ll gorge themselves on things that aren’t really worthy of their attention. Do I think that makes people less smart? Yes, I do. And I definitely think that it makes you smarter to read a smart book or listen to a smart piece of music. I totally believe that.

It’s important to emphasize how little people have access to art that might provide more emotional depth and sensitivity. The movie industry repeatedly claims it isn’t to blame for what gets produced, because studios are just making films to satisfy people’s demand.

Well, that’s just not true. They do believe that, and there is short-term evidence for that. But this is very crude. Trump says “nobody is interested in seeing my tax forms, and the proof is that I won the election.” People in Hollywood would say, “the public’s favorite thing is to see people’s heads being blown up, and the proof is that my movie about people’s heads being blown up made five hundred million dollars.” That’s just not proof.

You’ve had a very successful career. Millions of people can easily recognize your face, your voice, your work. And you’re an open socialist. There are sections of the Left that criticize liberal celebrities who make statements, or who take roles deemed insufficiently radical. Is it fair to expect that celebrities ought to be militant leftists?

A good actor can present a believable imitation of a real person, so by definition a good actor has to have some kind of insight into people — and probably into society too, as a good actor can believably imitate how a person interacts with others. A good actor also has to be very intelligent, as good acting requires the actor to read a line in a script and grasp not only its full meaning but also its many implications and undercurrents — something that most people can’t do. So you’d think every good actor would be left-wing, but that’s not quite true. Many good actors do lean that way, many supported Bernie Sanders, for example, but Jon Voigt is a good actor, and he’s quite conservative. Psychological factors can cause intelligent and insightful people to cling to absurd beliefs.

As for very successful actors or so-called celebrities, well, success can make a person much less likely to see what’s going on in the real world than they were before. If you’re privileged, there’s a lot you need to not see, to deny. So I’m not shocked that all celebrities aren’t militant leftists.

Is there such a thing as left culture? Should there be?

It’s like dreaming at night. Dreams don’t tend to be left wing or right wing. They’re something else.

When I write plays, I don’t start with the intellect. I don’t think I could sit here and say, “I am vehemently opposed to capital punishment, and I am going to write a play to show why capital punishment is wrong.” For me, things that are interesting come out of my unconscious.

There’s also a limitation on what I can write, based on what I know. If I wrote about things I don’t know anything about, it would be lame. Could there be leftist art? There might be art that shows the suffering of humanity because the writer has seen that, and cares about that, and it comes out. I would be pretty reluctant to try to write a play about the suffering of workers in the garment industry in China — because I just can’t believe that the product of my ignorance would be a profound play. If you have someone with deep left-wing convictions and an understanding of life, some of that could come out in their work. It might come out, or it might not. In principle, I’m not opposed to someone trying to create a work of art that makes a point. I don’t know how J. B. Priestley went about writing it, but I really liked the play “An Inspector Calls,” for example. But great works of art tend to surprise you, even shock you, and that probably means that the artist also has to be surprised. So that might be why it’s hard to write something great if you already know the point you’re going to make.

Why Wallace Shawn Became a Socialist

I’d like to turn to your specific biography, because it would be good to know what incidents informed your art — and your radicalization, particularly as someone from a well-off family.

In Night Thoughts you describe your childhood in some detail, especially the training you received to grow into an adult member of the ruling class.

My parents were not the 1 percent, and I am not the 1 percent. But let’s say the 10 percent. The complexities of my family’s class positions are quite interesting. My father’s father was a peddler and became prosperous. He was really a self-made man who went from having a junk wagon to having a very successful store. He ran away from home when he was fourteen or maybe younger. His wife, my grandmother, was barely literate and only went to school through the third grade. So my father grew up prosperous, but with parents who had been poor.

My mother’s mother grew up in a prosperous family, but then her husband died when she was in her early twenties. She became quite poor. My mother grew up poor, with a mother who had once been prosperous.

Then my father, rising up the ranks at the New Yorker, had a good salary. My parents were doing nicely. My mother always seemed to take it for granted that we were prosperous. As a boy I had a certain awareness of it, a certain feeling of shame about it. I remember a friend, who was poor, came to our home — a quite nice place on Fifth Avenue — and the friend commented on the intricate molding on the ceilings in our apartment. I had never even noticed it! It was an incredibly upsetting moment for me.

So politically, were your parents liberals?

Even through the late sixties, my father and mother were both classic FDR-loving Democrats. They had no comprehension of socialism, or anything outside the realm of the American system. They went from thinking the government wouldn’t lie to the public — that Lyndon Johnson couldn’t possibly be lying, because he was the president — to being militantly antiwar.

My father’s opposition to the Vietnam War really split the staff of the New Yorker. Once he was opposed to the war and believed the government was lying, he was open to other types of possibilities regarding what the US government might do. He published things that alienated large portions of the staff, many of whom were veterans of World War II, people like JD Salinger, who, having been soldiers themselves, were not happy at all at the thought of opposing what the American soldiers were doing.

Your father ran the New Yorker for decades — to stay on top of a magazine like that, in such a competitive publishing world, for so long, doesn’t seem like a particularly happy model from which to work.

I don’t think my father would’ve said he achieved a great deal of happiness. He wanted to be a writer. But he was trapped in the Depression. My mother got him a job at the New Yorker. He was a socially awkward and sensitive person, who perhaps could never have gotten a job on his own. But my mother had been a successful journalist in Chicago, where they both grew up, and she got him a job at the New Yorker, as a reporter. She got the job for herself, and then said, “Would you mind if my husband helps me?” They said, “Why not?”

She eventually left, but he stayed. He only had one job in his life — from 1933 to 1987. I think, in those later decades, he felt very trapped in his job. He was, perhaps tragically, very identified with the institution of the New Yorker. He wanted to give it a future that was in keeping with what it was like at the time, an impossible aspiration really.

When I showed interest in being a writer myself, he was very into the idea that I not be trapped in a job.

A lot of your writing is quite conversational, quintessentially, My Dinner with André. It seems that as your characters work out their thoughts, the audience is invited to do so as well. And over time, your works seem to have become increasingly more political. What was your own process of working out your ideas about the world? How did someone — whose chief responsibility was to make himself happy — become an anticapitalist?

I was not as radical as my own father until I was about forty. I was more of a centrist than he was, in a way. In 1974, my father published a piece that influenced me, by Richard Goodwin, who had worked for President Kennedy. He adapted Marx for the conditions of the United States in the mid-1970s. This was a stretch for my father, who for all his life believed America was basically a good nation, but we just kept making these terrible mistakes. He thought if you voted the right people into office, then everything would be great. Goodwin’s piece was about the structural reasons why there were problems in America.

I missed the sixties. It happened, but I wasn’t there. I began to change just after I’d turned forty, when I went through a crisis. I realized that I, myself, was involved in the way the world was. That my role was not as an observer, as I had thought for the first forty years of my life. I wasn’t in the audience, I was in the drama. And I was one of the beneficiaries of what I already knew to be imperial behavior on the part of my country. Once I realized that I was in the drama, I started reading more about the things that the United States had done. I haven’t read many books in my life, partly because I read very slowly, but I’m proud to say I have read volume one of Capital by Karl Marx, all the way through.

My girlfriend [writer Deborah Eisenberg], had always been a leftist by temperament. She didn’t impose her beliefs on her boyfriend or anyone else. But we did have some discussions, when we first met in the early 1970s, in which she propounded radical ideas that shocked me. One of them is captured in Night Thoughts, where she raises the possibility that civilization might on the whole have been a bad thing. She’d been a student of anthropology and had thought about a lot of things that had never crossed my mind.

Your radicalization came during a rather unlikely period. Socialism was not at all popular in the Reagan/Thatcher 1980s, and when the Soviet Union collapsed it was extremely rare to find anyone who thought there could be any alternative to capitalism. At the same time as alternatives to capitalism were taken off the table for a generation, you found socialism.

This was in a period when I had fallen, by chance, into becoming an actor, and had become rather successful as an amusing character actor. I had received some rather large checks, and had gone from being someone with no prospects, an avant garde playwright with no plan for making a living, to suddenly becoming someone who was getting these big checks. I was paid much, much better than I am today.

Someone coming from my background has to struggle not to succeed, in one field or another. Throughout the mid-1980s I was doing quite nicely, so it was brought home to me, and quite vividly, that I was a beneficiary of the world’s status quo. If I went into a restaurant and saw people of my own class, I would feel such hatred for those people I would feel ill. And every time I’d get sick I’d realize that I was just like them. I felt a loathing for myself as someone responsible for the suffering of humanity. I thought, “The United States is the enemy of humanity, and I’m one of the people they’re doing this for.”

And then you traveled to Latin America in a volatile period — the late 1980s — to see the Sandanista revolution.

I wanted to go to Nicaragua, to see if there could be a different way of organizing society that would be better. I had always been an incredible physical coward — and I would say I am one again now. But at the time I was in such a state, because I had come to hate myself. We were told, “You can’t just go to Nicaragua, you have to go to El Salvador and Honduras to see what Nicaragua used to be like, and what the differences are.” I was very motivated, and I rather aggressively collected phone numbers of people in Central America whom we could meet. We also went to Guatemala, three times. That all fed into my point of view becoming really different from the point of view of a lot of my friends.

You mentioned the disgust you would feel, walking into restaurants full of the luckier people in the world. Given this animosity, it’s interesting that same group seems to be the main audience for your plays.

For initial performances of The Fever, for instance, you would go perform in the living rooms of wealthy friends, performing directly for and in front of the lucky ones — forcing a sense of inculcation in the guilt of your character. Your movies have had enormous and broad appeal, but your plays seem targeted at the wealthy. Why is that?

I fell into theater because I’m attracted to it — I have that weird theater gene, and I was always fond of theater. There was a period where nobody would produce any of my plays, but then when people started doing them I realized the audience was very unfriendly. At that time I didn’t have any kind of class analysis of it. By the mid eighties when I finished Aunt Dan and Lemon, I realized more clearly that theater has a more middle-class audience. It’s not like the movie audience, where anyone can go.

I started trying to make the audience part of the play. In Aunt Dan and Lemon I presented some right-wing and even fascistic points of view, and left it up to the audience how they were going to react to them. There’s a vaguely liberal character in the play, who is obliterated by the conservative and openly-fascistic characters.

I intended to get a response from the audience, and in that way they become part of the play. With any play the audience is making its mind up about the characters, but there is a bigger space for the audience in some of my plays. If they don’t think about what they’re seeing and try to come to their own point of view about it, there’s no play. The drama takes place in the individual minds of the audience. That’s the battlefield.

As I wrote my later plays, I began to realize I was speaking directly to the bourgeoisie. That’s who comes to plays. So I’m going to talk to them. And I know them, because I am one of them. So The Fever is like a secret meeting of the bourgeoisie, in which one member is talking to the other members. But I can’t go on the assumption that the people who go to my plays know less than I do. If I felt that way about my audience, I’d become too depressed. I assume they’re like me, and then I try to present things I myself will find unexpected and unforeseen — things I hadn’t thought of before. Many of my plays are meant to be upsetting, and if I don’t feel upset by them as I’m working on them, I realize they’re not finished yet.